![]()

Queer Beauty

Winckelmann and Kant on the Vicissitudes of the Ideal

Uranists often ornament their apartments with pictures and statues representing good-looking youths. It appears that they love the statue of Apollo Belvedere in a manner all their own.

—Albert Moll, Perversions of the Sex Instinct

The Ideal is the manifestation of consciousness to itself, the pledge to the race of our existing in a process of development.

—John Addington Symonds, “Realism and Idealism”

§1. The history of modern and contemporary art provides many examples of the “queering” of cultural and social norms. It has been tempting to consider this process of subversion and transgression or “outlaw representation” (as Richard Meyer has called it), as well as related performances of “camp,” or otherwise gay-inflecting the dominant forms of representation, to be the most creative mode of queer cultural production.1 Whether or not this view is correct when applied to the history of later nineteenth-and twentieth-century art, we can identify a historical process in modern culture that has worked in the opposite direction—namely, the constitution of aesthetic ideals, cultural norms that claim validity within an entire society, that have been based on manifestly homoerotic prototypes and significance. There has been little subversion or camp in these configurations. Indeed, perhaps there has been a surfeit of idealizing configuration and normalizing representation. But as Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s art history and Immanuel Kant’s aesthetics might suggest, such idealization can be no less queer than camp inflections or outlaw representations.

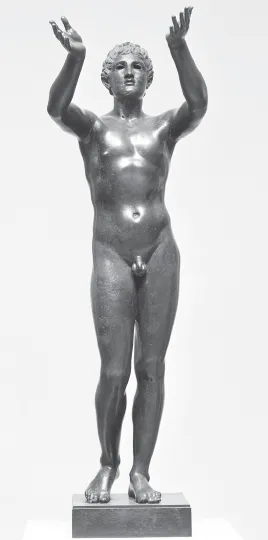

§2. In this respect we might consider modern European replications of the Classical Greek pederastic imagery of ephebic male beauty. At Sanssoucci at Potsdam, his pleasure palace outside Berlin, Frederick II of Prussia erected the so-called Adorante or Betende Knabe (Adoring Youth), acquired in 1747 and now understood to be an original bronze of the early Hellenistic period, at the end of a garden walkway that he could survey when seated in his private library (figure 2). There Winckelmann saw it in 1752. The king was the only person who officially had access to this privileged view. But outside the building, visitors could readily see how the sculpture related to the king’s quarters. Christoph Vogtherr has noted that observers could remark its association with the king’s tomb, which stood nearby readied for his eventual occupancy. Vogtherr has proposed that Frederick’s art collections at Sansoucci tried “to make a synthesis between the norms of society and love,” that is, Frederick’s loves for men, especially Hans Hermann von Katte, special friend of the crown prince before his accession, executed for sodomy by Frederick’s father (then the king) in 1730.2 “Synthesis between the norms of society and love”: Vogtherr applies this phrase to Frederick’s gallery of paintings by Antoine Watteau and other contemporary artists. It could equally apply to Frederick’s collection of antiquities, specifically his installation of the Adorante.

But what exactly was this synthesis? Regardless of the personal connotations of the sculpture for Frederick, the Adorante (formerly owned by such collectors as King Charles I in London and the counts of Liechtenstein in Vienna) shows that pederastically determined imagery can achieve normative status—Vogtherr’s synthesis of personal erotic love and social norms. Displayed by leaders of church and state in prominent public places, the imagery has signified and legitimated dynastic, national, and imperial aspirations. At Sanssoucci the Adorante certainly displayed the king’s taste and learning. In figuring the eroticized (and infantilized) position of the worshipful young body politic in relation to the king’s real person, it embodied Frederick’s paternalistic (and incorporative) claims as king of Prussia—claims that had initially been threatened by the taint of homosexuality affixed to him in his youth.

FIGURE 2. The Adorante (“Adoring Youth”), c. 300 BC. Bronze, ht. 128 cm. Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin. Photo Albert Hirmer. Courtesy Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz/Art Resource, New York.

