![]()

1

Financial Crisis Origin

A variety of factors contributed to the U.S. economy’s recession, which exhibited catastrophic symptoms of a housing bubble toward the end of 2007. Prompted by low interest rates beginning on January 3, 2001, and overlooked by the regulatory agencies, Americans borrowed excessively for home mortgages. This first phase of extensive mortgage financing for eventual home ownership extended from 2001 to 2004. Then from June 30, 2004, interest rates began moving up and these mortgages became unmanageable and ultimately subprime. Marked by escalating foreclosures, this second phase of their conversion into the subprime category intensified from 2005 to 2007. The crashing valuations of mortgage-based assets held by U.S. financial institutions, among them government-supported Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and by the American Insurance Group (AIG), required their bailout by the Treasury and the Federal Reserve in late September 2008.

These subprime mortgages were also repackaged into salable assets by savvy operators who sold them to investors, which included large Wall Street banks. This securitization activity via slicing and dicing of the troubled mortgages intensified in 2007. When brought into the act, Congress passed a $700 billon Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) for rescuing the banking system.

A major financial breakdown was avoided.

The housing bubble, financed by excessive mortgage lending that plunged the U.S. financial sector into a severe crisis, required its bailout in late 2008 and early 2009. To understand this unprecedented rescue operation, it is necessary to examine the U.S. economy’s recovery from the March 2000 collapse of the dotcom bubble.

I. Easy Monetary Policy and Tax Cuts

Beginning in January 2001, the Federal Reserve followed an easy monetary policy for pulling the economy out of the recession that was induced by the collapse of the dotcom bubble in March 2000. It lowered the federal funds rate—which sets the overnight interbank borrowing cost—from 6 to 1 percent on January 3, 2001, and kept it there until June 30, 2004. At the same time, tax cuts, proposed by President George W. Bush and approved by Congress in 2001 and 2003, provided the fiscal stimulus.

Americans began acquiring low-interest-rate mortgages to buy homes. The housing boom, feeding into vigorous construction activity from 2001, provided the impetus to economic recovery, which gathered momentum in 2003 and 2004. The economy recorded a 2003 third quarter GDP growth of 7.5 percent over the preceding quarter. GDP growth rate in 2004 was an exceptional 3.6 percent.

An external factor, combined with the easy monetary policy from 2001 through June 2004, added to the continuing economic resurgence marked by the housing bubble.

Saving Flow from Outside

The emergence of China as a fast-growing economy, with a real annual GDP growth of 8 to 10 percent starting in 1980, represented a new phenomenon in the history of the modern world. By 2005, China’s gross domestic investment at 41.2 percent of its GDP was exceeded by its gross saving rate at 49.5 percent, with the rising profitability of the Chinese corporate sector accounting for 70 percent of these savings.1 At the same time, a booming export sector contributed to the double-digit annual GDP growth of 10 to 11 percent from 2003 to 2006. The People’s Bank of China aggressively pumped Chinese currency into the foreign exchange market in exchange for dollars from exporters, which it invested in U.S. Treasury bonds and other foreign currency holdings.2

This generous bounty implied that the U.S. Treasury had to borrow less internally. U.S. mortgage rates, steered by the federal funds rate of 1 percent, remained low, which encouraged Americans to take on massive mortgages for home ownership. These mortgages turned into unsustainable burdens as the Federal Reserve began raising the federal funds rate after June 30, 2004. The rate rose to 5.25 percent by June 29, 2006, where it remained until August 17, 2007.

The process of unconstrained home ownership was aided by the failure of consumer protection arrangements that were encumbered by the presence of several agencies responsible for protecting house hold interests by ensuring regulatory compliance on the part of brokers, mortgage companies, and banks. This is examined in the next section.

II. Failure of Regulatory Arrangements

In the years leading to the crisis, Wall Street banks, flush with cash, were eager to acquire mortgage-backed securities. They encouraged mortgage companies and brokers by steering potential borrowers into high-risk loans. People borrowed beyond their means because appraisers inflated the values of properties that prospective buyers were interested in. Borrowers were led to believe that they had undertaken a standard fixed-rate mortgage only to learn later that their mortgage was a complicated variable-rate contract. Banks could choose their own regulators and switch to a less scrupulous regulator. Federal regulators occasionally sidestepped tougher state requirements that could have prevented such predatory lending activities. Hardly anyone debated the “regulatory capture” by the federal agencies while risky lending practices proliferated.

Mortgage-securitizing banks were not responsible for abuses in the original mortgages. Large American and European banks securitized these subprime mortgages and sold them to global investors with a view to making a profit.

