eBook - ePub

Available until 27 Jan |Learn more

The Utopia of Film

Cinema and Its Futures in Godard, Kluge, and Tahimik

This book is available to read until 27th January, 2026

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 27 Jan |Learn more

About this book

The German filmmaker Alexander Kluge has long promoted cinema's relationship with the goals of human emancipation. Jean-Luc Godard and Filipino director Kidlat Tahimik also believe in cinema's ability to bring about what Theodor W. Adorno once called a "redeemed world." Situating the films of Godard, Tahimik, and Kluge within debates over social revolution, utopian ideals, and the unrealized potential of utopian thought and action, Christopher Pavsek showcases the strengths, weaknesses, and undeniable impact of their utopian visions on film's political evolution. He discusses Godard's Alphaville (1965) against Germany Year 90 Nine-Zero (1991) and JLG/JLG: Self-portrait in December (1994), and he conducts the first scholarly reading of Film Socialisme (2010). He considers Tahimik's virtually unknown masterpiece, I Am Furious Yellow (1981–1991), along with Perfumed Nightmare (1977) and Turumba (1983); and he constructs a dialogue between Kluge's Brutality in Stone (1961) and Yesterday Girl (1965) and his later The Assault of the Present on the Rest of Time (1985) and Fruits of Trust (2009).

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Utopia of Film by Christopher Pavsek in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Film & Video1

What Has Come to Pass for Cinema

FROM EARLY TO LATE GODARD

Utopia and Its Passing

It might be useful to consider Godard’s career as if it followed a somewhat disordered, almost reversed chronology than the transition from modernism to postmodernism. By this view, Godard’s early films would be the properly postmodernist work, indulging in pure pastiche, working almost exclusively with surface play, chance, the fragmented and decentered subject, as well as reveling in the dedifferentiation of the categories of mass culture and high art. The euphoric celebrations of westerns and films noir in his articles for Cahiers du cinéma would fit nicely with such a characterization, and the later remakes of his early work (the Hollywood version of Breathless [Jim McBride, 1983] with Richard Gere) as well as the focus of his contemporary postmodern followers on the films of the early sixties (Quentin Tarantino’s obsession with the early Godard, most notably emblematized in the naming of his production company after Band of Outsiders [Bande à part, 1964]) would seemingly offer support for this periodization as well. Paradoxically, then, Godard’s early period would usher in a political moment, an impulse thought to have been vacated in the postmodern. This moment of modernist engagement would be followed by his experiments with video and television, a medium chronologically much newer than cinema that would lead him into the past. For oddly enough, video would spawn the rebirth of cinema for Godard, to which he would return in 1980, when he began to produce properly high modernist works. The films of the last two decades have much of the feel of “autonomous” works of art produced by a great master in his retreat, cut off from the world; his home in Rolle, Switzerland, has become his Pfeiffering, the rural, isolated abode of Adrian Leverkühn in Thomas Mann’s Doktor Faustus. So it is that Godard finds himself, late in his career and by his account near the end of his own life as well as that of cinema itself, projected back into an earlier epoch producing art in a medium which, as Godard himself has said, was hitherto unable to assume its status as art.1

