- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

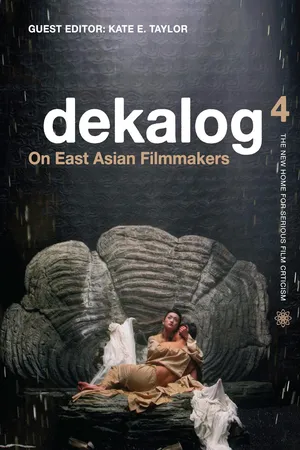

East Asian cinema has become a worldwide phenonemon, and directors such as Park Chan-wook, Wong Kar Wai, and Takashi Miike have become household names. Dekalog 4: On East Asian Filmmakers solicits scholars from Japan, Hong Kong, Switzerland, North America, and the U.K. to offer unique readings of selected East Asian directors and their works. Directors examined include Zhang Yimou, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Rithy Panh, Kinji Fukasaku, and Jia Zhangke, and the volume includes one of the first surveys of Japanese and Chinese female filmmakers, providing singular insight into East Asian film and the filmmakers that have brought it global recognition.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Dekalog 4 by Kate E. Taylor-Jones, Kate Taylor-Jones in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Médias et arts de la scène & Film et vidéo. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Film et vidéoWomen’s Trajectories in Chinese and Japanese Cinemas: A Chronological Overview

S. Louisa Wei

Arguably, the existing writings on Chinese and Japanese cinemas share an obvious deficiency: female directors and their works are often overlooked as they do not readily or neatly fit into existing categories or trends of mainstream and art-house film studies. Whilst Western feminist theories have provoked fundamental re-examinations of ‘her stories’ in literary and visual discourses, substantial studies on female authorship and women’s cinema in Chinese and Japanese contexts have only just begun.

Despite the academic neglect and industrial bias, women are clearly making films. Since 1985 the Tokyo International Women’s Film Festival (TIWFF) has showcased around two hundred films by over thirty female directors from Japan, over twenty from Chinese-language territories and over a hundred from other countries. The organisers of the festival edited an anthology entitled Films of the World Women Directors (2001) and produced two documentaries, Women Make Films: The Tokyo International Women’s Film Festival (2004) and Viva, Women Directors (2007), that respectively introduces 27 female filmmakers from Japan and twelve female directors from Asia and elsewhere. In China, the great achievements of female directors in the early 1980s, and especially in 1985, resulted in the 1986 ‘Forum on Female Directors and Women’s Cinema’, an event attended by ten directors as well as film critics and scholars. The participants discussed such notions as the Chinese tradition of ‘women-themed film’ in comparison to Western concepts such as ‘woman’s film’, ‘feminist film’ and ‘women’s cinema’. In 2009, Women’s Cinema: Dialogues with Chinese and Japanese Female Directors, a book co-authored by Yang Yuanying and myself was published in Chinese. The book includes articles by seven Chinese female directors and 24 long interviews with fourteen female directors from mainland China, three from Hong Kong, one from Taiwan, six from Japan, as well as three TIWFF organiser/curators. In 2011 Chinese Women’s Cinema: Transnational Context edited by Lingzhen Wang was published in English by Columbia University Press and brought together essays on the topic from both sides of the Pacific, and for the first time devoted discussions towards female auteurs and their film works within the transnational cultural discourse.

This essay attempts to present a very brief history from the mid-1920s to 2010 (literally focusing only on women directors and not their male counterparts), and aims to introduce important feature film directors from mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Japan. Since each of these four territories has its own filmic traditions and history, directors are introduced following the chronological order of their directorial debuts and are compared to their contemporaries from other regions. Due to length limitation this essay will mainly include female directors of fiction films and will offer an overview rather that in-depth analysis of the works. Of those directors who emerged since the 1980s, as a general rule only those who directed at least two features will be included. This study serves as one of the first English-language accounts of the historical trajectory of Chinese and Japanese female directors and will hopefully spark further debate and interest across the field.