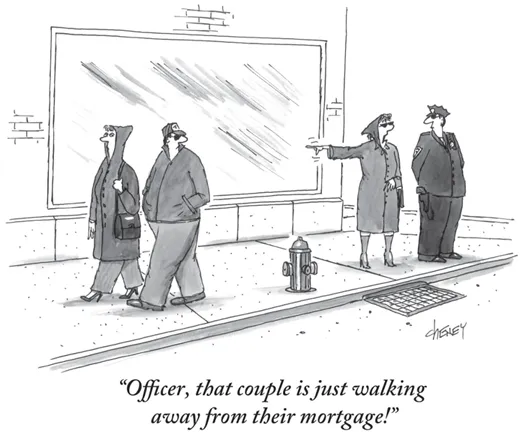

According to the Center for Public Integrity, the top 25 subprime originators had advanced almost $1 trillion in loans to more than 5 million borrowers between 2005 and 2007, the peak of subprime lending. Many of these borrowers’ homes were eventually repossessed.3

(© Tom Cheney/The New Yorker Collection /http://www.cartoonbank.com.)

Would you pay $103,000 for this Arizona fixer-upper? (Reprinted by permission of The Wall Street Journal, copyright © 2009 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide.)

Among mortgage firms that had recklessly extended loans to home owners was Integrity Funding LLC, which had given a $103,000 home equity loan in early 2007 to Marvene Halterman for a little blue house on West Hopi Street in Avondale, Arizona. It was a 30-year mortgage with an adjustable rate that started at 9.25 percent and was capped at 15.25 percent.4 Halterman, who had bought the house four decades earlier for $3,500, had a long history of unemployment and other problems. She collected junk, and the yard at the house “was waist high in clothes, tires, laundry baskets and broken furniture.… By the time the house went into foreclosure in August [2009], Integrity had sold that loan to Wells Fargo & Co., which had sold it to a U.S. unit of HSBC Holdings PLC, which had packaged it with thousands of other risky mortgages and sold it in pieces to scores of investors.”5 A series of similar out-of-bounds decisions had set the stage for the unfolding of the worst financial crisis to hit the United States since the Great Depression.

Why was mortgage lending not regulated? According to the Center for Public Integrity, the big financial players spent $3.5 billion lobbying Washington from 2000 to 2009 and donated $2.2 billion to political campaigns. Wells Fargo Financial, owned by the bank, contributed almost $18 million to election campaigns and lobbying, equally divided between Republicans and Democrats.6

(City of Avondale, AZ; Code Enforcement Division.)

Would the crisis have been averted if mortgage lenders’ risk management and underwriting practices were more effectively regulated despite the Fed’s low interest rate policy from 2001 to 2006? The next section explores this question.

III. What Caused the Crisis:

Lax Regulations or Easy Monetary Policy?

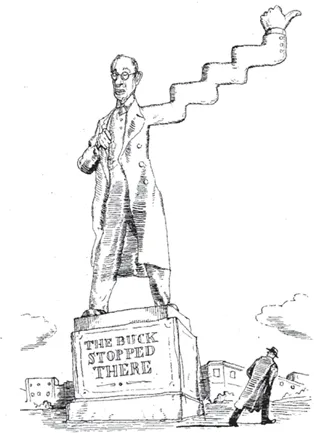

Alan Greenspan, who was chairman of the Federal Reserve from 1987 to 2006, was grilled by the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission on April 7, 2010, about the Fed’s role in the onset of the crisis. Didn’t the Fed’s failure to curb subprime lending amid the unfolding of the housing bubble fall into the category of “oops”? Phil Angelides, commission chairman, reiterated: “My view is you could have, you should have, and you didn’t.”7 Defending his record, the former chairman said: “I was right 70 percent of the time, but I was wrong 30 percent of the time. What we tried to do was the best we could with the data that we had.”8 Referring to the ballooning subprime mortgages, he said: “If the Fed … had tried to thwart what everyone perceived as … an unmitigated good, then Congress would have clamped down on us.” Then again: “If we had said we’re running into a bubble [of house prices] and we need to retrench, the Congress would say, ‘We haven’t a clue what you’re talking about.’”9

(© 2010, Barry Blitt. Reprinted by permission.)

The Fed chairman’s policy handling prompted this response from a New York Times columnist: “If the captain of the Titanic followed the Greenspan model, he could claim he was on course at least 70 percent of the time too.”10

Current Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke also defended the Fed’s record by distinguishing between regulatory failure and low interest rates as factors contributing to the housing bubble. The easy interest rate regime prevailed from 2001 to 2006—he was a member of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve for most of that period. In his remarks at the annual meeting of the American Economic Association in early January 2010, he said: “When historical relationships are taken into account, it is difficult to ascribe the house price bubble either to monetary policy or to the broader macroeconomic environment.”11 Earlier Bernanke had referred to the flow of saving from China that had kept U.S. interest rates low. Wasn’t it necessary therefore to moderate the Fed’s easy monetary policy?

