![]()

MARKET EXPANSION, STATE CENTRALIZATION, AND NEO-CONFUCIANISM IN QING CHINA

The stereotypical image of imperial China, as theorized by Marx, Weber, and Wittfogel, is of a stagnant agrarian empire governed by an inward-looking, despotic regime. This conception has long been rejected. Mark Elvin and others found that in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, China experienced a golden age of vital commercial expansion and growth of maritime trade (Abu-Lughod 1989, 316–340; Braudel 1992, 32; Elvin 1973; Ma 1971; Shiba 1970, 1983). These trends abruptly stopped in the early fifteenth century, when the Zheng He expeditions ended and the capital city of the Ming empire (1368–1644) moved from Nanjing, in the southern coastal area, north to Beijing. After this inward turn, according to this literature, China became isolated from the world and was caught in a “high-level equilibrium trap” not broken until the nineteenth century (Elvin 1973; Wallerstein 1974, 53–63). This revisionist image of China does not stray much from the traditional view as far as the four centuries between Ming’s retreat from the sea and the Opium War (1839–1842) are concerned. It does not dispute the idea that late imperial China (c. 1600–1911) was a backward, agrarian empire. Nor does it reject the idea that China differed fundamentally from the commercializing and rationalizing early modern Europe until the nineteenth-century “impact of the West,” which injected a new dynamism into China from without.

A wave of more recent research challenges this view, showing that after c. 1600, China witnessed a renaissance of maritime trade and internal commerce. During this period, China’s level of commerce was at least as high as Europe’s. China also experienced an impressive and continuous increase in agricultural productivity, per capita caloric intake, and life expectancy (Flynn and Giraldez 1995; Frank 1998; Goldstone 2000, 2002; Hung 2008; Lavely and Wong 1998; Lee and Wang 1999; Pomeranz 2000; Wong 1997). During the same period, China witnessed a rationalization and centralization of the state not unlike many contemporaneous European states (Faure 2007; Huang 1996; Marsh 2000; Rawski 2004).

The parallel commercialization and state centralization in China and Europe is not surprising, as they both resulted from the surge in the world’s silver supply following the European discovery of the Americas. The silver that the European traders brought back to Europe fueled an inflationary commercial expansion in the sixteenth century and formed the revenue foundation for state builders to construct centralized administrative apparatuses. European traders also brought silver to other parts of Eurasia in exchange for large quantities of textiles, spices, tea, ceramics, and other goods. This generated the same thrust of commercialization and state centralization in many Asian societies. Some even estimate that the quantity of American silver that ended up in China was in fact larger than the amount ending up in Europe throughout early modern times (Frank 1998, 131–164).

MARKET EXPANSION IN THE “LONG EIGHTEENTH CENTURY”

The massive flow of silver into China began in the mid-sixteenth century and generated pockets of prosperous markets and handicraft production centers in the eastern and southeastern coastal areas. The political chaos of the closing decades of the Ming dynasty and the turbulent dynastic transition of the mid-seventeenth century, however, constricted the expansion of commercial prosperity to other parts of China. A thriving empirewide market economy did not come into being until the eighteenth century, when the new rulers of the Qing reestablished the empire’s stability and unity.

After c. 1500, the Ming’s regime capacity decayed rapidly as government corruption grew, intraelite struggles intensified, and budget deficits mounted. Demographic pressure, hyperinflation of the paper currency issued by the state, and the growing power of the local tax-farmer-landlord-moneylender class pushed the peasants to the brink of bankruptcy and starvation. In the meantime, the balance of power between the Ming and neighboring semi-nomadic tribes to the north was disrupted by the expansion of the Jurchens, who turned to agriculture, incorporated other tribes, and transformed a tribal confederation into an empire of Manchus. On the southeastern coast of China, illicit trade conducted by armed Chinese and Japanese traders flourished, challenging the government sea ban (Goldstone 1991, chap. 4; Huang 1969, 105–123; Tong 1991, 115–129; Wakeman 1985, chap. 1; Wills 1979, 210–211).

