![]()

1

PUBLIC OPINION IN CHINESE FOREIGN POLICY

To speak with precision of public opinion is a task not unlike coming to grips with the Holy Ghost.

—V. O. KEY, PUBLIC OPINION AND AMERICAN DEMOCRACY

Defining public opinion has never been easy. Harwood Childs compiled four dozen different definitions, describing the field as “strewn with zealous attempts.”1 Susan Herbst simply gave up, deciding to “avoid discovering the true meaning of the phrase and simply grant that the definition is fluid.”2 Rarely in the social sciences has such a fundamental concept been so thoroughly contested. Floyd Allport, writing in the inaugural edition of Public Opinion Quarterly in 1937, warned against “the illusion that the item one sees in print as ‘public opinion’ … really has this character of widespread importance and endorsement.”3 In 1922 Walter Lippmann described a “phantom public,” arguing that public opinion was essentially a self-serving rhetorical construction created by elites.4 More recently, Pierre Bourdieu claimed:

Public opinion, in the sense of the social definition implicitly accepted by those who prepare or analyze or use opinion polls, simply does not exist. … The opinion survey treats public opinion like the simple sum of individual opinions gathered in an isolated situation where the individual furtively expresses an isolated opinion. In real situations opinions are forces, and relations of opinions are conflicts of forces.5

The essential problem is that most studies of public opinion have conflated one possible measure of public opinion, namely survey data, with public opinion itself. This includes most scholarship on public opinion in China.6 “These days we tend to believe that public opinion is the aggregation of individual opinions as measured by the sample survey,” explains Herbst. “This definition is now hegemonic; when most of us consider the meaning of public opinion, we can’t help but think about polls or surveys.”7 Yet by assessing public opinion only through these private interactions, survey data fails to capture any collective expression of public opinion. “The paradoxical result,” as Taeku Lee notes, “is that public opinion ceases to be public.”8

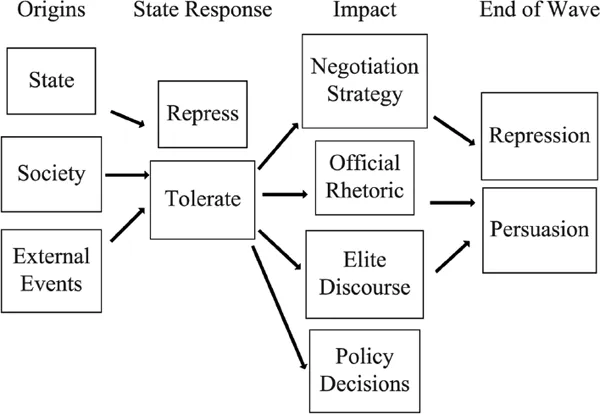

In this chapter, I develop an alternative approach to understanding the role of public opinion in authoritarian states’ foreign policy, based on the concept of a wave of public mobilization.9 A wave of popular mobilization consists of a rapid shift in public opinion and popular emotions, growing political activism, and expanded sensationalist coverage in popular media and on the Internet. Such a wave can arise from society, the state, and/or external events, but once it does, the state must decide to respond with either tolerance or repression. If government officials allow or even encourage protests and activism, then popular pressure may influence negotiating strategy, official rhetoric, elites’ public discourse, and foreign policy decisions. Yet once popular activism begins to threaten core foreign policy interests and undermine social stability at home, authoritarian leaders tend to respond with a mixture of repression and persuasion. One payoff of this approach is that we can examine public mobilization both as a dependent variable, assessing the relative role of state and society in causing public mobilization, and as an independent variable, measuring the public’s influence on foreign policy decisions and discourse.

