![]()

1. U.S. PRINT CULTURE

THE FACTORY OF FRAGMENTS

Every thing is local.

—J. Hector St. John de Crévecoeur, Letters from an American Farmer, 1782

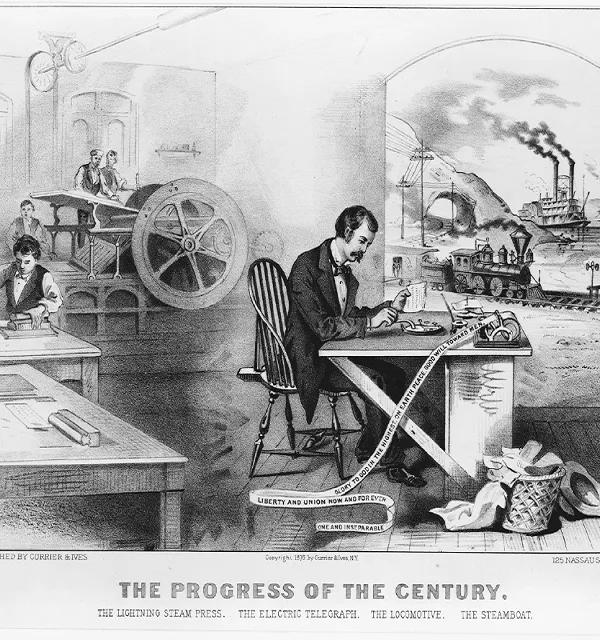

FIGURE 1.1 The Progress of the Century: The Lightning Steam Press, the Electric Telegraph, the Locomotive, [and] the Steamboat. New York: Currier & Ives, 1876. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-102264.

1. LOOKING BACKWARD: THE PRINT CULTURE THESIS

1876 was a year of epochal, periodizing fictions in the United States, marking for Americans the first national centennial, an astounding one hundred years of independence. In a commemorative print (fig. 1.1) titled “The Progress of the Century,” Currier and Ives celebrate this man-made event, evoking the grandeur of the unified state through the icons of the communications and transportation revolutions. The print tells its story in several distinct scenes of national improvement, arranged in raggedly clockwise manner. The result is a montage of American ingenuity that evolves from a barely noticeable gesture toward preindustrial production (a man working with his hands at the left margin of the frame) to ever more modern innovations as the viewer makes the visual rounds of the print’s circular composition. The story starts at nine o’clock with a residual artisanal figure lifting hammer and hand in an old-fashioned act of autonomous bookmaking. A few notches upward, at about ten o’clock, his handiwork has already been displaced by the cylindrical steam press that revolutionized printing in the 1830s, marking the definitive end of artisanal control of the book trade in the United States and the start of a more capitalized industry relying, as we see here, not on one hand but on a division of labor among many hands. Several notches past these three emergent Bartlebys, at about two o’clock, the print’s expansionist plot thickens with a battery of internal improvements, including canals, tunnels, steamboats, railroads, and a suggestive set of telegraph wires that leads us to the composition’s focal point: an isolated white-collar worker, looking quite tailored and Taylorized, who sits alone encoding a telegraph message into the Morse clicker while a pithy unionist epigram ticks off below him. As the historian Richard Brown has noted, the telegraph message serves as the picture’s motto, “join[ing] Daniel Webster’s 1830 unionist epigram” (“LIBERTY AND UNION NOW AND FOREVER ONE AND INSEPARABLE”) “with the universal message of Luke in the Bible” (“GLORY TO GOD IN THE HIGHEST, ON EARTH PEACE, GOOD WILL TOWARD MEN”) to suggest “that progress in communications promotes national union, piety, and peace.”1