The state’s continuous attempts to solve the fiscal crisis by increasing land taxation only worsened the situation. It added to the peasants’ burden and in the late sixteenth century led to an explosive growth of social disturbances in the form of rampant banditry and tax revolts. Confronted with increasing unrest, the Ming government decided to reform state finance by exploiting the booming private trade. In the 1560s, it abandoned the crippled paper-currency system and shifted to a silver standard—which was possible only after the massive silver influx from overseas trade with Japan and Europe. Peasants’ corvée labor, one of the major causes of peasant hardship and unrest, was replaced by a standard silver tax. This reform put China onto a bimetallic monetary system. Small and daily transactions were conducted in copper cash, which was mostly produced in Chinese state-run mines, while bulk transactions and taxation were measured in silver. This monetary system remained intact until the late nineteenth century. Concurrent with this fiscal and monetary reform, the Ming state also lessened its restrictions on maritime trade and taxed licensed seafaring merchants (Atwell 1986, 1998; Flynn and Giraldez 1995; Huang 1969, 105–123; Quan 1996a; Wills 1979, 211). These policies immediately improved the state’s fiscal strength, and by the late sixteenth century, the empirewide turmoil had been substantially curbed.

This containment of the chaos, however, broke down at the turn of the seventeenth century. Financial difficulties incurred by the costly Sino-Japanese War in Korea in the 1590s, the outbreak of full-fledged warfare with the Manchus in the 1610s, rampant government corruption, the eruption of large-scale peasant wars in the northwestern and southwestern interior, and the interruption of silver inflow caused by the European “seventeenth-century crisis” and Japanese seclusion policy all caused a return of empirewide turmoil, which eventually led to the collapse of the Ming regime in 1644.

The Manchus shrewdly used this chaos to expand into China proper through military conquest. Within a decade after they took Beijing, in 1644, the Manchus had established control over most of China except part of Fujian province and Taiwan, which became the last bastion of Ming loyalists. The turbulent Ming-Qing transition interrupted China’s foreign trade and, thus, silver inflow, as the Manchu state evacuated all the coastal populations in the 1660s and 1670s in a desperate measure to isolate the remaining Taiwan-based Ming loyalists. The termination of silver inflow caused a deflationary economic crisis, known as the “Kangxi Depression,” during the first two decades of the Kangxi reign (1662–1722), rolling back the late Ming expansion of the market economy (Kishimoto-Nakayama 1984).

Following the collapse of the Ming loyalist regime in Taiwan, in 1683, as well as the lifting of the maritime-trade ban and the revocation of the coastal-evacuation policy, Chinese-European trade resumed. During the eighteenth century, the mounting European demand for Chinese products and the subsequent influx of American silver into China fuelled the commercialization of the Chinese economy far more ferociously than it had been during the late Ming period (Atwell 1986, 1998; Frank 1998, 108–111, 160–161; Hung 2001, 473–497; Quan 1996a; Naquin and Rawski 1987, 104; Rowe 1998, 177).

Contrary to the traditional “oriental despotism” thesis (Wittfogel 1957), which suggested that the imperial state in China was constantly hostile to private commerce, the Qing state was in fact very active in facilitating commercial growth. The Chinese state’s procommercial stance emerged in the late Ming period, as the growing commercial economy began to be recognized as an unalterable reality. Beginning in the late sixteenth century, the traditional Confucianist hostility toward silver, internal commerce, foreign trade, and merchants lost ground to the school of thought emphasizing the “natural law” of the market economy. This thinking proposed that the market economy would flourish under appropriate nurturing, not government control. This pragmatic attitude toward commerce continued to grow in the Qing bureaucracy and had become a mainstream position by the eighteenth century (Chao 1993, 40; Chen 1991b; Gao 2001; Lin 1991, 9, 13–17; Rowe 2001; von Glahn 1996, 215–216; Zheng 1994, 133–150). For example, the Qing government keenly promoted commerce by developing the empire’s commercial-transportation infrastructure and stimulating new production and marketing sectors by offering incentive packages and low-interest loans for entrepreneurs in targeted areas (Rowe 1998, 184–185).

