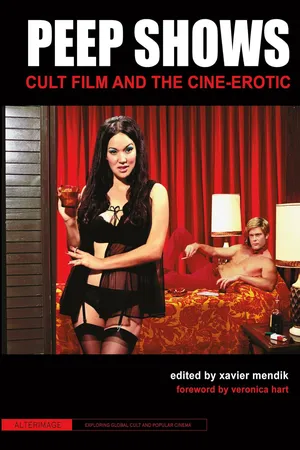

![]()

CHAPTER 1

PAGES OF SIN: BETTIE PAGE – FROM ‘CHEESECAKE’ TEASE TO BONDAGE QUEEN

Bill Osgerby

INTRODUCTION: THE ‘DARK ANGEL’ OF THE 1950S

In Bettie Being Bad, his comic-book homage to Bettie Page, the 1950s pin-up queen, American artist John Workman celebrates the icon’s cult cachet. For Workman, Bettie Page offered a walk on the wild side. Against a tide of bland conventionality, he argues, Page lined up in an army of cultural outlaws who refused to toe the conformist line and instead cocked a defiant snook at the compliant, conservative world of ‘the squares’. Or, as Workman puts it:

In the 1950s, they had Ozzie and Harriet, Davy Crockett and Doris Day. We had Lenny Bruce, E.C. comics and BETTIE PAGE!1

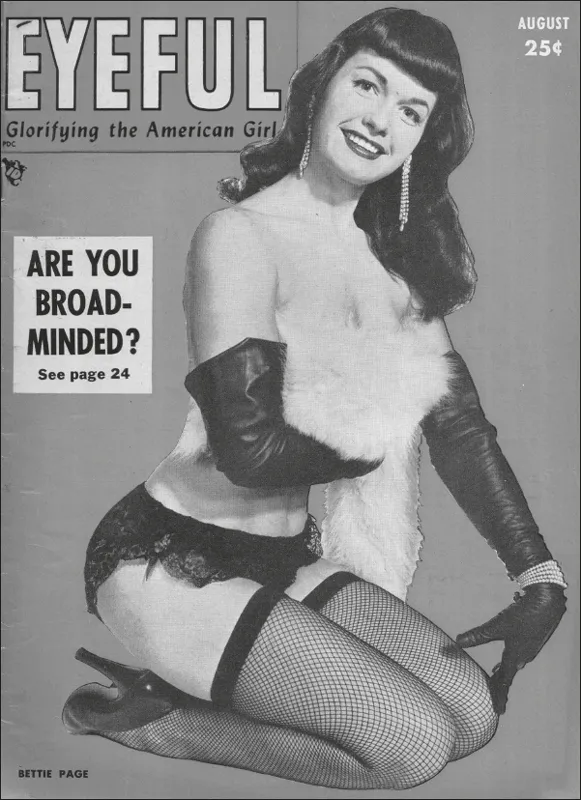

During the 1950s the image of Bettie Page graced the covers of myriad American men’s magazines. Starting her career as a model for amateur camera clubs, Page found fame amid the mid-century boom in pin-up magazine publishing, her trademark raven black hairstyle and beguiling smile captivating a legion of admirers. Tame by modern-day standards, Page’s pin-ups were what the publishing industry called ‘cheesecake’ – photo-spreads of seductively posed (often semi-nude) pretty girls who delighted readers through their winning looks and buxom charms. By the mid-1950s Page had cornered the ‘cheesecake’ market and was omnipresent across the gamut of American men’s magazines, appearing especially regularly in Robert Harrison’s stable of pin-up titles, as well as innumerable film loops and photo-sessions produced by the New York ‘Pin-up King’, Irving Klaw.

