![]()

PART I

COMMUNITY PRACTICE: PURPOSE AND

KNOWLEDGE BASE

Our goal in writing this book is to provide community practice workers with a comprehensive guide to skills for practice and with a knowledge base drawn from the values, purposes, and theories that form the foundation for work with communities. To help workers understand and differentiate among a range of intervention methods and skills for effective practice, we have developed a framework of eight different models illustrating approaches focused on specific goals. Our discussion for each model includes guidance for effective engagement and ethical practice, with examples drawn from both the United States and international contexts. This material will be useful not only to social workers but also to a wide range of community workers, including those involved with public health, city and regional planning, community sustainable development, and community capacity building.

We write from extensive experience in community practice with grassroots groups, community-based organizations, and the education of social workers in both the United States and international settings. Our primary interest is in expanding the work of anyone involved in building the capacities of community members and community institutions to improve the quality of life for people in community—whether that community is local or part of an extended regional, national, or global group.

We begin with a discussion of communities and community practice in the local to global continuum. In chapter 1, we discuss the meaning of community, processes associated with community practice, and social justice and human rights as the values that are the central focus of community practice. Chapter 2 presents the table of eight models of community practice, the rationale for their development, a discussion of the “lenses” we believe will significantly influence the context of community practice in this century, and the roles associated with the different models of practice. Chapter 3 presents a broader discussion of guiding values and the evolution of the purposes and approaches to community practice. Building from that discussion, chapter 4 provides an overview of the concepts, theories, knowledge, and perspectives that guide community practice. Part II of the book, encompassing chapters 5–12, focuses on the scope of concern, basic processes, conceptual understandings, and roles and skills important for practice in each model. The companion volume, Community Practice Skills Workbook (Weil, Gamble, and MacGuire 2010; hereafter cited as the CPS Workbook), provides additional opportunities to engage in skill development with each model.

Issues of human rights and social justice are explored in each of the eight models of community practice analyzed in this volume. We are committed to building competencies and skills for social justice among future community social workers in all parts of the world. This commitment stems in part from the historical and heroic role of so many people who came before us and who showed the way to a more just society. We have learned lessons from Sojourner Truth, a courageous abolitionist born into slavery in New York in 1797, sold from her family at age 11, and yet spent the rest of her life working tirelessly for the freedom of slaves and the rights of women; from Jane Addams and her early work with families and organizations in Chicago’s industrial slums; from Rosika Schwimmer, the Hungarian social worker and suffragist who worked with Jane Addams toward mediation to end the World War I hostilities and later fled to the United States when Jews were purged from Hungary, only to be denied U.S. citizenship because she was a pacifist; from Eleanor Roosevelt, who was instrumental in developing the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; from Mohandas Gandhi, who led the people of India in mass civil disobedience to a peaceful revolution, bringing them freedom and independence from Great Britain; from Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta, who built an organization to protect the rights of farm laborers throughout the United States; from the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., whose message of freedom and peace still guides all people working against oppressive policies; from Nelson Mandela, who, even after spending twenty-eight years in prison, led his country on a path toward truth and reconciliation when South Africans at last overthrew apartheid and elected him to be their president; and from Wangari Maathai and Vandana Shiva, who connected our understanding of environmental restoration with women’s rights and social justice in Kenya and India, respectively. There are so many more whose names may not be as well known, but whose deeds and words provide the guidance and wisdom to move human rights and social justice forward (Brueggemann 2006; Carlton-LaNey 2001; Maathai 2004; Mandela 1995; Shiva 2005).

These beacons of hope from both the past and today can be added to the list of people from your own life who have inspired you to work for social justice and human rights. Reflecting on such legends and inspirational models helps us get through the difficult times and keep our focus on the long term as we work to build democratic processes and empowered communities. Reflecting on the work of those who embody practice excellence can also help each of us develop our own essential skills that will be grounded in empowerment practice, human rights, and social justice.

![]()

1

COMMUNITIES AND COMMUNITY PRACTICE

IN LOCAL TO GLOBAL CONTEXTS

Snowflakes, leaves, humans, plants, raindrops, stars, molecules, microscopic entities all come in communities. The singular cannot in reality exist.

