- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Critical Cinema: Beyond the Theory of Practice purges the obstructive line between the making of and the theorising on film, uniting theory and practice in order to move beyond the commercial confines of Hollywood. Opening with an introduction by Bill Nichols, one of the world's leading writers on nonfiction film, this volume features contributions by such prominent authors as Noel Burch, Laura Mulvey, Peter Wollen, Brian Winston and Patrick Fuery. Seminal filmmakers such as Peter Greenaway and Mike Figgis also contribute to the debate, making this book a critical text for students, academics, and independent filmmakers as well as for any reader interested in new perspectives on culture and film.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Critical Cinema by Clive Myer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Film & VideoPART ONE

REFRAMING

CHAPTER 1

THEORETICAL PRACTICE: DIEGESIS IS NOT A CODE OF CINEMA

Clive Myer

In considering the space between imaginary action and social action, I intend to push the boundaries of the filmic notion of diegesis as ‘the viewer’s mental referent’ beyond that which Noel Burch in the early 1970s in his address to film students at the Royal College of Art defined as the mental referent that connects the viewer to that which is viewed. At that particular historical moment the term could be said to have contained a certain dialectic which connected theory to practice, an opening to an understanding of the production of knowledge that engendered possibilities for a counter cinema, now lost in the institutional framework of education and, some would say, devoured by the television zapper and music clip.1 I take as given the existence of a certain contemporary conjuncture: a mental and corporeal ever-changing and sophisticated relationship between screen action and social action (and beg the question of cinematic intention and indeed intervention) and a social and cultural progression whereby postmodernism and indeed the social fabric of society are undergoing quite radical forms of transition. There would seem to be an urgent need to re-assess a number of definitions that have become part of media folklore and my intention here is to re-evaluate the notion of the diegetic space of cinema as a ‘place between’ and a ‘place beyond’ the binary concept of a representational world and a social world. In the struggle for the teaching of a cinema of knowledge (involving the pleasure of knowledge, the pleasure of critical thinking and the pleasure of critical practice), I aim to recuperate the term diegesis from its now institutionally bound usage as particularly seen within the frameworks of Cultural Studies and Film Studies as well as a now fairly common mode of description within film schools and independent film practice in general.

