![]()

Part I

Premodern Vietnam

![]()

Chapter 1

THE PERIOD OF NORTHERN EMPIRE

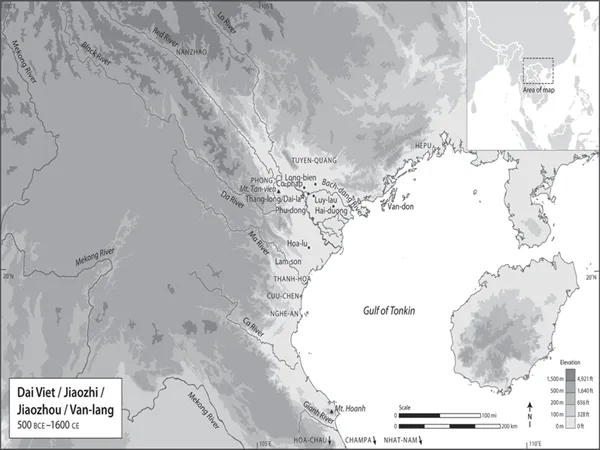

The region of what is today north and north-central Vietnam entered the historical record as the Northern empire of the Qin (255–207 B.C.E.) expanded to the south into the land of the Yue (the Shanghai region and south). The rapid collapse of the Qin left a warlord family, the Zhao (V: Trieu), in control of what are now Guangdong and northern Vietnam (then referred to as Nan Yue [Southern Yue]; V: Nam Viet). From the beginning, the Qin forces met local armed resistance in a pattern that was periodically repeated throughout the centuries. What we now call guerrilla warfare originated in peripheral localities to contest the distant northern power.

When the Han dynasty took power in the North, the Zhao resisted its efforts at Southern control until their fall in 111 B.C.E. For the next century and a half, Han authority over the indigenous lords was loose and relatively unobtrusive. Despite greater contact with Northern influences, local society and culture remained the same. But when Wang Mang usurped power (9–25 C.E.) in the North, Northern refugees fled to the South, expanding the Sinic presence there. Led by the aristocratic Trung sisters, Nhac and Nhi, indigenous resisters drove out the Northern forces and kept them at bay for three years (40–42). The Han then sent General Ma Yuan to suppress the resistance. Establishing the Northern administrative system in the central Red River Delta, the general set the stage for almost nine centuries of Northern domination, during which Chinese power periodically waxed and waned.

During this time, there was a constant blending of incoming Northern families with the indigenous population, amid a growing sense of South and North, the local region and a more remote China proper. Besides the many Northern officials, merchants, and others who came south, carried out their business, and then returned north, some settled permanently in the South and adopted its way of life. Both groups brought with them their social, cultural, and intellectual habits and gradually began to remake the indigenous society. The Northerners had specific ideas about how to govern, via the prefecture/district system, and sought to apply them to their new homeland. The local economy was based on wet-rice agriculture, but it was the trade in exotic goods from the mountains and the seas as well as from the lands beyond them that attracted the Northerners, as explained by the Northern official Chen Shou’s observations in “Riches of the South.”

Others who came to Vietnam’s Red River Delta during the first millennium C.E. arrived on the trade and communication routes stretching from the coastal Chinese seas all the way to the Middle East and the Mediterranean. Various merchants, monks, and travelers—Buddhist, Indian, Central Asian, and Arab—passed through the region’s ports, bringing with them goods from their home regions, which stimulated local production and increased local wealth. In particular, Buddhists on the grand tour (India, Southeast Asia, China, Central Asia) entered the Red River Delta with their beliefs, texts, and need for temples and monasteries. Through these centuries, Buddhism increasingly permeated local society, especially in the central area of the Red River Delta, and its presence was noted by contemporary observers, including Tan Qian (“Buddhism in the South”), who wrote at the end of the fifth century, and Shen Quanqi (“Buddhism as It Existed in the South”), who wrote in the eighth century. Buddhism also served as a link to other societies, such as those in Champa (central Vietnam) and Srivijaya (southeast Sumatra) to the south, as well as to their Northern compatriots.

A variety of cultures thus took root across the Vietnamese lowlands, coast, and highlands. Locally diverse indigenous beliefs (such as those represented in the spirit cults), the standard Northern culture of the elite, the strong transnational Buddhist presence, and other ethnic patterns in the mountains and along the coast were included in the mix. During times of Northern political weakness, local patterns reasserted themselves and competed for dominance. In both the sixth and the tenth centuries, local chieftains used aspects of Northern rule, indigenous myth, and Buddhist claims of legitimacy to challenge Northern political control. Although the Sui and Tang dynasties were able to crush the first such effort at local autonomy in the sixth century, the Song dynasty was unable (or unwilling) to suppress the second effort in the tenth century.

From the seventh to the tenth century, forces outside the realm of Northern control vied in challenging it. To the south, Champa continuously raided up the coast, competing politically and economically with the Chinese territory. To the west, Nanzhao (in what is now Yunnan), on the southwestern fringe of the Tang empire, posed a threat down the Red River. Tai chieftains in the western and northern mountains sometimes allied with Nanzhao, and their political and economic relations with the lowlanders occasionally caused tensions. Throughout the eighth and ninth centuries, both coastal raiders from Champa and the islands of Southeast Asia and a strong Nanzhao and Tai invasion helped weaken the Tang’s hold on this Southern territory.