PAULA GUNN ALLEN, AUTHOR OF THE SACRED HOOP AND POCAHONTAS

THE MEANING OF COMMUNITY IN THE LOCAL

TO GLOBAL CONTINUUM

The meaning of community varies with each new generation, each distinct geographic location, and each community of interest. Scholars in the areas of sociology, psychology, anthropology, history, philosophy, and social work have all explored the meaning of community (Creed 2006; Martinez-Brawley 1995; Park 1952; Stein 1960; Warren 1963, 1966). Community can evoke the image of the traditional, bucolic village drawn from Ferdinand Tönnies’s classic work that described small rural communities as characterized by gemeinschaft—that is, close-knit, face-to-face relationships imbued with a sense of mutual responsibility and obligation. Or community can call forth Tönnies’s contrasting image, gesellschaft—that is, mechanistic relationships found in the growing industrial cities and characterized by larger, impersonal networks, broader working and exchange relationships, and weakened local ties (Tönnies, 1887/1957).

In small-scale geographic settings, bioregional location, socioeconomic as-sets, and cultural and political currents influence the human relationships and networks that give our lives meaning and purpose. These relationships and networks can be variably supportive or oppressive, depending on how inclusive and welcoming the accepted social, cultural, economic, and environmental norms are toward diverse individuals and family groups. Today, both the supportive and oppressive aspects of small-scale communities are inescapably affected by global political and commercial activity that may be initiated in faraway places.

In many parts of the world, elements of traditional, small-scale local communities remain very much alive, and supportive social and economic networks provide a basic community foundation. Today, however, we live in a world with unprecedented capacity for communication and travel that is expanding both our personal opportunities and our views of our local communities. Urban communities are exerting a strong pull as more people move to urban areas every year. By the year 2050, the United Nations predicts that 70 percent of the world’s population will be living in urban areas (International Herald Tribune, February 26, 2008).

When the Apollo Mission astronauts sent the world the first photographs of Earth from space, most of us internalized the image of that beautiful blue marble as our home and “community.” In that transformational moment, many began to think of community globally and to understand the larger sense of community as the interconnection of all living systems on Earth. From the perspectives of First Nation peoples and spiritual leaders, however, the interconnections go even deeper and wider across time and space (Berry 1990; LaDuke 2005). The rapid advances in technology and media have fostered this larger view of community by giving us instant access to events and images from around the world. This global access allows us to perceive that we are directly affected by each other’s activity—whether that activity is downriver, downwind, across mountains, beyond borders, or across continents. Technology also helps us to create communities of interest, which connect people who wish to belong together because of loyalty and self-identification, and functional communities, which join people together in common causes for purposeful change in social, economic, and environmental arenas (Fellin 2001; Garvin and Tropman 1992; Park 1952).

William G. Brueggemann (2006) described community as

natural human associations based on ties of intimate personal relationships and shared experiences in which each of us mutually provide meaning in our lives, meet our needs for affiliation, and accomplish interpersonal goals… . Our predisposition to community ensures that we become the persons we were meant to become, discover who we are as people, and construct a culture that would be impossible for single, isolated individuals to accomplish alone. (116)

In rural traditional communities, these relationships may encompass an entire village, whereas in townships, cities, and megacities, a sense of community is more likely to relate to a neighborhood, workplace, or other smaller geographic or functional grouping.

