![]()

ONE

FROM AESTHETICS TO FILM AESTHETICS

Or, Beauty and Truth Redux

ALONGSIDE THE EMERGENCE OF CINEMA, THE TURN OF THE twentieth century witnessed a proliferation of scholarship on art history and practical aesthetics. Art historians such as Heinrich Wölfflin and Alois Riegl began to exert a defining influence on the formation of art history as a discipline, and the rise of popular forms of modernism in European and American design created new audiences for domestic and everyday aesthetics in many public spheres.1 In an analysis of the influence of aesthetics on film theory, it is useful to hold simultaneously an achronological (or, better, a very capaciously historical) view, in which key ideas from throughout aesthetics and art history recur and are reiterated across the century of writing on film, and a closely historicized view, in which the specific moment of film’s emergence significantly determined the kinds of aesthetics and the particular histories of art that shaped thinking about the new medium. Thus, for example, the Kantian idea of the beautiful might underlie many accounts of cinematic value from the early twentieth century through to the present day, and contemporary debates on modernist painting might be obvious touchstones for early-twentieth-century film critics reaching to communicate ideas about form to a cultured readership. And although these examples are quite distinct, it is not always so easy or indeed desirable to separate the chronologically localized from the more diffuse causality of discursive fields. The philosophical question of aesthetics can be closely localized, and historically specific art discourses must also be understood philosophically.

This chapter aims to outline this tale of influence, focusing on what is at stake politically in film theory’s adoption of aesthetic concepts. It seeks to tease out the formation of the pretty as a (sometimes unspoken) term of exclusion, tracing the ways in which aesthetics and art history form a particular set of foundations, ways of defining aesthetic value and meaning, that are then folded into the development of film-theoretical discourses. This narrative is dauntingly long. Even ancient Greek ideas about art echo in contemporary discourse, and any account of film’s relationship to aesthetics must be able to hear these references. However, my project is precisely to strip away the sense of film’s aesthetic regime being natural or unconnected to history and ideology. A careful embedding of aesthetic ideas in their social and political contexts is equally required. My resolution to this impasse is, unsurprisingly, dialectical. As much as an ahistorical theory of aesthetic value evades its own political biases, so does the limiting horizon of the traditional historicist. The rejection of the pretty cannot be brought into focus solely by examining the immediate precursors of each discursive moment. Rather, in the manner of Walter Benjamin’s constellation, we must amass collections of objects, ideas, and images—collections that demand consideration of the historically punctual as well as the seemingly far flung, collections that arrange history differently and, because they look back from a particular perspective, are able to read history anew.2

This particular constellation centers on classical film theory and on how and what it draws from largely modern aesthetics and art history. In its most historically delineated spaces, it considers the debates on art and design that immediately preceded and surrounded writing on the first decades of cinema. But it also looks outward from this rich historical intersection: backward to a history of the visual and plastic arts that classical film theorists consistently referenced in their scholarship and forward to provide a clearer picture of the significance of certain aesthetic problematics for film studies more generally. Questions of line and color, beauty and value, realism and the nature of the cinematic are scarcely limited to classical film theory, but, as I argue, it is in this period that these aesthetic issues were produced as foundational elements of the cinematic. Moreover, I argue that at the core of this construction of the cinematic is an exclusion of the pretty.

