![]()

1

AID DEPENDENCE AND QUALITY OF GOVERNANCE

Global Evidence and the Case of Cambodia

FOREIGN AID HAS the potential to contribute to good governance in several ways. To the extent that aid is conditioned on government actions to improve governance, it can produce positive change. If aid encompasses technical cooperation focused on elements of good governance, it can also induce reform. And, more generally, if aid succeeds in increasing per capita income and human development, it can afford and enable good governance.1 Research based on cross-sectional data examining limited dimensions of governance suggests, however, that dependence on foreign aid can undermine institutional quality, weaken accountability, encourage rent-seeking and corruption, foment conflict over control of aid funds, siphon off scarce talent from the public sector to the aid industry, and alleviate pressures to reform inefficient policies and institutions (Knack 2001:310).

This chapter seeks to answer the question of whether foreign aid worsens governance on two levels. First, it summarizes my examination of the relationship between aid and governance in more than two hundred countries and territories. Second, it considers the case of Cambodia, investigating the governance consequences of Cambodia’s aid dependence since 1993.

Cambodia makes an interesting case study of the effects of aid dependence, in part because it had little choice in whether to engage donors or, in a wider sense, how to relate to the overall global political economy. The country was a pariah state for the duration of the 1980s in the aftermath of the Khmer Rouge period and the invasion by Vietnam, and it fervently sought to establish normalized international relations and acceptance. Following the Cold War, the Paris Peace Agreement signed on October 23, 1991, signaled the cessation of open warfare in Cambodia, although not the end of conflict itself. After the country’s $1.5 billion United Nations (UN)-organized elections in 1993, Cambodia received $5 billion in official development assistance (ODA),2 turning it into one of the most aid-dependent countries in the world, with net ODA received equivalent to 94.3 percent of central government spending between 2002 and 2010.

Cambodia’s lack of choice has not been without consequences, however. Although aid dependence seems to have only limited negative effects in the aggregate, it creates significant distortions in the Cambodian political economy, with predictably bad consequences for the nation’s governance.

Does Foreign Aid Worsen Governance?

Foreign aid has long been justified as essential for development in countries in which investment is missing, and aid helps complete missing or imperfect markets.3 Peter Boone was the first to consider, empirically, a country’s political system in determining aid effectiveness. He found that aid neither significantly increases investment nor benefits the poor as measured by improvements in human development indicators—but it does increase the size of government. According to Boone, “Poverty is not caused by capital shortage, and it is not optimal for politicians to adjust distortionary policies when they receive aid flows” (1996:322).

Boone’s study is credited with having singlehandedly motivated World Bank economists Craig Burnside and David Dollar to perform their own analysis in an attempt to rescue aid from policy irrelevance. Burnside and Dollar (1997) substituted Boone’s political system proxy with a quality-of-policy proxy and found that money matters in a good policy environment. In their study of the relationships among aid, policies, and growth in fifty-six countries over six four-year periods, they demonstrated that a linear relationship exists between the quality of governance and development outcome and that aid spurs growth and poverty reduction only in a good policy environment. In the presence of poor policies, aid has no positive effect on growth. For example, under weak economic management in developing countries, there is no relationship between aid and change in infant mortality, but in countries where economic management is stronger, there is a favorable relationship.

However, subsequent scrutiny of Burnside and Dollar’s analysis has revealed a number of weaknesses. Several scholars have noted that the addition of another four-year period (1994–1997) and some more recent observations to Burnside and Dollar’s data set changes the results (Harms and Lutz 2004:20). Henrik Hansen and Finn Tarp (2000) argued that Burnside and Dollar’s findings were the result of diminishing returns to aid. Analyzing the same set of countries and using the same basic model specification, they concluded that aid does have a positive impact on growth even in countries with a poor policy environment. In a veiled reference to the World Bank’s 1998 study Assessing Aid: What Works, What Doesn’t, and Why, Hansen and Tarp maintained that “the unresolved issue in assessing aid effectiveness is not whether aid works, but how and whether we can make the different kinds of aid instruments at hand work better in varying country circumstances” (2000:394).

Beyond questions of aid effectiveness, concerns emerged that aid dependence degrades the quality of governance. Bräutigam and Botchwey (1999) used data for thirty-one African countries from 1990 to argue that preexisting quality of governance determined the extent to which aid undermines institutions (cited in Knack 2001:314n5). Jakob Svensson (2000) found that, when instrumented with income, terms of trade, and population size, aid expectation increases graft in ethnically fractionalized countries. Using geographic and cultural proximity as instrumental variables for aid, on the other hand, José Tavares (2003) countered that aid does not corrupt. For those who believe in the intrinsic differences in countries, Tavares’s method is more appealing.

