![]()

Part One

THE FILM-MAKER’S CRAFT

![]()

1

NATIONAL STYLES IN CINEMA

‘LOOK AT THE flowers,’ said Jean Renoir one day while on a search for suitable locales in a suburb of Calcutta for his film The River. ‘Look at the flowers,’ he said. ‘They are very beautiful. But you get flowers in America too. Poinsettias? They grow wild in California, in my own garden. But look at the clump of bananas, and the green pond at its foot. You don’t get that in California. That is Bengal, and that is [here Renoir used the one word that in his vocabulary meant wholehearted approval] fantastic.’

Among other things which Renoir thought fantastic and hoped to use in his film were a temple on the bank of the Hooghly (‘so humble … maybe one man built it, and maybe the same man worships in it’); a boat – any boat – on the river (‘ageless, like an Egyptian bas-relief’); a woman drawing water from a well; saris hanging from the verandahs of Bowbazar residences; the music of an anonymous flautist in Waterloo Street; the patterns of cow dung on the wall of a village hut …

Cinema being first and foremost a pictorial medium, and the integrity of atmosphere being the first essential of a good film, the problem which faced Renoir and which his painter’s eye was able to solve with comparative ease was that of selecting the visual elements which would be pictorially effective, and at the same time truly evocative of the spirit of Bengal. And because the narrative technique of cinema admits of dawdling, these elements had to be the quintessential ones so that the director could make his points and create his atmosphere with a minimum of film footage.

Search for style

In searching for locations, therefore, Renoir was also searching for a style. But being an alien and a European, there is a limit to which he could probe into the complexity that is India. The most he could do was to concentrate on the external aspect and leave the rest to his own French sensibility.

In cinema, as in any other art, the truly indigenous style can be evolved only by a director working in his own country, in the full awareness of his past heritage and present environment.

In the days of the silent cinema, the film-makers of the world formed one large family. Using the technique of mime, which is a more or less universally understood language, they turned the cinema into a truly international medium. With the coming of sound, mime gave way to the spoken word and a new technique of realistic acting was evolved to suit the requirements of the medium. Not that stylization had to go. As Chaplin has demonstrated in Monsieur Verdoux, an Englishman can make a film about a Frenchman in an American studio, and yet invest it with a basic universal appeal. But the main contribution of sound was an enormous advance towards realism, and a consequent enrichment of the medium as an expression of the ethos of a particular country.

For is there a truer reflection of a nation’s inner life than the American cinema? The average American film is a slick, shallow, diverting and completely inconsequential thing. Its rhythm is that of jazz, its tempo that of the automobile and the rollercoaster, and its streaks of nostalgia and sentimentality have their ancestry in the Blues and ‘Way down upon the Swanee river’. Yet it must be reckoned with, as jazz is real and the machine is real. And because cinema has the unique property of absorbing and alchemizing the influence of inferior arts, some American films are good, and some more than good. The reason why some notable European directors have failed in Hollywood is their inability to effect a synthesis between jazz and their native European idioms. Those who have retained the integrity of their style have done better. We may mention the films of Ernst Lubitsch and Fritz Lang, and one of the very best, Renoir’s The Southerner, which is American in content but completely French in feeling.

French films

The French cinema itself is perhaps the richest in its absorption of all that is best in French culture – in its painting and poetry, its music and literature.

One of the main reasons for this is the prevalence of avant-garde experiments in which, apart from professional film-makers, writers like André Malraux, Jacques Prévert and Jean Anouilh, painters like Fernand Léger and Man Ray, musicians like Arthur Honegger and Darius Milhaud participated. The spirit of experiment persists even in the commercial cinema, so that Jean Cocteau takes an innocuous and touching fairy tale, embellishes it with Dadaist touches and makes of it a commercial and artistic success.