The connection between national progress and technological innovation is a familiar one. But there are problems with the fictional unit of time this image labors to create. Despite the print’s epic title, the chief innovations depicted here do not represent the gradual evolution of American ingenuity but are instead specific technologies whose historical innovation dates to a narrower window in American history: the mid-1820s to the mid-1840s. The cylindrical steam press, for example, came into wide use only after 1825 and did not significantly impact American printing until 1833, with the rise of the penny press and the institution of large book factories like Harper and Brothers in New York; the steamboat likewise emerged in the 1820s, permanently altering the social and economic geography of the Northeast and West with the completion of the Erie Canal in 1825; railroads dominated expansion everywhere—but only after 1830; and the telegraph finally arrived in the 1840s to conquer utterly, as antebellum Americans liked to say, the national divides of time and space. By presenting these innovations within the unified space of the centennial picture frame, “The Progress of the Century” seems to suggest they were spread out over the course of one hundred years, in the process conflating the largely preindustrial moment of founding with its increasingly industrialized afterlife. Why are the technological innovations of two decades celebrated as the engines of an entire century? Like much nationalist rhetoric, this image represses the relative modernity of 1830s industrialism in a way that makes both the nation and its technologies of expansion seem to “loom” without rupture “out of an immemorial past.”2 This narrative in turn enacts an indispensable amnesia, insisting that these years were doing the work of unification in a way that conveniently covers over the skeleton in the national closet—that casket marked, in survey courses, “sectionalism” and “secession.”

This book tells a different story about the production of both printed texts and the American nation—a story that begins to take shape only when we note the specific origins of the technologies celebrated here. When we remember the emergence and proliferation of such technologies as historically specific events, we begin the work of contesting an official and retrospective narrative that casts technology as progress, nationally written. The dramatic industrial transformations of the 1830s, ’40s, and ’50s—so oddly telescoped in master narratives of American economic and literary history—provide ample opportunities to think about and theorize the ongoing processes of cultural integration (celebrated by historians as a “market revolution” and by literary scholars as an “American Renaissance”). But the timing of these transformations ought to point us in another direction as well: in short, toward the simultaneous experiences of disintegration and national fragmentation that mark these same years, in all their technological wonder.

Print culture lies at the center of this account because print is, without rival, American nationalism’s preferred techno-mythology. In local historical societies, rare book rooms, history classrooms, literature surveys, and PBS documentaries, print culture dominates America’s national narrative of how it began. But just as Currier and Ives telescope the industrial transformations of the 1830s to tell a story of triumphant union, so these text-based accounts of U.S. founding conveniently forget that there was no “national” print culture before the industrial revolution slowly centralized literary production in the 1830s, ’40s, and ’50s. Recognizing the material conditions under which a national print culture can and cannot function requires that we revisit and revise existing accounts of the relationship between print culture and nation formation. This book asks two questions in this regard: first, how do we account for nation formation in the material absence of a national print culture? And second, how do we account for the profound cultural fragmentation that accompanied the eventual emergence of national print networks between 1820 and 1860?

I argue that it was not the presence of a national print culture but the absence of one that ensured U.S. founding in 1776 and 1789. But even though no national print network existed at the moment of the American Revolution, that period still bequeathed to its heirs a profound belief in the possibilities of a more perfect, more material union—a union made increasingly “real” through the spread of post roads, canals, railroad tracks, and national periodicals that hailed an ever more reachable American public to recognize itself as a community in print. Cross-regional communication is, in fact, the fiction on which the founding based itself, and the antebellum period would serve as both the fulfillment of that founding fantasy and its undoing. Like some long-forgotten Rip Van Winkle, the United States finally wakes up after fifty years to find itself deeply entangled in the embrace of two contradictory developments—its own unionist rhetoric and an expanding regime of internal improvements that are meant to promote union and commerce but that actually only erode the one through the expansion of the other. After 1830, these newly awakened Americans must grapple with a national culture that is only just beginning to be made institutionally immanent as the many incompatible parts of the union are brought into increasingly uncomfortable alignment—an alignment visibly registered in and through the institutions of antebellum print culture.

