![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction: Pilgrimage as a Liminoid Phenomenon

PILGRIMAGES are probably of ancient origin and can, indeed, be found among peoples classed by some anthropologists as “tribal,” peoples such as the Huichol, the Lunda, and the Shona. But pilgrimage as an institutional form does not attain real prominence until the emergence of the major historical religions—Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In view of its importance in the actual functioning of these religions, both quantitatively and qualitatively, pilgrimage has been surprisingly neglected by historians and social scientists. But perhaps it has merely shared in the general disregard of the liminal1 and marginal phenomena of social process and cultural dynamics by those intent either upon the description and classification of orderly institutionalized “facts” or upon the establishment of the “historicity” of prestigious, unrepeated events.

It was Arnold van Gennep (1908; 1960), the French folklorist and ethnographer neglected by the pundits, savants, and mandarins of the French school of sociology in his own time, who gave us the first clues about how ancient and tribal societies conceptualized and symbolized the transitions men have to make between well-defined states and statuses, if they are to grow up to accommodate themselves to unprecedented, even antithetical conditions. He showed us that all rites de passage (rites of transition) are marked by three phases: separation, limen or margin, and aggregation. The first phase comprises symbolic behavior signifying the detachment of the individual or group, either from an earlier fixed point in the social structure or from a relatively stable set of cultural conditions (a cultural “state”); during the intervening liminal phase, the state of the ritual subject (the “passenger” or “liminar”) becomes ambiguous, he passes through a realm or dimension that has few or none of the attributes of the past or coming state, he is betwixt and between all familiar lines of classification; in the third phase the passage is consummated, and the subject returns to classified secular or mundane social life. The ritual subject, individual or corporate (groups, age-sets, and social categories can also undergo transition), is again in a stable state, has rights and obligations of a clearly defined structural type, and is expected to behave in accordance with the customary norms and ethical standards appropriate to his new settled state.

By identifying liminality Van Gennep discovered a major innovative, transformative dimension of the social. He paved the way for future studies of all processes of spatiotemporal social or individual change. For liminality cannot be confined to the processual form of the traditional rites of passage in which he first identified it. Nor can it be dismissed as an undesirable (and certainly uncomfortable) movement of variable duration between successive conservatively secure states of being, cognition, or status-role incumbency. Liminality is now seen to apply to all phases of decisive cultural change, in which previous orderings of thought and behavior are subject to revision and criticism, when hitherto unprecedented modes of ordering relations between ideas and people become possible and desirable. Van Gennep made his discovery in relatively conservative societies, but its implications are truly revolutionary. In the liminality of tribal societies, traditional authority nips radical deviation in the bud. We find there symbolic inversion of social roles, the mirror-imaging of normative secular paradigms; we do not find open-endedness, the possibility that the freedom of thought inherent in the very principle of liminality could lead to major reformulation of the social structure and the paradigms which program it. But in the limina throughout actual history, when sharp divisions begin to appear between the root paradigms which have guided social action over long tracts of time and the antiparadigmatic behavior of multitudes responding to totally new pressures and incentives, we tend to find the prolific generation of new experimental models—utopias, new philosophical systems, scientific hypotheses, political programs, art forms, and the like—among which reality-testing will result in the cultural “natural selection” of those best fitted to make intelligible, and give form to, the new contents of social relations.

It has become clear to us that liminality is not only transition but also potentiality, not only “going to be” but also “what may be,” a formulable domain in which all that is not manifest in the normal day-to-day operation of social structures (whether on account of social repression or because it is rendered cognitively “invisible” by prestigious paradigmatic denial) can be studied objectively, despite the often bizarre and metaphorical character of its contents. In The Ritual Process (V. Turner 1969), certain modes of liminality in preindustrial society were examined, and further studies in more developed cultures were suggested. The present book is an attempt to examine in some detail what we consider to be one characteristic type of liminality in cultures ideologically dominated by the “historical,” or “salvation,” religions.

When we first began to look for ritual analogues between “archaic,” or “tribal,” and “historical” religious liminality, beginning with the Catholic Christian tradition which we know best, we turned, naturally enough, to the ceremonies of the Roman rite. But in the liturgical ceremonies of the Mass, baptism, female purification, confirmation, nuptials, ordination, extreme unction, and funerary rituals, though it was possible to discern somewhat truncated liminal phases, we found nothing that replicated the scale and complexity of liminality in the major initiation rituals of the tribal societies with which we were familiar. One obvious difference was seen in the spatial location of liminality. In many tribal societies, initiands are secluded in a sacralized enclosure, or temenos, clearly set apart from the villages, markets, pastures, and gardens of everyday usage and trafficking (see Junod 1962: vol. 1, pp. 74–94; Wilson 1957:86–129; Richards 1957; Turner 1968:210–39; Barth 1975:47–102). But in the “historical” religions, comparable seclusion has been exemplified only in the total life-style of the specialized religious orders. In other words, the progressive division of labor made of the liminal phase a specialized state, complex and intense enough to involve the entire lives of the deeply devoted. Of course, as the history of monasticism has shown, the orders become decreasingly liminal as they enter into manifold relations with the environing economic and political milieus. That, however, is matter for a different book. But the religious, though relatively numerous in the heyday of the historical religions, were easily outnumbered by the ordinary worshipers, the peasants and the citizens. Where was their liminality? Or was there indeed any liminality for them at all?