More broadly, this approach helps address one of the central questions of Chinese politics today: how does the world’s largest and most powerful Communist Party, dedicated to constructing a “harmonious society,” maintain its authority over a society rife with tension and contention? The common presumption is that popular protests in China reflect regime weakness.10 Yet rather than revealing the vulnerability of the CCP, popular expressions of emotion on the streets, online, and in the media may actually play a role in sustaining Party authority and legitimacy. Protests provide the leadership with information on relevant aspects of popular sentiments. They also serve as a release valve, directing popular anger toward a foreign country rather than at the CCP itself. By responding to public expressions of anger with symbolic or partial policy shifts, Chinese leaders can demonstrate their responsiveness to the people’s concerns, thus alleviating potential criticism from some of the most mobilized segments of society. A number of scholars have argued that the CCP tolerates nationalist protests and responds to public pressure out of weakness. They warn that Beijing may feel compelled to follow the dictates of an emotional public by adopting a more aggressive foreign policy.11 Instead, I see protests over foreign relations as fundamentally cyclical—following a familiar pattern of rapid swells of anger and activism that may influence policy decisions and discourse, but then quickly recede. The state’s capacity to bring about the end of a wave of protests through a mixture of repression and persuasion provides valuable insight into state strength.

This first chapter develops the conceptual framework used to guide the remainder of the study. I first describe the origins of public mobilization, examining the three elements of public opinion, popular activism, and popular media, and explore interactive effects among them. I then turn to interactions between public mobilization and the state, laying out the conditions under which authoritarian states are likely to tolerate and respond to popular mobilization. The third section compares the role of state and societal factors in ending a wave. In developing the concept of a wave of popular mobilization, I draw together approaches typically used in isolation: studies of the role of public opinion in democracies’ foreign policy, studies of social movements, and comparative foreign policy studies. Each offers distinct methodologies and insights that, when combined, help us piece together the role of public opinion in authoritarian states’ foreign policy.

THE RISE OF PUBLIC MOBILIZATION

Mobilization was a pillar of Maoist rule. As Elizabeth Perry notes, “Communist China parts company with classic authoritarianism in having periodically encouraged—indeed compelled—its citizens to express their private criticisms publicly in the form of big-character posters, struggle sessions, denunciation meetings, demonstrations and the like. The Cultural Revolution was the most dramatic, but not the last, expression of this state-sponsored effort at stimulating and shaping confrontational politics.”12 In the mobilization model developed under Mao Zedong, instructions were first issued through an official government document or in an editorial or commentator’s essay in the Party’s flagship paper, the People’s Daily. Detailed instructions were then disseminated throughout the political system according to cadres’ rank order. People were brought together in study groups to discuss the campaign, and then organized in activities to implement the agenda. State-led mobilization, while less frequent than under Mao, has hardly been abandoned in the reform era. Since 1978, the state has relied on mobilization to introduce the one-child policy, promote economic reforms in urban enterprises, restructure the labor system, and embark upon a nationwide reform of urban health insurance.13

Focusing instead on popular mobilization opens up the possibility of weighing the influence of state and society. A wave of public mobilization consists of a shift in public attitudes, as measured through poll data, combined with a rise in sensationalist media coverage and instances of activism. The wave tends to come in four stages (see figure 1.1). It can be initiated and spread by elements within the state, by factors outside of the state, by external events, or most likely, by interactions among all three. Once public mobilization begins, authoritarian leaders are pressed into a gatekeeper role, quickly forced to decide whether to tolerate or repress early instances of popular activism and sensationalist media coverage. Tolerance is particularly likely at points when public emotions are high, bilateral relations are acrimonious, and top leaders are divided over foreign policy. Opening the gates to popular protests and sensationalist media coverage allows the wave to spread. If it grows, public mobilization can impede diplomatic negotiations, spur belligerent rhetoric, influence public discourse among policy experts, and obstruct policy makers’ efforts to pursue a conciliatory foreign policy.