Discussing empirical findings that aid dependence is associated with corruption—only one of several elements of governance—Paul Collier and David Dollar note that aid changes the relative price of good versus bad governance, making it cheaper and more likely that the former will be substituted for the latter. On the other hand, aid also “directly augments public resources and reduces the need for the government to fund its expenditures through taxation, thereby reducing domestic pressure for accountability” (2004:F263). They conclude that the “net effect” of aid on corruption and thus governance “could be favourable or unfavourable, the question only being resolvable empirically” (F263). Arthur Goldsmith, too, notes that “more work clearly needs to be done to ascertain the extent to which aid has a destructive effect on the state” (2001:128).

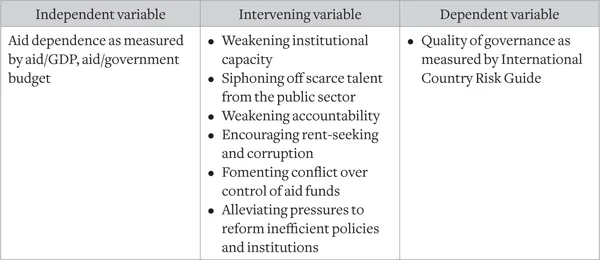

The cross-sectional analysis performed by Stephen Knack (2001) finds a negative relationship between aid dependence and quality of governance. According to Knack, aid dependence hurts governance by weakening institutional capacity, siphoning off scarce talent from the bureaucracy, undermining accountability, encouraging rent-seeking and corruption, fomenting conflict over control of aid funds, and alleviating pressures to reform inefficient policies and institutions (see table 1.1). The implication is that, through intervening variables, aid dependence causes the quality of governance to worsen over time. Drawing on the Freedom House Index in a more recent empirical study, Knack (2004) finds that little if any of the progress toward democratization between 1975 and 1996 can be attributed to foreign aid. Heckelman and Knack (2005), using Economic Freedom data (and its components) as their dependent variable, find that aid harms market-liberalizing reform.

Table 1.1 The more aid-dependent a country, the lower the quality of governance

Source: Adapted from Knack (2001:310).

If verified, Knack’s 2001 findings would pose a serious problem for international development. The drive by international financial institutions to assess aid itself (and to pin the blame for its ineffectiveness on poor governance) suggests that they have long since perceived this problem and begun to take stock in an act of self-preservation. Worldwide aid levels tumbled after peaking in 1992. The World Bank was moved to appeal directly to donor countries to essentially hang in there and continue funding. Its Assessing Aid report (1998) found that the impact of aid on growth and infant mortality depends on “sound economic management,” as measured by an index of economic policies and institutional quality. If good governance is needed for aid to work effectively but aid dependence leads to bad governance, then where does that leave developing countries and the donors trying to help them?

Few would deny that aid dependence can have a pernicious effect on governance. What remains subject to debate is the significance of this effect and which dimensions of governance are affected. Knack’s three studies all use cross-sectional analysis, which does not control for potentially omitted variables affecting both aid flows and changes in governance; moreover, Knack’s choice of instrumental variables for aid—a statistical procedure that counteracts endogeneity in aid—is at best imperfect. Aid could be endogenous if donors systematically disbursed more or less resources to those countries that had good or bad governance as a reward or punishment.4 Knack concedes this potential, noting that “aid … [could] reflect endogeneity bias: if donors direct aid toward countries experiencing deteriorations in the quality of governance, OLS [Ordinary Least Squares] estimates will overstate the adverse impact of aid on governance” (2001:319). Knack’s solution is to engage nearly identical exogenous instruments to those used by Burnside and Dollar (1997, 2000)—infant mortality in 1980 and (log of) initial gross domestic product (GDP) per capita as indicators of recipient need, along with initial population (log), a Franc zone dummy, and a Central America dummy as measures of donor interest.5 A good instrumental variable is one that is highly correlated with the regressor—aid—but is uncorrelated (except through aid) with the dependent variable—governance. Knack cites infant mortality as “easily the most important predictor of aid” (2000:14), and his Southern Economic Journal article drawn from his working paper adds population and per capita income as “the most significant predictors of aid” (2001:319). Although unelaborated beyond “good indicator of recipient need,” the presumed logic of this instrument is that infant mortality is a basis for why aid is given regardless of governance. Of course, infant mortality is unlikely to be purely exogenous—it is likely affected by poor governance, although in the long term it is unlikely to affect governance.

Derek Headey argues eloquently against the use of instruments for aid—which he calls “fundamentally flawed in ways which are largely ignored by the literature to date”—in favor of using lagged aid only to control for endogeneity (2005:4–5). He concludes, “Lagging aid means that we are more likely to test the effects of aid over the medium term, which is probably all the data are capable of doing” (13). In Ear (2007a), I followed a similar design, repeating Knack’s use of infant mortality as an instrumental variable for aid, but with the above caveat and the introduction of a lag in aid. Beyond this, I used a more extensive data set. From 2005, it covers 209 countries and territories for five specific years: 1996, 1998, 2000, 2002, and 2004. The data assign up to 352 individual measures of governance to categories that capture key dimensions of governance. I also introduced pooled time-series cross-sectional (TSCS) analysis with fixed effect to control for potential omitted variable bias, and I examined different elements of aid. I reported both instrumented and uninstrumented findings and showed that they are generally consistent.