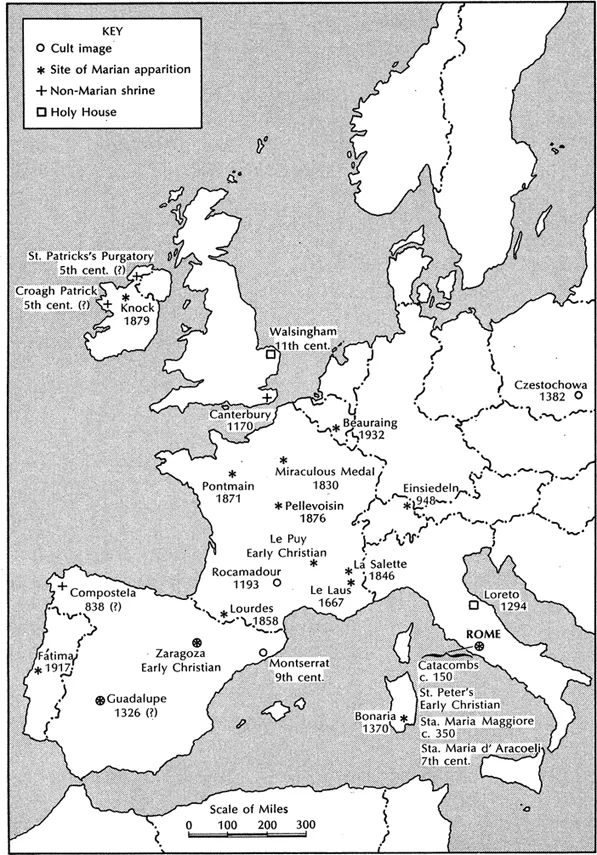

In European societies with a rurally based economy and feudal political structures, life for the masses tended to be intimately localized. Indeed, for Christian serfs and villeins the law itself ordained their attachment to particular manors or demesnes. Their religious life was also locally fixated; the parish was their spiritual manor. Yet during its development, Christianity generated its own mode of liminality for the laity. This mode was best represented by the pilgrimage to a sacred site or holy shrine located at some distance away from the pilgrim’s place of residence and daily labor. Beginning with the pilgrimage to remote Jerusalem (Palestine Pilgrims’ Text Society, 1887; 1889; 1891a,b,c; 1893)—made by a few choice, pious, and relatively well-to-do persons—to which was swiftly joined the pilgrimage to the shrines of Peter and Paul in Rome (Jusserand 1891:374–78; Sigal 1974:99–110), the map of Europe, particularly after the Saracenic occupation of the Holy Land and domination of the Mediterranean sea routes thither, came to be crisscrossed with pilgrim ways and trails to the shrines of European saints and advocations of the Holy Virgin (varieties of mode of address, such as Our Lady of Walsingham) and to churches containing important relics of Christ’s ministry and passion (Turner 1974a: 224–26). Such pilgrim centers and ways, frequented increasingly by the poor, can be regarded as a complex surrogate for the journey to the source and heartland of the faith.

MAJOR EUROPEAN PILGRIMAGE SHRINES

The pilgrim trails cut across the boundaries of provinces, realms, and even empires (Jusserand 1891:362–71, 393–95). In each nascent nation certain shrines became preeminent centers of legitimate devotion. But since the church laid claim to universality, pilgrims were encouraged to take up staff and scrip to travel to the great shrines in other Christian lands. In time this international religious tourist traffic became organized. (Venice became the model for later secular tourism, as well as for modern agencies of pilgrim travel.)2 Many Englishmen made the pilgrimage to St. James the Apostle’s shrine in Spain, while French and Dutch pilgrims swarmed across the Channel to visit St. Thomas’s tomb at Canterbury. Within each country one can detect a loose hierarchy, or at least a rough scale of priorities, among its shrines. In plural societies, each linguistic or ethnic group has its favored pilgrimage places. Provinces, districts, even the shrines themselves, have their focal devotions. All sites of pilgrimage have this in common: they are believed to be places where miracles once happened, still happen, and may happen again. Even where the time of miraculous healings is reluctantly conceded to be past, believers firmly hold that faith is strengthened and salvation better secured by personal exposure to the beneficent unseen presence of the Blessed Virgin or the local saint, mediated through a cherished image or painting. Miracles or the revivification of faith are everywhere regarded as rewards for undertaking long, not infrequently perilous, journeys and for having temporarily given up not only the cares but also the rewards of ordinary life. Behind such journeys in Christendom lies the paradigm of the via crucis, with the added purgatorial element appropriate to fallen men. While monastic contemplatives and mystics could daily make interior salvific journeys, those in the world had to exteriorize theirs in the infrequent adventure of pilgrimage. For the majority, pilgrimage was the great liminal experience of the religious life. If mysticism is an interior pilgrimage, pilgrimage is exteriorized mysticism.