In Monsieur Vincent, one of the great films of our time, there is a scene which shows Vincent spending a night in a French slum in the ramshackle garret of a young man afflicted with a wasting disease. As Vincent lies in the darkness and deathly quiet of the room, snatches of neighbourhood sounds begin to seep in through the skylight – the drone of a hurdy-gurdy, the monotonous rat-tat of a handloom. The sick man begins to make wry consumptive comments which identify and illuminate each individual sound, while all the time the camera holds on the shadowy form of Vincent’s head, only a gleam in his left eye showing that he is awake and alive to his surroundings. This one scene, lasting barely a minute and a half, reveals the poetry and subtlety, the humour and humanity of the best French cinema.

Possessing neither the subtlety and emotional candour of the French, nor the bravado of the American, the British cinema had to go through a particularly ignominious period until the war, and the consequent expansion of the documentary gave the needed impetus. Since then we have had films like Brief Encounter, The Way Ahead and This Happy Breed which have caught the national character admirably. But the fondness for half-shades and other genteel qualities we recognize as British is not exactly conducive to good cinema. Hence the frequent falling on fantasy (Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger), on Shakespeare (Laurence Olivier), on Dickens (David Lean). At present the future well-being of the British cinema lies in the hands of a handful of directors gifted enough to overcome the ethnological handicaps.

As an extreme form of indigenous style, one may mention the early films of the Ukrainian director Alexander Dovzhenko, which were largely incomprehensible – even to Russians outside their own province – not because of their language (they were silent) but because of the obscure allusions to local customs and legend. On the other hand, in the great formalist epics of Sergei Eisenstein there is a return to the broad and universal gestures of mime. Somewhere between the two extremes lies a film like The Childhood of Maxim Gorky, as poignantly evocative of the soul and soil of Russia as Fydor Dostoyevsky or Modest Moussorgsky.

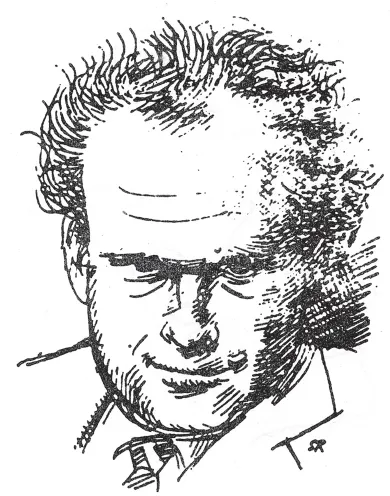

Sergei Eisenstein

(sketch by Satyajit Ray)

Indian effort

But what of our own Indian cinema? Where is our national style? Where is the inspiration to transform the material of our life to the material of cinema?

Apparently, even the external truth which Renoir was striving after has not bothered our film-makers. Of our film-producing provinces, Bombay has devised a perfect formula to entice and amuse the illiterate multitude that forms the bulk of our film audiences. Bengal has no such formula, nor the technical finesse which marks the products of Bombay. But Bengal has pretensions. And the average Bengali film is not a fumbling effort. It is something worse. It is a nameless concoction devised in the firm conviction that Great Art is being fashioned. In it the arts have not fused and given birth to a new art. Rather they have remained as incongruous and clashing elements, refusing to coalesce into the stuff that is cinema. And so painting finds its expression in backdrops, music in the spasmodic injection in ‘song numbers’, literature in the unending rhetoric of the idealist hero, theatre in the total artificiality of acting and décor. The few freakish exceptions do not make amends and do not matter.

The pity is that there are few countries more filled with opportunities for film-making. Evidently it is the imagination to exploit these opportunities that is lacking. But there is some cause for optimism. Except in some superficial technical aspects, our films have made no progress since the first silent picture was produced thirty-five years ago, which means that there is time to learn anew and begin from the beginning.

So let us start by looking for that clump of bananas, that boat in the river and that temple on the bank. The results may be, in the words of Renoir, fantastic.

![]()

2

NOTES ON FILMING BIBHUTI BHUSAN

WHAT INSPIRED YOU to make Pather Panchali?

