![]()

PART ONE

THE VANISHING CURES

![]()

1

THE DRUG DISCOVERY CRISIS

One recent morning I received an e-mail message with the subject line “Sad News.” As I clicked on the message title and the full message popped up, I expected to hear of the passing of a distant colleague, someone whose retirement party I might have attended long ago as a graduate student, or a senior emeritus faculty member I might have met when I was in college. Instead, I was shocked to learn that my friend Darin had died of cancer at age 36.

I soon learned that Darin had been diagnosed with liver cancer some months before. He had undergone chemotherapy, without success. He had a transplant operation and had been recuperating at home, feeling somewhat better. Ultimately, the transplant didn’t take, and he began to get spiking fevers and became extremely ill. A month earlier he had gone into a hospice, and he then passed away one quiet Thursday, the day I received the e-mail message.

When we were 18, Darin and I spent a year traveling around Israel together on an organized program; we used to debate such minutiae as the proper number of times to reuse a razor blade. I hadn’t spoken to him in years, but the news of his sudden death hit me unexpectedly hard.

Darin was exuberant and friendly, with a touch of a caustic wit. He invariably left me smiling to myself after a round of informal debate. Prior to his diagnosis Darin had been just reaching his stride, personally and professionally. As someone who has done research into the biology of cancer, I could imagine the lethal progression of his disease and the fear and anger he must have felt as the available treatments failed him. His life was ultimately left unfinished because of a small number of aberrant cells in his liver and a lack of effective drugs. With these somber thoughts, I groped for the meaning of Darin’s untimely passing.

Darin’s tragically short life is not unique. My cousin Daniel was 35 when he was dining downtown in New York City on a summer evening with his girlfriend; he suddenly collapsed from a seizure. He was rushed to the hospital, where he learned he had an extremely aggressive form of brain cancer. He succumbed within a year, causing a painful void in the lives of his friends and family.

Cancer is only one of many diseases that can appear unexpectedly. Lou Gehrig, the tenacious baseball player, was diagnosed at age 36 with a deadly form of nerve degeneration that would paralyze him and then claim his life. Woody Guthrie, the singer of mesmerizing folk ballads, succumbed to Huntington’s disease, which causes constant, involuntary dance-like movements and is ultimately fatal. Ronald Reagan, a former U.S. president, developed Alzheimer’s disease, leading to the erasure of his life’s memories.

THE SHRINKING NUMBER OF NEW MEDICINES

Vast hordes of researchers are working to find cures for nearly every disease known to medicine. With these keen intellects working diligently, competing fiercely to solve these mysteries, you would expect that no stone has gone unturned, and no avenue unexplored. Yet we have not found cures for most types of cancer. Other diseases, including Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s, Lou Gehrig’s, and Parkinson’s, remain depressingly void of curative therapies. Why?

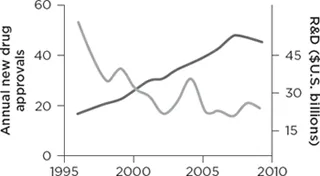

The United States and the rest of the world are facing a drug discovery crisis, a fact that has been evident to researchers for the last decade. The number of new drug approvals each year has declined more than 50% over this time, despite a massive increase in the amount of research funding devoted to drug discovery research. The cost and time needed for making each new drug is increasing dramatically, costing in excess of a billion dollars and taking more than a decade of late-stage research. Most importantly, researchers are finding fewer new drugs (see Figure 1.1).

Annual new drug approvals

Figure 1.1 The shrinking number of new medicines. Shown are the number of new drugs approved (defined as new chemical entities, NCEs) by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (gray line) and the amount of research and development funding by the U.S. pharmaceutical industry each year from 1996 to 2009 (black line). Despite a significant increase in research funding, the number of new drugs has plummeted, indicating a fundamental barrier exists to creating new medicines. Data sources: Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, Pharmaceutical Industry Profile 2010 (Washington, DC: PhRMA, March 2010), 26; Hughes, B., 2009 FDA drug approvals. Nat Rev Drug Discov 9, 90 (2010).

Despite the common perception of a boundless frontier, medical progress, measured in the form of new drug approvals, is in fact slowing.1 The pharmaceutical industry is in disarray, suffering from meager drug pipelines and laying off many employees. If the trend continues, patients face a bleak future in which dwindling progress will be seen against disease. We may have to adjust our expectations to that of a future in which many people inevitably succumb to tragic and painful diseases at all ages, with no substantial progress being made in creating new medicines.

