eBook - ePub

Available until 27 Jan |Learn more

Achieving Permanence for Older Children and Youth in Foster Care

This book is available to read until 27th January, 2026

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 27 Jan |Learn more

Achieving Permanence for Older Children and Youth in Foster Care

About this book

Through a novel integration of child welfare data, policy analysis, and evidence-informed youth permanency practice, the essays in this volume show how to achieve and sustain family permanence for older children and youth in foster care. Researchers examine what is known about permanency outcomes for youth in foster care, how the existing knowledge base can be applied to improve these outcomes, and the directions that future research should take to strengthen youth permanence practice and policy. Part 1 examines child welfare data concerning reunification, adoption, and relative custody and guardianship and the implications for practice and policy. Part 2 addresses law, regulation, court reform, and resource allocation as vital components in achieving and sustaining family permanence. Contributors examine the impact of policy change created by court reform and propose new federal and state policy directions. Part 3 outlines a range of practices designed to achieve family permanence for youth in foster care: preserving families through community-based services, reunification, adoption, and custody and guardianship arrangements with relatives. As growing numbers of youth continue to "age out" of foster care without permanent families, researchers, practitioners, and policymakers have increasingly focused on developing evidence-informed policies, practices, services and supports to improve outcomes for youth. Edited by leading professionals in the field, this text recommends the most relevant and effective methods for improving family permanency outcomes for older youth in foster care.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Achieving Permanence for Older Children and Youth in Foster Care by Benjamin Kerman,Madelyn Freundlich,Anthony Maluccio, Benjamin Kerman, Madelyn Freundlich, Anthony Maluccio in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Work. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

| Describing the Problem | PART I |

A necessary foundation for the development of a successful policy and practice response to the permanence needs of youth in foster care is an accurate and detailed description of the challenges. It is essential to clearly frame the problem, specify the questions that must be answered in order to develop sound policy and practice, and use data to address those questions as fully as possible. Only through clarifying what is known and what needs to be known is it possible to set priorities within policy and practice and identify the needed levers for change.

Historically, national child welfare data have been limited. Until the mid-1990s, states were asked to voluntarily provide child welfare data through the Voluntary Cooperative Information System (VCIS). There were limited outcome studies regarding youth in foster care, and in few studies were the voices of youth sought as a source of information about youth's experiences and outcomes in foster care. Foster care and adoption data, however, have become more available since the mid-1990s with implementation of the Chapin Hall Multi-State Foster Care Data Archive and the federal Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS). At the same time, certain broad-based studies seeking the perspectives of youth have examined the outcomes for youth who age out of foster care.

Fred Wulcyzn and Penelope Maza use two major sources of child welfare data to help clarify the challenges associated with youth permanence and to describe some of the dynamics that shape the experiences and outcomes of youth in foster care. In chapter 1, Wulcyzn uses data from the Chapin Hall archive to answer several questions: Who grows up in foster care, and what portion of their childhood was spent in a foster home or some other placement setting? Where do adolescents fall within the broader context of children entering foster care for the first time? Are there entry rate disparities for white children and black children when age is taken into account? How do youth leave foster care: that is, what portion of youth leave through reunification, adoption, aging out, and running away? In chapter 2, Maza uses AFCARS data to identify the similarities and differences between youth who achieved and who did not achieve permanence. She examines various factors that are associated with permanence, including gender, race/ethnicity, placement history, length of stay, and age at time of removal. using a different data repository, her findings triangulate on similar themes and lend credence to the conclusions, despite the limitations of looking across states’ administrative data.

The growing body of outcome research has contributed to a fuller understanding of the poor outcomes for many youth who leave foster care to live on their own. The research contributes to the great sense of urgency that policy and practice respond more effectively to the needs of youth in foster care, particularly those who age out to “independent living.” in chapter 3, Mark Courtney provides a concise but comprehensive review of the findings from twenty-two studies with samples of youth who had aged out of foster care. These findings make clear that, on average, young people who age out of foster care are significantly disadvantaged across a number of domains as they approach and later negotiate the transition to adulthood. The studies also demonstrate that youth in foster care are much less likely than their peers to be able to rely on family for support to compensate for their disadvantages during the transition. In chapter 4, Peter Pecora responds, discussing two additional, recently completed studies and highlighting some of the most pressing needs facing youth who have exited foster care. Both Courtney and Pecora discuss the implications of the research findings for policy, program, and practice improvements.