Appropriately, then, Godard has found his way to something that one may emphatically call “cinema” at a time when it has become a commonplace to speak of its death, a topic about which Godard has spoken and filmed as much as anyone.2 Conventionally, this has been seen as a nostalgic or sentimental streak in Godard. Commentators regularly write of the elegiac or pessimistic tone of his late works, from Passion (1982)3 to Histoire(s) du cinéma (1998) and the more recent work, In Praise of Love (Éloge de l’amour, 2001). Godard himself readily admits to such lamentations, but in an interview precisely at the beginning of this late period (1983) he has supplemented this view with a more optimistic one, even if he does continue to believe in cinema’s passing: “It is true that for the cinema I have a sentiment of dusk, but isn’t that the time when the most beautiful walks are taken? In the evening, when the night falls and there is the hope for tomorrow? Lovers rarely ever walk about hand in hand at seven o’clock in the morning… for me, dusk is a notion of hope rather than of despair.”4 A hope always attends this gathering of the “shades of night,” to paraphrase a favorite passage in Hegel that appears in Germany Year 90 Nine Zero (Allemagne année 90 neuf zéro, 1991); this moment of an end, of a coming to pass of not only cinematic history but virtually all history, for Godard is not solely tragic, is not merely an experience or moment of irretrievable loss, but is shot through with a utopian energy, a sense of openness and possibility from which something good can emerge. These two moments, of passing and utopia, do not exist in a neutral relation to one another, but instead are inextricably, dialectically, intertwined. So it is that a profound sense of utopia imbues even the most pessimistic seeming of Godard’s films, including the three which I will focus on here, JLG/JLG: Self-portrait in December (JLG/JLG—autoportrait de décembre, 1994) and Germany Year 90 Nine Zero, both films that are most definitely about the passing of many things, and Film Socialisme (2010), which is about their possible resurrection.

The Possibility of Love and Death

These films address Godard’s own passing, about which he is relatively sanguine as well. In JLG/JLG, whose very title already registers an end, images of an open notebook are intercut into a sequence of Godard playing tennis with a young woman. On one page is written: “The past is never dead.” On the next appears: “It hasn’t even passed yet.” Then comes an image of Godard playing tennis again, dressed in his familiar hat (all that is missing is his cigar), vainly flailing at a passing shot. He remarks to his playing partner or the camera, it is not clear which: “I am as happy to be passed as not to be passed.” This is the remark, perhaps, of a mediocre tennis player (by his own admission) but also of one who has lived a life fully. In the same 1983 interview just mentioned, Godard continues:

There is something, however, that I am beginning to find very beautiful in the cinema, something very human which gives me the desire to continue working in it until I die, and that is precisely that I say to myself that the cinema and myself may die at the same time… and when I say “cinema” I mean cinema as it was invented. In other words, cinema, which deals in human gestures and actions… in their reproduction, can probably only last, such as it was invented, for the duration of a human life. Something between 80 and 120 years.

This means that it is true that the cinema is a passing thing, something ephemeral, something that goes by.…

So now I accept that cinema is ephemeral. It is true that at times I felt differently, that I lamented the future, that I said “What will become of us?” or “How terrible,” but now I see that I have lived this period of cinema very fully.”5

This possibility of passing is precisely the generative moment; mortality is the horizon of life by which it is defined. Indeed, the generative moment of such caesurae is underscored in JLG/JLG by the sheer beauty of the images of winter, the images of December, dispersed throughout the film—a snow-covered lane with trees, the Alps hovering over the shores of Lake Geneva, even a dreary wet day, when all the snow has melted—which then give way almost unnoticed to lush images of early spring (figs. 1.1 and 1.2). It is as if through these landscapes Godard wishes to foreground this intertwining of ephemerality and beauty. And it is here that we come to the heart of a dialectic that underlies all of Godard’s work, one of death and resurrection, in which death is the precondition for the life that precedes it as well as the resurrection to come.

This resurrection is not, however, to eternal life. If in JLG/JLG a pessimistic or negative moment arises, it is not in the mournful reflections on Godard’s childhood or the recollection of the virtually instinctive knowledge he had as a boy that something was not right with the world, a knowledge that seems to have tainted the more joyful days he spent roaming his family’s various estates around Lake Geneva. Nor is it to be found in the sadness that accompanies the recognition of Godard’s own imminent mortality. Instead it arises as a consequence of the conflicted act of throwing one’s self into the world, of entering language or the symbolic order, of publicly being in the world at all. This potentially utopian act of subjective self-constitution is beset with enormous risks and the two moments cannot be separated, as another passage from the film reveals. Again, images of notebooks appear with Godard’s handwriting: “The temptation to exist.” “I am a legend.” A montage of shots of Lake Geneva follows, with waves breaking on the shores, the Alps and towns in the distant background. By the fading light of a match Godard writes an illegible text, and then his voice-over reads:

FIGURES 1.1–1.2 JLG/JLG: Self-portrait in December (Jean-Luc Godard, 1994). Still capture from DVD.