I

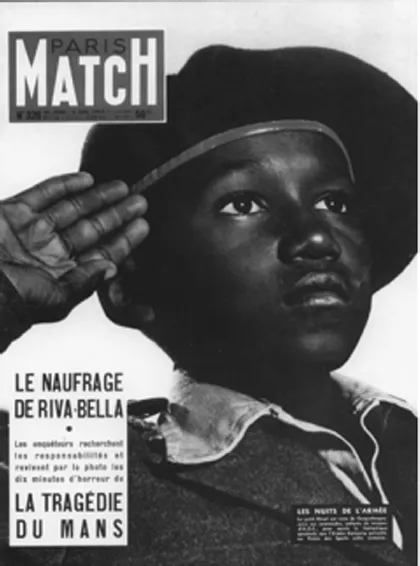

Let us look at the term diegesis. Etymologically, the word suffers from differing French and English linguistic translations from the Greek διήγησις (De Grève 2007). It was first used by Plato in The Republic to describe direct narration, the telling of a theatrical story or poem through the presence of the narrator, so the term did not refer to the narrative content per se but the ‘telling’ of the narrative. It was then revised by Plato’s pupil Aristotle as a ‘mode of mimesis’ (Taylor 2007), the ‘enactment’ of the narrative. Mimesis translates from the Greek as ‘imitation’ bringing it closer to the problematic description of the reflection of reality as corroborated by Paul Ricoeur (1984: 180) who reminds us that Plato did not separate mimesis from diegesis but recounted two forms of diegesis, the one ‘plain’ diegesis which is direct narration (the voice of the narrator) and the other ‘by imitation’ whereby the narrator imitates the voice of the character. Aristotle, in separating the two, recognised mimesis as the term most descriptive of the development of narrative form. Consequently, decontextualised adaptations of the term diegesis for cinematic usage have slid between the French distinctions of the Platonic form of the ‘pure’ (Biancorosso 2001) or ‘plain’ (Ricoeur 1984: 180) delivery of a narrative by the narrator in contrast to the mimetic function of the narrative demonstrated by illusory third parties, by now in the form of actors rather than the narrating poet. Ricoeur warns that we have to be constantly on guard against the superimposition of the two. In the context of cinema, the term was first used by Etienne and Anne Souriau and a group of French intellectuals in the 1950s as part of a series of descriptive technical terms (such as profilmic and afilmic)2 but spelt diégèse differing from Plato’s ‘pure’ narrative (or ‘narration’ in the sense of the absence of ‘impure’ dialogue) spelt diégésis. The Souriaus’ intervention defining diegesis as the world within the narrative resulted in the use of the term as narrative content. However, it was Gérard Gennette in 1972 who, in returning to the Souriau definition, reinforced the term as a potentially radical post-Aristotelian space, contextually innovated by the conscious action of the viewer in recognising the diégèse as ‘the universe where the histoire (story/history)3 takes place’ (Genette 1988: 17–18). In keeping with the French double meaning of histoire this universe may be considered as not just the story or narrative bracketing but as a social structure that also contains the history of its meaning and the context of its future regeneration within the diégèse. The diegetic now becomes an ideological black hole that sucks into the nature of its existence not only the formal articulations that bracket the signification of the narrative but also the history that gave birth to the ideas and articulations and the social, ideological and economic contexts that engendered the history in the first place. Burch’s recent postformal perspective,4 might read Genette’s holistic approach to the diegetic as dystopic, commenting, as Burch does, on what he now considers to be an irreversible victory of the dominant system of representation and ideology contaminating ‘all there is I see’ (see chapter 14). This includes profilmic, filmic and postfilmic5 referents wherein is contained not just the history but also the desires (imaginary future) of the audience. Earlier Formalist and Structuralist notions from Burch (1973) and Christian Metz (1973) however, would have had more in common with Souriau’s separation of profilmic reality and filmic reality in his reference to ‘all that I see on the screen’ (Lowry 1985: 73–97; emphasis added), imbuing the diegetic with a representational framework which depicts the filmic reality operating through the relatively autonomous self-contained reality that each individual film brings with it – ‘everything which concerns the film to the extent that it represents something’ (ibid.; emphasis added). This definition, tending to separate representation from reality, contains the kernel of certain structuralist and deconstructive approaches to cinema from the 1970s which emphasise the signifier over the signified whereby the interpretation of representation privileges the form over meaning and distances the subject from the means of expression. Burch attributes his own use of the term to Metz (see chapter 14) but Metz re-attributes it back around to Etienne Souriau (Metz 1982: 145). Metz argued that modern-day use had distorted its Greek origins particularly with the two different spellings in French, and I argue now that the English translation as ‘narrative or plot’ (Concise Oxford Dictionary 1999) disappointingly avoids the potential of the philosophical aspect of the French meaning altogether (which I would call ‘contextual imaginary’) which, although still operating on the plane of the illusory, at the level of ideas maintains a perspective for a polemical imaginary. In contradistinction to this complex interpretation of the diegesis, the English usage conflates the Greek origin with a literal French rendition didactically neutralising the reading of the word from its representational, worldly and Other dialectical possibilities. The English definition depoliticises the essence of the French translation rendering it harmless to the dominant cinematic system compared to the Burchian more radical expectations of a diegesis invoking active, dynamic and potentially disruptive relationships between the viewer and the viewed. Since that time it has been assimilated (incorrectly, I believe) within film theory and practice at best as ‘on-screen fictional reality’ (Hayward 2006: 101). But what does that mean and what are its implications for practice? Sound theorist and practitioner Michel Chion has described the use of onscreen and offscreen music as diegetic and nondiegetic – descriptions that have since been used regularly in film teaching and reflected in student essays and journals. Chion brings the concept of the nondiegetic to the fore, suggesting that, for instance, background music is nondiegetic and synch dialogue is diegetic (Chion 1994: 67). Although he quite amply describes sounds that ‘dispose themselves in relation to the frame and its content’ (68) as onscreen and those that ‘wander at the surface and on the edges’ (ibid.) as offscreen he still distinguishes others that ‘position themselves clearly outside the diegesis’ (ibid.) such as voice-overs that belong on the balcony or orchestral music that belongs in the pit. But does this empirical use of the term serve to simplify and transform a motivating philosophical concept to one that becomes a predetermined code of cinema? From my own perspective, which I discuss later as operating within the postdiegetic social world, the notion of the ‘nondiegetic’ is a historically relevant but now redundant term useful only to the period of the poststructuralist discourse and a red herring for those working with the non-binary poetics of theory for practice. Chion admits that his definitions and diagrammatic explanations of the concepts of onscreen, offscreen and nondiegetic space, which derived from his earlier work La Voix au Cinéma (1982), have become problematic and have been ‘denounced as obsolete and reductive’ (Chion 1994:74). Notions of the diegetic and nondiegetic manifest as codes of cinema may be the consequence of the confusion over the term diegesis, after all Metz and Burch wrote avidly on the codes of cinema. As an example of diegesis Burch alighted upon the ten-gallon hat as a sign of the ‘cowboy film’6 which legitimatised the viewer to enter that space from their own, socially implanted, imaginary set of relations with the world of the film. Burch was an avowed Althusserian. Louis Althusser promoted a philosophical and politically analytical approach to the study of culture, emanating from a late Marxist examination of the State Apparatus and its implications for ideology. At this time, the concept of the sign, imbricated with semiotic activity and embraced by optimism for cultural counter insurgency, was a theory steeped in potential for political and cultural empowerment in the wake of 1968 power relations in France and elsewhere in mainland Europe. In the UK, through the pages of Screen in particular, the Ideological State Apparatus became a blackboard for the development of film theories and practices that responded to and attempted to displace dominant ideology. The world of mental referents heralded a battlefield for a war on ideology where Roland Barthes’ analysis of the front cover of an edition of Paris Match, the image of the young black soldier saluting the French flag, was, to some, as much a romantic anti-narratological call to arms as it was contradictory heroism within the narrative of the photograph itself (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 The world of mental referents heralded a battlefield for a war on ideology. Cover of Paris Match 25 June –2 July 1955

