![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

Famine, Aid, and Markets in North Korea

Beginning sometime in the early 1990s and extending into 1998, North Korea experienced famine. We estimate that the great North Korean famine killed between six hundred thousand and one million people, between 3 and 5 percent of the entire population of the country. Such events are national traumas that live in the collective memory for generations. Famines produce countless personal tragedies: watching loved ones waste away from hunger and disease; making fateful choices about the distribution of scarce food; migrating to escape the famine’s reach; and, all too often, facing the stark reality that these coping strategies are futile. A full understanding of such disasters can only be communicated through their human face: the individual experience of the suffering and humiliation that extreme deprivation brings to its victims. Through refugee accounts, this human face of the North Korean famine is slowly becoming available to us and speaks far more eloquently than we can here.

But famines also have causes as well as profound demographic, economic, and political consequences for the societies that experience them. Despite its rigidly authoritarian and closed nature, North Korea is no exception to this rule. The purpose of this book is to explore the political economy of this great famine through a number of different but ultimately complementary lenses. What does the North Korean case say about the causes of famines more generally? What lessons does it hold for the humanitarian community? What does it say about the transition from socialism? And how have recurrent food shortages played into the security equation and political dynamics on the Korean peninsula?

Sadly, our concerns are not simply historical ones, and we were first brought to these issues by contemporary concerns (Haggard and Noland 2005). As in far too many cases, famines are not necessarily followed by a return to abundance. Rather, the acute shortages of the mid-1990s turned into a chronic food emergency that persisted well into the first decade of the 21st century. Despite the efforts of the international humanitarian community, and despite—and even because of—a set of wide-ranging but ultimately flawed economic reforms, large portions of North Korea’s highly urbanized society suffer from unreliable access to food. North Korean families continue to experience the ravages of malnutrition, most painfully evident in the admittedly partial and imperfect information we have on the nutritional status of children over time.

Famines bear a curious resemblance to genocides. As Samantha Powers (2002) has pointed out, outsiders’ first response to genocides is denial. Given the horror of events, the natural reaction is that it can’t be happening; it is not possible. During genocides, however, delay is fatal; where there is a will, masses of people can be killed quickly. Similarly, while we can procrastinate about many things, we cannot go for long without adequate sustenance (see Russell 2005). By the time the evidence of famine is clear, it is often too late to reverse its effects, and the worst damage has been done.

Yet the humanitarian effort in North Korea faced additional barriers. Until a series of great floods in the summer of 1995, the North Korean government was slow to respond to the warning signs that a famine was under way. The closed nature of the country made it even more difficult for outsiders to read the signals.

Once aid was fully mobilized in 1996, the North Korean government proved deeply suspicious of foreign intent and has to this day thrown roadblocks in the way of the relief effort. The delivery and monitoring of humanitarian assistance to North Korea is an ongoing negotiation and struggle, and for a good reason: there is ample evidence of things to hide. Large amounts of aid—we estimate as much as 30 percent or more—is diverted to the military and political elite, to other undeserving groups, and to the market.

Floods, subsequent natural disasters, and the hostile policy of outsiders constitute the official explanation for North Korea’s food problems. Yet the chronic nature of North Korea’s problems suggests that forces more systemic were at work. These included failed economic and agricultural policies but also a particular system of entitlements associated with the socialist economy and a political system that provided no channels for redress when these entitlements failed. Following the pioneering work of Amartya Sen (1981; 2000: chap. 6; Dreze and Sen 1989), we suggest throughout this book that the ultimate and deepest roots of North Korea’s food problems must be found in the very nature of the North Korean economic and political system. It follows almost as a matter of logic that those problems will not be definitively resolved until that regime is replaced by one that, if not fully democratic, is at least more responsive to the needs of its citizenry.

As we have suggested, however, the famine was not without its own consequences, and one of them was an increasing marketization of the economy and, beginning in 2002, the initiation of economic reforms. Marketization and reform remain the key unfolding story in the country, a work-in-progress that contains the small glimmers of hope we can hold out for an economically if not politically reformed North Korea. Yet through 2005 these signs of change remained largely hopes. The initiation of reform overlapped with renewed international political conflict over North Korea’s nuclear ambitions—a crisis largely of North Korea’s own making—which in turn had predictably mixed effects on the reform effort.

Moreover, the reforms themselves failed to return the country to sustainable growth and unleashed a stubborn inflation that contributed to the ongoing food problems in the country. By this time, North Korea was a society increasingly divided between those with access to foreign exchange and stable supplies of food and those vulnerable to an erratic public food distribution system and markets providing food and other goods at prices beyond the reach of the ordinary citizen.

We divide our account into three broad questions. In part 1 (chapters 2 and 3), we consider the contours of the famine of the mid-1990s: its underlying and proximate causes and its trajectory and more immediate consequences, including mortality. In these chapters, we are speaking both to a broader literature on famine and to important accounts of the North Korean case, on which we build.1 The second section (chapters 4 and 5) is devoted to a discussion of the political economy of humanitarian assistance. These politics involve the humanitarian community and its norms, the political as well as economic interests of the North Korean government, and the sometimes congruent, sometimes conflicting interests of the donor governments. In the third section (chapter 6), we look at the famine through yet a third lens: what it says about North Korea as a socialist economy undergoing some sort of transition. The famine ultimately triggered a process of economic reform in the North. But as we now know from nearly twenty years of “transitology,” the route to the market is not linear but strewn with partial reforms and a variety of intermediate models of which North Korea is certainly one.