When we express ourselves we say more than we want to. We think we express the individual but we speak the universal. “I am cold.” It is I who say I am cold, but it is not I who am heard. I disappear between these two moments of speech. All that remains of me is that man who is cold, and this man belongs to everyone.

As the last two sentences are heard, again the notebook appears: “I am legend.” “The eternal house.” The thought image that emerges from this montage is laced with a figure of utopia that is a constant throughout the entirety of Godard’s career. Similar passages on language which bear within them a sense of a post-individual inter- or trans-subjectivity appear as early as Two or Three Things I Know About Her (Deux ou trois choses que je sais d’elle, 1967). But more than this, the very fact that the quote is unattributed (a hallmark of Godard’s later work), while perhaps considered a plagiaristic borrowing by critics concerned with outmoded notions of individual authorship and creativity, marks an uncanny way in which Godard himself, or his work, embodies a form of decentered, yet collective, subjectivity. In a telling remark during an interview in 1996, Godard cannot recall if the final words of JLG/JLG were his own or a quote: “I think it’s a quote, but now to me quotes and myself are almost the same. I don’t know who they are from; sometimes I’m using it without knowing.”6 Far from being a vanity of his, as if he presumed to be of a quality of mind capable of the thought of a Heidegger, a Sartre, or a Hegel, this remark instead points to the objective preconditions for Godard’s own expression: his passage into language, the house in which he lives, is predicated on the passage into language of those before (and beside and after) him. Subsequently this expression of a self through citation passes into an emptying of the self, a dispersal into citability in which all belong to him and he belongs to everyone.

This image of subjective passing relieves the film itself, the work of art, of the burden of bearing authorial intention. It is here that we can locate a significant thrust of the late Godard’s (cultural) politics. Again, in an interview, Godard has made comments of relevance to this context:

I believe in man as long as he creates things. Men have to be respected because they create things, whether it’s an ashtray, a zapper, a car, a film or a painting. From this standpoint I am not at all a humanist. François [Truffaut] spoke of “auteur politics.” Today, all that is left is the term “auteur,” but what was interesting was the term “politics.” Auteurs aren’t important. Today, we supposedly respect man so much that we no longer respect the work…. I believe in the works, in art, in nature, and I believe that a work of art has an independent purpose that man is there to foster and to participate in.”7

When Godard speaks of the “work” or “works” here, one should understand these terms to refer to both the productive process in which an artist (or any person) engages during the creative act, as well as the object produced. The work of art is, as process and object, to use language more Adorno’s but wholly appropriate here, evidence of the manner in which subjectivity is and becomes objective, in which a subjective intention or impulse, predicated on a preexistent objectivity, alienates itself (willingly) into a work that will take on an autonomous life of its own, one in which the auteur is little more than a vanishing mediator. (To this theme of objectified subjectivity I will return shortly.) In this way one could say that Godard is a committed materialist, one perhaps more consistent and consequent than the one of the Maoist period.

But I have asserted that this utopian moment of subjective passing bears a certain risk, a potentially negative or mournful moment that it must always confront. Where is that mournful image to be found in JLG/JLG?8

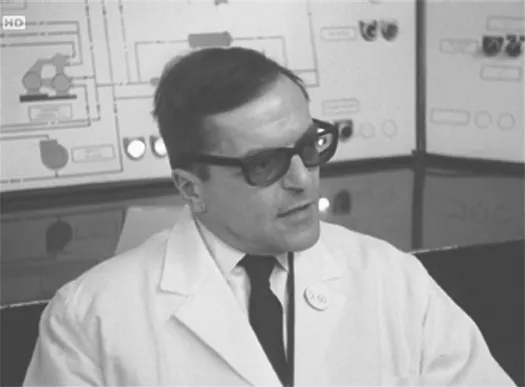

The image in Godard is never singular; it is always at least double. To the viewer familiar with Godard’s work, the notion of the “legend” in JLG/JLG immediately calls to mind the great confrontation between Lemmy Caution, hero of Alphaville (Alphaville, une étrange aventure de Lemmy Caution, 1965), and Professor von Braun, creator of Alpha 60, the monstrous computer that (who?) regulates that tenebrous city of a reason so total and utterly reduced to mere calculation that it has turned over into unreason (fig. 1.3):

VON BRAUN: Look at yourself. Men of your kind will soon no longer exist. You’ll become something worse than death; you’ll become a legend, Mr. Lemmy Caution.

