![]()

1

STORIES OF CONTROL

The General Electric Company was science fiction.

—KURT VONNEGUT

THROUGHOUT history and across cultures, civilizations have told stories about gods and heroes who have attempted to control that which may be largely uncontrollable, including phenomena both above and below the horizon. There are many sources for such stories. Myth, religion, and traditional practices form the foundations of culture and are often invoked when people seek group solidarity—for example, when the expected rains fail to arrive or a violent storm rages. Stories drawn from Greek mythology, the Western canon, Native American rainmaking, and recent fiction are presented here, followed by examples of geo-science fiction before about 1960—drawn from the pages of pulp fiction, the stage and silver screen, and the boob tube—that serve to illuminate popular culture. But much more than edification is at stake. Storytelling skirts the borderlands between fact and fantasy and acknowledges their reciprocal relationship. Here the comic and tragicomic genres provide fresh insights into the speculative practices of the meteorological Don Quixotes and Rube Goldbergs of the past. Such storytelling clearly trumps the heroic and the tragic genres so typical in the literature of science studies. It is an excursion that historians of science, technology, and environment have only recently begun to take.

dp n="33" folio="16" ?

Phaethon’s Blunder

In uncovering the deeper cultural roots of weather and climate engineering, it is instructive to consider the wisdom invested in mythological stories, since whether we realize it or not, much of Western civilization rests on these foundations. In Greek mythology, the youth Phaethon lost control of the Sun chariot, and his recklessness caused extensive damage to the Earth before Zeus shot him out of the sky. The story began when Phaethon, mocked by a schoolmate for claiming to be the son of Helios, asked his mother, Clymene, for proof of his heavenly birth. She sent him east toward the sunrise to the awe-inspiring palace of the Sun god in India. Helios received the youth warmly and granted him a wish. Phaethon immediately asked his father to be permitted for one day to drive the chariot of the Sun, causing Helios to repent of his promise, since the path of the zodiac was steep and treacherous and the horses were difficult, if not impossible, to control. Helios replied prophetically, “Beware, my son, lest I be the donor of a fatal gift; recall your request while yet you may.... It is not honor, but destruction you seek.... I beg you to choose more wisely.”1 But the youth held to his demand, and Helios honored his promise. At the break of dawn, the horses were harnessed to the resplendent Sun chariot, and Helios, with a foreboding sigh, urged his son to spare the whip, hold tight the reins, and “keep within the limit of the middle zone,” neither too far south or north, nor too high or low: “The middle course is safest and best” (63).

Now Phaethon spared the whip; that was not the problem. A bigger problem was that the youth was a lightweight (literally) and the horses sensed this, “and as a ship without ballast is tossed hither and thither on the sea, so the chariot, without its accustomed weight, was dashed about as if empty” (64). Also Phaethon was a completely inexperienced driver without a clue as to the proper route to take: “He is alarmed, and knows not how to guide them; nor, if he knew, has he the power” (64). The chariot veered out of the zodiac, with hapless Phaethon looking down on the vast expanse of the Earth, growing pale and shaking with terror. He repented of his request, but it was too late. The chariot was borne along “like a vessel that flies before a tempest,” and Phaethon, losing control completely, dropped the reins. So much for the middle course:

The horses, when they felt them loose on their backs, dashed headlong, and unrestrained went off into unknown regions of the sky, in among the stars, hurling the chariot over pathless places, now up in the high heaven, now down almost to earth.... The clouds begin to smoke, and the mountain tops take fire; the fields are parched with heat, the plants wither, the trees with their leafy branches burn, the harvest is ablaze! But these are small things. Great cities perished, with their walls and towers; whole nations with their people were consumed to ashes! The forestclad mountains burned.... Then Phaeton beheld the world on fire, and felt the heat intolerable. The air he breathed was like the air of a furnace and full of burning ashes, and the smoke was of a pitchy darkness. (65–66)

1.1 Phaethon, from the series The Four Disgracers (1588) by Hendrick Goltzius (Netherlandish, 1558–1617). Icarus, Ixion, and Tantalus are also called “disgracers” for their overweening ambition.

With the Earth on fire, the oceans at risk, and the poles smoking, Atlas did more than shrug—he fainted. The Earth, overcome with heat and thirst, implored Zeus to intervene, “lest sea, Earth, and heaven perish, [and] we fall into ancient Chaos. Save what yet remains to us from the devouring flame. O, take thought for our deliverance in this awful moment” (67). Zeus responded by shooting the devious charioteer out of the sky with a fatal lightning bolt as Helios looked on in shock and dismay (figure 1.1). A utilitarian ethic applies in the myth. After much of the Earth was incinerated, Phaethon was killed by a higher authority to avoid further damage. And rightly so.

