![]()

PART I

The Accusation

MARCH 18, 1982

When I was twelve years old I took acting lessons. I wanted to be an actress, preferably a child star, and when a tiny school of drama, dance, and voice with the impressive name of Theatre Arts Showcase opened in my neighborhood, I convinced my mother to pay a dollar weekly for a two-hour class session in acting. There were four other prepubescent girls, none of them as fiercely determined as I. Our teacher was a forty-year-old mustachioed man who wore a brown belted suit and worked full-time as a shoe salesman, but the Executive Director of the school, his wife, told me that he had once been in professional theater in Chicago. I was awed enough, mostly by her, the most exquisite, sophisticated blond creature I had ever seen in our dark lower-middle-class community. She was my first love.

Her husband must have been perplexed about what to do with five little girls, four of them envisioning themselves as the Lana Turner of the next decade. There were few scripts for four twelve-year-old Lana Turners and one twelve-year-old Sarah Bernhardt, but for our second session he brought us a fifteen-minute scene in which we could at least all participate, and he kept us working at that scene for the next seven or eight months, until, one by one, all the girls but me dropped out of the class. The scene was from Lillian Hellman’s The Children’s Hour. I played Mary Tilford, an adolescent bully. He told us nothing about the play, and I aspired to thoroughness in my acting, so I went to the neighborhood library where I found and read a copy of The Children’s Hour. I was mystified, despite my own powerful crush on the Executive Director. I understood from that first reading that Mary Tilford had fabricated a tale, claiming that her two women teachers, who operated a girls’ boarding school, were doing things they were not supposed to be doing, but I could not quite understand what those things were.

The play was in the adult section of the small library, and since I only had a juvenile’s card I could not check it out, so I returned to reread the play three or four times over the next months. Finally I understood that the two teachers were ruined because Mary Tilford had accused them to her grandmother of being “in love with each other,” and the grandmother had informed all the other parents, who promptly removed their children from the school. No one had ever told me before that the sort of thing I felt for the Executive Director could ruin someone. I was profoundly dismayed, and I continued to be dismayed (although my devotion to the Executive Director never wavered) for the next two years, until my mother and I moved to the other side of town, where I was too far away to continue my acting lessons.

Years later, as a sophomore at NYU, I happened on the play again when I was assigned to read Hellman’s The Little Foxes for a course in American drama. By this time I had had a couple of adventures, and I had taken on a certain patina of sophistication. There was little that would have dismayed me—or rather that I would have admitted dismayed me. But the play had now some sentimental value for me. I associated it with the days of my painful naïveté and my first love. And then I came to think of it as part of a precious cache of secret knowledge, along with books such as The Well of Loneliness and Regiment of Women and We Walk Alone. That the characters in these works invariably ended badly did not surprise me, nor did it disturb me as much as it should have. I was only gratified that there was some mention of the unmentionable in print. I brought them up in conversations very rarely and always carefully—only when I suspected that the other person had had experiences such as mine and I was seeking to open the subject with her. They were sort of coming-out tools.

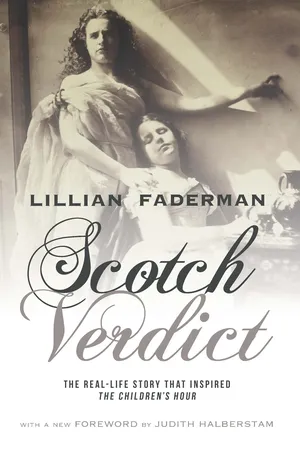

When I and my environment had changed so that I no longer had a need for such tools, I was furious with the authors for sending their female characters off to hell or suicide or insane asylums, and then I forgot them. I had not thought about The Children’s Hour in at least ten years, until I began research for a dissertation on the popular treatment of women under the law. I found several books by a popularizer of legal history, a Scottish law historian named William Roughead, and in one of them, Bad Companions, which had been published in 1930,1 discovered the source for The Children’s Hour.

I was intrigued by what Hellman had changed from Roughead’s thirty-page account. She set the incident in America, in her own day. It had actually taken place in Scotland, in the early nineteenth century. In her play Mary Tilford is an American girl, her grandmother’s favorite. In reality she was at least half Indian, the putative illegitimate child of a very young Scotsman who went to India and died there. The Scottish woman who accepted the title of her grandmother had many legitimate, purebred grandchildren, and she merely tolerated the girl; but she believed her tale because she could believe less that a young female under her charge could invent such a story. In Hellman’s play the two women sue the grandmother for libel, lose their suit—and one of them, with all the advantages of a Freudian knowledge of neurosis, admits she has long harbored repressed lesbian passions, and she shoots herself.

