![]()

| Child Sexual Abuse Legal Burdens and Scientific Methods KAREN M. STALLER AND FRANK E. VANDERVORT Down the road, they’ve got a program they call, “The Child Goes to Court” or something like that. Wrong! I mean, if we need our kid to go to court … we’ll get ’em ready…. But it’s a lot more effective if you bore in and get a legal confession that is presentable in court; [then] you don’t have to worry very much about preparing your kid to go to court. —Ed Duke, Chief of Police | ONE |

In his waning days as the prosecutor in St. Mary County, Mark Jameson stood one snowy morning in December 2002 before a jury and told its twelve members that in the next three days he would prove beyond a reasonable doubt that forty-eight-year old Tommy Inman had repeatedly sexually assaulted twelve-year old Takisha Johnson. Eight men and five women would hear the evidence against the defendant, much of it presented by the preteen girl, and decide Inman’s fate.

Inman was charged under state law with three counts of criminal sexual conduct (CSC) in the first degree. When Jameson, in his relaxed, plainspoken manner, explained to his fellow citizens that the evidence would show that this man committed separate acts of digital and penile penetration and forcing Takisha to perform fellatio upon him, he promised one of the law’s most difficult tasks: proving a criminal case of child sexual abuse (CSA) beyond a reasonable doubt.

“Beyond reasonable doubt” is a standard designed for a system that seeks to protect the innocent from being wrongly accused and convicted. If the scales must tip in favor of one side or the other, then in theory the legal system would prefer the guilty to walk free than deprive an innocent person of liberty. The power behind this presumption plays out in favor of the defendant throughout the process. The accused has the right to an attorney, the right to remain silent, the right to confront and cross-examine his accusers in a court of law, the right to a trial by a jury of his peers. Once in court, the burden rests on the prosecution to go well beyond establishing a plausible case, one supported by lower legal standards such as the preponderance of the evidence, and to convince the jury of the defendant’s guilt beyond reasonable doubt.

American prosecutors possess broad discretion in determining which criminal suspects should be charged and what charges to level (United States v. Armstrong). When they exercise this discretion, they must take into consideration the fact that in order to get a conviction they need to meet the beyond a reasonable doubt standard of evidence. This creates a margin of error in criminal charging. Unless the prosecution is convinced of a realistic opportunity to meet the standard, it will not typically charge a defendant (Kaplan, 1965). This helps to explain why the prosecution so rarely loses a case and provides one rationale for why so many criminal cases are resolved when the defendant pleads guilty—only cases with overwhelming evidence actually result in criminal charges. There is nothing untoward about this. Indeed, the American criminal justice system is designed to achieve just this result. The margin of error seeks to ensure that innocent people are rarely charged with a crime and that individuals should not be charged unless there is substantial evidence indicating guilt.

Unique challenges presented by CSA cases are layered atop this ever-present margin of error, and over the years children have paid a price as a result. Studies suggest that vastly larger numbers of children are victimized by adults (Berliner and Elliott, 2002) than are vindicated through criminal proceedings (Jones et al., 2007; Cross et al., 2007; Walsh et al. 2007; Walsh et al. 2008; Palusci et al., 1999; Martone, Jaudes, and Cavins, 1996; Cross, De Vos, and Whitcomb, 1994; MacMurry, 1988).

Writing in 1987, the United States Supreme Court observed, “Child abuse is one of the most difficult crimes to detect and prosecute, in large part because there often are no witnesses except the victim” (Pennsylvania v. Ritchie, 60). In order to prove such a case, a prosecutor must overcome a host of practical and legal problems: most cases of CSA leave no physical evidence, no injury that can be observed or detected by a medical examination (Palusci et al., 1999), and no bodily fluids that can be tested by forensic scientists.

The prosecutor must be able to convey a coherent legal narrative to the jury. Scholars have noted the significance of these legal narratives, “the resolution of any individual case in the law relies heavily on a court’s adoption of a particular story, one that makes sense, is true to what the listeners know about the world, and hangs together” (Scheppele, 1989:208). The “prosecutor must shape his or her client’s case into a coherent story” (Korobkin, 1998:10). In the case of child sexual abuse, the prosecutor must explain why children sometimes do not report their sexual victimization for months, even years; must help juries understand why, when children do report abuse, they may not tell the entire story in their initial disclosure, which can leave the uninformed juror with the impression that the child has embellished the story over time; and may need to make sense of why children sometimes recant valid disclosures of sexual abuse. They must somehow explain to average citizens what seems to be counterintuitive behavior on the part of some victims of CSA, such as why a child would run into the arms of the man who has hurt her or why a child’s description of sexual victimization may contain fantastical elements.

In short, the prosecutor must construct a believable legal narrative on behalf of a child victim, however, that child may not tell the story in a way that jurors can readily understand or may not act in accordance with adult expectations about truthful storytelling, thereby casting potential doubt (Korobkin, 1998; Lempert, 1991–92).

This is only a partial listing of the difficulties that must be overcome in proving such charges beyond a reasonable doubt. Defense attorneys stand ready to use each of these difficulties to their client’s benefit by sowing seeds of doubt about the child’s narrative and the strength of the prosecution’s case.