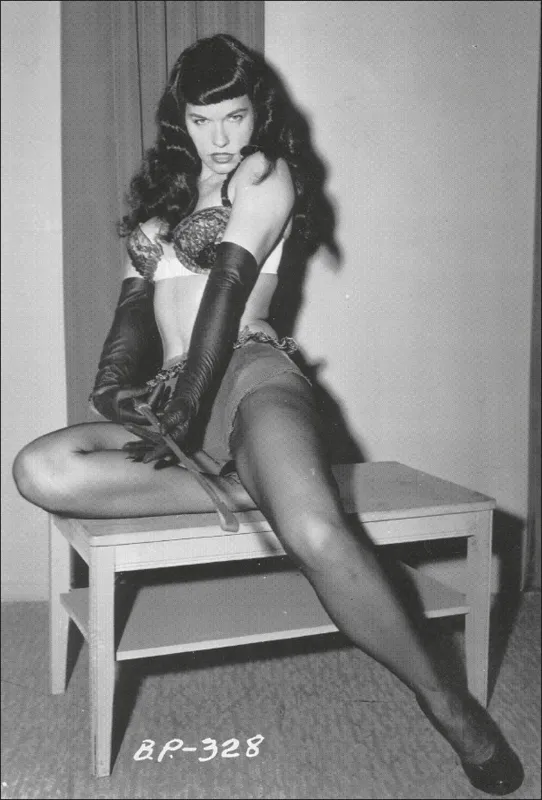

FIGURE 1.1 Bettie Page: the ‘Dark Angel’ of 1950s America

But Bettie Page’s other work with Klaw also helped establish her more infamous reputation as the ‘Dark Angel’ of the 1950s. Page appeared in scores of Klaw’s short films featuring fetish vignettes (depicting ‘cat-fights’, spanking and elaborate bondage sessions), as well as sadomasochistic photo-shoots where Page posed in improbably high-heeled stiletto boots, leather corsets and long-sleeved leather gloves, sometimes brandishing a whip or trussed-up in ropes, chains and a ball-gag.

The sexual dynamics of this facet to Page’s career, however, were always shot-through with polysemic ambiguity. As Maria Buszek argues, rather than being simple exercises in misogyny, the sheer theatricality of Page’s bondage routines can be read as a pantomime of transgressive parody that roguishly revealed the constructed, performative nature of sexual roles and identities:

Even in the … more extreme, intricately constructed bondage scenarios, Page’s participation and performativity shine through as she manages absolutely comical body language through ominous looking binding and ball-gags. Not only does such imagery expose the control and playfulness that Page exerted in her pin-ups, to this day such imagery is held up by many S-M [Sado-Masochism] and B-D [Bondage-Domination] practitioners as exemplary of their belief in role-playing and consent.2

Part of Bettie Page’s cult appeal, therefore, lies in the way her bondage scenes were characterised by a complex plurality that encompassed elements of frisk theatricality. But the way Page oscillated between her ‘good girl’ and ‘bad girl’ imagery is also important. The two sides to Bettie Page’s modelling career make her an enthralling character who has become symbolic of the processes of flux and fragmentation endemic to American public and private life throughout the postwar era. While Page’s ‘cheesecake’ photo-features connoted a bold and buoyant age of playful open-mindedness, her bondage and fetish work was both darker and more mischievous – pointing a sardonic finger at the insecurities and fears lurking behind the confident façade of 1950s America. And it is this plurality and wealth of contradictions that have sustained Bettie Page’s cult status. Indeed, since the 1980s a Bettie Page ‘revival’ has seen the pin-up star enshrined as a popular cultural icon in two biopic movies (Bettie Page: Dark Angel (2004) and The Notorious Bettie Page (2006)), as well as a host of DVD re-releases, comics, fanzines and all manner of popular kitsch. This continuing fascination is indebted to the way Bettie Page functions as a signifier for the tensions of 1950s America, her image combining both the public face of upbeat sparkle and the more private world of guilty secrets.

FIGURE 1.2 Bettie Page as pin-up icon

BURLESQUE BETTIE

Born in Nashville, Tennessee in 1923, Bettie Page (many 1950s magazines misspelled her name as ‘Betty’) grew up in itinerant poverty. Her father, a womanising drunkard, wandered the Depression-hit South in search of work and, after her parents divorced, Bettie spent some time living in an orphanage before settling with her five brothers and sisters and disciplinarian mother. Despite a tough childhood, Page was a hardworking student and, with hopes of becoming a teacher, won a college scholarship and graduated with a degree in Education. Marrying a sailor in 1943, she got a job as a secretary but, after divorcing four years later, she moved to California with the dream of becoming an actress. Modelling work came her way but, despite a handful of screen tests with major studios, a Hollywood career never materialised. Disappointed, Page moved to New York in 1950 and picked up more modelling and secretarial work.3 But things were soon to change.

