![]()

1 E-Books and the Digital Future

AT EXACTLY 12:01 A.M. on March 14, 2000, Simon & Schuster began an experiment: the publisher released best-selling author Stephen King’s first digital electronic book, or e-book, the sixty-seven-page novella Riding the Bullet, on the Internet. By 11:59 p.m. on the fifteenth, an estimated half million people had downloaded King’s story, prompting Jack Romanos, Simon & Schuster’s president, to declare the experiment a resounding success: “We believe the e-book revolution will have an impact on the book industry as great as the paperback revolution of the 60’s.”1 Later that year, the soon-to-be notorious accounting firm of Arthur Anderson joined the celebration of e-books. In a dubious feat of actuarial prowess, Anderson’s consultants predicted that by 2005 no less than 10 percent of all books sold in the United States would be in electronic form.2 It appeared that the dusty old era of printed books was finally poised to give way to a sublime digital future.

Several years and a healthy dose of cynicism later, it seems clear that these heady claims about e-books were suffused with the same millennial hopes and dreams that had helped fuel the late 1990s dot-com boom and its accompanying faith in a resplendent technofuture. Despite the efforts of Stephen King, Simon & Schuster, and Arthur Andersen to locate themselves within the vanguard of an e-book revolution, the latter hasn’t quite reached the fevered pitch that book industry insiders had anticipated. The turning point seems to have occurred around 2001 when, in the words of Publishers Weekly, the book industry trade magazine, e-book denizens faced a “reality check.” Sluggish sales and the economic downturn following the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the United States led many hardware manufacturers and e-book publishers to divest themselves of their interest in e-books. Their doing so followed on the heels of Stephen King’s decision, in December 2000, to discontinue writing his second e-book, The Plant, after the number of those who had downloaded installments from his Web site without paying had grown too high by his estimation.3

Still, interest in and sales of e-books have rebounded of late. A 2003 report by the Open E-book Forum found that close to a million e-books had been sold in 2002, generating nearly $8 million in revenue; the first half of 2003 saw healthy, double-digit increases in units of sale over the preceding year. A second report, compiled by the Association of American Publishers, showed more modest gains of nearly $3 million in e-book sales among the top eight trade publishers. Of course, these reports don’t account for the innumerable e-books that people acquire for free from sites such as the University of Virginia Library’s EText Center (now the Scholars’ Lab). In 2001 alone the library recorded over three million e-book downloads of works that had passed into the public domain. Moreover, major academic textbook publishers such as McGraw-Hill and Thomson Learning continue to pursue e-books in earnest, with the former reporting per month revenue from e-publishing in 2002 in the hundreds of thousands of dollars.4

Two other higher-profile e-book ventures not only have helped to renew public interest in the technology but have also prompted some to begin imagining a world in which the content of books—perhaps of all books now in existence—would be little more than a click away. Since 2004, search engine giant Google has been busy digitizing part or all of the printed book collections of twenty-nine (and counting) major research libraries. The company’s self-described “moon shot,” also known as Book Search, promises to make content from millions of books freely available to those with Internet access, and perhaps one day even to realize the promise of a massively cross-referenced universal library accessible to all.5 On November 19, 2007, online retailer Amazon.com released Kindle, a portable electronic reading device whose express purpose, according to CEO Jeff Bezos, would be to bring books—“the last bastion of analog”—into the digital realm.6 Onboard mobile phone technology probably makes Kindle the first portable electronic reading device to provide for ubiquitous two-way communication between bookseller and consumer (available only in North America at the time of this writing). According to Bezos, “Our vision is that you should be able to read any book in any language that’s ever been printed, whether it’s in print or out of print, and you should be able to buy and get that book downloaded to your Kindle in less than 60 seconds.”7

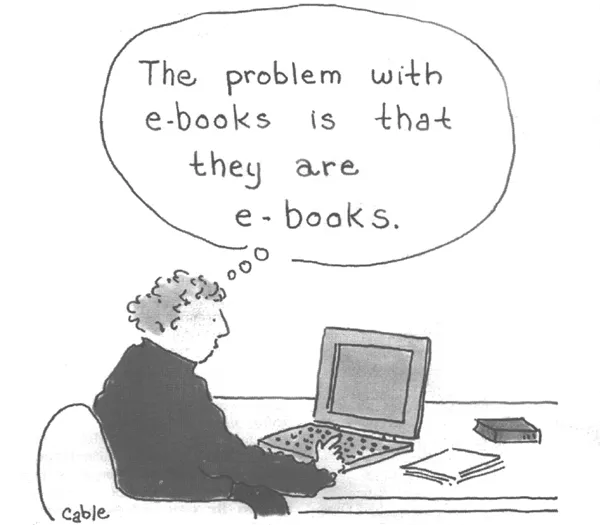

FIGURE 1 Printed books still seem to be the real thing.