Progress in child welfare research is impeded by lack of conceptual models that can be tested. In chapter 5, Richard Barth and Laura Chintapalli suggest one such model. They propose a model for understanding the relationships among placement instability, youth's emotional and behavioral problems, administrative decisions, disconnection from family, and placement into residential care. in particular, they examine instability in care and the use of congregate care facilities as impediments to permanence, and they describe the challenges of “impermanent” permanence when reunifications are not successful and when termination of parental rights does not lead to adoption.

In response, in chapter 6, Gretta Cushing and Benjamin Kerman spotlight the need for clarity around the dimensions of permanence that further reflect on the ultimate goal of family connections. They urge that the discourse regarding research, interventions, and policy extend beyond legal permanence and incorporate a recognition of the vital role that nurturing parental connections plays in youth development, irrespective of whether the relationships are formally recognized with legal sanction. With a focus on emotional security and belonging, they explore the practice, policy, and research implications of viewing permanency as a “state of security and attachment.”

| Foster Youth in Context FRED WULCZYN | ONE |

According to national statistics, upward of twenty thousand children left foster care in 2002 after their eighteenth birthday; among children in care, emancipation was listed as the case goal for more than thirty-four thousand children (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2007). Not surprisingly, the issue of foster youth has attracted considerable attention, particularly over the past decade since the beginning of the twenty-first century. For the most part, that attention has focused on the transition to adulthood by children who reach the age of majority while still in foster care (that is, while in state custody). Policymakers at the federal level have addressed the problem at least twice. The independent living act of 1985 established a pool of federal resources for youth leaving foster care. more recently, the Foster Care independence act of 1999 (the Chafee act) renewed the focus on children leaving foster care and their preparation for adulthood.

Despite the policy attention, relatively little empirical work has been done to place foster youth (children age thirteen and above) in the broader context of the foster care system. Discussions of foster youth often begin with an image of children who grow up in foster care only to face the transition to adulthood without the benefit of any social connections. Although that is a powerful image, the pathways that adolescents take through the foster care system are often more complex. This chapter addresses a set of basic questions designed to broaden our understanding of adolescents within the foster care system. The first question deals directly with the issue of who grows up in foster care and the portion of childhood that they spent in foster care. The second question relates to the entry of children into foster care, with specific attention to where adolescents fall within the broader context of children entering foster care for the first time and entry rate disparities for white children and black children that take age into account. The third question relates to youth's exits from foster care. youth placed in foster care leave care for a variety of reasons that include reunification, adoption, aging out, and running away.

Foster youth, as described in this chapter, generally refers to children between the ages of thirteen and seventeen. The definition, however, is flexible, depending on the context. From an admission perspective, a definition of foster youth as children between the ages of thirteen and seventeen is workable; from a discharge perspective, it is better to expand the definition to include individuals leaving care at eighteen and older. For other questions, it is useful to consider the experience of children admitted before they turned thirteen.

GROWING UP IN FOSTER CARE

The issue of youth aging out of foster care has gained salience for the reason that the state has an obligation to shape successful transitions to adulthood for these youth. Because the state has care and custody of the child, it must, as any parent is expected to do, see to it that foster youth have the requisite assets needed to complete a successful transition to adulthood.

Although who grows up in foster care is a straightforward question, very few empirical data are available to answer it. Moreover, from the data that are available, it is difficult to say whether growing up in foster care has become more or less likely over time. The paucity of data is attributable to the fact that, in all but a few states, there are no administrative data that allow the tracking of outcomes for children who entered foster care as young children. as an example, most states do not have data that answer a question such as the following: Of children admitted as babies in 1986, how many spent their childhood through age eighteen in foster care, leaving care in 2004? The same challenges remain in answering questions about children who were admitted to foster care in 1987 at one year of age or older and who may have spent what was “left” of their childhood in foster care once they were placed. Time spent in foster care for these children, however, would represent a declining portion of their childhood, if childhood were measured from birth through age eighteen. Moreover, with each passing year from 1987 through 2004, less and less would be known about how much time was spent in foster care relative to childhood in its entirety because the group of children whose eighteenth birthday has been observed is smaller as time moves closer to the present.

