- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

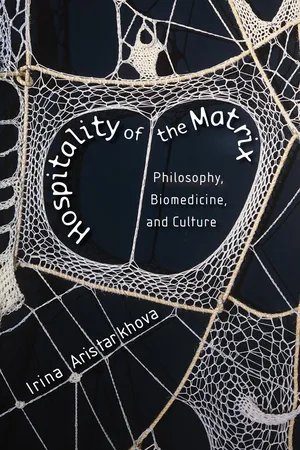

The question "Where do we come from?" has fascinated philosophers, scientists, and artists for generations. This book reorients the question of the matrix as a place where everything comes from (chora, womb, incubator) by recasting it in terms of acts of "matrixial/maternal hospitality" producing space and matter of and for the other. Irina Aristarkhova theorizes such hospitality with the potential to go beyond tolerance in understanding self/other relations. Building on and critically evaluating a wide range of historical and contemporary scholarship, she applies this theoretical framework to the science, technology, and art of ectogenesis (artificial womb, neonatal incubators, and other types of generation outside of the maternal body) and proves the question "Can the machine nurse?" is critical when approaching and understanding the functional capacities and failures of incubating technologies, such as artificial placenta. Aristarkhova concludes with the science and art of male pregnancy, positioning the condition as a question of the hospitable man and newly defined fatherhood and its challenge to the conception of masculinity as unable to welcome the other.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

PhilosophySubtopic

Biotechnology in Medicine1

Journeys of the Matrix

In and Out of the Maternal Body

This chapter explores a simple question, “What is the matrix?” The term matrix and questions about it came to the forefront of popular culture in the late 1990s, when the movie The Matrix became a global box office success and a cultural phenomenon. Today the notion of the matrix is variously employed to mean “an array of numbers,” “mold,” “virtual reality,” and a “symbolic order that structures reality for us.” However, though this term also meant “the womb” and “mother” for a significant portion of its existence (even as late as the end of the nineteenth century), this relationship to the womb and the maternal body is almost completely absent in most contemporary uses of matrix. This curious but oft-neglected connection between the maternal body and the term matrix as it is employed (or not) in philosophy, art, and biomedicine has been the subject of my research for a while now (Aristarkhova 2002, 2006). In the course of this research, I have increasingly come to realize that what is at stake here is not so much to establish what the matrix really is (i.e., about arriving at a particular definition, “better” as it might seem to be), but to understand what an expanded formulation of the matrix, one that includes this relationship to the womb and the maternal body, does: what it enables and produces in terms of our experiences of space and embodiment, especially with regard to the technological and cultural imaginaries of reproduction. This project of recovering the maternal from/in the matrix is not an etymological curiosity, but one of cultural urgency insofar as the question of how one imagines and therefore inhabits space and embodiment (maternal or not) with others will continue to remain a critical sociopolitical challenge. What is also at stake here, therefore, is our definition of space and the role that a reintroduction of the maternal connection to the matrix plays in producing a different conception of space. In the next chapter, through the concept of hospitality, I specifically examine the ethical potential of enabling a different relationship to others that is embodied in this reformulation of the matrix.

The Meanings of Matrix

The etymology of matrix, with its connection to the root words for matter and mother, reveals the term’s direct relation to the maternal body and its originating role as the source of being and becoming. This early connection to the maternal body was transformed in modern usages of the word, especially after the English mathematician J. J. Sylvester, in the middle of the nineteenth century, used the term matrix to name an enclosed array of numbers. This section traces the remarkable persistence of the notion of the matrix, especially as it has been captured and circulated within the contemporary imagination at this moment in history and its proliferation from highly discipline-specific deployments (e.g., in geology or molecular biology) to popular culture (e.g., the car Toyota Matrix or the movie The Matrix).