I was fascinated with the legal aspects of the case as Roughead presented it, but even more fascinated with the two women, Marianne Woods and Jane Pirie. In their fictional form I, as Mary Tilford, had once done them in, and later I had called on them as secret sisters. They had lived with me through my first love in childhood and through my cunning and fear in young adulthood. And now I discovered that they had once really existed. I knew that Roughead had based his accounts on trial records that were then extant. Since the case had been appealed to the House of Lords in London, I assumed all the transcripts were there. I wrote to the Secretary of the House of Lords Record Office, with whom I had had correspondence in looking for other trial records for my dissertation, and I received from him some incomplete pages of the appeal transcript. I was sure that many more pages of transcript must exist, and that they were probably housed somewhere in Scotland. I wanted to drop my dissertation and run to Scotland and find them, wherever they were moldering, probably in the law libraries of Edinburgh.

Instead, I finished my dissertation, which included a study of 156 other women as they were treated in popular accounts of the workings of the law. And I went on to one more project, which led to another, and then another. But although I have now forgotten most of the 156 cases I once studied, I remember Miss Woods and Miss Pirie. The Woods and Pirie case was one of a dozen I came across of women before the twentieth century who were accused in the courts of lesbianism, yet only theirs really touched me—partly because of my early associations with them, I suppose. But even more, I felt somehow that I knew them, and that I wanted to know them better. They were teachers, as I am; they had been well trained in constraint and propriety, as I was; and yet Jane Pirie, despite her training and surface calm, was fierce and given to outbursts of violent passion, just as I am. I wanted to know whether they were really guilty of what they had been accused, what words were used to make such accusations in their day, how they defended themselves, how their judges responded, what happened to women like them after such an experience in the early nineteenth century, what might have happened to me had I, with my temperament, lived then instead of now.

I knew that whether or not men truly believed it, whether or not their personal experiences bore it out, the spoken consensus about the good middle-class woman of the late eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries in Britain was that she was passionless: both her instincts and her socialization kept her chaste until marriage, and once married she became a sexual being only to do her duty to her husband and to help repopulate Britain. If it was agreed that women had no sexual drive in relation to men, then surely it was inconceivable that they might feel sexual passion for each other.

But I wanted to know what a woman’s life would be if she did feel sexual passion for another woman. Or if someone, perhaps someone raised on a different social level or in a different culture, where women were thought of as sexual creatures, less madonna and more whore—if that person said she did. What if a girl raised in India, or among the lower orders, raised where flesh was barer, where women were segregated from men and yet exposed always to chatter about sex, or where the delicacies and stringencies of middle- and upper-class Anglo-Christianity had no hold—what if such a girl (for a lark, for revenge, or in truth, like the boy in “The Emperor’s New Clothes”) said that she saw two respectable women copulating together?

What if in 1810 in Scotland she said that in the middle of the night, night after night, in the dormitory where she slept, she had seen two school mistresses, Christian women, in bed together, not only kissing and caressing, but going through motions that resembled sexual intercourse? Whether she told the truth or she lied, who would believe her? And if she was believed, what would happen to the school mistresses?

The research I did for my dissertation gave me only cursory answers. And then I forgot about my questions for years. But tonight, for some reason—perhaps because I am between projects now, and while my body luxuriates in leisure my mind abhors it—I thought of the Scottish school mistresses and I told Ollie about them. Talking to her, I suddenly wanted very much to find out what really happened to them. I decided to go to Edinburgh this summer.

Ollie said she would like to come with me. She needs to revise her manuscript, which she has just completed in first draft, but she thinks she would be able to work in Scotland just as well as in New York.

JUNE 7, 1982

Coming from the airport last Wednesday afternoon, our taxi sped through some residential streets not far from the university. I caught a brief glimpse of a group of about ten school girls, all dressed in green monogrammed blazers, gray skirts, and green knee-high socks. I craned to see them as we passed, wanting images I could hold in my mind for the faces of Miss Munro and Miss Stirling and all the others. The taxi moved too quickly and I could not make them out individually. I was left only with the impression of round pink cheeks and smooth brown hair. Most of them were probably ten or twelve, much younger than the important girls in my drama, but about the age of Miss Hunter and the younger Miss Dunbar. Not an Indian girl among them, but I have no trouble seeing her. Her skin is quite brown. I thought at first that she might have British features superimposed on that dark skin, but I don’t picture her that way now. She is very much Indian, of the large type rather than the delicate, with heavy eyelids.

I have spent all week, since Ollie and I arrived here, peering at faces. I think if I can fix pictures of all these people in my imagination I will write about them more clearly. Fashion changes, and customs change—but faces and characters must repeat themselves through the generations. I believe I have found the modern counterparts of most of the principals in the case.