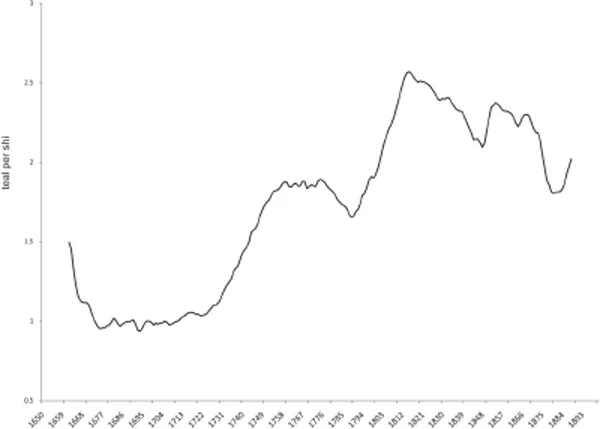

Accompanying the commercial expansion was long-term inflation starting in the 1680s, in which average grain prices increased three- or fourfold during the following century (Guo 1996; Quan 1996b, 1996c; Wang 1980, 1992). The inflation was generated by population expansion and continuous silver inflow.

This inflationary pressure during the eighteenth century was not distributed evenly, as it hit economically advanced regions the most. Comparing the price of rice in various regions across the empire in 1723–1735, Quan Hansheng (1996d) finds that the price level was highest in the Lower Yangzi Valley and the southeastern coast and lowest in the southwest, with the Mid-Yangzi region in between. The interregional price difference could be as much as 200 to 300 percent. This touched off extensive regional specialization and economic growth driven by Smithian dynamics.1 While the high-cost areas in the Lower Yangzi region (e.g., Jiangsu province) and on the southern/southeastern coast (e.g., Fujian and Guangdong provinces) witnessed rapid development of high-value-added production including nonfood cash-crop agriculture (mulberry trees for silkworm raising, cotton, and tea, for example) and handicraft manufacturing (such as ceramics and textiles), areas with lower inflationary pressure such as the Upper Yangzi region (e.g., Sichuan province), Mid-Yangzi region (e.g., Hunan province), and the empire’s southwest (e.g., Guangxi province) were transformed into peripheral zones that exported foodstuffs and other raw materials such as timber and fertilizer to more advanced regions.2

FIGURE 1.1 GRAIN PRICES IN THE LOWER YANGZI DELTA, 1650–1900 (TAELS PER SHI, TWENTY-FIVE-YEAR MOVING AVERAGE) (SOURCE: WANG 1992, 40–47)

Speaking of the formation of an integrated national market in eighteenth-century China, Li Bozhong remarks that “China had developed into three major economic zones before the nineteenth century: the advanced zone in eastern China, the developing zone in Central China and the underdeveloped zone in the West,” with “the Yangzi Delta as the core and with the other two zones as the hinterlands” (Li 1999, 14).3 The dynamics of the differentiation of China into economic zones with different levels of development is similar to the differentiation of the European economy into core, semiperipheral, and peripheral zones after the long sixteenth century, a consequence of the uneven distribution of inflationary pressures following the massive inflow of American bullion (Wallerstein 1974, 66–131).

The inflationary market expansion, however, came to a halt in the 1820s, when the skyrocketing opium trade initiated by the British, in conjunction with a reduction in the global silver supply, caused a hemorrhage of silver and a deflationary depression in the early part of the Daoguang reign (1820– 1850), known as the “Daoguang Depression” (Kishimoto-Nakayanma 1984; Lin 1991, 2006). The massive contraction of silver supply in the Chinese economy brought about huge increases in the price of silver measured in copper, the supply of which remained more or less constant. The depression hit peasant taxpayers hard, as they found it increasingly difficult to convert their copper cash, earned in daily sales of their goods, into silver taels for taxation. In the meantime, the value of land and other property, usually measured in silver, dropped precipitously. The Kangxi Depression and Daoguang Depression therefore marked the beginning and the end of the commercial prosperity of what is known as China’s “long eighteenth century,” between the 1680s and the 1820s (see Mann 1997).

CLASS AND STATE FORMATIONS

Besides commercial expansion, eighteenth-century China also witnessed mounting ecological pressure. Thanks to political and social stability after the late seventeenth century and the popularization of such New World crops as sweet potato and maize, which turned unproductive highlands into productive areas, the population of China tripled between the mid-seventeenth and mid-nineteenth centuries. The total acreage of cultivable land, however, only doubled during the same period (Ho 1959; Huang 2002; Naquin and Rawski 1987, 24–26; Wang 1973, 7). By the turn of the nineteenth century, the diminishing ecological resources vis-à-vis the expanding population had turned into a looming ecological crisis (Elvin 1998; Marks 1996, 1998).