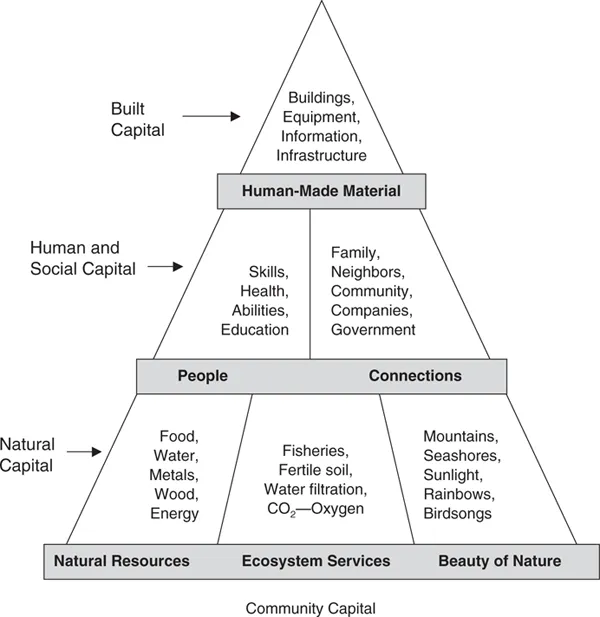

COMMUNITY COMPONENTS

Maureen Hart’s practical picture of community incorporates social interaction and natural resources to describe the raw materials from which we create the social and economic aspects of community (Hart 1999). Hart’s Community Capital Triangle (see figure 1.1) describes community as a three-level pyramid that includes natural capital, human capital, and built capital. Natural capital forms the base of Hart’s model and contains three systems: (1) natural resources, such as food, water, minerals, wood, and energy; (2) ecosystem services, including fisheries, fertile soil, water filtration, and carbon dioxide; and (3) the beauty of nature, such as mountains, seashores, sunlight, rainbows, and bird songs. In the pyramid’s second level, human and social capital, Hart defined two categories: (1) people, which includes their skills, health, abilities, and education; and (2) connections, which includes relationships of family, neighbors, community, companies, and governments. At the top of the pyramid, supported by the other five building blocks, is what Hart calls built capital, which is composed of all the things humans make and produce (e.g., buildings, equipment, information, infrastructure, art, music, clothing, roads). Hart’s picture of community capital helps us understand the relationships between the resources available to community members and the way our communities can strengthen or preserve those resources.

FIGURE 1.1 Hart’s Community Capital Triangle

Source: Maureen Hart (1999), Guide to Sustainable Community Indicators, 2nd ed. (North Andover, MA: Hart Environmental Data), p 16. Available from Sustainable Measures. www.sustainablemeasures.com. Used with permission.

KENYA CHILE

For the past thirty years, all over Kenya, Wangari Maathai, winner of the 2004 Nobel Peace Prize, has provided leadership to the Green Belt Movement with the aim “to mobilize communities for self-determination, justice, equity, poverty reduction, and environmental conservation, using trees as the entry point” (Green Belt Movement 2006). The Green Belt Movement has organized numerous community networks that are now caring for 6,000 tree nurseries across Kenya. These community networks have already planted more than 30 million trees throughout Kenya, transforming not only the environment but also attitudes about the future and thoughts of how to shape it. Currently, the Green Belt Movement has projects that move beyond Kenya’s borders and that are continuing the mission of working with ordinary people to improve their lives and future, using tree planting as the motivational beginning point for community development and citizen involvement.

CHILE

For fifty years, and under widely divergent national governments, residents of La Victoria, a poor neighborhood on the edge of Santiago, Chile, have struggled to find meaning and justice in their lives. Even during the dark years of the Pinochet regime with its concentrated military effort to crush any popular movement, ordinary citizens continued to organize and to break down the fear created by the military. For example, during the Pinochet years, the people of La Victoria organized a huge outdoor tea on March 8 to mark International Women’s Day. The women of La Victoria were seated at tables that stretched down the entire street, while the town’s men and children served the tea and snacks that they had cooked in church kitchens. The people of La Victoria seized this and every other opportunity to have a public celebration, and in so doing, they “reclaimed symbolic power as they rejected the regime’s imposed reality,” thereby creating “spaces of possibility and resistance in the face of powerfully determining forces.”

(Finn 2005:22)

COMMUNITY PRACTICE EXAMPLES

How do we engage with a community, in either a local or a global context, to work toward community improvement? Each of the boxed examples in this chapter provides a brief description of community from the perspective of people interested in community practice, whether in professional capacities or as neighborhood leaders. Although these examples focus primarily on local communities, they recognize connections to a larger environment, and some acknowledge both the past and present forces that are part of their experience.

CHINA

In Guangzhou, a large city in the Guangdong Province of South China, more than 12 percent of the population is comprised of older adults, and 365 people are officially recorded as 100 years or older. To meet the needs of the growing population of older adults, especially older women, both the national and provincial governments are working with the families, who have traditionally been responsible for care of older relatives. Although much remains to be done to meet the needs of China’s older adults, especially those living in rural areas, the provincial administration has shown a remarkable commitment to making adult services a priority. Already, adult services centers have been built in every neighborhood and district within Guangzhou city. The goal of these centers is to provide social, educational, recreational, health care, and respite care for the older adults and their families.

(Lee and Kwok 2006)

UNITED STATES

The nonprofit South Eastern Efforts Developing Sustainable Spaces (SEEDS) program in Durham, North Carolina, has been working to build community, neighborhood by neighborhood. SEEDS workers establish neighborhood programs that teach gardening, cooking, educational, and art skills to the children, youth, and adults of Durham. The overall goal of the SEEDS programs is to teach “respect for life, for earth, and for each other” (City Farmer 2006). The neighborhoods served by SEEDS are composed of a mix of African American, Latino, and Anglo families, reflecting the city’s recent population changes. Children in the “Seedlings” program plant snow peas, and later carrots and onions, both to eat and to sell at the local farmers’ market. Parents and other volunteers build raised gardening beds,...