- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

As critical interest has grown in the unique ways in which art animation explores and depicts subjective experience – particularly in relation to desire, sexuality, social constructions of gender, confessional modes, fantasy, and the animated documentary – this volume offers detailed analysis of both the process and practice of key contemporary filmmakers, while also raising more general issues around the specificities of animation. Combining critical essays with interview material, visual mapping of the creative process, consideration of the neglected issue of how the use of sound differs from that of conventional live-action, and filmmakers' critiques of each others' work, this unique collection aims to both provoke and illuminate via an insightful multi-faceted approach.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Animating the Unconscious by Jayne Pilling in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Mezzi di comunicazione e arti performative & Film e video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Interrogating Masculinity

Revealing Men: The Y Factor

In the hundred years since its birth, live-action film has done a pretty thorough job of showing us what sex, in all its variety, looks like. Maybe it can be the task of animation to tackle the far more interesting question of what it feels like.

In live-action film, sex can be pornographic or erotic, confrontational or titillating. A key element is the ability of film to allow identification with the protagonists. Sexually-charged visual images operate directly on our nervous systems, arousing or repelling the viewer. Animation may not be as good at arousing us or at allowing identification. But it can help us to examine the tangled elements of our experience of sex. Layers of contradictions and ambivalence can be expressed through metaphor, metamorphosis and layering of images. We can be drawn into unexpected somatic identification using movement, and that identification can shift fluidly between protagonists. Sex often obsesses us as human beings, and that obsession can fuel the repetitive work of animation. We can interrogate our own experience and imaginatively inhabit the experiences of others, and we can cross gender boundaries in the process.

There was a time when there seemed to be a clear divide between men’s and women’s animated films. Mens’ films, it seemed, were preoccupied with action, conflict, gags, punch-lines and technical pyrotechnics. Womens’ films were where emotion and soul-baring happened, where the body was given space to speak. Maybe women were pioneers in animating the unconscious, but in the films in the Desire and Sexuality: Animating the Unconscious DVD collection (2007) we see that men are using this medium to examine their darker places, and to explore and empathise with the female experience.

In The Secret Joy of Falling Angels (1991), Simon Pummell examines the complexity of a sexual encounter between a woman and a bird-like creature of indeterminate gender.

Secret Joy… is a film made at a time when our perception of sex was inflected and infected by the fear of AIDS. Sex had become a barbed thing, and a generation was newly aware of the links between eroticism and death. We can maybe trace the shadow of AIDS in the art of this time as, with the benefit of longer hindsight, we recognise the shadow of syphilis in the art of the fin-de-siècle, in the unwholesome beauty of symbolism and art nouveau.

The point of departure for Secret Joy… was Renaissance paintings of the Annunciation. Pummell was interested in the nuanced layering of gesture – resistance, fear, awe and acceptance. The figure of Mary holds her hands up, or crosses them across her breast. She gestures to say ‘Me?’ and ‘Not me!’ and to question and repudiate. But her head and face incline towards the angel, in a gesture of submission. Pummell recognised these contradictory gestures as expressive of the complexity of human eroticism. The film imagines an erotic encounter between a woman and a bird/human creature that looks less like an angel than a monstrous chimera. The woman is fleshy and sensual, morphing between a sensual realism and a grotesque glamour.

The film is constructed with several contrasting techniques; graphite drawing, coloured pastels, stop-motion with articulated bird skeletons, and acrylic paintings. The paint suggests feathers, interior body spaces, abstract images mirrored to create a vaginal Rorschach pulsing. Still paintings are moved under the camera. Pummell cleverly integrates the disparate elements by echoing movement across techniques, and by making the drawing appear initially as a shadow occupying the same universe as the birdcage. Backlighting is used throughout, unifying the look of the piece. Sound enhances an unsettling and sensual world of textures.

Although this is a film by a man, we feel a convincing female subjectivity at its core. This is in part created by the intimacy and emotion of Annabel Pangborn’s voice. The constant shifting of the woman’s body between desirable and grotesque feels like an expression of a mobile internal state rather than the product of misogyny. This is both a cool and a passionate film.