Pioneer Female Directors: 1920s–1940s

During this period, female directors were very rare in any national cinema although Germaine Dulac (France, 1882–1942), Leni Riefenstahl (Germany, 1902–2003) and Dorothy Arzner (USA, 1897–1979) each received recognition in her own respective national cinemas as prominent female pioneers. Chinese film history maintains that Xie Caizhen (dates unknown) was the first female director from this region; she wrote and directed a silent film entitled An Orphan’s Cry (1925), a family melodrama produced by the Nanxing Film Company. This film caused a huge sensation at the time, partly because it was directed by a woman and partly due to its very complicated plot. Nevertheless despite the film’s success, details of Xie’s career and life (before and after this release), have not yet been unearthed. Like many female directors she has disappeared from the cinematic canon and has been largely forgotten by history.

Another woman who directed films in the 1920s was Wang Hanlun (1903–78) (although no official film history includes her as a director despite her success as an actress). She became a top silent star after her first screen appearance in Orphan Rescues Grandfather (1923), a box-office hit that saved its production company from bankruptcy. Her films made the producers rich but she herself did not get paid; she won a lawsuit against the production company but all she received by way of compensation was a bad cheque. In 1929 she set up the Hanlun Film Company, bought famous scriptwriter Bao Tianxiao’s screenplay for The Revenge of an Actress and invited a renowned director – Bu Wancang – to direct the film. As the director was suffering an emotional breakdown and spent a vast amount of time on the racetrack rather than the set, Wang Hanlun was forced to direct and edit the film herself: ‘I bought the scene breakdown script with 800 yuan, and a projector. I played the film bit by bit at home and cut it bit by bit. After forty days, I finally succeeded’ (Wang H. 1996: 7). She then took the film on tour and screened it in over a dozen cities. She made a fortune and left the film world in 1930. Her story reflects the difficulties women faced in the society at that time as well as the tremendous skills and commitment showed by those early women. It is telling of her personality that according to Wang Hanlun herself, her favorite role was Zhiruo in The Abandoned Woman (1924). After being abandoned by her husband who had a new love, Zhiruo manages to make a living on her own and participates in a woman’s association. When her husband comes to take her back, she rejects him. He then sues her as an escaped wife. She dies while dreaming of a society where women have a say about their own fate.

The only woman directing Chinese-language films in the 1930s and 1940s was American-born Esther Eng (1914–70) who is regarded as the first female director to direct Chinese-language films in both the US and Hong Kong. Betty Cornelius (a.k.a. Betty Bowen), a journalist and keen advocate of women artists, wrote about Esther Eng in the Seattle Times of 9 June 1941: ‘Still in her teens, with no background for such a venture, Esther went to Hollywood, rented a studio on Sunset Boulevard and made her first picture for Chinese markets here and in China.’ Unpublished documents from the Shanghai Film Archive and various 1930s newspapers from Hong Kong also record this venture that resulted in a Sino-American production called Iron Blood Fragrant Soul (a.k.a Heartaches, 1935). In 1936, Esther Eng brought the film, together with its leading actress and her close friend Wai Kim Fong, to Hong Kong. The film was premiered at the Queens Theatre just in time to offer for a patriotic boost for a China where war with Japan was imminent (see Law & Bren 2004: 92).

After China entered into a war with Japan in 1937 she directed National Heroine (1937) featuring a female pilot who fights for her country. The success of the film encouraged Esther Eng to stay in Hong Kong where she made a ‘social education drama’ entitled Ten Thousand Lovers and a romantic tragedy Storm of Envy; both films were released in Hong Kong in 1938. In the same year, she also co-directed Husband and Wife for One Night with Leung Wai-man and Woo Peng. Thanks to her bold creativity and press interest (who wrote not only about her work but also her romance and conflicts with her actresses and other women), her films were highly successful. In 1939 she made an all-actress film entitled Women’s World, which portrayed 36 women in different professions and related the conditions of their existence in society. This film was completed shortly before MGM’s Women (1939), another all-actress film with a crew of 130 women (see Yu 1997: 207). Esther Eng left Hong Kong during the Japanese occupation and made Golden Gate Girl in 1941 in San Francisco. The film received a favorable review in Variety magazine on 28 May 1941 but further Hollywood success did not follow. She arrived in Hong Kong after World War II but failed to make another movie deal there.