In the remainder of this introduction, we outline these themes in somewhat more detail, returning in the conclusion to some of the broader policy issues posed by North Korea’s famine and food shortages (the subject of chapters 7 and 8 in part 3). Before turning to those themes, however, we sketch a few features of the country’s political history. Although this survey is admittedly cursory, we reference a number of works where these issues can be pursued in greater depth and focus primarily on those background conditions that are germane to our story.

The Setting

At the conclusion of the Second World War, the Japanese colony of Korea was partitioned into zones of U.S. and Soviet military occupation.2 Unable to agree on a formula for a unified Korea, the Republic of Korea (ROK, or South Korea) declared independence under U.S. patronage in 1948, while the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, or North Korea) was established under Soviet tutelage. In June 1950, North Korea invaded South Korea. The initial success of the invading forces was reversed with the support of a U.S.-dominated United Nations force, which in turn drove China to enter the war in October to prevent a North Korean defeat. Combat ended with an armistice in 1953. After tremendous physical destruction and loss of life, the war did little more than reestablish the original borders. No formal peace treaty was ever signed, and the combatants technically remain at war.

Kim Il-sŏng fully consolidated his power over rival factions in the DPRK after 1956 and began to articulate a distinctive national ideology called chuch’e (Armstrong 2002 and Lankov 2002). Typically translated as “self-reliance,” North Korean ideology in fact combines a number of elements—extreme nationalism, Stalinism, even Confucian dynasticism—into a complex mix (Cumings 2003; Oh and Hassig 2000). The political order has exhibited a high degree of personalism. Kim Il-sŏng was deified as the “Great Leader.” Similar efforts have been made to canonize his son, Kim Jŏng-il, who assumed the reins of political power when his father died in 1994.

Personalism was combined with an extreme, even castelike social regimentation. The government classified the population—and kept dossiers on them—according to perceived political loyalty and even the social standing of parents and grandparents. The share of the population deemed politically reliable is relatively small, on the order of one-quarter of the population, with a core political and military elite of perhaps two hundred thousand, or roughly 1 percent of the population.3 As we will show, this political-cum-social structure also has important implications for the distribution of food and other goods.

A further feature of the political and economic system is extreme militarization (Kang 2003). By standard statistical measures such as the share of the population under arms or the share of national income devoted to the military, North Korea is the world’s most militarized society. The bulk of its million-strong army is forward-deployed along the demilitarized zone (DMZ) separating it from South Korea, a highly destabilizing military configuration. Viewed with the benefit of hindsight, the division of the peninsula has proven surprisingly stable; a recurrence of full-scale war has been avoided. Yet underneath this apparent stability is a history of sustained military competition and recurrent crises. Moreover, militarization has important domestic effects. During external crises, the government reverts to sŏn’gun, or “military-first” politics. As we will argue, the expenditure priorities of the regime are also an important aspect of the hunger story, and the question of diversion of humanitarian supplies to the military is an ongoing political issue among donors.

In the early 1990s, North Korea experienced a rapid deterioration in its external security environment. The collapse of the Soviet Union and the ongoing reform efforts in China put North Korea at odds with its two most important patrons. The continued dynamism of the South Korean economy made it more and more difficult—and costly—to maintain the illusion of military parity. The acquisition of nuclear weapons no doubt seemed an inexpensive way to address these insecurities but resulted in a major crisis with the United States in 1992–94 (Sigal 1998; Wit, Poneman, and Galucci 2004). The nuclear crisis and the question of food aid became inextricably linked, but in unexpected ways, as the provision of assistance was used to induce North Korean participation in diplomatic negotiations. Similar issues arose after the 2002 nuclear standoff as the main aid donors—the United States, Japan, China, South Korea, and the European Union—diverged on how to deal with North Korea’s nuclear ambitions; we return to these issues below.

Despite claims of self-reliance and the extremely closed nature of the economy, international assistance has long been crucial to North Korea’s very survival. Before the 1990s, North Korea depended both militarily and economically on Soviet largesse. China subsequently has come to play a more important role. From a balance-of-payments standpoint, it appears that North Korea now derives roughly one-third of its revenues from aid, roughly one-third from conventional exports, and roughly one-third from unconventional sources (in estimated order of significance, missile sales, drug trafficking, remittances, counterfeiting, and smuggling; see appendix 1). The remittances come mostly from a community of pro-Pyongyang ethnic Koreans in Japan and increasingly from refugees in China, who may number one hundred thousand or more (KINU 2004).