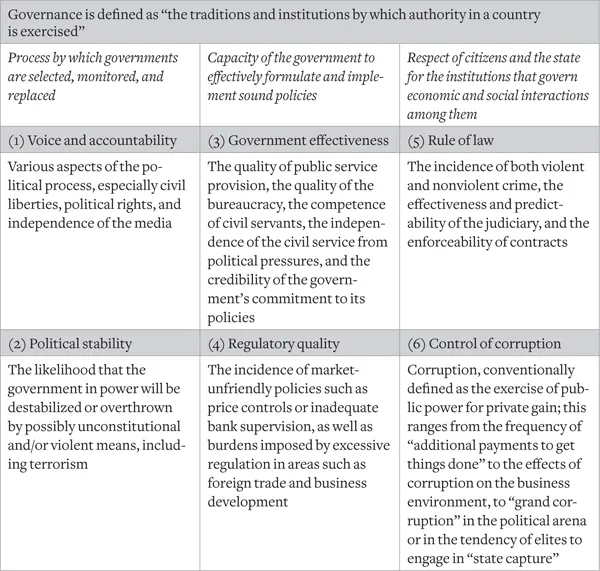

Table 1.2 Six dimensions of governance

Source: Adapted from Kaufmann, Kraay, and Zoido-Lobatón (1999).

The data rely upon the work of Daniel Kaufmann, Aart Kraay, and Pablo Zoido-Lobatón (1999) in identifying and defining six dimensions of governance, whose work has grown in aggregation in the past decade. This book uses the 2005 version. Hence, the definition of governance used in this book is also the definition Kaufmann et al. use: “governance [is] the traditions and institutions by which authority in a country is exercised” (see table 1.2). The first two dimensions speak to the processes of government selection, monitoring, and replacement: “Voice and accountability” describe the openness and responsiveness of a government to civil society and encompass the protection of civil liberties and political rights, as well as media independence. “Political stability” captures how likely a government is to be destabilized or overthrown by unconstitutional or violent means.6 The second two dimensions indicate the extent to which a government is able to create and implement sound policies effectively: “government effectiveness” considers government commitment to its policies, the quality of a government’s public services and its bureaucracy, and whether it has a competent and independent civil service; “regulatory quality” concerns the extent of market-unfriendly regulation, such as price controls or inadequate bank supervision, and the extent to which such regulations may have negative effects on foreign trade and economic development. The final two dimensions of governance involve citizens’ attitudes toward the institutions of the state: “rule of law” measures the government’s effectiveness in preventing crime, enforcing contracts, and maintaining an effective and predictable judiciary; “control of corruption” describes government success in curbing corruption, defined as “the exercise of public power for private gain” (Kaufmann et al. 2005:4), which ranges from demands for “additional payments to get things done” (66) to the distortion of the business environment to grand corruption in the political arena or in the tendency of elites to engage in state capture (5).

Since quality of governance is rooted in several determinants, among them income, population, and other invariant factors such as culture and history, no one would suggest that aid alone determines the quality of governance in developing countries. Instead, I examined four hypotheses:

1. Aid dependence worsens governance.

2. Different dimensions of governance respond to aid differently.

3. Disaggregating aid into technical cooperation and average grant element (both components of aid) results in different effects on governance.

4. Knack’s findings overstate the negative impact of aid dependence on governance.

Regarding the first hypothesis, I found that aid dependence is statistically significant as an explanatory variable that negatively affects various dimensions of governance, whether instrumented or not, under cross-sectional analysis. When I applied a more sophisticated method of analysis to the second hypothesis, it was only partly proven; I found that the rule of law is the only dimension of governance hurt by aid dependence. Third, I found that two important components of aid, technical cooperation and average grant element, have statistically significant effects when considered with aid—both aid and technical cooperation hurt the rule of law. However, grants and aid help voice and accountability. Finally, regarding the fourth hypothesis, I concluded that Knack’s findings do overstate the negative impact of aid dependence on governance. The findings were first reported and elaborated at length in Ear (2007a), an article that won the June Pallot Award for best article published that year in the International Public Management Journal, which, as of 2010, had an impact factor of 1.949 and ranks third out of thirty-nine public administration journals.

Knack may have been too pessimistic when he concluded that “higher aid levels erode the quality of governance, as measured by indexes of bureaucratic quality, corruption, and the rule of law” (2001:310), and later when with Jac Heckelman he wrote that “aid on balance significantly retards rather than encourages market-oriented policy reform” (2005:1). Under pooled TSCS, aid dependence explains very little of the variation observed in different dimensions of governance. It may be that the finding of a less prevalent negative effect than Knack reported is due to the attempts of the World Bank and other multilateral donors, beginning in the late 1990s, to use aid to positively affect governance, since Knack covered the period 1982–1995.

Nonethe...