The eighteenth-century expansion of commerce and population brought forth drastic social change. The predominantly manorial order gave way to a peasant economy in the countryside. Although this transition had already begun in the Ming dynasty (Elvin 1973, 235–267), a substantial portion of the agrarian economy was still dominated by large estates in early Qing, especially in North China, where large amounts of land had been confiscated by Manchu bannermen and noblemen as estates (Myers and Wang 2002, 612). When the population of indentured laborers, such as tenant-serfs (tianpu) and bondservants (nupu), expanded alongside the rest of the population, estate owners began to eliminate the increasing burden of feeding their workers by partitioning their estates into small lots and selling or renting them out. In the expanding peasant economy, landowners came to rely on themselves, tenants, or hired laborers to work their land. Commercialization of land ownership polarized the peasantry into labor-employing rich peasants and labor-selling poor peasants (Huang 1985, 85–96; Rowe 2002, 493–502). The noblemen–indentured laborer stratification grounded on hereditary status was henceforth replaced by a landlord–tenant–hired laborer stratification based on contractual relations and alienable ownership of land and labor. The trend was exacerbated by the deliberate efforts of the Qing government to emancipate indentured labor in the 1720s and 1730s. This transition was reflected in the revised Qing legal code and changing legal practices in the late eighteenth century, when landlords, tenants, and agrarian laborers began to be treated as commoners with equal status (Buoye 2000; Huang 1985, 97–105; Rowe 2002, 493–502).

While hereditary hierarchy was in decline, the somewhat meritocratic gentry elite remained a dominant sociopolitical force. In Qing China, as in previous dynasties, the imperial examination offered a way for the offspring of many wealthy landowning families, who could afford expensive education, to attain imperial degrees, which gave them gentry or literati status. The gentry class was internally stratified according to the level of degree, with the holder of the metropolitan degree (who passed the capital examination) at the top of the hierarchy and the licentiate (who passed the regular county examination that qualified them for higher-level examinations) and disqualified licentiate (licentiates who failed to renew their status through the county examination) at the bottom.

While some gentry elite succeeded in higher-level examinations and entered the bureaucracy to serve as scholar-officials at different administrative levels, the majority of lower degree holders stayed in their home areas and served as informal leaders, helping local governments explain and enforce their policies and local residents articulate their demands and grievances to the government (Brook 1990; Chang 1959, 1962; Elman 2002, 424; Jing 1982, 163–164; Rowe 1990, 1992; Rawski 1979, 54–80). With the intensive commercialization of the economy, mercantile activities became another legitimate and popular means for commoners to earn their initial wealth, which in turn enabled them to invest in their offspring’s education, in the pursuit of gentry status (Chang 1959; Hung 2008; Rowe 1992).

The standardized curriculum for the imperial examination, strictly controlled by the state, created a gentry class with a uniform ideological outlook. Participation in prefecture, provincial, and capital examinations also allowed the gentry elite to develop social networks extending beyond their hometowns and sometimes covering the whole empire (Elman 2000, 2002; Man-Cheong 2004). The gentry status, grounded on educational credentials, together with lineage ties became the glue that bound the mercantile, landlord, and state elites into intermeshing social networks.

At the lower end of society, a large portion of the peasantry experienced downward mobility as a result of commercialization and population expansion. As the per capita acreage of cultivable land decreased, poor peasants working on small plots of land were increasingly exposed to the risk of bankruptcy during bad harvests, forcing them to sell their land for food. In the early eighteenth century, the growing population of landless peasants was effectively absorbed by such agrarian frontiers as Sichuan and Taiwan (Entenmann 1982; Shepherd 1993). However, by the mid-eighteenth century, most of the fertile lands of the frontier had filled up. The landless migrants were left with the choice of settling in the infertile highlands or participating in nonagrarian sectors as peddlers, miners, or boatmen on commercial ships. Some became vagrants, moving from place to place to beg for food and jobs. Others became outlaws, who made a living through illegal activities such as smuggling, private coinage, and banditry (Jones and Kuhn 1978; Kuhn 1970, 39; Leong 1997; Rowe 2002, 493–494). This marginal population was vulnerable to the vicissitudes of nature and market and to abuses by local officials. They were excluded from the safety net of lineage organizations and were beyond the reach of the imperial public order grounded on baojia, the village-based mutual monitoring system.

Synchronic with the rise of absolutist states in northwestern Europe in the late seventeenth and ...