![]()

A SOUTH STREET STORY

Barbara G. Mensch

![]()

![]()

“WHAT’S A NICE GIRL LIKE YOU DOIN’ IN A PLACE LIKE THIS?”

![]()

DURING THE SUMMER OF 1979 I was looking for a new place to live. I noticed an ad listing a loft for rent in the South Street area of Lower Manhattan. For three weeks, I dialed the phone number frequently but had no luck in reaching anyone. On what I’d decided would be my very last attempt, someone finally answered. He agreed to show me the space the next day.

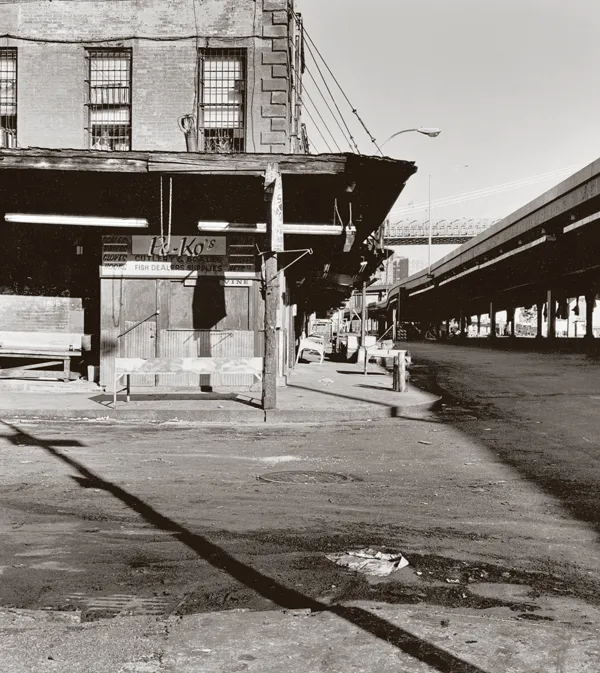

It was intriguing to walk past the Brooklyn Bridge looking for the street address. I knew that since the days of Melville and Whitman, this waterfront had been a vital maritime center bustling with trade and commercial activity. Now, the heritage of the area was reflected in its rude, decaying storefronts, potted cobblestone streets, and weirdly tilted commercial lofts. With the exception of a small group of artists living in the run-down warehouses, the waterfront was largely unpopulated.

I located the ancient brick building and rang a makeshift door buzzer, its wires haphazardly dangling down the side of the building. After a short while, a wiry young man greeted me at the front door. I followed him up five flights to the top of the shaky stairwell, and he opened the door to a loft illuminated only by a single light bulb hanging from the ceiling. As my eyes adjusted, it was possible to discern large black circular imprints on the wooden floor, suggesting that at some time in the building’s past, rows of barrels had stood there. The brick-walled room was musty and damp.

There was also a set of broken stairs leading to the roof. Curious, I climbed up and unlatched the door. Outside, the view of the Brooklyn Bridge was astonishing. The towers of the bridge, bathed in the late afternoon light, were breathtakingly beautiful. From another vantage point I could see the East River, the abandoned docks under the bridge, and the sheds of the Fulton Fish Market. An old man with a hunchback was busy feeding pigeons in a makeshift wire coop on the adjoining rooftop. With a broad smile showing his corroding dentures, he waved in my direction. Standing on the roof, I felt inspired by the bridge, and at peace being in such an out of the way, off the beaten path place. I knew in an instant that this was my new home.

My first friend in the neighborhood was a former sailor from England turned ship restorer and carpenter. He lived around the corner, in a decrepit three-story brick dwelling with a sloping roof. My neighbor had a great interest in the maritime history of the area, and insisted that the origins (foundation) of his building could be traced to the Dutch settlers. Once in a while he would spin romantic tales of the nineteenth century, recounting stories about the waterfront when it was filled with hotels, dance halls, brothels, and saloons, where gamblers instigated fights between dogs and rats.