The story of Phaethon was invoked in 2007 by the noted meteorologist Kerry Emanuel to frame a short discussion of contemporary climate change science and politics. Emanuel, widely known and respected for his hurricane studies, called attention to a growing scientific consensus on climate change prominently and authoritatively spearheaded by today’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports, yet he admitted pointedly that “we are ... conscious of our own collective ignorance of how the climate system works.”2 Abruptly returning to myth, Emanuel ended his essay, “Like it or not, we have been handed Phaeton’s reins, and we will have to learn how to control climate if we are to avoid his fate” (69; emphasis added). Emanuel thus advocated repeating Phaethon’s blunder. Think underage driver of gasoline tanker, taken with father’s permission, veers out of control in reckless, high-speed chase before being subdued by the authorities. Or more globally, geoengineering project given the green light last year results in the collapse of the Indian monsoon, leaving millions starving.

What about Emanuel’s final thought—that we “will have to learn how to control climate”? That is the subject of the final chapter of this book. Cambridge scientist Ross Hoffman has proposed a speculative “star wars” system to redirect hurricanes by beaming lasers at them from satellites—assuming one knew where the storm was originally headed and that there would be no liabilities along its new path. Is this an example of Phaethon’s reins? Since the Sun god Helios was directly involved, what about other means of “solar radiation management,” such as Nobel laureate Paul Crutzen’s suggestion (made in 2006, but actually a much older idea) to cool the Earth by injecting sulfates or other reflective aerosols into the tropical stratosphere? There are many, many more such dangerous and expensive proposals of environmental control that invoke the inexperience and possible tragedy of the myth of Phaethon.

Remember, Helios made a fundamentally flawed decision to give his son the reins, and that decision had catastrophic consequences. He did, however, give Phaethon a piece of good advice about steering the Sun chariot through the middle course of the zodiacal signs. For humanity, the best we can do between this world and the next is to admit our “own collective ignorance,” remain humble, and avoid angering both the Sun god and his boss. Will this involve following the “middle course” of collective energy efficiency, environmental stewardship, and ethical choices? Certainly to do nothing is out of the question. But could we try to do too much? Will someone or some group trying to “fix” the climate repeat Phaethon’s blunder? Greek mythology is replete with such stories, characters, and moral lessons.

dp n="36" folio="19" ? Paradise Lost and the Inferno

Biblical themes permeate the Western canon, and some of them speak either directly or indirectly to the human role in weather and climate control. In Paradise Lost (1667), John Milton alludes to a divinely instituted shift in the Earth’s axis (and thus its climate) as a consequence of the original ancestors’ lapse from grace. According to Milton, while Eden was the ultimate temperate clime, watered with gentle mists, God, in anger and for punishment, rearranged the Earth and its surroundings to generate excessive heat, cold, and storms: “the Creator, calling forth by name His mightie Angels, gave them several charge.”3 The Sun was to move and shine so as to affect the Earth “with cold and heat scarce tolerable” (10.653–654); the planets were to align in sextile, square, opposition, and trine “thir influence malignant ... to showre” (10.662); the winds were to blow from the four corners to “confound Sea, Aire, and Shoar” (10.665–666); and the thunder was to roll “with terror through the dark Aereal Hall” (10.667). The biggest change, however, resulted from tipping the axis of the Earth: “Some say he bid his Angels turne ascanse the Poles of Earth twice ten degrees and more from the Sun’s Axle; they with labor push’d oblique the Centric Globe ... to bring in change of Seasons to each Clime; else had the Spring perpetual smil’d on Earth with vernant Flours, equal in Days and Nights” (10.668–671, 677–680).

This led to massive changes in weather and climate on sea and land: “sidereal blast, Vapour, and Mist, and Exhalation hot, Corrupt and Pestilent” (10.693–695). Northern winds (Boreas, Kaikias, and Skeiron) burst “their brazen Dungeon, armd with ice and snow and haile, and stormie gust and flaw” (10.697–698), and other winds (Notus, Eurus, and the Tempest-Winds) in their season rent the woods, destroyed crops, churned the seas, and rushed forth noisily with black thunderous clouds, serving the bidding of the storm god Aeolus. But the angels had one last task: evicting “our lingring Parents” (12.638) from Eden. In this, too, Milton evokes climatic change when the blazing sword of God, “fierce as a Comet; which with torrid heat, and vapour as the Libyan Air adust, began to parch that temperate Clime” (12.634–636). Looking back at Paradise, “som natural tears they drop’d, but wip’d them soon; the World was all before them, where to choose thir place of rest, and Providence thir guide: They, hand in hand, with wandring steps and slow, through Eden took their solitarie way” (12.645–649). So you see, the wages of sin are ... climate change.