The point of it all is to get out, go forth, to a far holy place approved by all. In societies with few economic opportunities for movement away from limited circles of friends, neighbors, and local authorities, all rooted alike in the soil, the only journey possible for those not merchants, peddlers, minstrels, jugglers, tumblers, wandering friars, or outlaws, or their modern equivalents, is a holy journey, a pilgrimage or a crusade. On such a journey one gets away from the reiterated “occasions of sin” which make up so much of the human experience of social structure. If one is tied by blood or edict to a given set of people in daily intercourse over the whole gamut of human activities—domestic, economic, jural, ritual, recreational, affinal, neighborly—small grievances over trivial issues tend to accumulate through the years, until they become major disputes over property, office, or prestige which factionalize the group. One piles up a store of nagging guilts, not all of which can be relieved in the parish confessional, especially when the priest himself may be party to some of the conflicts. When such a load can no longer be borne, it is time to take the road as a pilgrim.

For many pilgrims the journey itself is something of a penance. Not only may the way be long, it is also hazardous, beset by robbers, thieves, and confidence men aplenty (as many pilgrim records attest), as well as by natural dangers and epidemics. But these fresh and unpredictable troubles represent, at the same time, a release from the ingrown ills of home. They are not one’s own fault, though they may be sent by the Almighty to try one’s moral mettle. (There are, of course, legends that very bad sinners will have extra trouble on their pilgrimage. One cycle of stories, for example, recounts the mishaps on the penitential pilgrimage to Jerusalem by the four knights who martyred St. Thomas Becket. Finally, so the tale runs, persistent offshore gales prevented them from setting foot on the Holy Land, and they had to return, as it were, unforgiven.)

Although the pilgrim may take the path because he has made a promise to a saint whose intercession he once sought on his own or a beloved’s behalf, nevertheless it is he who decides on the day and hour of his going. This freedom of choice in itself negates the obligatoriness of a life embedded in social structure. In many tribal societies, on the other hand, rituals such as initiation, which contain extended liminal phases, tend to be obligatory. Nearly everyone has to pass through certain main-stem rites. There is some room for choice, certainly, but it is usually confined to such questions as the precise timing and placement of corporate performance rather than to whether an individual is willing to undergo the ritual at all. Often, too, it is left to complex divinatory procedures to determine when and where rites should take place; thus the scope of individual choice is further narrowed. Of course, some religious pilgrimages, like the hajj in Islam, are defined as a duty incumbent on all believers. But in such cases there are so many qualifying clauses and extenuating circumstances that the individual is placed once more in a situation of virtual choice.