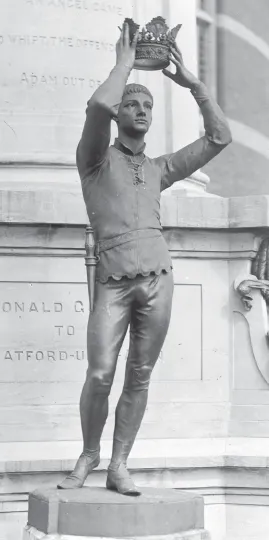

We can pursue this particular image in later replications. In the 1880s, for example, the British sculptor Ronald Sutherland Leveson-Gower, a relative of Queen Victoria and an heir to the vast holdings of the dukes of Sutherland, recalled it in his figure of Prince Hal (later King Henry V) on the forward face of the Shakespeare Memorial at Stratford-upon-Avon, dedicated in 1888, one of England’s few monuments to its greatest writer (figure 3). On the Shakespeare Memorial, Hal served as the “Allegory of History.” Gower used the Adorante, likely studied by him in a visit to Potsdam, to set the pose of his nude model, a young male studio hand. Gower went so far as to consider that he might show Prince Hal in the nude too, though Shakespeare’s text gave no support for the idea. In Henry the Fourth, Part 2, Prince Hal takes the crown from his dying father’s bedside in Westminster Abbey and reveals himself to be “Harry of England,” soon to be victor at Agincourt—one of the very types, as the poet Algernon Charles Swinburne noted in 1880, of the “militant Englishmen” who founded the British Empire in India, Africa, and elsewhere. Nude or not, but imperial and glamorous, Gower’s Hal presents a package with familiar pederastic and homoerotic associations. In addition to dramatizing Hal’s bulging crotch and clenched muscular buttocks (figures 4, 5), Gower paired the prince with Falstaff, the fat old knight who regarded the prince, the Achilles to his Centaur, as a fellow “minion of the moon” (that is, a nighttime follower of Diana and Bacchus) and Falstaff ’s “sweet wag,” his “most comparative, rascalliest, sweet young prince.”3

FIGURE 3. Ronald Sutherland Leveson-Gower (1845– 1916), Prince Hal: The Allegory of History. Lifesize bronze; detail of the Shakespeare Memorial, Stratford-upon-Avon, unveiled 1888. Photograph of original grouping (1888–1936) by Catherine Weed Ward (1851–1913), 1935. Courtesy George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film, Rochester, New York.

It is debatable whether these replications gained prestige and power because of their association with Greco-Roman and Elizabethan pederasty or despite it. But undeniably they were fully intelligible to many modern observers in pederastic terms. In 1808 a distinguished antiquarian, Conrad von Levezow, produced the first scholarly treatise on the ancient imagery of Antinous, the slave, lover, and companion of the Roman emperor Hadrian. In the same year, Levezow noted commonly accepted identifications of the Adorante as an Antinous or (even better) a Ganymede, cupbearer and bedfellow of Zeus. (In fact, a special type of Antinous-Ganymede, as it were a superpederastic image, had been identified by another scholar in another sculpture that Levezow had not seen.) One or the other of these identifications had probably been accepted by Frederick, who also displayed an Antinous in the type of “benevolent Genius” in his garden.4 On the basis of his comparative knowledge, Levezow felt that the facial features of the Adorante did not quite match those of an Antinous. The other features were a different matter. Levezow believed that ancient arists usually avoided the reputedly feminine appearance of Antinous, for it identified him as the emperor’s catamite; they preferred to depict him to have an ideally male character—athletic or even Apollonian. In Frederick’s statue, however, the ephebic grace of the figure was undeniable. In the end, Levezow left the iconography indefinite; at best, he chose to affiliate the statue with an obscure class of adoring figures, both male and female, that had a Classical Greek vintage. According to Levezow, the Adorante might be attributed to the sculptor Euphranor, who worked in the “beautiful style” identified by Winckelmann (i.e., fourth century BC). As such it might be associated with some of the entries in the long series of male statues of victorious athletes that had been arrayed at Olympia in Elis in the fifth and fourth centuries BC and later—historical horizons to which I will return.