Thus, the word matrix needs to be analyzed with reference to the old semantic triad of matter, mother, and matrix. If we imagine a simplified map of meanings as a series of concentric circles, the matrix is within the mother, and the mother is within the matter. In most Indo-European languages today the most common word for the womb is not matrix but uterus (in biomedical usages). Moreover, unlike its synonyms—womb and uterus —the word matrix has been used in relation to any type of matter (plant, animal, geological, imaginary, etc).1 The matrix’s simultaneous relation to and dissociation from the maternal body, the womb, and pregnancy enable its powerful return in a multiplicity of discourses.

Matrix, an Indo-European word, is formed from the root mater, “mother” (and thus is related to the word material, “matter”). In Latin the suffix trix refers to a “productive feminine agent” (Baldi 2002:302). Its meaning is related to genetrix, meaning then a biological mother, and nutrix, a female nurse, as well as a Roman slave (Ernout and Meillet 1932:565). The suffix (“productive feminine agent”) embodies the very referent of productivity, making a connection between the feminine (symbolic) and maternal agency.2 The matrix’s relation to generativity via nursing is also noteworthy and will be explored further in the second section of this chapter with reference to the concept of chora.

Early Latin (before the first century ce) meanings of matrix indicated a female animal kept for breeding or a pregnant animal. It could also mean a “parent plant.” Its most general early meaning was the “source and origin” (a birthplace or, understood more generally, a place of generation). Matrix was not used widely to mean either “womb” (especially the human womb) or “original place.” Uterus was the standard term for “womb” in Latin, while chora was a privileged, maternally inspired term used in ancient philosophy to ponder the nature of space and place. The first use of the matrix as “womb,” detailed by J. N. Adams in his Latin Sexual Vocabulary, occurs in Seneca the Elder’s Controversiae, written around the very beginning of the first millennium ce: “she no longer pleases her husband as [the matrix, womb] breeder” (Adams 1982:105). Here, it seems, that the old meaning of the “breeding animal” is mobilized to make the first known usage of the matrix as the womb. It refers to pregnancy indirectly, by inference from a heterosexual relationship. Adams suggests that this transitory meaning personifies the womb and could be seen as an “ambiguous,” and nascent use of the term. The establishment of matrix as “womb” in Late Latin partially relies on the close semantic relation between mother, breeder, and womb; these words were often used interchangeably (Adams 1982:106). This shows how the early relation between matter, mother, and womb remained in the use of the matrix long after it stopped meaning “the breeding animal” or “parent plant.” After its meaning of “womb” became established, matrix was used widely in Late Latin medical literature. Adams documents its usage as “womb” in Theodorus Priscianus’s writings on gynecology (circa 400 ce), replacing other words for womb, including uterus. In general, he concludes that “it is a fair assumption that the great frequency of matrix in late medical works considered as a whole reflects its wide currency at the time” (Adams 1982:107).

Thereafter, the word primarily survived through a rather narrow usage in printing and casting, meaning a mold employed in the production of various relief surfaces. Even though some etymological dictionaries (The Compact Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary, 1981, 1744) indicate that between the fourteenth and seventeenth centuries it was also used as “place or medium where something is developed” (around 1555) and “embedding or enclosing mass” (1641), these usages were rare. Although matrix was still used to designate “womb” in 1526 (in biblical translations into English, Tyndale, 1837 [1526]:26), uterus became a much more common term for “womb” in the newly established disciplines promulgated under the rubric of “generation” study: as an organ (muscle tissue) where off spring develops.3 Since the nineteenth century, matrix has become increasingly framed as a productive and generative site in thinking about space, while uterus seems to have been permanently defined in the negative: as a “place” of suffering and all kinds of other “problems.”4