Paradoxically, the escalation of public mobilization also contains the seeds of its demise. As protests and anger spread, the costs of tolerance begin to loom large for political leaders. Domestic instability threatens. Nuanced foreign policy strategies are undermined by following the dictates of an angry public. In response, policy makers are likely to try to reverse course, relying upon a mixture of repression and persuasion to constrain the media, curtail popular protests, and reshape public opinion. These three elements then begin to work in reverse. As media coverage shifts and political activism declines, public attention moves elsewhere. Emotions cool and people’s attitudes become more flexible and moderate. In this calmer environment, even sporadic acts of protest or occasional sensationalist stories are unlikely to spark widespread public anger or debates. The public soon returns to a more familiar state of quiescence, marked by inattention to foreign policy issues. The wave of public mobilization has come to an end.

Public mobilization may begin with a small event but then, like a snowball rolling downhill, gather greater force as it picks up speed and mass. A supportive public provides a market incentive for sensationalist media coverage and broadens popular participation in protest activities. Media coverage and dramatic acts of activism further heighten issue awareness and popular emotions, encouraging people to form opinions on an issue that they may have previously ignored. To understand these interactive effects, we need to draw together theories typically used in isolation to study social movements, popular media, and public opinion.

FIGURE 1.1 Stages in a Wave of Public Mobilization

The Problem with Public Opinion

Three questions have challenged studies of public opinion for decades: how to define public opinion, how to measure it, and how to decide whose opinions matter. Scholars have long assumed that public opinion in authoritarian states is an oxymoron—a logical impossibility due to the lack of individual freedoms. Hans Speier defined public opinion as “opinions on matters of concern to the nation freely and publicly expressed by men outside of the government who claim a right that their opinions should influence or determine the actions, personnel, or structure of their government.”14 For this reason, Jurgen Habermas’ influential study explicitly “limits the treatment of public opinion to countries of Western Europe and North America in the last two centuries.”15 More recently, however, scholars have adopted broader conceptions. Bernard Berelson defines public opinion simply as “people’s response (that is, approval, disapproval, or indifference) to controversial political and social issues of general attention,” while Ithiel de Sola Pool simply requires that opinions are publicly expressed, relate to public affairs, and held by the general public.16 A related problem is identifying whose opinions matter. Scholars have traditionally distinguished between the general or mass public and what Gabriel Almond called the “attentive public … which is informed and interested in foreign policy problems, and which constitutes the audience for foreign policy elites.” Almond ranked ever-smaller segments of the U.S. public according to their significance—active publics, issue publics, and finally the elite.17 Phillip Converse simply distinguished “two faces of public opinion”: a general set of attitudes identified by surveys and the “effective public opinion,” evidenced by atmospherics in the news media and influence on political outcomes.18

These efforts to isolate segments of the public are based upon the presumption that elite segments are more likely to influence policy outcomes. Yet for authoritarian states such as China, general public opinion provides a base of potential support for activists and commercial media, serving as an incentive for certain kinds of media stories and providing potential participants in broader protest efforts (particularly activities with low entry thresholds, such as online petition campaigns). In addition, as I will discuss below, authoritarian leaders are likely to be particularly concerned about broad popular sentiments due to the potential for mass protests. This book spotlights three aspects of general public opinion as particularly significant in authoritarian states: levels of public emotion, the public’s attention to an issue or “issue activation,” and the content of individual attitudes, positions, or beliefs on a given issue. These attributes tend to run together: as the public becomes aware of a given issue, they are more likely to develop and express opinions and emotions on it. High levels of issue awareness and issue activation are likely to correspond with greater public influence on policy.19

Perhaps the greatest challenge comes in measuring public opinion. In the 1920s, George Gallup embarked upon polling in the United States as a more scientific and democratic way of assessing public opinion. Yet numerous studies have shown that slight changes in question content, format, and ordering, and even the survey venue, can yield dramatically different results. These results can then be presented in a selective manner to advance a particular perspective. For Justin Lewis, polls are used to “construct,” not measure, public opinion. “Polls function,” Lewis argues, “to structure opinions into forms measurable against elite discourse.” They simplify and structure individuals’ complex attitudes and beliefs into ordered responses that, when amalgamated, purport to represent the popular will. Publishing poll results in mass media presents the appearance of a single, majority c...