Back in California by mid-1947 she made a new film, The Blue Jade (a.k.a. The Fair Lady in the Blue Lagoon), starring Fe Fe Lee, who, like Wai Kim Fong, was also a Cantonese opera actress. Both actresses starred in three films by Esther Eng and both formed a close relationship with her. Apart from The Blue Jade, Fe Fe Lee was also the female lead in two other Ester Eng films: Back Street (a.k.a. Too Late for Springtime, 1948) – about the relationship between a Chinese girl and an Chinese-American GI, and Mad Fire Mad Love (1949) – where she played the mixed-race young woman of a Chinese father and native Hawaiian mother. Mad Fire Mad Love was advertised as the first colour feature made in the Hawaiian Islands and its plot involved the forbidden love affair between a mixed-race woman and a Chinese sailor. Then, with a gap of over a decade, Esther Eng’s last film credit was as the New York location director of Woo Peng’s Murder in New York Chinatown (1961). The film’s producer, Siu Yin Fei (1920–) was a leading film actress and a good friend of hers during her years in New York. During my interview with her in New York on March 24, 2011, she confirmed that Esther Eng directed all exterior scenes while Woo Peng all interior scenes of the thriller.

With ten films to her director’s credit Esther Eng was a pioneer in many senses. She was the first woman to bring a feminist consciousness regarding equal rights for women and the concerns of American-Chinese’s lives into her films. As early as the 1930s she attempted to represent cross-cultural and transnational themes in cinema. She was the first to make Chinese-language films in the US and the first Chinese woman to make sound films in Hollywood (see Law & Bren 2003). And yet her work and the work of nearly all other early female directors are notably missing from the film history canon. Todd MacCarthy, a former critic of Variety, wrote about his complete astonishment when he discovered Esther Eng’s Golden Gate Girl while reading through Variety’s back issues, calling her ‘one filmmaker [who] has utterly eluded the radar of even the most diligent feminist historians and Sinophiles’. It is telling that despite being such an important filmmaker, Variety did not report further news of Esther Eng after the May 1941 review of Golden Gate Girl until her obituary appeared in January 1970 when she died of cancer at the age of 55 (see McCarthy 1995).

Shortly before the Sino-Japanese War, Kyoto-born Sakane Tazuko (1904–75), the former assistant director of Mizoguchi Kenji, debuted as a director with a film entitled New Year Finery (a.k.a. First Image, 1936). She wrote the following in that year: ‘I want to portray the true figure of women seen from the realm of women with a thoroughness combined with my own view of life’ (see Masumoto 2004: 247). During the production of the film, however, Sakane’s crewmembers fiercely rejected her on the grounds of her gender. Even though she finally managed to deliver the completed film it was a critical and box-office failure (see Masumoto 2004: 249) and Sakane was never to direct another feature film. She went to Japanese-occupied Manchuria and became a director of non-fictional films for the Manchuria Film Association (the Japanese colonial production unit in Manchuria). She directed about ten ‘cultural’ films in Manchuria, which were usually one or two reels in length. The only film by her that survives today is A Settler’s Bride (1943). When Sakane returned to Japan after the war, she could not even find a position as an assistant director, and worked as a script coordinator and editor for the rest of her career (see Kumagai 2004).

Chen Bo’er (1910–51), an actress who starred in left-wing stage dramas and films and was most famous for her role in Fate of Graduates (a.k.a. Plunder of Peach and Plum, 1934), was perhaps the only Chinese woman working as a director-producer in the 1940s. An activist during the Sino-Japanese War, Chen entertained Chinese soldiers with stage drama performances and went to the Communist base in Yan’an in 1940. There, she took part in writing plays and film scripts and coordinated the shooting of the famous documentary Defending Yan’an (1947). In 1946, she helped to establish the Northeast Film Studio that was reformed from the former Manchuria Film Association. There she produced seventeen episodes of newsreels on the ‘Democratic Northeast’ in 1947. One of the episodes, entitled ‘Dream of the Emperor’, which she wrote and directed, was the first puppet film of China (literally films made using puppets). Besides producing films, Chen also played an important role in the Central Film Bureau that worked to strengthen the link between her film work and her political ideology.