Wandering along Coney Island beach in autumn 1950, Page got talking with Jerry Tibbs, a black Brooklyn cop and keen amateur photographer. Struck by Page’s looks, Tibbs offered to make her up a portfolio of photographs to hawk around studios and photographers if she agreed to pose for him. The two struck up a friendship, and it was Tibbs who persuaded Page to adopt her trademark hairstyle, suggesting she swap her run-of-the-mill ponytail for a curved fringe (known as ‘bangs’ in America) that would became famous as the classic Bettie Page ‘look’. Through Tibbs and other photographer contacts, Page quickly found work posing on the amateur and semi-professional camera club circuit that had sprung up in America during the 1940s. Ostensibly existing to promote ‘artistic’ photography, many ‘camera clubs’ served as a means of circumventing legal restrictions on the production of nude photos, and Page regularly posed for local clubs on weekend photo jaunts to upstate New York and rural New Jersey.

Page also attracted the attention of pin-up mogul Robert Harrison. During World War II, American pin-up magazines had prospered, partly as a consequence of a general loosening of sexual morality and partly as a result of a burgeoning market among libidinous servicemen.4 Harrison had quickly capitalised on the opportunity, launching his first pin-up title, Beauty Parade, in 1941 and repeating its success with a series of clones – Eyeful (launched in 1942), Wink (1945), Whisper (1946), Titter (1946) and Flirt (1947)

During the early 1950s the pin-up boom continued. Harrison’s attentions, however, were increasingly focusing on the runaway success of his muckraking scandal sheet, Confidential (launched in 1952), but his pin-up titles were still a big earner and in 1951 Bettie Page began gracing their covers and photo-spreads on a regular basis.

In many respects it is easy to see the covers and pictorials of magazines such as Beauty Parade and Eyeful as the embodiment of an oppressive and objectifying ‘male gaze’. But, as Stuart Hall has famously argued, popular culture is invariably an arena characterised by ‘the double movement of containment and resistance’.5 And, in these terms, it is possible to situate Harrison’s pin-up magazines in the long, seditious heritage of American burlesque.

As Robert Allen shows, during the mid-nineteenth century a tradition of theatrical burlesque won popular success through its mixture of impertinent humour and provocative displays of female sensuality. For Allen, burlesque was culturally subversive because it was ‘a physical and ideological inversion of the Victorian ideal of femininity’.6 The scantilyclad burlesque performer, Allen suggests, was a rebellious and self-aware ‘sexual other’ who transgressed norms of ‘proper’ feminine behaviour and appearance by ‘revel[ing] in the display of the female body as a sexed and sensuous object’.7 But, Allen argues, while burlesque initially played to a respectable, middle-class audience, it was quickly relegated to the shadow-world of working-class male leisure. And, in the process, the burlesque performer steadily ‘lost’ her voice. As burlesque increasingly revolved around the display of the performer’s body, Allen contends, ‘her transgressive power was circumscribed by her construction as an exotic other removed from the world of ordinary women’.8

Allen’s account, however, is too hasty in announcing the demise of burlesque’s subversive potential. During the 1950s, for example, echoes of burlesque’s tradition of transgression still reverberated through American popular culture. For instance, while Robert Harrison’s pinup magazines certainly presented pin-up models as sexual objects, they also featured marked elements of camp humour and playful satire. Many of Harrison’s photo-spreads, for example, featured models acting out spoof scenarios in elaborate ‘comic book’-style photo stories whose tongue-in-cheek silliness effectively elaborated a self-parody of the whole pin-up genre. ‘Gal and a Gorilla’, for instance, saw Bettie Page zipping around New York with her ‘constant escort’, the scooter-riding Gus – a man dressed in a ludicrous gorilla costume.9