Bibhuti Bhusan

This is a question I have often been asked. The simplest and truest answer would of course be that it is one of the most filmable of all Bengali novels. But this would not satisfy those who hold that the stuff of Bibhuti Bhusan Banerjee is not the stuff of cinema. They would admit, even acclaim, the greatness of the literary original, but would say at the same time that it is not natural film material.

Satyajit Ray directing Chunibala Devi, who played Indir Thakrun in Pather Panchali

This betrays an ignorance of things filmic. One can be entirely true to the spirit of Bibhuti Bhusan, retain a large measure of his other characteristics – lyricism and humanism combined with a casual narrative structure – and yet produce a legitimate work of cinema. Indeed, it is easier with Bibhuti Bhusan than with any other writer in Bengal. The true basis of the film style of Pather Panchali is not neorealist cinema or any other school of cinema or even any individual work of cinema, but the novel of Bibhuti Bhusan itself.

Many have taken exception to the omissions from the novel, but I can say with conviction that no extended work of fiction has ever been translated to the screen without considerable excision. It is not that no novel exists which can be filmed in its entirety. If mere recounting of incidents was involved, almost any novel could be translated. But it would be a translation faithful to the letter and not to the spirit. In order to achieve both, one needs span, space and breadth. In other words, footage.

It is a global convention that a film has to be kept within a certain length (usually the equivalent of a long short story) to qualify for commercial exploitation. As long as one accepts this convention and also expects filmed novels, one cannot be too demanding about strict adherence to the letter. Transformation, therefore, is inevitable.

Although the film of Pather Panchali left out much from the book, what remained so closely conformed to what people liked in the book that the omissions were largely forgiven.

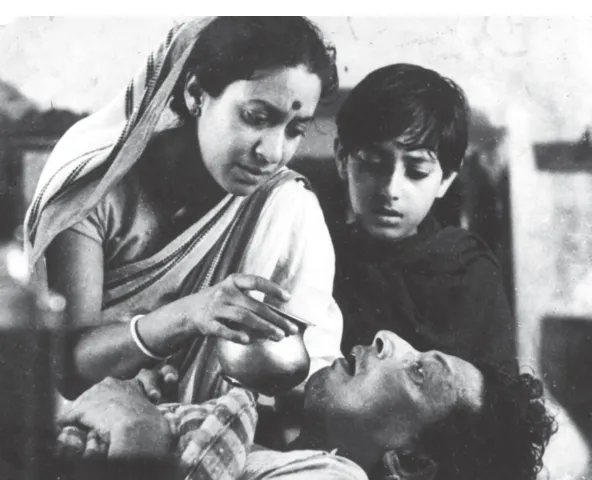

Death of Harihar (Kanu Banerjee) in Aparajito

The case of Aparajito is different. The book I consider to be a lesser work than Pather Panchali, although it is not by any means wholly lacking in the qualities that mark out Bibhuti Bhusan from other writers.

Why then did I choose to make a film of it? The reason is that there are two aspects of the book which fascinated me enormously.

One was the cinematic possibilities (by which I imply both visual and dramatic) of the contrast between the three main locales in the first half of the novel – Benares, a typical Bengali village, and the city of Calcutta.

The second aspect – and the more important one – was the relationship between the widowed mother and the adolescent son, intensely dramatized by a profound revelation of the author’s: Apu, upon learning of his mother’s death (says Bibhuti Bhusan), had a feeling – even if momentary – of a freedom from bondage. This would be a daring thing for anybody at any time to say, and it was the mainspring of the screenplay which, in its broad outlines, corresponds at least as closely to that particular portion of the original book as does Pather Panchali.

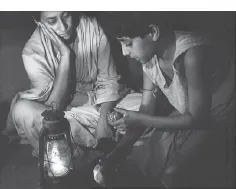

Mother and son in Aparajito

The Lila episode might have been worked into this scheme had it been feasible commercially to have made the film three quarters of an hour longer than the finished length of Aparajito.

A word to the critics who complained (although I myself chose to take it as a compliment) that my films often had the look of pictorial reportage: the pictorial and the docume...