Though one of the most identifiable agents of a wished-for and integrated national public, the printing industry not only was not celebrated in the 1830s for its role in the work of national consolidation but instead called forth scenes of deep division and dissent. It is no coincidence that the decade in which the technologies of steam and rail came into widespread use was also a decade that saw an astounding rise in mob violence against printers across the United States as well as the earliest threats of Southern secession and the ultimate entrenchment of stubborn sectional blocks. These developments were reinforced by the rise of the mass party system, which was in turn circularly reinforced by the rise of a mass media system—a system of interlinked antebellum newspapers that had an increasing capacity to share information both with each other and with distant subscribers in a reliable and timely fashion.3 Against the optimism of Currier and Ives—and I might add, much of our own retrospective optimism about the power of print to link dispersed citizens—I argue that this newly predictable set of connections did not create an ever-widening sense of imagined community so much as it disturbingly displaced one that was already rigidly in place. Indeed, the world of 1830s and ’40s print culture (and especially its ubiquitous periodical constituents—the newspaper, the magazine, the city directory, the trade annual, the gift book, and the almanac) called forth for antebellum Americans a new and destabilizing episode in the long history of what Benedict Anderson has called, in a more positive context, national “simultaneity.” For antebellum Americans, this sense of shared time and space was not a solution to the geographic displacement of one part of the population from the next; it was instead a new and frightening problem for those previously distinct and culturally autonomous populations. By focusing on the production of print networks and the circulation of actual objects within those networks, this book tracks the way that the textually imagined connections of 1776 and 1787 were eventually reified and then tested (after the nationalist fact) by more sustained, highly integrated systems of cross-regional contact. I take it for granted that such contact is largely produced by commerce but is ultimately figured, ideologically, by culture. What happens when the official national narrative of continental union, so entrenched in the nation’s local celebrations of itself, comes face to face with the material mechanisms that would seem to make it possible—canals, trains, telegraphs, and a thriving mass print culture? In the case of the early United States, the rhetoric that powered this proliferating infrastructure was an ever more literally understood “Union,” but the actual consequence was secession and civil war.

2. THE IMAGINED COMMUNITY AND THE ACTUAL ARCHIVE

One of the most compelling accounts of nationalism in the past thirty years has been Benedict Anderson’s Imagined Communities, and much of its well-deserved lure resides in its first word: imagined. Against the anti-nationalist pessimism that preceded him, Anderson eloquently described the role that desire, affect, creativity, and wishfulness play in the epochal world-building work of nations, states, and empires.4 But Imagined Communities also famously links the longevity and appeal of the nation as a form to the rise of capitalist networks more generally, describing nationalism as an affect that rides on the back of material objects. Anderson gives print pride of place among the many objects that circulate through these networks, arguing that the “territorial stretch” inhabited by New World populations “could be imagined as nations” only with “the arrival of print-capitalism” and that the sphere of circulation in which printed artifacts moved explains the territorial boundaries of particular nations (61). In this argument, print capitalism both registers a new comparative consciousness among different geographical populations and circulates the affect that attaches to such consciousness.

I would like to retheorize the relation of the “imagined” to the “material” in this argument by revisiting these interconnected claims, especially the question of whether networks of (print) exchange produce a circulatory and circulating field of affect. To this end, consider the case of a forgotten Enlightenment functionary named Hugh Finlay. Finlay was a British postal employee who, in 1772, was appointed by the Crown to inspect the King’s Post Road in North America.5 Traveling overland from his most recent post in Quebec, Finlay spent ten painstaking months between September 1773 and June 1774 surveying every postal office between Falmouth and Georgia, methodically recording everything he could find out about each road, bridge, horse, ferry, postal deputy, and rider on his route. Because the post road was the only inland material infrastructure that linked one colony to the next in the eighteenth century, Finlay’s journal represents one of our few comprehensive records of the material conditions attending the circulation not just of letters but of newspapers, pamphlets, novels, and every other imaginable printed (or tradable) object—things that could have moved from colony to colony only over sea by boat or over land by post road. The Journal thus offers nothing less than a material account of textual circulation on the eve of the American Revolution and in doing so allows us to test, on North American ground, some of Anderson’s central arguments about the ways that networks of exchange help to produce nations.

