1

Diaspora

Struggles and Connections

People of sub-Saharan Africa have migrated, in wave after wave, to other regions of the world. The initial movements—beginning seventy thousand years ago—involved settlement of the Old World tropics; this was followed by occupation of Eurasia, Oceania, and the Americas. In the last few millennia, as societies and civilizations grew up throughout the world, Africans have continued to migrate and settle overseas. For the black people of sub-Saharan Africa, this “sunburst” of settlement beyond their homeland has brought particularly close linkages to Egypt, other parts of North Africa, and Arabia. Further settlements across the waters of the Indian Ocean, the Mediterranean Sea, and the Atlantic Ocean brought African settlers to Asia, Europe, and the Americas. It is a sad reality that, from the fifteenth through the nineteenth centuries, most African migrants beyond the continent were forced to travel and to serve as slaves. But in slavery and in freedom, African migrants and their descendants made their mark. Culture and commerce have flowed steadily and ties of personal attachment have been established and maintained among the regions of Africa and the African diaspora. In the twenty-first century, those earlier migrations and cultural interactions of people of African descent retain as much significance as ever.

This volume narrates the last six centuries of connections among black people in Africa and throughout overseas regions and provides some background on earlier times. It is a complex tale of cultural development, enslavement, colonization, struggles for liberation, and construction of modern society and identity. At the same time, this work poses and attempts to address some of the important questions that still face us as a result of the African diaspora. The analytical framework that shapes the chronological narrative presented here relies on five central themes: diaspora and its connections, the discourse on race, economic transformations, family life, and cultural production.

Diaspora

The analysis of diasporas—the migrations that brought them about and the dynamics of these dispersed communities—has become a significant topic in the work of historians, sociologists, and other scholars.1 Social scientists today use the term “diaspora” to refer to migrants who settle in distant lands and produce new generations, all the while maintaining ties of affection with and making occasional visits to each other and their homeland. The diaspora of Africans takes its place alongside the diasporas of Chinese, South Asians, Jews, Armenians, Irish, and many other ethnic or regional groupings. Diasporas can be large or small: the Jamaican diaspora lies within the African diaspora; the Palestinian diaspora within the larger Arab diaspora. They are new and old. More than two thousand years ago, for example, a Polynesian diaspora launched the settlement of many central Pacific islands.

“Diaspora” is an ancient term, long used almost exclusively in reference to the dispersion of Jewish people around the world. An interesting history of the term comes out of the diffusion of Jewish and Greek populations in the ancient world. From the time of the Babylonian captivity, Jews had been divided between their Palestinian homeland and Babylonia, and after they were freed from enslavement in Babylon they spread from Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean shores. Jewish populations held onto their religion, but they tended to embrace the local language. For instance, many adopted Greek, and thus it was that the Greek-speaking Jews of Alexandria, the great commercial city of the Egyptian coast, decided in roughly 200 BCE to support a translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek. This translation, the Septuagint, used the Greek term “diaspora” (from the sowing or dispersal of seeds) to translate several Hebrew terms that described the scattering of Jews outside the Jewish homeland. As Jews continued to scatter voluntarily and involuntarily through Europe, North Africa, and Asia, the term “diaspora” moved with them. With the rise of Christianity, the Septuagint and the term “diaspora” entered the Greek and Latin versions of the Christian Bible.

How did the term “diaspora” begin to be applied to the experience of Africans? According to two of the founders of African diaspora studies, George Shepperson and Joseph E. Harris, the term was used and perhaps coined at the time of an international conference on African history held at the University of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania in 1965.2 In an era when African and Caribbean countries were gaining independence and when movements for civil rights in those nations and the United States brought black people to the political forefront and into increased contact with one another, a renewed interest grew in tracing the historical contacts among Africans and people of African descent outside the continent. This was also a time—two decades after World War II and the subsequent creation of the state of Israel—when analyses of the Holocaust and of Jewish history brought attention to the Jewish diaspora and comparisons with other migrations. Expanding studies in African history and culture, including the importance of slavery in the history of Africans abroad, produced an interest in the Jewish diaspora analogy. Step by step, there developed scholarly studies of the African diaspora, university courses on the subject in Africa and in the Americas, and a growing public consciousness of diaspora-wide connections.3 Continuing struggles for the independence and civil rights of black people (in South Africa, Zimbabwe, and the Portuguese-held territories of Angola, Mozambique, and Guiné-Bissau) encouraged and expanded transatlantic solidarity. One form of such solidarity was the large-scale involvement of Cuban troops in support of the MPLA government of Angola after 1975; another was the campaign for boycotting South African businesses led by Trans-Africa, the U.S.-based black lobby.