In the typical community response to a sexual abuse allegation, the child must make a forthright, detailed, and believable statement about the sexual abuse, which often requires the child to betray someone whom he or she loves and on whom he or she is dependent. This person may be perceived as powerful by the child, and may be able to provide a persuasive counterassertion that the child is lying, mistaken, or disturbed. Despite community intentions to minimize the number of times the child must repeat the account of sexual abuse, often children are repeatedly interviewed by a spectrum of professionals (Cross et al., 2007). This includes, when appropriate, submitting to a medical examination. If the child is convincing to professionals in the repeated interviews, and preferably if there are medical signs of sexual abuse or other evidence, the prosecutor may decide that there is sufficient evidence to prove the case and move forward.

Finally, the court system has its own series of burdens for the child. Usually the trial takes place after a number of procedural and other delays (Walsh et al., 2008). The child is either in a state of anticipation or prepares for the ordeal of testimony, only to have the trial postponed. Testifying involves not only direct examination, which demands yet another in-depth description of the sexual acts the child has experienced in the public or quasi-public environment of the courtroom, but also cross-examination, typically a face-to-face confrontation between the child and the defendant (Crawford v. Washington). A major goal of cross-examination is to discredit the child’s statement, memory, or intentions. Although in recent years states have passed statutes to make courtrooms more “child friendly,” often these measures are not invoked (see chapter 4). Moreover, none of these measures really do much to shift the burden of successful prosecution away from the child. Thus, the child is buffeted in a criminal-justice system designed by adults and primarily for adults. Their needs are routinely overlooked and unmet.

CSC AND THE ALLOCATION OF LEGAL AND SOCIAL RISKS

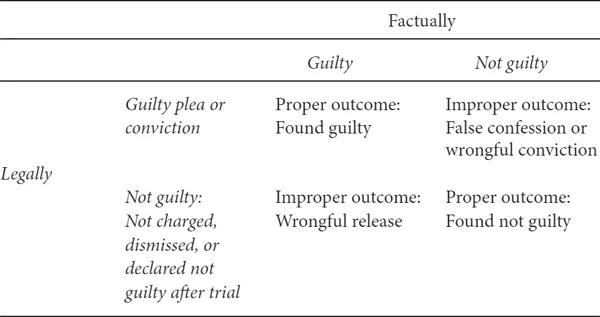

One way to make sense of these various discussions is to consider the distribution of legal and social risks and realities that potentially exist in any case and consider their implications. In general, there are four possible outcomes. They are reflected in table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Factual/Legal Outcomes

In any given case, as a matter of fact, the suspect either committed the acts or not, which may or may not be reflected in the finding of legal guilt. Oftentimes in CSA cases, only the two parties will know the absolute truth about what happened. Our criminal-justice system attempts to sort out the innocent from the guilty throughout the legal process. In doing so, the legal system either gets it right or gets it wrong. There are two possible ways of getting it right. First, the factually guilty either confesses or is convicted of a crime actually committed. Second, the factually innocent are not charged, their cases are dismissed, or they are found not guilty. Similarly, there are also two possible wrong outcomes. The first is when an innocent person confesses to something he or she did not do (false confession), or pleads guilty or is convicted of a crime that he or she did not commit (see chapter 8). The second is when a factually guilty person is not charged or convicted of crime that was committed. The burden of proof, constitutional rights of suspects, and margin of error in charging cases all speak to the preferred status of this type of legal error. As noted, an improper outcome resulting in a wrongful finding of innocence is the preferred error in our legal system to a wrongful finding of guilt. An error in this direction, however, may carry detrimental consequences that are particularly troubling in matters of child sexual abuse from a community perspective. Since CSA is often not a single isolated act, it means that a child victim may continue to be abused. Additionally, since abusers may assault multiple victims, letting a guilty person go free may mean that other children in the community are at risk. So from a legal perspective, while we may want to minimize the risk of making this kind of error relative to the suspect to protect our individual rights, from a social perspective we may be simultaneously increasing the risk of harm to children in the community.

Errors are certainly troubling in either direction. Nonetheless, professional practitioners (such as child advocates and defense attorneys) might well line up on opposing sides when discussing which kind of error is preferable from their professional standpoint and how they would balance the relative social and legal risks. This is particularly salient when tensions arise between two different professional points of view during the handling of a single case. Obviously, all criminal cases are about allocating the relative risks of these mistakes and protecting, as best we can, against abuses that would lead to any kind of wrongful outcome; nonetheless, how we balance these risks on a day-to-day basis has a direct impact on the operation of justice.