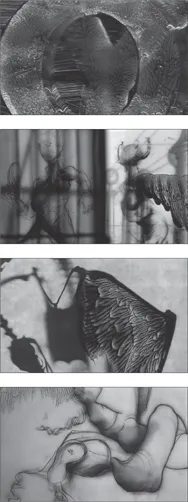

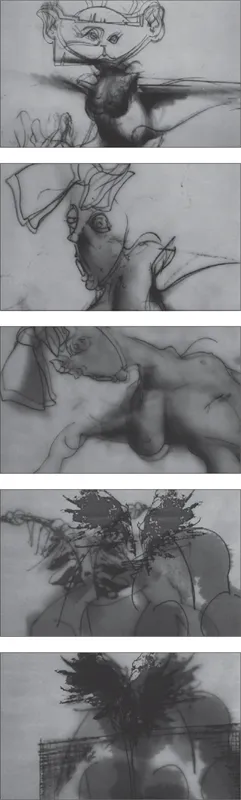

Images from The Secret Joy of Falling Angels (1991) © Channel Four Television

Early in the film we are invited – first via the letter O, then via a mirror – into the woman’s vagina, as experienced subjectively, into an inchoate pulsing world. The music suggests melancholy, even the presence of death. The sexual act in the film often seems to be happening between two versions of the same woman. The vagina is maybe the most important and most insistent protagonist in the film.

The only time we see male genitalia is in the distortions of the woman’s body, and implied in the aching voids of mouth and vagina. It is only the clear act of impregnation that tells us that this is definitely a coupling of two creatures, male and female. The angel often has breasts. Maybe the idea of the angel suggests a freeing of the sexual spirit from the confines of the gendered body. It is the skeleton bird that most clearly represents the penis; it’s blind, frantic thrashing with its creaking sound effects contrasting with the deeper pulsing rhythms of the female images. The bird, according to Pummell, comes from the dove often seen in Annunciation paintings as the embodiment of the holy spirit. But birds to Pummell are also objects of a certain revulsion, seeming to him to be mindless bio-mechanisms.

The insistence and urgency of sexual desire are built up by the abstract rhythms of the animated painting, the beating of the wings, the growing intensity of the pace and cutting. Bird skeletons couple in a frantic spasm, an abjectly physical counterpoint to the psychic transcendence of orgasm.

But it is the drawings that allow us to experience the particularity of the erotic experience. The drawings recall several things at once: anatomical drawings; Disney line-tests; and the exquisite unwholesomeness of Hans Bellmer’s drawings. But animation can go further than still drawing when it comes to Bellmer’s quest to disrupt the syntax of the body. Breasts morph into testicles, into the wattles on a grotesque face, man into woman, realism to grotesque caricature, the boundary line of the body is stretched into abstraction and geometry. The drawings suggest the loosening of boundaries that make eroticism dangerous. They are repeated backwards and forwards, creating a repetitive, swinging action which is in contrast to the frenetic rhythms of the skeletons and the pulsing paint. Ripple-glass effects give us a different sort of pulsing, with an underwater feeling. These rhythms recall breathing, heartbeat, the involuntary spasms and contractions of digestion and sex.

Images from The Secret Joy of Falling Angels

The drawings mix gestural line, indicating the dynamics of movement, shadow, creating weight and a sense of flesh on the bone and a controlled but mutable boundary line that defines and describes. We also see the traces of movement in the layers of backlit drawings. Although loose and mutable, the drawing is sufficiently anatomically convincing to allow us to experience the sensuality and the burden of flesh, with its weight and pendulousness. The painted acrylic sequences gives the impression of feathers, of fingerprints, of the inner space of the body. They are tactile in a double-edged way, attracting and repelling with a sort of unwholesome stickiness. At times they imply a moist meatiness.

The portrayal of orgasm in this film is something that feels authentic. The drawing allows the loosening of boundaries, the shifting of identification. As in the best sex, we are unsure where one body ends and the other begins. Body parts morph and change gender. Emotionally we take a journey through fear and resistance, through a frantic montage of skeleton shots, into a strangely calm centre, where time slows and there is an intense sweetness. It is no longer clear who the wings belong to. This is sex act as narrative, where the dénouement is the beginning of a new life. The bird-foetus is glimpsed in the woman’s belly, while the resolution of the voice tells us that everything is going to be all right.