Overall, the first millennium C.E. was a highly dynamic and transformative period for northern Vietnam. The indigenous society was stimulated externally by political, social, economic, religious, and cultural forces, and it responded by absorbing many of these elements into its own culture. A number of patterns for Vietnam in later periods were set during these centuries: the use of Chinese characters in writing, chopsticks for eating, money in the form of Chinese copper cash, and the Tang dynasty’s poetry and laws. Nonetheless, the emerging Vietnamese polity did not become a replica of the Northern state, as the Vietnamese blended these internal and external influences to form their own style.

THE LAND

CHEN SHOU

SOUTH AND NORTH (297)

Shi Xie (V: Si Nhiep or Si Vuong [King Si]) was a local strongman of Northern descent in Jiaozhou/Jiaozhi (northern Vietnam) at the end of the Han dynasty (206 B.C.E.–220 C.E.). The following excerpt from his biography in the Chronicle of the Wu Dynasty, one of the books in Chen Shou’s Chronicle of the Three Kingdoms, describes both the increasing chaos as the Han dynasty weakened and the sense of distance between this Southern border region and the capital far to the North. Such distance enabled the political mischief described here and a local family like the Shi to gain control in the South.

Xie’s younger brother Shi Wu took sick and died first. After the death of Zhu Fu, the Han appointed Zhang Jin as Inspector of Jiaozhou. Jin was later assassinated by his own general, Qu Jing. Subsequently, the Governor of Jingzhou, Liu Biao, appointed Lai Gong from Lingling as Jin’s replacement. At about the same time, the Grand Administrator of Cangwu, Shi Huang, passed away. Biao thereupon appointed Wu Ju to take his place. Along with Gong, he arrived to fill his post. The Han court, having learned of the death of Zhang Jin, sent an imperial proclamation to Xie, saying, “Jiaozhou is a very distant region, so far beyond the rivers and seas to the south, a place where our beneficence can barely reach and whence the gratitude of the people can hardly flow back. It has come to our attention that the rebellious Liu Biao, viceroy of Zhang province directly to the north, has had the effrontery to have appointed Lai Gong to office and that he has his ambitious eye on our southern lands. Thus we now charge you to become our General of the Gentlemen of the Household Who Comforts the South, in charge of all seven commanderies, maintaining as before your authority as Grand Administrator of Jiaozhi.”

[Wu zhi, 4, in Chen Shu, San guo zhi (hereafter, SGZ); trans. O’Harrow, “Men of Hu,” 262]

SHEN QUANQI

LIFE IN THE SOUTH (EARLY EIGHTH CENTURY)

By the early eighth century, the Southern region had been fully absorbed into the great cosmopolitan Tang dynasty as the Protectorate of Annan (V: Annam). In the following poem, the poet Shen Quanqi describes a Northerner’s sense of living and growing old in the South. He evokes a sense of both space and time, the past and its power, as represented by the spirits of the warlord Zhao Tuo (V: Trieu Da [second century B.C.E.]) and the local ruler, Shi Xie. Commissioner Tuo later became known as the king of Nan Yue (V: Nam Viet). This poem was included in the Short Record of Annan (1333), compiled by Le Tac, a Vietnamese living in China.

I have heard it said of Jiaozhi

That southern habits penetrate one’s heart.

Winter’s portion is brief;

Three seasons are partial to a brightly wheeling sun.

Here Commissioner Tuo obtained a kingdom;

Shi Xie has long been roaming the nether world.

Village dwellings have been handed down through generations;

Fish and salt have been produced since ancient times.

In remote ages, the people of Yue [V: Viet] sent pheasants as tribute;

The Han dynasty general pondered the sparrowhawk.

The Northern Dipper hangs over Mount Chong;

The south wind pulls at the Zhang Sea.

Since I last left home, the months have swiftly come and gone;

My hairline shows that I have grown old.

My elder and younger brothers have yielded to their fates;

My wife and children have departed to reap their destinies.

An empty path, a ruined wall, tears;

It is clear that my heart has not echoed Heaven’s will.

[Le Tac, An Nam chi luoc (hereafter, ANCL), 157; trans. Taylor, Birth of Vietnam, 185–86]

ZENG GUN

THE SPIRIT CAO LO (NINTH CENTURY)

Following the victory in the 860s over invaders from Nanzhao (present-day Yunnan) to the west, Gao Pian (V: Cao Bien or Cao Vuong [King Cao]), the Northern general stationed in the Protectorate of Annan (V: Annam, earlier known as Jiaozhi), was believed to have encountered the local spiritual power of the land. This was recounted in a document from the South written by a Northern official and later recorded in Departed Spirits of the Viet Realm (1329), a collection of cultic tales by Ly Te Xuyen. “The Spirit Cao Lo” describes the spirit world as viewed locally as well as Gao’s view of the land’s beauty. The so-called Dragon’s Belly is an area in the center of the Red River Delta around the present-day Hanoi where Gao Pian established his capital of Dai La (Great Walled City).

Determinably Bold, Unyieldingly Orthodox, Majestically Gracious King

According to the Records of Jiaozhi as cited in Do Thien’s History, the King was named Cao Lo and was a meritorious subordinate of King An Duong [r. 257?–179 B.C.E.].1 He was commonly called Commander Lo or the Rock S...