CHILD SEXUAL ABUSE: DEBATABLE PROGRESS

The St. Mary County circuit court judge who presided over the Inman trial recalled a case from his own days as the county prosecutor in the mid-1970s and used it to illustrate the difficulty in successfully prosecuting CSA cases. A ten-year-old boy spent a day with a family friend on his farm. At the end of the day, the boy’s mother observed her son emerge from the farmer’s truck and sensed almost immediately that something was wrong. She asked her son what was the matter. Within minutes, the boy explained that the farmer had molested him. The judge assessed the situation: “Well, I got a good case. First of all, I don’t have the problem of an untimely reporting. Second, there’s no problem about identification because the mother saw the man, knew the man. And third, the child’s demeanor reinforced his veracity.” Despite the perception of a strong case, the jury acquitted the farmer. The judge’s view was that this was because until relatively recently, the public had preferred not to acknowledge that sexually motivated crimes against children happen.

Support for the judge’s explanation of the jury’s response to this case is provided by the academic theoretical literature on “legal storytelling.” Among other things, Korobkin asserts that a critical factor linked to success at trial is the degree to which the legal narrative “reminds jurors of other stories, litigative or otherwise, that they accept as true.” Additionally, “litigative narratives—particularly the opening and closing arguments of counsel—utilize preexisting components familiar to their constructors from stories they have read, heard, watched, or told” (1998:13). Thus, to the extent that child sexual abuse was not characterized as a public problem in popular discourse until the late 1970s or early 1980s, the St. Mary prosecutor may have been attempting to frame his case around a legal narrative that was not yet understood or commonly accepted, or at least acknowledged as possible. Today, while publicly recognized, crimes of sexual violence against children are among the most underreported and infrequently prosecuted major offenses (Berliner and Elliott, 2002; Cross et al., 2002). Moreover, when prosecution does occur, in a large percentage of cases defendants are allowed to plead guilty to lesser offenses, oftentimes to charges unrelated to sex crimes (Gray, 1993). The difficulties inherent in prosecuting CSA and the resolution of these cases cause real problems for communities large and small.

Although some progress has been made in the prosecution of child sexual abuse since the late 1970s this progress has not been linear. By the early 1990s, there was grave concern in some quarters that law-enforcement authorities and child advocates had overreacted. These defense-oriented advocates argued that the criminal prosecution of alleged sexual victimization of children resulted in innocent persons being accused, convicted, and sentenced to long periods of incarceration. Their arguments were bolstered by a series of cases and appellate court decisions around the country that called into question a number of the methods used to investigate alleged CSA. Perhaps the most prominent of these is the McMartin preschool case from Los Angeles County, California. During the investigation, four hundred children who had attended the preschool over the previous decade were interviewed, and investigators concluded that 369 of them had been molested. Eventually, seven defendants were charged with 208 counts of sexual abuse upon forty-one children. A preliminary examination was conducted over the course of eighteen months, and at its conclusion, the seven were ordered by the court to stand trial on 135 counts. Shortly thereafter, prosecutors dropped all counts against five of the defendants, and two stood trial. Eventually the two defendants were either acquitted by a jury or the jury could not agree on guilt, and none of the defendants was ever convicted of any charge (Montoya, 1993).

In New Jersey v. Michaels (1993), the state Supreme Court overturned Margaret Kelly Michaels’s conviction of 115 sexual offenses that she had been convicted of perpetrating on twenty children in the Wee Care daycare center. The court’s concern about the way in which the child complainants were questioned by investigators resulted in the court’s mandating pretrial “taint hearings” to ensure that the child’s accounts of abuse were not contaminated by improper interviewing before they were permitted to be presented to a jury. These hearings are in practice today. As well, forensic narratives must be carefully collected in order to withstand subsequent scrutiny.

In another much debated example, the Country Walk case from Dade County, Florida, a couple was charged with molesting numerous children who attended the couple’s illegal daycare center. The wife, Ileana Fuster, pled guilty to twelve criminal counts of child sexual abuse and testified against her husband, Frank Fuster. A Honduran immigrant, she was sentenced to ten years in prison, then deported from the United States upon her release. Her husband was convicted of numerous counts of sexual battery and lewd and aggravated assault on children after a jury trial and sentenced to six consecutive life terms in prison, each with a minimum sentence of twenty-five years. Although this case began in 1984 and his trial was held in 1985, litigation upholding Frank Fuster’s multiple convictions and academic debate about the case continue a quarter-century later (Cheit and Mervis, 2007; Fuster-Escalona v. Crosby).

The tension brought about by differing views of such cases has led to a vigorous, long-standing, and multifaceted debate regarding how best to respond to alleged incidences of child sexual abuse. In the 1980s, when the intrafamilial sexual abuse of children was just emerging as a recognized public problem, prosecutors were initially reluctant to bring charges, believing that such cases were more appropriately resolved through civil child-protective proceedings in family and juvenile courts (Ginkowski, 1986). They were primarily thought to be private family affairs, and prosecutors expressed concern that intervention by the criminal courts would not be effective. Today CSA, whether within the family or not, is prosecuted more vigorously. More vigorous prosecution has, in turn, spurred a contentious debate in mental health, social services, and legal communities about various aspects of investigation, assessment, and charging decisions (Ceci and Bruck, 1995; McGough, 1995, 2002; McGough and Warren, 1994). About this debate, Jane Mildred has aptly observed that “well-known and respected scientists with impressive credentials disagree about almost every important issue ...