LEMMY: Yes, I’m afraid of death, but for a humble secret agent, death is a fact of life, like whiskey, and I’ve been drinking it all my life.

Lemmy’s rather clever reply, his full embrace of the inevitability of death as a “fact of life,” is perfectly consistent with the dialectic of life and death. But his answer sidesteps the true issue von Braun presents to him: the real threat is not death but the status of being a legend, the resurrection to immortality. The legend is the downside of the objectification of the subject in the work, of daring to lead a public life; it is a form in which all particularity and historical specificity is lost. It is the image of the abstract universal, a far cry from the universality of which Godard speaks in JLG/JLG.

At the end of JLG/JLG, Godard (perhaps in vain) issues a corrective to this status, a plea for a modest reception of his objectified self as the work of “a man, nothing but a man, no better than any other, but no other better than he.”9 But this is simultaneously a plea for the works as well, for to respect the work is to respect the man. While in language or art the individual (or collective) producer “disappears” and becomes universal, belongs to “all,” the danger exists that he will become legend, reified into the great auteur, a fate with inevitable consequences for the works themselves. Each of Godard’s films is implicitly (in JLG/JLG it is explicit) an attempt to shatter this status as legend, to “carelessly,” as he notes in JLG/JLG, and repeatedly (even against his will)10 attempt to thwart the expanding present of the status of legend, to in a sense make a plea for the author’s and his work’s own mortality.

FIGURE 1.3 Alphaville (Jean-Luc Godard, 1965). Still capture from DVD.

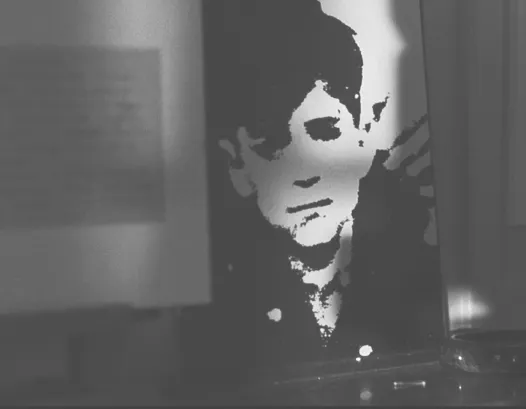

In the confrontation with his status as legend staged in JLG/JLG, Godard adopts the familiar standpoint of the artist producing a self-portrait. As Gavin Smith points out, the presence of the artist is felt in the shadow of the camera and the cameraman that falls over an image of a photograph of Godard as a child in JLG/JLG (fig. 1.4). Godard’s characterization of this gesture is very apt: “Just for once, I thought of the audience—a small one, so that it understands that it’s ‘me and me.’ [It’s like with] painters’ self-portraits, painting themselves holding the palette and paintbrush.”11 Whereas this position might be seen as an attempt to secure a stable image of the artist for posterity, Godard’s effort here is more open-ended, as indicated by the turning of empty pages of the very notebook where “I am legend” is written, empty pages that “seem like another image of the future, of history still to be written” as Gavin Smith has gracefully noted.12

FIGURE 1.4 JLG/JLG: Self-portrait in December (Jean-Luc Godard, 1994). Still capture from DVD.

Instead, Godard is creating and adopting a position of distance from this master signifier (himself as “legend”) that calls its very stabilit...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Series Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: The Idea of Cinema

- 1. What Has Come to Pass for Cinema: From Early to Late Godard

- 2. Kidlat Tahimik’s “Third World Projector”

- 3. The Actuality of Cinema: Alexander Kluge

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index