Judging by the previous examples, matrix in English oscillated between being a space from which things and beings originate and a mold for printing and casting. It is important to note that until recently it has maintained its reference to the maternal body in some other Indo-European languages. In modern times, however, its meaning of “womb” even in Romance languages (matrice) was overtaken by other meanings—such as mold and imprint bearer—making the old references to “womb,” “breeding animal,” “parent plant,” and, to a lesser extent, “the origin/source” archaic or altogether defunct.5 The matrix could easily have continued to be an unexciting “mold for casting” and obscure “origin” to the general public, popular science, modern art, and philosophy if not for J. J. Sylvester. In 1850 Sylvester suggested the use of the term matrix for a novel development in mathematics. It was here, in mathematics, that we see the modern revival of the matrix. Since then we have observed the word’s proliferation and permutation in multiple contexts, while its connection to the womb has become archaic and outdated or even completely forgotten, as in the definition from the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary to follow. While Sylvester himself borrowed the term directly from its etymological meaning of “womb,” and not from the world of casting and printing terminology, he applied it to the most abstract conception of mathematical thought. Karen Hunger Parshall writes in her biography of the mathematician that the first times Sylvester used the term matrix were in passing in November 1850 and in a published paper from 1851. He introduced it with this revealing explanation: matrix is “a rectangular array of terms, out of which different systems of determinants may be engendered, as from the womb of a common parent” (Sylvester, quoted in Parshall 2006:102). In line with my argument about the “generative” and “supporting/forming” potential of the matrix as the main impetus for its current usages, Parshall notes that Sylvester saw “unlimited possibilities” “in the matrix as the underlying structure and in the determinant as a key construct based on it” (Parshall 2006:102). Moreover, Sylvester considered naming to be a very important act in moving mathematics forward and thus paid a lot of attention to it. He even claimed himself be a “Mathematical Adam” (2006:111). Parshall suggests that he was aligning himself with “those who give birth to new lives” and therefore “have the privilege of naming their off spring and, in so doing, of establishing their patronage” (2006:111).

For the first time, Sylvester connected the symbolic realm of the matrix as a “generative space” with the applied realm of the matrix as a “mold” in casting and printing. For Sylvester, the matrix was a container and a thing like a womb. His leap occurred through the introduction of a “common parent,” replacing the mother with an abstract substitute through this “common” claim to the womb. Intrinsic to Sylvester’s choice of the term matrix is a hope that the new mathematical entity he (with others) was working on would be as “generative” as the womb. This mathematical nomenclature is enacted as a classic metaphorical operation—it mines the semantic associations with the womb and the maternal even while distancing its meanings from the maternal body. One could argue that all usages of matrix issuing from this particular semantic appropriation can operate as metaphors only insofar as they are “not” the womb, thus enabling the amnesia of its meaning as the “womb” in all its current cultural appropriations.6 In the twentieth century the matrix has become a catchall term to designate things, numbers, ideas, and phenomena, connected, if at all, only by a faint memory to a spatial, voluminous, stretchable “something.” The main quality of that entity is its ability to “hold things together” in space. The desire for its passivity translates into an insistence on representing the matrix in the highest degree of abstraction (such as in mathematical matrix theory), as if there is nothing there at all, separating growth and becoming from its environment, as in a perfect incubator that has no impact on what is inside—except that it supports life.

The metaphoric operations on the matrix have resulted in its twentieth-century definitions: on the one hand, it is an originary place from which all things develop and come into being; on the other hand, it is constituted as the most abstract, mathematically inspired notion of spatial arrangement of numbers, items, ideas, and systems. To support my point, here is an indicative list of the range of meanings of matrix in contemporary circulation, presented by the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary:

“Etymology:

Latin, female animal used for breeding, parent plant, from matr-, mater

Date: 1555

1: something within or from which something else originates, develops, or takes form

2 a: a mold from which a relief surface (as a piece of type) is made b: die c: an engraved or inscribed die or stamp d: an electroformed impression of a phonograph record used for mass-producing duplicates of the original

3 a: the natural material (as soil or rock) in which something (as a fossil or crystal) is embedded b: material in which something is enclosed or embedded (as for protection or study)

4 a: the extracellular substance in which tissue cells (as of connective tissue) are embedded b: the thickened epithelium at the base of a fingernail or toenail from which new nail substance develops