At a cultural level, diaspora-wide connections developed in the widespread adoption of Ghanaian Kente cloth, hair styles involving weaving and braiding, and the sharing of musical traditions from Africa, North America, the Caribbean, and South America. By the 1990s, consciousness of the African diaspora had become wide enough that the term “African diaspora” began to be used much more extensively, in academic circles and in black communities. As with other aspects of African diaspora history, adoption of the term “diaspora” took place not only in English, but in Spanish, Portuguese, French, and other languages. Then, once the term “diaspora” gained currency in the study of Africans abroad, scholars began applying it to Chinese and other migrant populations.4

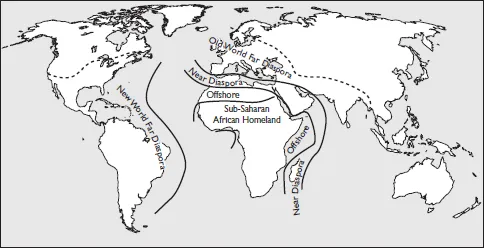

I have chosen to organize the geographical framework of this study into three great areas, which I label as the African homeland, the Old World diaspora, and the Atlantic diaspora (see map 1.1). By “African homeland,” I mean sub-Saharan Africa, the homeland from which black peoples have voyaged in freedom and slavery. By “Old World diaspora,” I mean all the regions of the Eastern Hemisphere in which sub-Saharan Africans have settled: North Africa, western and southwestern Asia, Europe, South Asia, and the islands of the Indian Ocean. By “Atlantic diaspora,” I mean the Americas and also the islands of the Atlantic and the mainland of western Europe. Each of these three regions has its own history, but these histories are tightly connected. For instance, Africans first came to Europe as part of the Old World diaspora, but as the Atlantic slave trade grew, Africans came to Europe especially by way of the Atlantic.

MAP 1.1 Regions of the African Diaspora

In my opinion, something is gained in this history by giving attention at once to the African continent and to all the regions of black settlement outside the continent. So I propose a formal framework for studying the world of black people in this way: I call it Africa-diaspora studies.5 This is an approach that traces connections among the various regions of the black world and emphasizes the social dynamics of those connections. In general, the sunburst of African settlement in the diaspora continues to interact with the continent’s bright orb. More precisely, this perspective on the history of the African diaspora explores four overlapping types of connections in the history of black people: (1) interactions among black communities at home and abroad, (2) relations with hegemonic powers, (3) relations with non-African communities, and (4) the mixing of black and other communities. These four dynamic dimensions of Africa-diaspora studies, explored across the regions of the black world, add up to a comprehensive yet flexible concept for analyzing the broad historical experience of black people and for setting that experience in a broader social context.

Interactions Within the World of Black People

This initial dimension of analysis addresses the migrations from Africa to the Americas and elsewhere, the survival and development of African culture in the diaspora, cases of return migration to Africa, and the many instances of development and sharing of political and cultural traditions among black peoples. More broadly, this is the study of interplay among Africa, the Atlantic diaspora, and the Old World diaspora. These demographic and cultural connections among black peoples form the core of the history we will trace.

Relations of Black People with Hegemonic Powers

These hegemonic powers, imposing their wills on black people, included slave masters, imperial conquerors, colonial or national societies dominated by propertied elites, government-backed missionaries, and dominant national cultures of the twentieth century. The propertied classes—in the diasporas of the Atlantic and the Old World and, later, in Africa—not only dominated their slaves but mixed socially and sexually with them. For people in slavery, a great deal of their existence was conditioned by the masters who restricted and oppressed them, changing their lives relentlessly. Similarly, people in the African colonies of the twentieth century found their lives pressured and transformed by the colonial powers in general and by individual Europeans. This dynamic brought suffering, resistance, debate, accommodation, and imaginative innovation in response. Resistance to these powers has occupied much of the energies of black people.