My friend walked with a limp and had a thick British accent. When we took walks around the neighborhood, he would often carry a copy of Herbert Asbury’s book Gangs of New York and would read aloud:

A famous Water Street resort was the Hole-in-the-Wall, at the corner of Dover Street, run by one-armed Charley Monnell and his trusted lieutenants, Gallus Mag and Kate Flannery. Gallus Mag was one of the most notorious characters … a giant Englishwoman well over six feet tall so called because she kept her skirt up with suspenders or galluses. She was bouncer of the Hole-in-the-Wall and stalked fiercely about the dive with a pistol stuck in her belt and a huge bludgeon strapped to her wrist. It was her custom after she had felled an obstreperous customer with her club to clutch his ear between her teeth and so drag him to the door, amid the frenzied cheers of the onlookers. If her victim protested or struggled she bit his ear off … she carefully deposited the detached member in a jar of alcohol behind the bar in which she kept her trophies in pickle…. She was one of the most feared denizens of the waterfront.

The dive was finally closed after seven murders had been committed there in a period of less than two months.

When we sat by the piers, there were rare moments when the wind blew the smell of salt water off the river. Then, it was easy to imagine South Street when it was known as “The Street of the Tall Sailing Ships.” My friend would spin maritime tales like “The Mystery of the Mary Celeste,” the ship that set sail from South Street in November 1872 for the Azores and soon afterward was found drifting in the Atlantic with no one on board.

As a young photographer, I would wander the neighborhood, exploring and photographing simple “events.” At the time, I was fascinated by the art of Walker Evans and Berenice Abbott, whose approach to image making was powerfully direct. That seemed appropriate for capturing the area’s hidden beauty.

A few steps down from where I lived was a rag shop. Once a month, the proprietor would place a Dumpster on the street filled to the brim with cast-off inventory. People would climb in to look for pieces of fabric, articles of clothing, or a pair of matching shoes to wear.

The ancient buildings that lined the streets all had crumbling brick façades, windows that were mysteriously boarded up, and weather-beaten hand-lettered signs announcing such businesses as MON ARK SHRIMP, SEACOAST FISH, and VARIETY FISH. In the daylight hours, the doors were closed and there was never anyone around.

My intriguingly “undiscovered” neighborhood was about to undergo monumental change. Beginning in the 1970s, the press reported plans to demolish the piers of the fish market and restore the surrounding Schermerhorn Row, one of the oldest streets in downtown Manhattan. A new, expansive shopping mall complex filled with chain clothing stores, novelty merchandise shops, souvenir vendors, and fast-food eateries would be built in their place. I read in the New York Daily News that “The City planners are talking about glass and spindled steel and a quaint replica of New York’s long ago harbor that will rise up like Disneyland out of the ashes of the market.” Inevitably this would cause problems for the Fulton Fish Market. There was talk of moving the market to Hunts Point in the Bronx.

The spokesman for Local 359 of the United Seafood Workers of the Fulton Fish Market, Carmine Romano, was quoted: “We’ve offered to match them with 10 million dollars of our own money to renovate and improve the market as it is right here, but they don’t want to talk about it. If they move us, they’re going to put 200 of my men out of work and put a lot of the smaller wholesalers [fishmongers] out of business.”

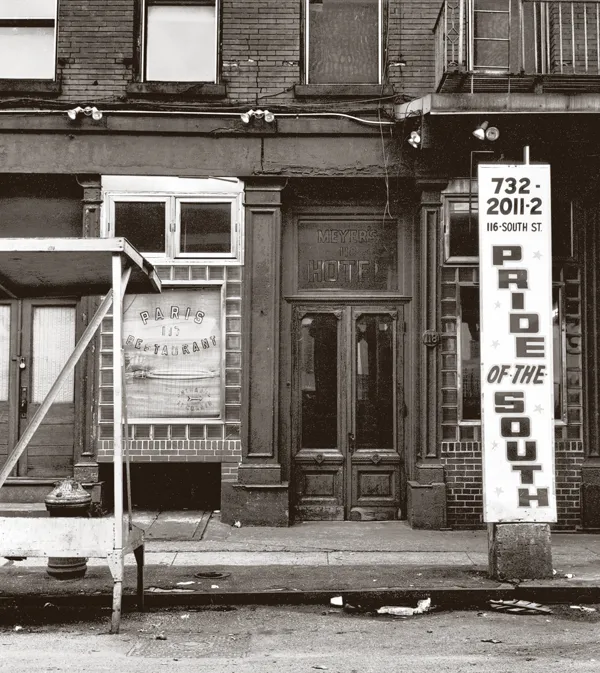

A neighbor mentioned that Meyer’s Hotel and the bar located on the ground floor of the building had recently been sold. The hotel, on the corner of South Street and Peck Slip, had been open since 1873. The bar, called the Paris, served food and drink to the waterfront crowd and was open all night.