This problem can be traced, at least in part, to an insurmountable obstacle that has stymied those who search for new medicines—the challenge of the undruggable proteins. These are the proteins that cannot be affected by drugs; these proteins, it is argued, lie beyond the reach of human ingenuity. These proteins are the ones that no drug has ever tamed.

WHAT IS A DRUG?

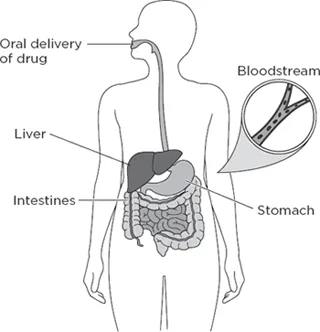

To understand the nature of these undruggable proteins and how they might ultimately be used to make medicines, it is crucial to understand what drugs are and how they function. When you swallow a pill, the drug inside that pill gets absorbed into your bloodstream, where it is distributed to the tissues in your body (see Figure 1.2). Many times, the drug is able to slip inside cells that make up these tissues and spread throughout the interior of cells, much like when you add a drop of ink into a cup of water.

The interior of a cell is made up of thousands of different proteins, which carry out most of the work of the cell. Proteins perform specific functions, like producing energy for the cell or enabling the cell to divide into two new cells. Such cellular processes require the coordinated activities of many different proteins. In terms of physical shape these proteins look like beautifully molded pieces of clay, each uniquely sculpted to suit its function. Some are long and thin, others are short and squat. Some have large holes in their middle, resembling a doughnut. Moreover, the surfaces of some proteins are smooth and featureless, while others are craggy and filled with crevices. In biology structure implies function, and this is true of proteins. Each protein has a shape that allows it to carry out its unique function within the cell.

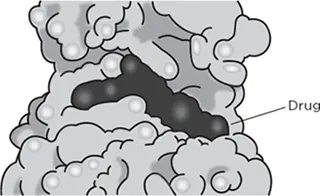

Drugs act by changing the function of a protein. To interfere with the function of a protein, a drug has to attach itself to a protein, fitting snugly into a crevice on the surface (see Figure 1.3).2

Figure 1.2 How a drug is distributed through an organism. When a drug is taken by mouth, it enters the gastrointestinal tract (including the stomach), is absorbed through the intestines, and enters the bloodstream. From there it is distributed to the different tissues and organs of the body in a way that depends on the specific molecular structure of the drug. In addition, as the blood passes through the liver, the drug gets chemically modified in a process called metabolism, which usually results in the drug being excreted through the kidneys into urine.

How does a drug stick to a protein and alter its function? Protein molecules are large, whereas drugs are much smaller than proteins. If a protein were the head of a life-size statue, a drug would be like an earplug sitting in the ear canal of the statue. Because of this difference in size, researchers call these drugs “small molecules”—they are small compared with proteins. Therefore, discovering a drug requires finding a small molecule that can stick to a specific protein and change its function. Such a protein is said to be the target of the drug.

Drugs stick to proteins when they have complementary shapes and properties. Think of putting a key in a lock or a square peg in a square hole. The shape of a drug must match the shape of a small indentation, or pocket, on the surface of a protein in order for the drug to stick tightly to the protein. This tight-fitting interaction between a drug and a protein is called binding. Yet shape matching is not enough for binding. The drug must also have the right amount of hydrophobicity (hai-droh-foh-BISS-ih-tee), or greasiness, in the right places. The drug must also have electrical charge and hydrogen bonds, or stickiness, in just the right positions. Moreover, a drug may cause the shape of a protein to change upon binding, like pushing a spoon into a soft clay sculpture. There are other, more complicated aspects of drug binding. For now, suffice it to say that it is generally difficult to find drugs that will bind tightly to a specific protein.

Imatinib bound to BCR-ABL

Figure 1.3 Example of a drug binding to a protein. The drug imatinib (black) is shown interacting with the BCR-ABL oncoprotein. The BCR-ABL protein is shown in gray in a space-filling model.

THE UNDRUGGABLE PROTEINS

Here is the surprising fact: All of the 20,000 or so drug products that ever have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration interact with just 2% of the proteins found in human cells.3 This means that the vast majority of proteins in our cells—many of which, in theory, can modulate disease processes—have never been targeted before with a drug.