Alicia H. Munnell, a former research director at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, provided an insightful assessment: “The Fed is this powerful and privileged institution, and it has a bully pulpit that it can use even when it doesn’t have the direct authority to regulate … it’s never appropriate for a Federal Reserve official to say, ‘It’s not our job.’ In some ways, Alan Greenspan is saying that.”12 Clearly the Federal Reserve, in charge of the financial regulatory setup, should have been aware of its massive policy shortcomings. Wouldn’t the borrowing binge have been moderated or even cut short if it had raised the federal funds rate earlier and adequately? Weren’t community banks around the country, which issued mortgages and chose their own regulators for the purpose, under the supervisory umbrella of the Federal Reserve? At the same time, shouldn’t the Securities and Exchange Commission have extended its regulatory oversight to the activities of financial institutions that were recklessly packaging these subprime mortgages and selling them to investors, which included large Wall Street banks?

In any case, while the Fed defaulted in its policy-making and regulatory roles, were banks poised to manage the hit from the subprime mortgage holdings in their portfolios? Let’s examine that question.

IV. Consequences of Excessive Securitization of

Subprime Mortgages by Banks

Bank holdings of securitized mortgages were diversified across regions of the United States. One region may suffer a crash, but the property market would not collapse across the country as a whole. Besides, in the first half of 2007, large western banks had posted a record $425 billion in aggregate profits and had capital reserves that vastly exceeded the minimum required by international banking rules. Global banks alone were estimated to hold core capital (known as tier 1) of $3.4 trillion against their assets.

However, losses on the securitized mortgage assets turned out to be so large in the second half of 2007 that they started eating up bank capital. Between June and late November of 2007, more than $240 billion had been wiped off the market capitalization of the 12 largest Wall Street banks. Banks stopped trusting one another. They refused to lend to one another and hoarded their cash.

As the cash shortage intensified, New York, London, and Zurich bankers sought capital infusions from Asian and Middle Eastern sovereign funds estimated at about $3 trillion. Citigroup Inc. was the first to get an infusion, in late November 2008, of $7.5 billion from the Abu Dhabi Investment Fund, the world’s biggest sovereign fund. UBS and Merrill Lynch followed.

The crisis of confidence—the loss of “animal spirits”—affected not only the banking sector, but also the stock market, the Treasury bond market, and, most of all, American households struggling with the burden of mortgage payments and home foreclosures as 2007 wound down. In a parallel to the stock market crash of 1929, the market experienced its worst week in October 3. The interest rates on three-month U.S. Treasury bills veered into the negative range in September 2008, for the first time since 1941. Caught in this erosion of animal spirits, American consumers cut back their spending. Business and consumer confidence needed to be revived.

It was time for the Federal Reserve to act. On January 21, 2008, Martin Luther King Day, Chairman Bernanke convened a videoconference of the Federal Open Market Committee and convinced the committee to opt for a king-sized rate cut of three-quarters of a percentage point to 3.50 percent, with a decisive hint of more to come. “It was the first time the Fed had cut rates in between regularly scheduled meetings since the aftermath of September 11, 2001. Although no one realized it at that time, Mr. Bernanke’s new strategy was born that day. Whatever it takes.”13

As 2008 advanced, the stock market began its volatile and sharp descent from a height of 13,000 (registered by the Dow Jones Industrial Average) in April 2008 to 6,500 in February 2009. At the same time, accelerating home foreclosures and subprime mortgages took a toll on mortgage-based assets of banks, mortgage-lending giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and AIG, the largest American insurer. The rescue called for a joint effort on the part of the Treasury and the Fed, as we see in the next section.

V. The Joint Treasury–Fed Rescue Deals in 2008

The earliest bailout, jointly brokered by the Treasury and the Fed, related to Bear Stearns.

JPMorgan Chase Takeover of Bear Stearns

In March 2008, JPMorgan Chase & Co. bought the collapsing Bear Stearns in a deal that was brokered jointly by former Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson and Bernanke with a transfer of Bear Stearns’s troubled assets of $29 billion to the Treasury. In the aftermath of the staggering bailouts that were to follow toward the end of the year, the Bear Stearns takeover by the Treasury was a minor exercise of ownership transfer.

On September 6, the government took over mortgage-lending giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac as they teetered near collapse with a portfolio of home loans worth $5.5 trillion out of a total estimated at $10 trillion.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac Takeover by the Treasury

For over half a century, Fannie and Freddie enabled Americans to buy homes as the two agencies purchased loans from mortgage banks and provided them with cash for making more loans. It was not the purpose of Fannie and Freddie to directly extend loans to people. The two agencies had a political a...