5 a: a rectangular array of mathematical elements (as the coefficients of simultaneous linear equations) that can be combined to form sums and products with similar arrays having an appropriate number of rows and columns b: something resembling a mathematical matrix especially in rectangular arrangement of elements into rows and columns c: an array of circuit elements (as diodes and transistors) for performing a specific function

6: a main clause that contains a subordinate clause.”7

Thus the current meanings of matrix in English highlight productivity (“something within or from which something else originates or takes form”) and receptivity (“material in which something is embedded”). However, these definitions do not include one of the most striking and well-circulated usages of matrix: as a metaphor for virtual space and cyberspace, most conspicuously exemplified and labeled as such in the movie The Matrix. Since the movie has been extensively discussed elsewhere (Žižek 1999; Hochenedel and Mann 2003; Irwin 2002; Diocaretz and Herbrechter 2006), here it will suffice to note that most definitions of matrix issuing from this movie also conveniently miss (or quickly pass over) the relationship to the maternal body while retaining its generative and enveloping properties.8 It is fascinating that the film’s signature image (vertically running green numbers on a black screen, the matrices of zeros and ones) references the mathematical matrix as an array of numbers, while within the plot itself the matrix refers to the machine-generated world in which we are immersed as in a dream while our bodies are imprisoned in a womblike capsule (which echoes and is analyzed via the Platonic “cave” metaphor). In the words of one of the main characters from the movie, Morpheus: “The Matrix is everywhere, it’s all around us, here, even in this room. You can see it out of your window, or on your television. You feel it when you go to work, or go to church or pay your taxes. It is the world that has been pulled over your eyes to blind you from the truth . . . that you like everyone else was born into bondage . . . kept inside a prison that you cannot smell, taste or touch. A prison for your mind. A Matrix” (Wachowski and Wachowski 2001:26),9

We can conclude that the journey of the word matrix is indeed remarkable: from “a female animal used for breeding” and “parent plant” (and “womb”—as per Late Latin usages) to “a main clause that contains a subordinate clause” and “a prison for your mind.” The multiple twists and turns that the matrix as a concept has taken and its widespread popularity today lie in the fact that it has, essentially, enabled a particular and very effective rendering of the concept of space, whether in mathematics, biology, or philosophy.10 I term the matrix effect that which enables the positing of space as hospitable, as in materializing and/or engendering space—in a way, providing “place” to “space.” The matrix seems to be placing space, facilitating its intelligibility. Or, as other usages of the term indicate, matrix seems to possess a form-producing quality; it is a term that indicates how we imagine what forms are and/or come to be (especially in the history of embryology). Taking on the meanings of the mold, imprint bearer, and, later, mathematical number and cyberspace, the matrix today, as it is defined in philosophy, popular culture, and biomedicine, has no relation to the maternal body except through etymology.11 This distancing is noteworthy, as it precludes an ethical relation to the mother; by taking the mother out of consideration in questions of generation and conception, the matrix becomes matricidal.

The concept of chora provides an especially important step in understanding how the meanings of matrix can contribute to a definition of space that includes hospitality. Specifically, an outline of the feminist critique of chora by Luce Irigaray and Emanuela Bianchi demonstrates how the abstract concept of the matrix can be reconnected to the maternal body. This in turn allows one to redefine hospitality beyond a passive notion of tolerance to include the generativity possessed by maternal bodies.

Matrix as Chora: The Mother and Receptacle of All

Wherefore, the mother and receptacle of all created and visible and in any way sensible things, is not to be termed earth, or air, or fire, or water, or any of their compounds, or any of the elements from which these are derived, but is an invisible and formless being which receives all things and...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Journeys of the Matrix: In and Out of the Maternal Body

- 2. Materializing Hospitality

- 3. The Matter of the Matrix in Biomedicine

- 4. Mother-Machine and the Hospitality of Nursing

- 5. Male Pregnancy, Matrix, and Hospitality

- Conclusion: Hosting the Mother

- Notes

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Hospitality of the Matrix by Irina Aristarkhova in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Biotechnology in Medicine. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.