For Charlotte Whiffin, the maidservant, my image is a girl I saw Friday night in a working-class disco that we happened into after an early dinner. The place was almost empty. She was on the floor, gracelessly dancing at a distance from her partner, barely lifting her feet or moving her body. They both, but she especially, looked bored—worse than bored, lifeless, without passion or hope. She is stocky, white-skinned, pimply. Several times while she danced she nervously tucked her white blouse into her blue skirt with her thumbs. I imagine her life to be almost unalloyed drudgery. She is probably a waitress. Nothing can transform her from the drudge she has become since she left childhood, not even “going out for a good time.” I think she gossips viciously, losing herself in the meanest smears, which perhaps alone have the power to give her a jolt of life. What else could claim her interest?

I found two Marianne Woodses. The first was a young Marianne, about nineteen. I saw her on a bus that Ollie and I took to the National Library the day after we arrived here. She was very erect and stately for so young a girl, lovely and cold. She sat entirely still, aloof, removed. Noli me tangere. Who would dare to touch her? At her stop she glided off the bus. She was perfect in a manner that makes me unreasonably irritated.

The second Marianne Woods I found on Sunday. I wanted to go to St. Giles’s because it had been the largest Presbyterian church in Edinburgh even when Jane Pirie was alive, and I think she must have come there often, at least during her childhood since it is near Lady Stairs Close, where she had lived. The associate preacher is a woman. I almost didn’t notice her until Ollie said, “There is your Marianne Woods.” She was right. There was Marianne Woods at about thirty-five, still erect and lovely despite a pockmarked face that relieves her from perfection. And she had been made more human by sorrow and the years. She read the closing prayer in a voice that was self-assured and intelligent. I suppose many of her parishioners are in love with her. You would still not dare to touch her, but you might hope that from her stately position she would deign to touch you.

I could find Jane Pirie nowhere, although I searched for her harder than for any of the others. Finally, this morning, I realized that whenever I looked for her, I myself appeared in my mind’s eye: not my face but—what shall I call it?—my soul, my temperament, whatever I am inside.

Ollie has a cold. I feared that would happen to one of us, since it was 96 degrees Fahrenheit when we left New York and 41 when we got off the plane in Edinburgh. Where does one find chicken soup in Scotland?

JUNE 10, 1982

I actually had my hands on the complete, original trial transcripts today in the Signet Library. When the librarian first brought them out to me, I felt so awed that I was almost afraid to touch them. She must have thought I believed I was looking at the Magna Charta. Finally I went through the whole lot, very gingerly, to see what was there. There are over eight hundred pages. I intend to read through all the transcripts first to get a clearer picture of Jane Pirie and Marianne Woods and the others. Then I will go back and examine the trial itself.

Thus far I have been able to find little about the mistresses’ backgrounds. Both had been governesses before they opened the girls’ boarding school. How else might they have supported themselves in that day?

If her father’s fortunes remained stable a girl of the middle class in early-nineteenth-century Britain could expect to drift into young ladyhood in the same idleness she had known from childhood, awaiting the suitor who would remove her from her patriarchal home into his. If her father’s fortunes became uncertain, however, or if his hold on middle-class status was never more than precarious, a young lady who was still unclaimed at the age of seventeen or eighteen might have felt obliged to seek employment. But there were few kinds of jobs open to her.

In previous centuries there had been a number of trades that were considered appropriate for females of her class, but gradually those trades were taken over by men and they were now thought neither appropriate for her nor attainable. The universities were closed to her so she could not hope to train for a profession. And most professions were anyway closed to her. If she had some literary talent she might join the ranks of the popular lady novelists who were just beginning to emerge at this time. If not, her choices were few: she could be a paid companion to a wealthy woman or a teacher of some sort—giving private lessons, teaching in a school, or living with a family as a governess.

Governesses had been fixtures in upper-class households since Tudor days, but in the late eighteenth century, with a rising middle class that had pretensions to refinement, the number of governess positions grew, so that a genteel young lady who had to support herself would have had little trouble finding employment—if not in an upper-class household, then in a home not too socially disparate from the one in which she had grown up.

Such a young lady would probably have learned the rudiments of culture in her own home. Perhaps she too had had a governess who taught her reading, writing, some history and geography, some mathematics, along with sewing and embroidering. Or perhaps her mother had taught her these subjects. She may have been sent to a gentleman once a week to learn French and to a lady to learn music. Or possibly she had been at a boarding school, which was becoming a popular option for the education of middle-class girls by the end of the eighteenth century. Wherever she had got her education, it was rarely thorough, but it was considered sufficient to allow her to teach other young ladies.

However, while she might have found a governess’ position without much difficulty, the literature of the period suggests that it was not very likely she would have been happy in her role. Mary Wollstonecraft complained at the end of the eighteenth century that a governess’ chances of meeting with a reasonable employer were not better than one in ten, that having hired a governess the lady of the house would “continually find fault to prove she is not ignorant, and be displeased if her daughters do...