FIGURE 4. Detail of Prince Hal, Shakespeare Memorial, Stratford-upon-Avon (new grouping, 1936 to the present). Photograph by the author, 2001.

FIGURE 5. Detail of Prince Hal, Shakespeare Memorial, Stratford-upon-Avon (new grouping, 1936 to the present). Photograph by the author, 2001.

Despite these broadly homoerotic and specifically pederastic connotations, all the works in question could be admired as expressions of the highest ideals of truth, history, and beauty. If Gower literally dressed up his principal artistic source (as well as his real human model) for Prince Hal, Levezow’s review of interpretations of the somewhat risqué iconography of the Adorante (he did not hesitate to mention the Knabenliebe, or love of boys, attributed to Zeus and Hadrian and implicitly to Frederick) did not prevent its reproduction in plaster casts and other media throughout the nineteenth century.5 As I have already suggested in §1, such replications (whether Frederick’s or Gower’s or the cast industry’s) proffered what might be called queer beauty. I use the term beauty in its specifically Kantian sense to denote a normative communalization of judgments of taste that claims deep aesthetic agreement, gains wide social assent, and relays an entire community’s ideals of itself for itself. Figuratively the Adorante at Sanssouci is the Prussian people—Frederick’s lover. And Gower’s Prince Hal is England incarnate.

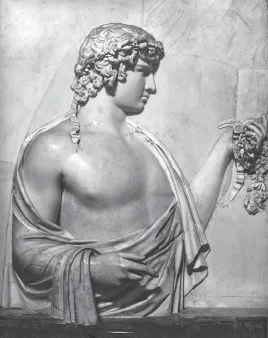

Now seemingly there should not be any queer beauty in this Kantian sense. That is, there should not be any queer beauty or queer beauty. But clearly there was. In the late 1750s at his villa in Rome, Cardinal Alessandro Albani installed a striking relief of Antinous, found at Hadrian’s villa at Tivoli in 1737, in a public salon (figure 6). According to Winckelmann, Albani’s art adviser at the time, the relief from Tivoli did not quite reproduce the “high style” of beauty in Classical Greek sculpture of the fifth century BC, identified above all with the sculptor Phidias. The voluptuousness of Antinous in Hadrian’s relief departed from (or alternately it had yet to be fully idealized in) the tranquillity of the most elevated works of Greek style. Needless to say, the relief had not been made by a Classical Greek artist in the first place: though perhaps made by an ethnic Greek sculptor, it had a specifically Hadrianic vintage.

FIGURE 6. Antinous. Marble relief, c. AD 130; discovered at Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli in 1737 and installed at the Villa Albani, Rome, by 1760. Museo di Villa Albani, Rome. Courtesy Alinari/Art Resource, New York.

Following in the footsteps of the Roman emperor, Winckelmann probably appreciated the relief of Antinous from Tivoli in the same way that he fetishized the marble head of a faun that he installed in his apartment in the Villa Albani, his “Ganymede,” as he called it, “whom I would kiss before the eyes of all the saints.”6 As in the case of Frederick’s Adorante, however, and given Albani’s highly visible ecclesiastical position, the cardinal’s installation of the relief from Tivoli did not have to imply that he adored it pederastically. Perhaps he did; historians have amassed circumstantial evidence for a homoerotic social network headquartered at the Villa Albani. But if this social network was a distinctive subculture, as some historians have concluded, it was equally Kultur. The relief from Tivoli belonged to a complex sediment of many kinds of ancient and modern beauties displayed at the Villa Albani—beauties that could be the objects of antiquarian devotion or aesthetic Kult. Regardless, Albani’s installation of the relief certainly showed that he judged it to be beautiful. And so did many other viewers, whether homoerotically interested or not. Edward Gibbon, who condemned sodomy, found it “admirably soft, well turned and full of flesh.”7 In Pompeio Batoni’s portrait of an unknown patron, perhaps one of the wealthy British, German, or Scandinavian gentlemen who were guided around Rome by Winckelmann, the young Grand Tourist (painted circa 1760–65) was not simply affiliating himself with Greco-Roman pederasty when he displayed—and gestured at—the relief of Antinous from Tivoli placed on the table beside him (figure 7).8 He did not have to position himself as a Hadrian to this Antinous. Rather, he positioned himself as a Winckelmann or an Albani to this Antinous: he displayed his correct contemporary taste for Classical beauty, originally homoerotic in its sexual aesthetics, as a newly canonical cultural norm. This norm had emerged in a historical process, the synthesis identified by Vogtherr at Sansoucci, that had moved in the duration of one generation or less from Winckelmann’s eroticized and even “homosexual” enthusiasm to Albani’s catholic cultivated approbation and finally to Batoni’s recognition of a virtually universal standard, a cultural beacon, that had recently been established among a pan-European class of elite young men. To explore this process, we must start, as suggested in the introduction, with Winckelmann’s eroticized enthusiasm for ancient art.