North Korea is characterized by a complete absence of standard political freedoms and civil liberties. The political system is completely dominated by a deified leader, with the military complex, the Korean Workers’ Party, and the state apparatus playing supporting roles that have shifted in importance over time. Independent political or social organizations are not weak in North Korea; they are virtually nonexistent. Any sign of political deviance, from listening to foreign radio broadcasts to singing South Korean songs to inadvertently sitting on a newspaper containing the photograph of Kim Il-sŏng, can be subject to punishment. Until the famine forced their breakdown, the government maintained complex controls on internal migration and foreign travel and even criminalized the very coping behaviors through which families sought to secure food.

The regime maintains a network of political prison camps that hold two hundred thousand or more political prisoners (Hawk 2003; KINU 2004; Kang 2002, a memoir by one camp survivor). Death rates in these camps are high, torture is practiced, and there are numerous eyewitness accounts of public executions, including cases of schoolchildren being forced to witness these killings (see United States Department of State 2005, Amnesty International 2004, and KINU 2004). A second network of smaller extrajudicial detention centers developed as an ad hoc response to coping behavior at the height of the famine, which included unauthorized internal movement and crossing into China.

In sum, the North Korean case exhibits a number of features that make it a particularly difficult target for humanitarian efforts. In contrast to civil war settings, the government exercises complete control over its territory. It has a well-developed ideology that has until recently been highly impervious to reform or outside advice. The political leadership exhibits an extreme wariness toward outside influences of any sort, a posture justified by an increasingly adverse security setting. These characteristics not only make North Korea a hard target for humanitarian assistance, but they help explain some of the underlying and proximate causes of the famine as well.

The Great Korean Famine: Causes, Trajectory, Consequences

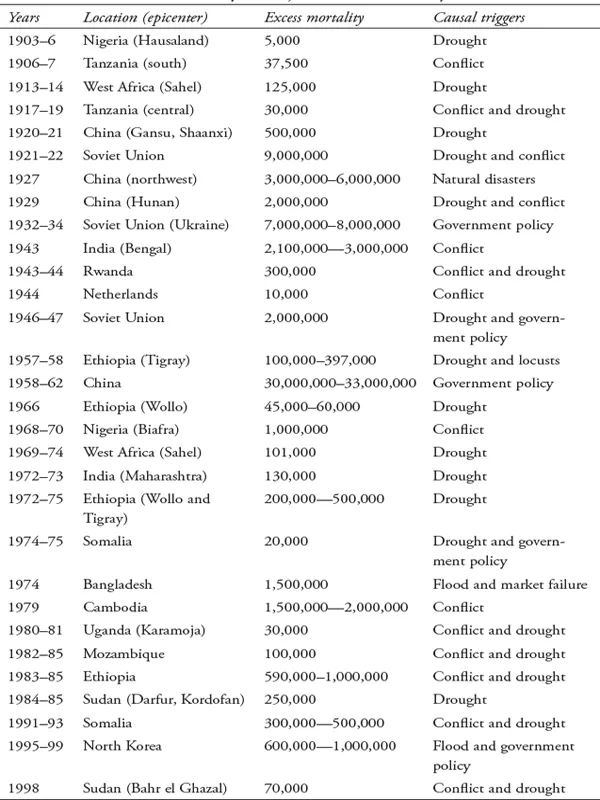

Famines and food shortages have been a perennial feature of the human condition and, as the North Korean case suggests, have by no means been eliminated. Table 1.1, adapted from Devereux (2000) with our estimates for the North Korean case, suggests that roughly seventy million people died of famine in the twentieth century.4 Yet a simple Malthusian picture of famine as a natural inevitability has become harder to sustain, because of changes both in the nature of famine and in our understanding of it. The postwar period has seen a gradual elimination of famine from virtually all parts of the world with the exception of Africa (North Korea, along with China and Cambodia, constitute important exceptions to this rule). One reason for this hopeful development is that famines caused by crop failure associated with natural disasters such as floods and droughts can be mitigated by the increasing ability of both the international community and national governments to respond to food shortages. Increasingly, famines and food shortages must be seen not as natural events but as complex man-made disasters. Civil conflict figures prominently in a large number of the famines listed in table 1.1, and, tellingly, the socialist famines—in the Soviet Union, Cambodia, China, Ethiopia, and North Korea—rank among the most deadly.

TABLE 1.1. Estimated Mortality in Major Twentieth-century Famines

Source: Adapted from Devereux 2000, table 1

In his early work on famine, Amartya Sen (1981) made the important observation that famine could occur even where aggregate supplies of food were adequate if there were failures in the distribution system, including through the market. Rather than focusing on the sheer quantity of food available, Sen’s analysis delved into issues of distribution and entitlement and in doing so set in train many of the most important debates on the phenomenon of famine that continue to this day. To what extent can famines in general, and any given famine in particular, be attributed to food availability decline as opposed to questions of distribution and entitlement? If we do find evidence of a decline in food availability, is this in fact a result of natural disasters, or must we also look at other causes, such as incentives for production or failure to access external sources of supply? And if we do witness entitlement failures—the inability of individuals to command the resources to gain access to food that is in principle available—to what political economy factors do we owe this failure?

Chapter 2 takes up these questions. We show that for military, political, and ideological reasons that can be traced to the division of the peninsula, the North Korean regime has consistently pursued the goal of achieving agricultural self-sufficiency. Whatever its political rationale, the economic logic for doing so is dubious; arable l...