Finlay does, in fact, display a notable enthusiasm for translocal community, suggesting that dispersed collectivities were indeed being fantasized as connected entities via institutions like the post road. To this end, Finlay uses the Journal to propose (to himself) a series of postal improvements that might make greater use of the post road’s circulatory potential, advocating the wide distribution of “postal horns” to announce the arrival of new mail; the establishment of proper postal spaces (as opposed to the more customary use of private houses or public taverns); the introduction of new accounting methods; and sundry other “regulations” and “forms” (52). The Journal itself is a product of Finlay’s investment in such regulation: “written in a small, exceedingly neat, and perfectly legible hand” and later “bound in official vellum,” the journal never leaves Finlay’s possession (v). He carries it with him at all times because he hopes one day to use his notes to compute uniform distances for every rider in the king’s service. He expects to gather that document, in turn, into that most Enlightenment of orderly spaces—a printed book, a postal directory that will describe the movement of the mail in the most detailed, transparent, and organized way possible (90). Always empire’s creature, Finlay even suggests (to himself) that the service advertise his improvements in coffee houses throughout the empire in order to drum up more revenue for the king, from Wales to Savannah.

But Finlay’s Journal is a text divided between imagined communities and real ones. Finlay thinks of himself as one “whose business is to further the interest of the General Post Office, and facilitate correspondence by every possible means” (24). But seamless correspondence between colonial fragments was not only impossible in the early 1770s; it was in many ways undesirable to local populations who were deeply invested in a local autonomy they defined not only against England (or Canadian postal inspectors) but against each other as well. Finlay’s fantasies are thus not only highly bureaucratic; they prove unrealistic as well. Fin-lay may have earnestly believed in the post road as a highly functional network of exchange, but his administrative enthusiasm rarely met with success. The Journal thus unfolds as an unintentional picaresque, with Finlay recording his every movement in the hopes of producing a master administrative text for empire and for king—even as that goal, like Fin-lay himself, is comically resisted in every colonial nook it enters. Indeed, much of the Journal’s comic appeal derives from the fact that Finlay never sees what every reader must: the utter impracticability of his desire to organize and control the provincial mails against the combined forces of custom, weather, and technological impediment. The chaotic forces of disorganization appear on almost every page of the Journal. Not only are the roads bad and the postal riders cunningly resistant to regulation, but there are no inns for Finlay when he needs rest and often no horses to transport him when he needs to move. Some customers are too “indigent” to pay for their mail, while their neighborly postmasters are too kind not to deliver it (16). In some places, mail is routinely delayed while printers set its content in type for local news gazettes (31). Some riders are known to ride drunk (55); others carry letters “privately,” burdening their horses with extra packages the king is never compensated for. As one deputy tells Finlay, “there’s two post offices in New Port, the King’s and Mumfords, and … the revenue of the last is the greatest” (32).

This last problem might suggest that the problems Finlay faces are proto-Revolutionary ones (with incipient Americans—like Mumford—resisting the king’s entitlement). But even in loyalist colonies, Finlay’s elaborate plans are pragmatically foiled by any number of local problems—from bad roads to lost papers. He often arrives to find offices whose accounts have gone unsettled for decades—if ever settled at all: in one, the postmaster has died, leaving no records behind (63); in another, the postmaster “says he cannot settle … because his children and negroes in his absence from home got into his office and destroy’d his Papers” (58); a third postmaster absconds to the West Indies, taking the king’s profits with him (89, 92); while a fourth has moved to another colony and taken up a new profession (89, 92). Those who have kept records, on the other hand, have struggled for decades with severe paper shortages, keeping their accounts on “scrap[s]” of which nobody can now make sense (83).

The post office is, in short, a mess, and Finlay’s figure for this cacophony is the postal rider’s “portmanteau.” The box or bag in which official mail was, by law, to be locked, the portmanteau is one thing in theory but quite another in practice:

The Portmanteaus seldom come locked: the consequence is that the riders stuff them with bundles of shoes, stockings, canisters, money or any thing they can get to carry, which tears the Portmanteaus, and rubs the letters to pieces. [One rider’s] Portmanteau was not lock’d; it was stuff’d with bundles of different kinds, and cr...