Relations of Blacks with Other Nonhegemonic Racial Groups

In the Old World, blacks interacted with people of Arab, Iranian, Turkish, and Indian birth, and with those brought as slaves from the Black Sea region. In the Americas, black communities interacted with Amerindian communities. Later on, black people in the Americas and in Africa interacted with immigrants from India, China, and the Arab world. And in a steadily growing number of instances, black people interacted with white communities under conditions where neither group was a master class—in Europe, for instance. These community interactions engendered new ethnic groups, caused competition for land and for ways to make a living, created political rivalries, and encouraged cultural borrowing and occasional alliances.

Mixing—Biological and Cultural—of Blacks with Other Populations in Every Region of Africa and the Diaspora

These mixes in population and culture are sometimes counted as part of the African tradition: in the United States, for example, mixes of black and white commonly become part of the black community. Sometimes the mix is treated as a category unto itself: the notion of “mestizo,” common in Latin America, is often treated as a social order distinct from its white, black, or Amerindian ancestry. And sometimes the mixes leave the black community and join the hegemonic white community, as in the case of the “passing” that has taken place throughout the African diaspora. In the Old World diaspora, including sometimes in Europe, the progeny of blacks and others tended to be treated as part of the dominant community. “Mixes,” it should be remembered, can be of several sorts: residential mixing, family formation across racial lines (voluntarily and involuntarily), and eclectic sharing of cuisine, dress, music, and family practices.

The point of this history of the African diaspora is to sustain a story of all four dimensions: the lives of black communities at home and abroad, their relations with hegemonic powers (both under the hierarchy of slavery and in the unequal circumstances of postemancipation society), their relations with communities of other racial designations, and the various types of mixing of black and other communities. The narrative shifts among these issues and pauses occasionally for an analysis of each era’s major interpretive questions. Through narratives of social situations but also through cultural representations of life’s crises and disasters, this volume balances the differences and the linkages among these four dimensions of the unfolding narrative of the African diaspora. The African continent appears not only as ancestral homeland but as a region developing and participating in global processes at every stage. The exploitive actions of slave masters and corporate hierarchies appear as a major force in history, but so do the linkages among black communities. The tale of an embattled but highly accomplished African-American community in the United States unfolds throughout the narrative, but so do the experiences of black communities in Brazil, Britain, and India. The African heritage shows itself not only able to retain old traditions but also to innovate and incorporate new practices through mixing, intermarriage, and cultural exchange of blacks with whites, Native Americans, Arabs, and South Asians.

My interpretation, organized around these four priorities, differs from other well-known interpretations of the African diaspora and its past. The difference comes partly because of interpretive disagreements I have with other authors, but mostly because this book is set at a wider scale than previous works. One such major interpretation is A frocentricity, by Molefi Kete Asante. His work, which gained wide attention with its second, expanded edition in 1988, linked today’s African-American population to its African heritage.6 Dr. Asante put forth “Afrocentricity” as a philosophy and program for social change, and he connected it in particular to traditions of ancient Egypt and to West African traditions of the nineteenth century. His interpretation did not say much about slavery and emancipation in Africa and overseas, and it made only brief reference to the African diaspora in Europe, Latin America, or the Indian Ocean. The Afrocentricity approach focused on building pride in African-American communities but stopped short of analyzing interaction and transformation. Asante’s emphasis was therefore more on race than on community, more on heritage than on exchange, and more on unity than on variety.

Another major interpretation focuses on “the Black Atlantic,” a term that developed in the 1990s to describe widespread connections among black people. This phrase, popularized by the black British sociologist Paul Gilroy in his 1993 book of the same name, gained wide attention as a descriptor of literary culture.7 The difference is one of emphasis, but it is an important difference. The “African diaspora” refers initially to the world of black people. The Black Atlantic, in contrast, focuses primarily on the interaction of black people and white people in the North Atlantic. It emphasizes blacks as a minority and often a subject population in an Atlantic world dominated by Europeans. Within that framework, it argues that black people created a “counterculture of modernity,” a set of cultural contributions that expressed their particular response to the challenges of modernity and had a substantial creative effect on “Western culture” as a whole. From a time perspective, analysis within the Black Atlantic focus is restricted to postemancipation society, while the African-diaspora focus employed here includes not only the times since emancipation but also the previous era of Atlantic slavery, and even the times before the large-scale enslavement of Africans. The perspectives of Black Atlantic and African diaspora thus overlap substantially, but they also retain distinctions so significant that they should not be confused with ea...