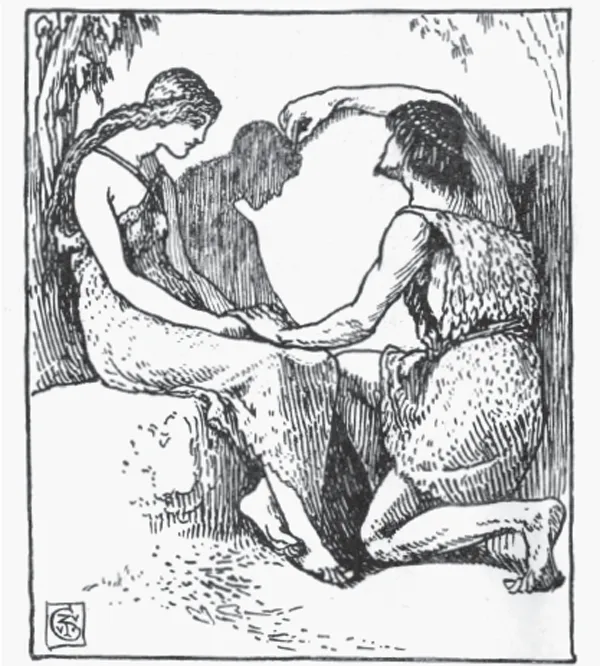

LINE AND COLOR

Walter Crane’s textbook for artists, Line and Form (1900), opens with a fascinating illustration: “The Origin of Outline” (figure 8).3 In it, a woman sits on a rock, her shadow cast on a wall behind her. Beside her, a man dressed in caveman-style fur toga uses charcoal to draw around her shadow and thus to create the first line drawing. His other hand covers her clasped hands (to reassure her or to keep her still?), while she hunches slightly in an elegant but passive pose. This illustration, although monochromatic, stages vividly the historical and political dynamics of line and color in the early twentieth century as well as the fantasmatic nature of this relationship. The woman’s body creates a block of shadow that, like color, forms an unbounded, unintentional mass, while the man turns this raw material into intended meaningful line. In a structure familiar to feminism, passive woman simply is, whereas active man creates. And although Crane’s ink drawing poses line against monochromatic shadowing rather than the polychromatic hues of painting, the allegory of the formless feminine shaped by masculine line is vividly evoked. Line and color are never mere formal terms in art historical discourse, but always already gendered, embodied, bound to socially structured hierarchies of power and value.

FIGURE 8 Walter Crane, “The Origin of Outline” (1900)

Walter Crane’s illustration figures the gendered history of drawing.

Moreover, the iconography of Crane’s allegorical image suggests the projective fantasy at work in it. Created for the book in 1900, the image nonetheless draws on two distinct levels of historicity. The first is the caveman aesthetic of the couple’s shaggy clothing, bare feet, and natural surroundings. It is a prehistoric origin myth, designed to install modern aesthetic values as eternal. (Feminists have long had cause to suspect caveman allegories, which never go terribly well for women.) The second, more subtle level of historicity consists of a medieval aspect to the couple’s heads, suggestive of the Arts and Crafts movement, with which Crane was aligned. The woman has long, well-ordered curls; the man, a pageboy-style bob; and both wear a circlet of beads on their heads. This late Victorian, precapitalist retro suggests at once a romanticization of this aesthetic figure and a reflexive awareness of its historical projection. Close on the heels of cinema’s invention, we see a projected image imagined not in the more familiar metaphoric terms of Plato’s cave, but as the origin of the art historical debate between line and color. And the concretization of woman as formless color in Crane’s image moves beyond the transhistorical patriarchy that underwrites this debate to propose, in addition, an ambiguous investment in the premodern within the modern—a desire for a species of modernist primitivism that will recur, along with gender, throughout this story.

Crane’s illustration figures the dialectic with which I began: line versus color is at once a long-standing debate in aesthetics and a historically specific question for early film theories. As Jacqueline Lichtenstein argues, a suspicion of the image has dogged Western art since Plato’s time, and the separation of disegno from colore enabled critics to shift from an unhelpful Platonic condemnation of painting to a more malleable Platonic schema in painting.4 Disegno (drawing) came to figure the masculine and meaningful aspect of reason in art, whereas color was relegated to the secondary role of providing emotion, pleasure, or raw material for the artist. The debate stretches back to antiquity but recurs at various points in the history of Western aesthetics. For example, Kant excluded color from the categories of the beautiful or the sublime, arguing that color might be charming, but it was inherently inferior to both of his central categories. Sir Joshua Reynolds contrasted the “simple, careful, pure, and correct style of Poussin” with the “florid” and “subordinate” style of Rubens. Although Rubens’s coloring is skillful, Reynolds finds it “too much of what we call tinted. . . . The richness of his composition, the luxuriant harmony and brilliancy of his colouring, so dazzle the eye, that whilst his works continue before us, we cannot help thinking that all his deficiencies are fully supplied.”5 Both Kant’s exclusion of color and Reynolds’s tinting and dazzle appear in film discourse, but most important for our current purposes is the nineteenth-century iteration of the debate, with neoclassicists advocating for line against colorists such as Delacroix.

We might not expect this debate to have a great direct impact on early film theory for the simple reason that the first decades of film were not shot in color. Certainly, many black-and-white films used tinting, toning, and other color processes so that audiences did see colors at the movies. Just as silent film was not actually silent, black-and-white film was not actually monochromatic. Iris Barry writes of the problems of using color in film, finding a lack of consideration of tone to be a failing of most color films and looking to the implicit colors seen in black-and-white reproductions of the Old Masters to explain the necessity of subtle shading in cinema.6 Reiterating Reynolds, she finds “tinted” color to run the risk of tastelessness. Critics of early cinema, then, could consider color as a factor in their experience of film. However, the importance of color to classical film theory is not limited to this possibility: both before and after the introduction of color stock, film critics drew on the debates on line versus color to shape their claims on cinematic value.