Post-war Women Directors: 1950s–1962

Seventeen years after Sakane Tazuko directed her first and only feature, Tanaka Kinuyo (1910–77), a top star from the silent film period, made her directorial debut with Love Letter (1953). Tanaka’s film focuses on a male hero who writes love letters for Japanese wives left behind by American soldiers. When commenting on the challenge of taking up the director’s role at the age of 43, she said in an interview: ‘It was really a matter of knowing no fear’; after being treated like a star for decades, ‘it was human skills [that she] needed more than technique’ (in Masumoto 2004: 249). Tanaka’s directorial debut received a vast amount of media attention thanks to both her status as ‘star’ and the film’s subject matter. Post-war Japan had only just been released from the American occupation that had followed the country’s defeat in World War II, and the tale of women abandoned by amorous Americans struck a chord. She continued to work as an actress and directed five more films between 1955 and 1961 including The Moon Has Risen (1955), The Eternal Breasts (1955), The Wandering Princess (1960), Girls of Dark (1961) and Love Under the Crucifix (1962). Criticism related to Tanaka’s work shows that far from just imitating the prominent male directors that she had worked with as an actress, Tanaka constructed her own specific style of film directing. In Japan, her efforts presented a powerful challenge to the idea that women would be incapable of directing films and the previous dismissal of Tanaka as only an actor was remedied. Indeed, in recognition of her skills, Tanaka was the only woman who held membership of the Directors Guild of Japan until her death in 1977 (see Masumoto 2004: 253).

The lack of a consolidated charting of women making films in Japan resulted in Tanaka being mistakenly called the first woman director of Japan. This mistake has resulted in the ignorance of Sakane Tazuko’s work for nearly seven decades. The different fates of Sakane and Tanaka reflect the deep-rooted discrimination against women in Japanese society and the film industry in particular. Without her star power and persistence, even Tanaka would have struggled as a female director working in the male oriented film industry.

The Japanese occupation of Taiwan ended in 1945 with the conclusions of World War II, and native Taiwanese cinema finally began to boom. At the time, films made in Shanghai were brought to Taiwan and achieved great success. China’s Civil War was ended in 1949 after which the Communist government took over mainland China and the Nationalist government moved to Taiwan with a significant amount of capital and a wide group of cultural intellectuals. A large number of Shanghai-based filmmakers moved to Hong Kong and continued to make Mandarin-language films until the 1970s, when Cantonese cinema finally gained an upper hand. Among the 1950s new immigrants to Hong Kong, Malaysian-born actress Chen Juanjuan (1928–67) – ‘China’s Shirley Temple’ – and famous director Ren Pengnian’s daughter Ren Yizhi would eventually become film directors. At this point, Chinese-language cinema split into three separate streams of development in terms of language (Cantonese, Mandarin and/or Taiwanese) and geographical/cultural location (Hong Kong, mainland China and Taiwan).

In Hong Kong, Ren Yizhi (unknown–1979) worked first as an actress and then as a scriptwriter. Between 1955 and 1959 she co-directed eight films, mostly urban melodramas or light comedy, with other more famous male directors. In the 1960s she independently directed three films about love and marriage: An Unfulfilled Wish (1960), Ah, It’s Spring! (1961) and The Four Daughters (1963). She was the first local female director to work in Hong Kong and continued to be the only woman actively directing films from the 1950s to the early 1960s. According to the Hong Kong Film Archive records, her films in this period were all black and white and mostly produced by Great Wall and Phoenix Film Companies. In 1972 she co-directed her last, and only colour, film, Three Seventeen-Year-Olds with Chen Juanjuan (who also co-directed four films with other male directors in the 1960s). Many of these films and the women that made them have been lost to time and more work will need to be done to uncover the works of these forgotten female directors.

In 1957 the female boss of Taipei’s San Chong Ming Theatre, Chen Wenmin, decided to invest in a self-penned romance film entitled Xue Rengui and Liu Jinhua. Even though she had receive...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Series Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction: On East Asian Filmmakers

- An Interview With Naomi Kawase

- Women’s Trajectories in Chinese and Japanese Cinemas: A Chronological Overview

- Fusion Cinema: The Relationship Between Jia Zhangke’s Films Dong and Still Life

- From the Art House to the Mainstream: Artistry and Commercialism in Zhang Yimou’s Filmmaking

- Feng Xiaogang and Ning Hao: Directing China’s New Film Comedies

- Recuperating Displacement: The Search for Alternative Narratives in Tsai Ming-Liang’s The Hole and What Time is it There?

- De-Mystifying a Postwar Myth: Reading Fukasaku’s Jinginaki Tatakai

- Gathering Dust in the Wind: Memory and the ‘Real’ in Rithy Panh’s S21

- Black Hole in the Sky, Total Eclipse Under the Ground: Apichatpong Weerasethakul and the Ontological Turn of Cinema