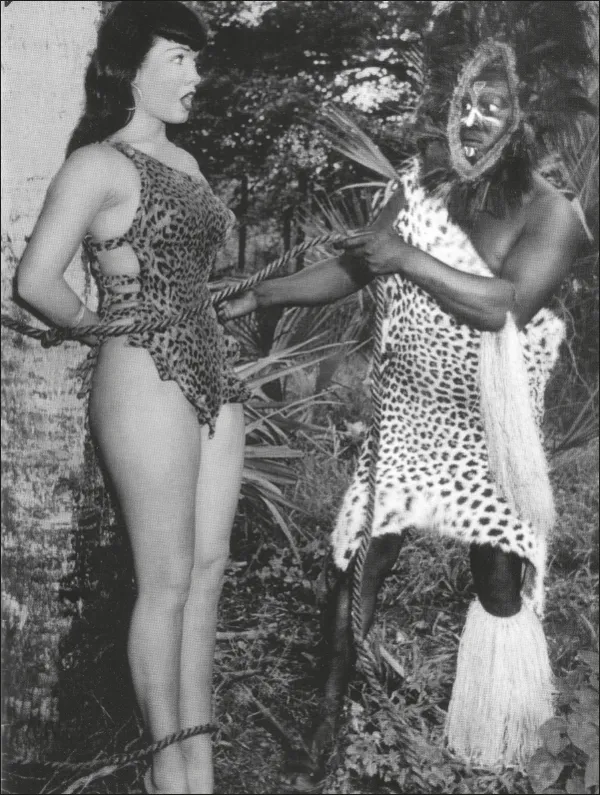

And the burlesque resonated through many other aspects of Bettie Page’s career. Her work with photographer Bunny Yaeger, for instance, undoubtedly traded on Page’s knockout looks, but it was also marked by a knowing sense of irony. Yaeger had, herself, been a successful pin-up model and was trying to get her foot in the door as a photographer when she teamed up with Page in 1954. In Florida the pair spent a month working on some of Page’s most successful photo-shoots. One of the most famous was the ‘Jungle Bettie’ session that took place at the USA Africa Wildlife Park. Clad in a spectacular leopard-skin outfit (that, like most of her costumes, she had made herself), Page posed with a pair of leashed cheetahs, swung like Tarzan from lush mango trees and was captured by a tribe of cannibals in a series of photographs that at once both celebrated and playfully lampooned stock stereotypes of the ‘exotic Amazon’.

Another light-hearted Yaeger shoot saw Bettie posing nude, aside from a jolly Santa Claus hat and a cheeky wink given to the camera – an image that was quickly snapped up by Hugh Hefner and used as the centrefold to the January 1955 edition of his flourishing Playboy magazine.

Burlesque traits also surfaced in Page’s work with Irving Klaw. It was through her work with Robert Harrison that Page first got to know Klaw and his sister Paula. The Klaws had started in business during the 1930s, running a second-hand bookstore in Manhattan, with a sideline in mail order magic tricks. Neither trade was exactly a money-spinner. But in 1941 they struck lucky when Irving noticed his customers’ annoying habit of ripping-out pictures of movie stars from his magazine stock. Spotting a market opportunity, the Klaws went into business selling movie posters and publicity stills. Abandoning the magic tricks, they set up a new company – Movie Star News – and did a brisk trade in mail order sales of movie material. During the war the Klaws enjoyed a lucrative turnover selling pictures of Rita Hayworth and Betty Grable to GIs posted overseas, but during the 1950s they moved into producing their own pin-ups of hired models, working with Bettie Page for the first time in 1952.10 But, as well as the photo-shoots, Irving Klaw also had big screen ambitions.

FIGURE 1.3 ‘Jungle Bettie’: stereotypes of sexuality and race are parodied in Page’s work with Bunny Yaeger

FIGURE 1.4 Burlesque goes celluloid: Bettie Page in the influential Teaserama

Klaw, however, was beaten to the post by Martin Lewis. A New York cinema owner an...