Yet there is undoubtedly an initiatory quality in pilgrimage. A pilgrim is an initiand, entering into a new, deeper level of existence than he has known in his accustomed milieu. Homologous with the ordeals of tribal initiation are the trials, tribulations, and even temptations of the pilgrim’s way. And at the end the pilgrim, like the novice, is exposed to powerful religious sacra (shrines, images, liturgies, curative waters, ritual circumambulations of holy objects, and so on), the beneficial effect of which depends upon the zeal and pertinacity of his quest. Tribal sacra are secret; Christian sacra are exposed to the view of pilgrims and ordinary believers alike. Again, the mystery of choice resides in the individual, not in the group. What is secret in the Christian pilgrimage, then, is the inward movement of the heart. In tribal rituals, on the other hand, what is concealed from the profane—the sacred objects and teachings—is the possession of an elite group within the community, whether this be, for example, an inner core of initiated men or a nuclear group of mothers and potential mothers. In the pilgrimages of the historical religions the moral unit is the individual, and his goal is salvation or release from the sins and evils of the structural world, in preparation for participation in an afterlife of pure bliss. In tribal initiation the moral unit is the social group or category, and the goal is the attainment of a new sociocultural status and state. While the pilgrim seeks temporary release from the structures that normally bind him, the tribal initiand seeks a deeper commitment to the structural life of his local community, ultimately, in many cases, to the state of being a venerated, legitimate ancestor after death, rather than a homeless ghost. Of course, historically the distinction has not always been so clearcut. Pilgrims sometimes enhance their mundane status through having made the journey. And in tribal religions certain kinds of initiation, notably the shamanic and the priestly, frequently offer a measure of release from the duties and necessities of the structural order, and a measure of participation in the invisible milieu of the gods or ancestors. Robert F. Gray (1963:14) has described how the Khambageu cult among the Sonjo of Tanzania promises salvation for believers who have undergone a specific initiation rite. Jacques Maquet (1954:183–84) mentions a similar cult in Ruanda. We must also face the fact of an opposite tendency in the historical religions, where the community of believers has often acquired something of a tribal character, on a world scale, and where religious wars are, as it were, magnified tribal feuds. While politics and economics become increasingly international and noncorporate as markets, merchants, and cities multiply, salvation religions, though universal in principle, raise corporate walls against outsiders in practice. This exclusiveness is reflected in the pilgrimage systems. With rare and interesting exceptions, the pilgrims of the different historical religions do not visit one another’s shrines, and certainly do not find salvation extra ecclesia. Pilgrimage, then, offers liberation from profane social structures that are symbiotic with a specific religious system, but they do this only in order to intensify the pilgrim’s attachment to his own religion, often in fanatical opposition to other religions. That is why some pilgrimages have become crusades and jihads. Nevertheless, within the institution of pilgrimages, human freedom made a historic advance. Inside the Christian religious frame, pilgrimage may be said to represent the quintessence of voluntary liminality. In this, again, they follow the paradigm of the via crucis, in which Jesus Christ voluntarily submitted his will to the will of God and chose martyrdom rather than mastery over man, death for the other, not death of the other.

Toward the end of a pilgrimage, the pilgrim’s new-found freedom from mundane or profane structures is increasingly circumscribed by symbolic structures: religious buildings, pictorial images, statuary, and sacralized features of the topography, often described and defined in sacred tales and legend. Underlying the sensorily perceptible symbol-vehicles are structures of thought and feeling—ideological forms—which may be truly described as “root paradigms” (see Appendix A for a discussion of this term). These derive from the seminal words and works of the religion’s founder, his disciples or companions, and their immediate followers, and constitute the “deposit of faith.” Quite often they owe their systematic formulation to the collective deliberations of later dogmatists and theologians, who aimed at giving an institutional shape to the spontaneous insights and inspired actions of the founder. The root paradigms draw upon crises in the founder’s life—especially those of his birth, coming of age, and death—to clothe abstract patterns of relationships in vivid forms accessible, through the sympathy of common experience, to all believers. Thus we see images, icons, and paintings of Jesus as infant, child, young preacher, scourged victim, crucified scapegoat, and resurrected God-man. Each of these representations is set, however sketchily in some cases, in the context of images derived from the sacred narrative of the founder’s life. In this way, something is shown of his relations with his parents and kinsfolk, with his disciples, with strangers, with his accusers and enemies, with the anonymous people he healed or instructed, and even with supernatural beings, such as the other Persons of the Trinity, angels, and devils. Between founder and setting (those features of the natural and cultural landscape regarded as pertinent to the paradigm being expressed), there exist sets of relationships which together compose a message about the central values of the religious system. The pilgrim, as he is increasingly hemmed in by such sacred symbols, may not consciously grasp more than a fraction of the message, but through the reiteration of its symbolic expressions, and sometimes through their very vividness, he becomes increasingly capable of entering in imagination and with sympathy into the culturally defined experiences of the founder and of those persons depicted as standing in some close relationship to him, whether it be of love or hate, loyalty or awe. The trials of the long route will normally have made the pilgrim quite vulnerable to such impressions. Religious images strike him, in these novel circumstances, as perhaps they have never done before, even though he may have seen very similar objects in his parish church almost every day of his life. The innocence of the eye is the whole point here, the “cleansing of the doors of perception.” Pilgrims have often written of the “transformative” effect on them of approaching the final altar or the holy grotto at the end of the way. Purified from structural sins, they receive the pure imprint of a paradigmatic structure. This paradigm will give a measure of coherence, direction, and meaning to their action, in proportion to their identification with the symbolic representation of the founder’s experiences. For them the founder becomes a savior, one who saves them from themselves, “themselves” both as socially defined and as personally experienced. The pilgrim “puts on Christ Jesus” as a paradigmatic mask, or persona, and thus for a while becomes the redemptive tradition, no longer a biopsychical unit with a specific history—as in tribal initiations, where the individual who dons the ceremonial mask becomes for a while the god or power signified by the mask and the costume linked to it. But since Christ signifies “the individual” (he represents uniqueness for everyone), a fundamental difference between corporate and singular initiatory traditions is still discernible.

But pilgrimages are not merely optational equivalents of obligatory tribal initiations. They also have affinities with what have been called “rituals of affliction” (see V. Turner 1957:292; 1968:15–...