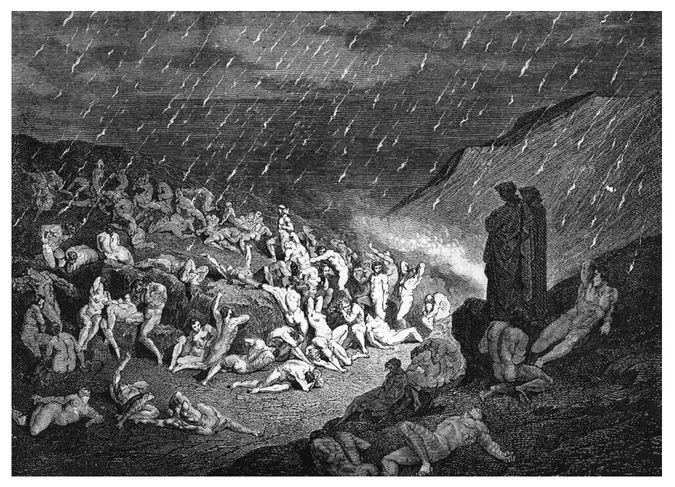

When Dante Alighieri visited hell with Virgil in the spring of 1300, he witnessed the consequences of sin. They had left a world with “air serene” and entered “into a climate ever vex’d with storms ... where no light shines.”4 Before them, confined to the third circle, were the gluttons experiencing unique meteorological torments of eternal cold and heavy rain, hail, and snow (6.6–11), while in the seventh circle were those who had done violence to God, naked souls weeping miserably, supine, sitting, wandering, muttering, under a steady rain of “dilated flakes of fire” (14.18–27) (figure 1.2). Today we might add a new caption to Gustave Doré’s illustration: Sulfurous rains fall on a wretched humanity following artificial volcano experiment gone awry; two geoengineers look on.

1.2 Inferno: “The violent, tortured in the Rain of Fire,” in Dante’s version of hell. (ILLUSTRATION BY GUSTAVE DORÉ, FOR INFERNO 14.37–39, 1861)

The heavens and “heaven” have never been strictly demarcated; in fact, they have been closely intertwined, especially when it comes to something at once as nebulous and portentous as atmospheric phenomena. Synergistic rather than conflicting interactions between the numinous and the immanent appear to be more the norm than the exception throughout history. Humans attempting to intervene in the “realm of the gods,” whether through ceremonies or technologies, inevitably find themselves engaged in a complex dance with both novel and traditional steps, where stumbling and falling from grace, or at least stepping on toes, is more likely than perfect execution.

dp n="38" folio="21" ?

The Mandan Rainmakers

The nineteenth-century American painter George Catlin juxtaposed traditional rainmaking and Western technology in his account of the manners and customs of North American Indians. When the Mandan, who lived along the Upper Missouri River, were facing a prolonged dry spell that threatened to destroy their corn crop, the medicine men assembled in the council house, with all their mystery apparatus about them, “with an abundance of wild sage, and other aromatic herbs, with a fire prepared to burn them, that their savory odors might be sent forth to the Great Spirit.”

5 On the roof of the council house were a dozen young men who took turns trying to make it rain. Each youth spent a day on the roof while the medicine doctors burned incense below and importuned the Great Spirit with songs and prayers:

Wah-kee (the shield) was the first who ascended the wigwam at sunrise; and he stood all day, and looked foolish, as he was counting over and over his string of mystery-beads—the whole village were assembled around him, and praying for his success. Not a cloud appeared—the day was calm and hot; and at the setting of the sun, he descended from the lodge and went home—“his medicine was not good,” nor can he ever be a medicine-man. (1:153)

On successive days, Om-pah (the elk) and War-rah-pa (the beaver) also failed to bring rain and were disgraced.

On the fourth morning, Wak-a-dah-ha-hee (hair of the white buffalo) took the stage, clad in his finest garb and with a shield decorated with red lightning bolts to attract the clouds and a sinewy bow with a single arrow to pierce them. Claiming greater magic than his predecessors, he addressed the assembled tribe and commanded the sky and the spirits of darkness and light to send rain. The medicine men in the lodge at his feet continued their chants.

Around noon, the steamboat Yellow Stone, on its first trip up the river, neared the village and fired a twenty-gun salute, which echoed throughout the valley. The Mandans, at first supposing it to be thunder, although no cloud was seen in the sky, applauded Wak-a-dah-ha-hee, who took credit for the success. Women swooned at his feet, his friends rejoiced, and his enemies scowled as the youth prepared to reap the substantial rewards due a successful rainmaker. However, the focus quickly shifted to the “thunder-boat” as it neared the village, and the hopeful rainmaker was no longer the center of attention. Later in the day, as the excitement of the boat’s visit began to ebb, black clouds began to build on the horizon. Wak-a-dah-ha-hee was still on duty. In an instant, his shield was on his arm and his bow drawn. He commanded the cloud to come nearer, “that he might draw down its contents upon the heads and the corn-fields of the Mandans!” (1:156). Finally, with the black clouds lowering, he fired an arrow into the sky, exclaiming to the assembled throng, “My friends, it is done! Wak-a-dah-ha-hee’s arrow has entered that black cloud, and the Mandans will be wet with the water of the skies!” (1:156–157). The ensuing deluge, which continued until midnight, saved the corn crop while proving the power and the efficacy of his medicine. It identified him as a man of great and powerful influence and entitled him to a life of honor and homage.

Catlin draws two lessons from this story. First, “when the Mandans undertake to make it rain, they never fail to succeed, for their ceremonies never stop until rain begins to fall” (1:157). Second, the Mandan rainmaker, once successful, never tries it again. His medicine is undoubted. During future droughts, he defers to younger braves seeking to prove themselves. Unlike Western, technological rainmaking, in Mandan culture the rain chooses the rainmaker.

Leavers and Takers

In his imaginative book Ishmael (1992), Daniel Quinn draws a basic distinction between two major streams in human culture: the Takers (the heirs of the...