Fortunately, a handful of states have data from 1986 that provide a preliminary answer to this important question. Even with these data, it is difficult to identify trends as from 1986 to the present. There have been a number of policy initiatives designed to influence outcomes for children in foster care. some children placed in foster care in 1986 were in care when each of these policies was put into place by law. For other children, only some of the policy changes would have affected their placement experiences and outcomes.

For this analysis, we look at all children admitted to foster care for the first time from 1986 through 2004. The total number of children is 701,233; the number of children who aged out of placement (that is, were in foster care on their eighteenth birthday and left foster care at that time) is 35,979, or about 5 percent of the total. It is possible to know whether a child aged out of foster care only if we observe the child's eighteenth birthday. For other children admitted since 1986, we will not observe their eighteenth birthdays as of 2004. As these birthdays are observed, the 5 percent will grow over time.

For children admitted as babies, we look at 1986–1987 data to answer the question of how likely it is that a child will spend his or her entire childhood in foster care. The question of how many babies age out of foster care is important because babies make up the largest group of children admitted since 1986. Of the total 701,233 children admitted to foster care, babies accounted for 150,000, or about 20 percent. Unfortunately, relatively little is known about these babies. As noted earlier, only babies from the 1986 entry cohort have been alive long enough to determine whether they were still in foster care upon reaching their eighteenth birthday. The number of babies who aged out is very small. Notwithstanding sources of error in the data (e.g., children who moved to other states or were otherwise lost to the tracking system), only twenty-five children stayed in foster care for their entire childhoods, a figure that represents about one-half of 1 percent of the five thousand infants admitted in 1986.

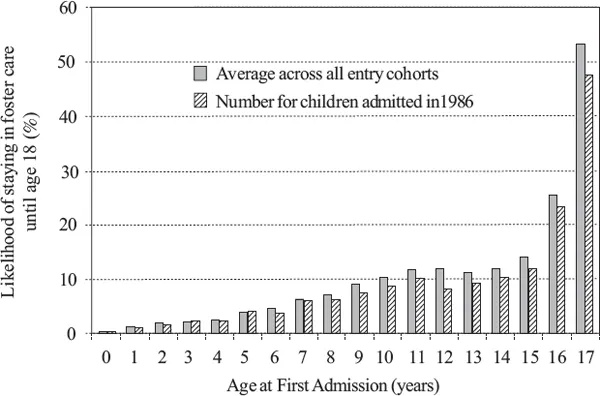

Figure 1.1 Percentage of children aging out of foster care by age at admission, 1986–2004 admissions

In Figure 1.1, data representing the likelihood of entering care and staying in foster care until age eighteen by age at first admission are given for all children between the ages of birth and seventeen. Two sets of data are displayed: the average across all entry cohorts and the specific figures for children admitted in 1986. When viewing the data, it is important to bear in mind that the sample used to compute the average grows by one year with each age group. The figure for babies represents the experience of babies admitted in 1986, the only year for which data are available. For one year olds, there are two years of data available: 1986 and 1987. For seventeen year olds, there are seventeen years of experience to consider, given that any child who entered foster care at seventeen would have been observed to age out if, in fact, they did.

The data show that through age six, fewer than 5 percent of the children in each age group admitted remained in their first placement spell through their eighteenth birthday. Among children between the ages of one and ten, the comparable figure was between 6 and 10 percent. For children between the ages of eleven and fifteen, the percentage of children who aged out was between 11 and 14 percent. The percentage of children who aged out was hi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- PART I: Describing the Problem

- PART II: Policy Responses to the Permanency Needs of Youth

- Part III: Practice Responses to the Permanency Needs of Youth

- Afterword: Making Families Permanent and Cases Closed—Concluding Thoughts and Recommendations

- List of Contributors

- Index