SOURCE: CHRONICLE OF HIGHER EDUCATION, OCTOBER 31, 2005, B22. USED WITH PERMISSION OF CAROLE CABLE.

Despite all this think-big entrepreneurial optimism, many continue to doubt the worth of e-book technologies. Take a cartoon published in a 2005 edition of the Chronicle of Higher Education, whose caption reads: “The problem with e-books is that they are e-books” (fig. 1). If this tautological statement makes us laugh, we do so most likely because we share a highly specific, normative vision of books and book reading. This vision, which has been propounded for decades by journalists, literary humanists, educators, and academic theorists, places printed books and solitary, immersive acts of reading center stage in the bibliographic mise-en-scène. The joke works because for many people it’s intuitive to see e-books as crude copies of vaunted originals—that is, of printed books—and, in turn, to imagine the reading of electronic content as intellectually or experientially impoverished.8

Amusing though they may be, jokes like these are anything but innocent. They’re defensive assertions fueled by even more fundamental assumptions about the relationship between electronic and printed books. Just as “video killed the radio star,” many partisans of print believe that e-books threaten to kill off their paper-based counterparts. Their fears may not be altogether unfounded. Some book-scanning projects have resulted in the destruction and discarding of countless printed books because of the method by which the codex volumes are prepared for flatbed scanning, namely, the “guillotining” of their spines.9 (Google’s method is the exception here.) However, it’s not just the physical form of printed books that seems to be imperiled in the so-called digital age. Critics worry that their content could be jeopardized as well. The lack of standardization of e-books, combined with the penchant among hardware and software developers for “upgrading” file formats out of existence, would appear to render the digital existence of book content tenuous at best.10 E-books thus appear to some as harbingers of loss—of knowledge, authority, history, artistry, and meaning.

How could it be that e-books seem to offer equal parts promise and peril? It’s not enough simply to say they’re complex and contradictory cultural artifacts. Most—perhaps all—such objects are. What’s crucial to explore, rather, is the intricate web of social, economic, legal, technological, and philosophical determinations that collectively have produced them as such. The aim of this chapter is to map the conditions leading to the emergence of e-books in the late age of print and to investigate what’s at stake politically in current debates about their worth. Instead of trying to champion or condemn e-books, I’m more interested in considering their embeddedness within the broader history of consumer capitalism and property relations. Beyond their ability (or lack thereof) to store and retrieve information, what’s most intriguing to me about e-books is their capacity to manage it and, by extension, the actions of those who purchase or otherwise consume e-book content. I argue that e-books are an emergent technological form by which problems pertaining to the ownership and circulation of printed books are simultaneously posed and resolved.

The first section of this chapter represents a ground clearing of sorts. Because so much of the debate surrounding e-books has tended to hinge on the degree to which they reproduce the form and function of their printed counterparts, I want to spend some time sifting through this particular line of argument. My aim is to challenge the assumptions about originality, presence, and authenticity by which the debate gets framed so as to open up a different line of conversation about the history and social function of e-books. The next two sections explore some of the key conditions of emergence of e-books. I begin by investigating how, in the second quarter of the twentieth century, a host of cultural intermediaries promoted printed book ownership as a means to consolidate the budding consumer capitalism. Next I trace how concerns about the ownership, circulation, and reproduction of printed books helped fuel a fear that the latter had become troublesome with respect to expanding capitalist relations of production in the final quarter of the twentieth century. The final section explores how some contemporary e-book technologies embody and attempt to resolve this perceived problem, especially through the implementation of digital rights management schemes.

I suppose this chapter is about the disappearance of information, though not exactly in the sense the partisans of print would take it. Though I may share their concerns about the well-being of the historical record in the late age of print, ultimately that is of lesser importance to me. More significant is the growing power of holders of intellectual property (IP) rights to make information appear and disappear whenever they see fit—often for a fee.