Meyer’s Hotel had a noble history. For years, it accommodated the bay men who worked the fishing boats (smacks and trawlers), the draggermen (fishermen who specialized in catching shellfish), the lumpers (men who unloaded the fishing boats), the longshoremen who unloaded the tramp freighters (ships that traveled around the world picking up and delivering different cargoes—“tramp” was a reference to a “female tramp,” or prostitute), sailors coming to port, and the men who worked the “double headers” (unloading the boats during the day and then working in the fish market at night).

During and after World War II, the hotel served as a place of refuge for sailors in the merchant marine, veterans who had fought the Germans in the Atlantic. Recently, a friend who grew up in the area recounted: “It was an old man’s hotel, subsidized by the government. There were guys walkin’ around with no legs, or their arms missin’, blown to bits when their ships were torpedoed…. They were all remarkable men and they served their country with honor.”

One day, as I stood watching the workmen emptying the top floor of debris, I met the new owner. “What are you going to do with the building?” I asked. He appeared to be uncomfortable with my question. He remarked that he was eager to convert the hotel into residential apartments, and the Paris into a daytime bar. “I want to make a beautiful place to attract the intellectuals,” he responded, then walked away.

The past, the sense of the area’s long history that so intrigued me, was slipping away. I wanted to photograph the workers from the time-honored Fulton Fish Market who still congregated late at night in the old Paris. They remained in the last of the waterfront jobs.

It was the middle of winter, about 4 a.m., when I first went down to the Paris Bar. Nothing could have prepared me for what I saw as I pushed open the swinging doors.

The large interior had a fluorescent lamp hanging from a rotting tin ceiling. Its glare pierced thick veneers of smoke, through which I could make out faces of the toughest-looking men I had ever seen. They were leaning over the bar, drinking and eating. The group sported heavy jackets; most wore pea caps or wool hats. Metal grappling hooks dangled from their worn jackets, and some of the men leaning over the bar wore blood-encrusted aprons. The stark overhead lighting cast intense shadows across their hardened features.

Suddenly, a large man stepped forward and advanced within an inch of my face. Fixing me with an icy stare, he said, “Get the fuck out.” I was overcome with a deadly fear. That ended that. I was out on the street. The whole event took less than a minute.

For hours afterward, I couldn’t block out those unforgettable images. The ambiance inside the bar was tough and serious. It was an intense experience, even for a few moments, to be around those men. They were from another era in New York history when men had to earn a living in the most dire of circumstances, when the waterfront itself was shrouded in mystery. As a photographer, I had discovered gold.

The following night, I couldn’t sleep and decided to go back to the Paris. After midnight, I walked down Dover Street, a narrow street bordering the Brooklyn Bridge. A strong wind blowing from the river forced the metal shutters on the large anchorage windows to bang open and shut against the granite pillars. The sounds were unsettling. Then I came to South Street. The pale fluorescent light emanating from the bar windows cast deep shadows out into the street.

A bartender with sad eyes and a cigarette dangling from his lips looked up as I pushed open the doors once again. Noticing a camera tucked inside my unzipped jacket, he shook his head disapprovingly. Waving his hand, he signaled for me to approach the bar. He was well aware of the hostile looks from the men. Leaning over the shiny hand-carved wooden surface, he whispered in my ear, “Ya can’t stay, uh, it ain’t such a good idea. Come back durin’ the day.”

In the morning I went back. The bartender was still there, but the only customers were two old men hoisting a few whiskeys. While they drank, they were making lewd jokes. Then a few other men came in. They all seemed to know one another and took their places at the bar or sat at the 1940s-style tables and started drinking. I remember bits of conversation: “Well, Mikey, I’m up to no good today.” One of the men wore a nautical captain’s hat. He shouted some incoherent words as he kept drinking shots of whiskey. The time was approaching 9 a.m. A few more old-timers came in. They called each other by their last names. One was name...