FIGURE 7. Pompeio Girolamo Batoni (1708–87), Portrait of a Young Man, c. 1760–65. Oil on canvas, 97 1/8 × 69 1/4 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Rogers Fund, 1903 (03.37.1). Image copyright the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

§3. Despite his veneration for Socrates, Winckelmann (as Bernard Bosanquet and Benedetto Croce realized) was an anti-Platonic Platonist. (I have briefly reviewed Bosanquet and Croce’s interpretations of Winckelmann in the introduction.) Like Socrates and Plato, Winckelmann believed that erotic desire promotes human knowledge of—and participation in—the ideal; eros is the ladder of the ideal. But, unlike the mature Plato, and perhaps more like Socrates in Xenophon’s sympathetic and worldly portrayal of him, Winckelmann did not really believe that the artistic realization of an ideal involves transcendence of erotic desire, its wholesale conversion into a love of the good, the just, and the beautiful, as the strict-constructionist Platonist tended to suppose.9 (This Platonist was a figure as much imagined by Winckelmann and his contemporaries as actually to be found in the ancient academy or the modern schools. But this problem need not detain us here; every generation has produced the Plato and the Platonism that it thinks it needs.) Instead, eros is always required, even in the ideal or as the ideal. Indeed, Winckelmann could not take the ideal to be the endpoint of human knowing, that is, the endpoint of erotic desire. As his art-historical writings implied, Winckelmann imagined—and here is the distinctively anti-Platonic note—that there is something to be sensed beyond the ideal and as it were by way of the ideal and even if it is difficult to realize this horizon or to represent this condition in the ideal: namely, the continuous movements of desire toward ideality, in ideality, and around ideality. It is these movements that constitute the primal conditions of knowing in a human being.

To be specific, Winckelmann’s history of the process of aesthetic idealization offered a reconstruction of the creation and display of sculptures in the ancient palaestra or wrestling grounds, especially at the pan-Hellenic gaming grounds at Olympia. (In his meditations on Greek civilization in the Phenomenology of Spirit and the Lectures on Aesthetics, G. W. F. Hegel relocated the history in question at these sites to the Greek temple, which was surrounded by sculptural dedications, and the Greek theater, in which human actors performed as if in the form of sculptures; Winckelmann’s history of art and the politics and erotics that it marked never fully recovered from these tendentious deflections.) In the absence of scientific excavation of these sites, Winckelmann’s reconstruction was largely speculative; it was based primarily on Pausanias’s description of Greece and other texts. Indeed, in the History of the Art of Antiquity Winckelmann’s description of the display of sculptures at Olympia took the form of a report of what he explicitly called a dream, an imaginative or hallucinatory visualization of its original aspect.

According to Winckelmann, the sculptural displays of victorious athletes erected in the palaestra inspired young men to physical and moral achievement. In turn, the beautiful bodies of athletes who had cultivated these artistic ideals were used as mater...