The telling of the story of the photograph became as iconic as the notion of black youth/French flag. Postmodernism absorbed this image until it became the equivalent of a new French flag, bringing to mind John Berger’s well known reference to the Mona Lisa as an example of acquiescent entrapment within the perspective of Walter Benjamin’s notion of mechanical reproduction as demonstrated in Ways of Seeing (1972). The expressive awareness and observations of Modernism were shifting from creative acts of discovery to ironic reactions to consumerism. The apparent innocence of the signification of social mass consumption and built-in obsolescence in a Warhol silkscreen contained its own sense of contradiction and the potential for the postmodern irony of the next two to three decades. Structuralism, in representing the critical voice of late Modernism, had laid the path for the elision of Capitalism with cultural radicalism. After the failure of the left in France in 1968 and the failure yet again in the UK in 1984 no longer could aesthetic exploration be seen as a struggle in consciousness but rather as ‘the expression of a new social conservatism’, as Fredric Jameson remarks in the introduction to Jean-François Lyotard’s The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge, (1984: xvii). Terry Eagleton indicates in After Theory (2003) that the shift from the philosophy of philosophy (for example, the study of the floating signifier) to the application of the result (for example, the study of Hindu nationalism, or the study of the shopping mall) could be welcomed on the one hand but was ‘not entirely positive’ on the other. It had become ‘typical of a society which believed only in what it could touch, taste and sell’ (Eagleton 2003: 53).

The notion of the diegetic had by this time, observed through my own teaching practice, become part of the vocabulary of the relatively new Humanities disciplines of Film Studies, Media Studies and Cultural Studies and by default part and parcel of a consuming and growing industry of education. It had lost its meditative force in favour of the descriptive and had been drawn into pragmatic academia. I say this by no means as an attack on the good intentions of the academics and committed university lecturers but about its very exploitation by the institutions in which they are contained. There, the fervour of a supply and demand approach to education saw the multiple expansions of student numbers and off-shoot related courses, leading to often weakened programmes and a most definitely alienated film and media industry. Within this revisionist historicism, discussed by David Bordwell as a result of the professionalisation of film research (Bordwell 1997: 139–40), the diegesis became another term for the narrative, not simply as storytelling but as a framework for the containment of narrative. D.N. Rodowick describes diegesis as the ‘denoted elements of story’ (1994: 113) and defers to Metz’s suggestion that the aim of narrative in film is ‘to efface film’s material conditions as a discourse in order to better present itself as story; in sum, the diegesis or fictional world is given as the expression of a signified without a signifier’ (Rodowick 1994: 134).

As an extension and an oversimplification of this conceptual proposition, not only could institutional academia now speak of the world contained within the film’s diegesis but also of the world outside the diegesis. The often misused notions in film studies of diegesis as ‘the main narrative’ (Tredell 2002: 158) or that which stands outside the story as ‘extra-diegetic’ (159), or that which is present but does not exist within the narrative as ‘nondiegetic’,7 belies the philosophical complexity of diegesis and its special place within the triangulated modernity of form, content and context. It generates a reductive description of onscreen or offscreen space as the place of the diegesis as it relates to the Platonic truth of the narrative. Offscreen space is referred to often in Burch’s writings. This is not so-called nondiegetic space, but is exactly what it says on the label – the space of the world not framed. It is not the nondiegetic space that Chion separates from onscreen and offscreen, but it most certainly plays a role in the diegetic nature of the viewing experience–after all, the diegesis as I will now define it, is present in the total experience of the viewing subject, whether in the realm of what we see and think or in its opposite state of absence in the world of the unobtainable Other (born from language and operating on the symbolic level of the unconscious).8 You see, the diegetic is not a ‘thing’ it is a process, it is not sustainable as the diegesis or the absence of the diegesis in its own right. If the imaginary presence of the diegetic is experienced when engaged in the act of viewing a film and it is the mental referent embedded in myth and locked between the subject-being in (permanent) transition and the object of desire (which is both the filmed image and the image-in-the-world) then its self-perpetuating culture expa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Notes on Contributors

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Part 1: Reframing

- Part 2: Conversations

- Index