Pummell’s evocation of meaty subjectivity, the mortality of the body, its weight and the way it binds us to the earth and offers moments of transcendence is something which we may associate more with womens’ filmmaking, with animators such as Vera Neubauer, Joanna Quinn and Michèle Cournoyer. And Pummell is one of few men whose work approaches the self-exposure of women animators like Alison De Vere, Alys Hawkins and Emily Hubley.

One other is Andreas Hykade, who subjects male sexuality to a merciless gaze. In his world, masculinity is a problematic burden and its integration into a fully emotionally functioning selfhood is a moral challenge. Hykade has been accused of misogyny, but in fact he tends to idealise women – the dandelion girl of We Lived in Grass (1995) and the water-haired love-object of Ring of Fire (2000) are personifications of the female principle as life-giving and of central importance. The mother in We Lived in Grass can be seen as an abject baby-machine but in fact she is a strong and complex character, though we are given a strong sense of the depredations of being a wife and mother on her body.

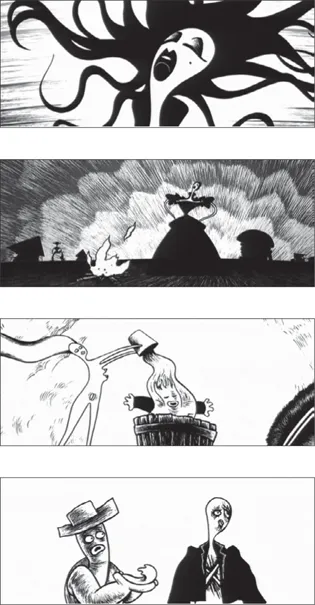

Image from Ring of Fire (2000) © Andreas Hydake

And the gipsy prostitute in Ring of Fire is a majestic figure, allowing access to her mysteries only on her own terms. The more abject images of sex in the film seem clearly to be mere projections of male desire. Through the cowboys’ eyes, we see the world of sexual relations as an excessive carnival of disembodied body parts offered for commerce. This commerce depends on a performance of masculinity, from which the inept cowboy runs, humiliated, only to stray into the heroine’s territory, where he is bathed in the generous waters of the female principle. The beautiful heroine is suborned and raped by the competently evil cowboy, while the inept cowboy enters the gipsy’s tent, where he is awe-struck at the revelation of her endless sexual mysteries.

Images from Ring of Fire

Hykade’s drawing is permitted by its intense stylisation to show sex graphically and in a perverse and dizzying variety. But the most intense expression of eroticism in his film comes in the form of a metaphor, that of the pouring of water. The end of the film, where the softer cowboy washes the damaged heroine, is at once erotic and moving. Here we see the equal erotic exchange between a man and a woman as healing and life-giving.

Igor Kovalyov’s films deal with eroticism as part of the complex web of relationships. In Milch (2005) the love object is a personification of healthy carnality, desired both by the father and the son. But the film is equally concerned with looking at power relations within the family, and the learning of masculinity by the son. We see sex through the boy’s eyes as a rich and disruptive force. His pent-up energy in the oppressive silence and tension of his home is expressed in the repetitive banging of his wooden car against the wall, his kicking a ball which we hear breaking a window, and by his sexual obsession with the girl. The rich visual textures of the film, along with its evocative sound, allow us to experience the film with all our senses. In the alley where the father and the girl have a highly charged encounter we can smell the caged circus lion. Kovalyov’s work is full of musical rhythms and tiny gestures which illuminate human relationships.

In How Wings are Attached to the Backs of Angels (1996), the woman’s sensuality is contrasted with the controlling reductionism of the man’s desires. This is beautifully expressed through the graphic style – the male world is depicted in a mannered Victorian style, obsessively mechanistic. In this world, observation and science are all about control. Nature is there to be tortured and manipulated with tiny surrogate hands, putting touch and feeling at a distance. The female, depicted in live-action, is grainy, real, capable of pleasure and emotion. The fear she inspires in the man is that of his own mortality. She defies his control and makes him experience himself as flesh, vulnerable to being decapitated/c...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction

- Women: From Outside In and Inside Out

- Interrogating Masculinity

- Modes of Reality

- Index