Two responses to this news are possible. On one hand, you might be elated to discover that there is a huge reservoir of proteins that hasn’t been mined for new drugs and therefore be optimistic about the future of drug discovery and medicine. On the other hand, you might be pessimistic because you suspect that after decades of struggle, we have not found drugs that are able to bind to these proteins. In other words, perhaps the 2% of proteins that have been targeted with drugs are the only ones capable of being targeted.

What do the data tell us? Unfortunately, there is a fair amount of evidence suggesting that most proteins do not readily interact with drugs and that the more pessimistic scenario might be the correct one. For example, in a recent study at the pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline, researchers tested up to 530,000 different small molecules against 67 typical proteins in a series of screens. A screen is a large-scale experiment that involves testing many different small molecules—in this case, 530,000 small molecules were tested one by one to see if any of them can stick to any of these proteins.4

None of these 67 screens of 530,000 compounds resulted in a small molecule drug that could be developed for use in patients. Many such experiences have led some researchers to the conclusion that most proteins are undruggable—they are simply not capable of binding in a selective way to small molecules of the type that can become drugs.

Perhaps the molecules that were tested in these screens simply weren’t the right ones for the job. After all, even several hundred thousand molecules is an infinitesimal fraction of the number of possible small molecules that could be made in theory. This number of possible small molecules has been estimated to be on the order of 1060; that is “1” followed by 60 zeros. Thus, even testing a million compounds is not that many in terms of sampling a significant fraction of all possible small molecules. To get a sense of how big the number 1060 is, if all the possible drug molecules filled up the space of 10,000 different planets, then 1 million chemicals would be represented by just a single molecule on a single one of these planets. All of the remaining molecules on all of the planets would still remain to be tested.

Nonetheless, researchers are only human. If you have a negative experience at something, you are less likely to try it again. If you have 67 negative experiences at screening small molecules, you are going to try hard to make the 68th experience a positive one. Thus many researchers have become risk averse, mainly in regards to selecting proteins to design drugs against. They do not want to pick an undruggable protein to study and end up failing to find a small molecule inhibitor.

I know how powerful this aversive conditioning can be. When I was a graduate student, I devised a screen to search for small molecules that could block the action of a specific protein, called TGF-beta (for transforming growth factor beta), which is involved in the formation of certain tumors. I developed a rapid test that would allow me to run this screen efficiently.5 I then tested 16,000 synthetic small molecules and was deflated when I found none that were able to block the effects of TGF-beta on cells.

Not to be deterred, I decided to try testing some additional small molecules. This time, I tested different types of molecules—a set of 200 extracts obtained from marine sponges, provided to me by Phillip Crews. Phil and his colleagues travel the world to exotic locales, dive deep into the ocean to find unusual marine sponges, and then purify small molecules from these sponges using an extraction procedure.6 In this procedure the sponge is mixed with an organic solvent—similar to the one used in dry cleaning clothes—to separate small molecules within the sponge from other material.

Each of these extracts typically has several dozen different small molecules together in a mixture. I tested these 200 extracts, not expecting to find anything. After all, if I didn’t find any active molecules from among 16,000 synthetic chemicals, what was the chance I would find an active one in only 200 natural product extracts? I was surprised when one of these 200 extracts had a dramatic and striking ability to completely block the effects of TGF-beta in my test. I repeated this result several times to be sure. This is one of the first things researchers like to do when they get an exciting result—try to reproduce it a number of times to make sure it is real. Judah Folkman (who was both a surgeon and a basic scientist) once said that the difference between surgeons and basic scientists is that when someone can’t reproduce the results of a basic scientist, the scientist becomes alarmed. When someone can’t reproduce the results of a surgeon, the surgeon takes it as a compliment to their superior skill.

After confirming the result, I worked with Phil and his lab members to purify the single compound that was responsible for this striking activity. We went through several rounds of purification until we arrived at an active mixture of two or perhaps three chemicals, and we knew that one last experiment should separate them from each other. This was the pivotal moment, and I remember my anticipation. I was about to discover a powerful new natural product.

Despite my excitement, I carried out the last test carefully and methodically, wanting to be 100% sure of the result. The way I determined the effect of TGF-beta on these cells involved measuring the amount of cell proliferation occurring by placing a piece of film on a plastic dish containing the cells and then looking to see whether a dark spot appeared on the film. When I treated the cells with TGF-beta, the dark spot would disappear. The natural product I was chasing caused the dark spot to reappear, thus blocking the effects of TGF-beta on these cells.

After doing this last experiment, I went into the film development room and laid the film down onto the dish containing the cells. I carefully fed the film into the automated developer, and ...