In his influential early account The Film, a Psychological Study, Hugo Münsterberg broadly opposes color in film, arguing that it detracts from the specificity of the new medium and ultimately reduces the film’s artistry. He addresses exactly the type of postproduction effect highlighted by Barry, allowing, “To be sure, many of the prettiest effects in color are even today produced by artificial stencil methods.”7 His compliment here is grudging, and he regards the pretty color effect as attractive but not aesthetically meaningful. We should note his use of the term pretty, which appears twice in this book, in both cases in contrast to a more valued aesthetic mode. In this instance, the pretty color effect is in contrast to black-and-white film, which Münsterberg finds to be superior: “We do not want to paint the cheeks of the Venus of Milo: neither do we want to see the coloring of Mary Pickford or Anita Stewart.”8 Just as in Lichtenstein’s account of aesthetics, color is supplemental to true art, and as Crane’s example suggests, the space of color is structurally understood as feminine, pretty, and passive.

Münsterberg’s engagement with the line / color hierarchy extends beyond his explicit critique of color film. In the “Emotions” section of his book, he condemns the excess of gesture and emotion in film in terms of light effects: “The quick marchlike rhythm of the drama of the reel favors this artificial overdoing, too. The rapid alteration of the scenes often seems to demand a jumping from one emotional climax to another, or rather the appearance of such extreme expressions where the content of the play hardly suggests such heights and depths of emotion. The soft lights are lost and the mental eye becomes adjusted to glaring flashes.”9 Here, the excess associated with melodrama (the gestural, the artificial, too much emotion) is imagined in terms of excessive visual effects (lights, glare, flashes) that suggest a dazzling of the spectator. This dazzle may not include color, but it is imbued with another aesthetic critique of color: the Greek notion of poikiloi. This term defines color as brightness or effect rather than as essence: “the dazzle that blinds the gaze, the sparkle that obscures vision.”10 For Plato, poikiloi implied sophistry, pretty words that hide the truth, and for Lichtenstein it is another variant of the seductive and dangerous feminine. In art historical terms, poikiloi implies a distinction between unadulterated color and false sparkle, and so, without referring to actual hues, Münsterberg draws on the aesthetic suspicion of the bright and gaudy.11

And it is not only Münsterberg who is suspicious of color. Classical film theorists with views as different as Béla Balázs and Rudolf Arnheim come together in their negative attitude to color film. We might compare their discussions of pictorialism, which Arnheim is broadly in favor of and Balázs entirely against. Despite this conflict, a strikingly similar reading of color emerges in each account. Arnheim, writing in 1935, advocates that film become more composed and painterly, but that it remain monochromatic. He argues that color films look “atrocious” because they remain too close to nature: “Nature is beautiful, but not in the same sense as art. Its color combinations are accidental and hence usually inharmonious. . . . We have become used to seeing a painting as a structure full of meanings; hence our helplessness, our intense shock on seeing the majority of color photographs.”12 Balázs takes an entirely different view on pictorialism, valuing film’s ability to move and rejecting anything too painterly. And yet his rejection of the pictorial (a more typical claim for classical film theory) is folded into a critique of color very similar to Arnheim’s: “One of the dangers of the color film is the temptation to compose the shots too much with a view to a static pictorial effect, like a painting, thus breaking up the flow of the film into a series of staccato jerks.”13

In these debates, color centers the larger problem of the cosmetic: meaningless in itself, color bespeaks a veiling or an even more anxiety-provoking lack of reason. David Batchelor has compellingly argued that the opposition to color charts a consistent prejudice in Western thought: “As with all prejudices, its manifest form, its loathing, masks a fear: a fear of contamination and corruption by something that is unknown or appears unknowable. This loathing of color, this fear of corruption through color, needs a name: chromophobia.” Batchelor links chromophobia to iconophobia, describing two modes of cultural rhetoric on color: “In the first, color is made out to be the property of some ‘foreign’ body—usually the feminine, the oriental, the primitive, the infantile, the vulgar, the queer or the pathological. In the second, color is relegated to the realm of the superficial, the supplementary, the inessential or the cosmetic. In one, color is regarded as alien and therefore dangerous; in the other, it is perceived merely as a secondary quality of experience, and thus unworthy of serious consideration. Color is dangerous or it is trivial, or it is both.”14 The aesthetic here is closely linked to ideas about gender, race, and sexuality, and in analyzing discourses such as color in film theory, we can grasp how power is imagined not only in representational politics, but in apparently apolitical questions of form and style. The pretty is not limited to the colorful, but color forms one of its major qualities. Classical film theory’s suspicion of color and arguments in favor of limiting its dangerous effects provide insight into cinema’s adoption of anti-pretty modes of thought.

As we see in Crane’s illustration, color is closely related to gender: the hierarchy of line and color attributes masculine reason to line and feminine emotion to color. Batchelor charts the origins of this hierarchy from Plato’s notion of cosmetics to patriarchal anxieties about feminine wiles. Therefore, “if color is a cosmetic, it is also—and again—coded as feminine. Color is a supplement, but...