A Book by Any Other Name

With characteristic fanfare for all things technologically sublime, in July 1998 Steve Silberman of Wired magazine reported on the impending release of “Book 2.0”—a host of new, portable e-book readers set to be unveiled in American consumer markets. In referring to this generation of e-books as such, Silberman framed the devices as the latest iteration of an extant technology. Their purpose, therefore, was not only to repeat but also to improve upon the most familiar qualities of printed books. A certain sense of loss nevertheless pervades his account of reading Kakuzo Okakura’s Book of Tea on a Rocket e-book. “I won’t be returning this Book of Tea to its little slipcase on my shelf,” he observed. “I miss the way the printed book’s type, with its tiny irregularities, is a Western equivalent of the wayward bristles that make a brush stroke more living than a line. But through the text—the bits—alone, Okakura’s mind speaks.”11

Silberman could read The Book of Tea on screen, but he seemed to do so despite, not because of, the intervening technology. Boredom loomed, and the traces of what he took to be Okakura’s presence are all that sustained his interest. Even they, purportedly, had been diminished, given how the e-book reader Silberman was using seemed to atomize the author’s soulful prose into innumerable electronic impulses and then to reassemble them into lifeless, uniform digital text. Silberman claimed that e-books fail because, although they repeat, they don’t repeat well enough. That is, they fail to duplicate the serendipitous flaws and minor variations that he believes imbue industrially manufactured printed books with warmth, difference, and depth—a personality akin to the aura Walter Benjamin said had declined because of mass reproduction.12

Essayist Sven Birkerts’s popular Gutenberg Elegies: The Fate of Reading in an Electronic Age offers a similarly dour account of the relationship between printed and digital text. Birkerts recognizes that screens and digits increasingly complement both written and printed artifacts in patterning communication and social interaction, facilitating the circulation of people and things and, more abstractly, conditioning our relations to space-time. He goes further, however, in questioning the larger social and epistemological consequences that allegedly flow from what he describes as the “triumph of the screen and the digital program”:13

Nearly weightless though it is, the word printed on a page is a thing. The configuration of impulses on a screen is not—it is a manifestation, an indeterminate entity both particle and wave, an ectoplasmic arrival and departure. The former occupies a position in space—on a page, in a book, and is verifiably there. The latter, once dematerialized, digitized back into storage, into memory, cannot be said to exist in quite the same way. It has potential, not actual, locus…. The same word, when it appears on the screen, must be received with a sense of its weightlessness—the weightlessness of its presentation. The same sign, but not the same.14

The electronic word may repeat its printed counterpart as pure sign, but the word’s transformation into abstract electronic impulses evidently leaves it listless, impalpable, diffuse—the same but different, deficient. Birkerts goes on to contend that this apparent dematerialization of the word results in the toppling of a whole tradition of textual authority. This coup d’état is epitomized by claims about the author’s death, an insistence on readers’ power, and a belief that writing occurs under conditions of erasure.15

Clearly Birkerts believes that our choices of reading and writing media are deeply consequential—even political—acts. Given his commitment to a quite traditional model of textual authority, it should come as no surprise that he eschews technologies that reduce the splendor of writing and reading to the vulgar processing of words. He writes: “I type these words on an IBM Selectric [typewriter] and feel positively antediluvian: My editors let me know that my quaint Luddite habits are gumming up the works, slowing things down for them.”16 Birkerts nevertheless delights in having opted to write with a typewriter rather than a computer. His editors’ frustrations confirm for him that his choice constitutes more than a mere preference for one technology over another. He sees his decision as an act of defiance against a hostile insurgency, a social order in which speed, ephemerality, and relativism apparently rule the day.

Yet it is precisely here—in the confidence Birkerts feels in slowly, methodically, t-y-p-i-n-g o-u-t w-o-r-d-s on his IBM Selectric—that his claims about presence, social power, and media begin to get all jammed up. Langdon Winner once famously quipped that “technology is license to forget.”17 Indeed, only a profound act of forgetting could sustain Birkerts’s claims about the transparency of typewriting. His typewriter, after all, is not only mechanical but electrical (hence, Selectric), and as such it’s a technology engaged in an abstract process of rendering. The mechanical energy Birkerts exerts in his keystrokes doesn’t directly result in the words he sees and reveres on the printed page. These words aren’t signs that would index his “hand” in any straightforward way. Rather, they result from the machine’s transduction of his keystrokes into electrical impulses, which then induce corresponding movements in the typewriter’s mechanism. Like it or not, an electrical charge infuses all of Birkerts’s writing, a charge produced by the very machine IBM touted in a 1962 advertising campaign as a device not for slowing you down but for making you “faster … more productive.”18

Perhaps, then, the electricity flowing through the machine’s intervening circuitry is the culprit. Would a purely mechanical typewriter more fully manifest Birkerts’s presence in, and thus his authority over, the words he produces? We cannot know for sure because an answer by anything other than inference would require us to detect and quantify traces of latent “spirit” energy—a pursuit more in keeping with the field of parapsychology.19 Nevertheless Martin Heidegger’s lectures between 1942 and 1943 on the philosopher Parmenides offer...