![]()

PART ONE

![]()

INTRODUCTION

Then she said, “I will teach you to read ifranji [French].” And I became her pupil, and she began honoring my companions. Love [mahabba] grew between us so much that I was distraught by it and I said, “Before meeting her, I was at odds with the Christians, and engaged in the holy fight for religion. But now, I am at odds with myself and Satan.”1

Ahmad ibn Qasim was an Andalusian Morisco who fled from Spain in 1597 and settled, like many of his compatriots, in Morocco. He was proficient in Spanish and, to the surprise of his wary coreligionists in Morocco, Arabic too. Sometime in early 1611, he was sent with five other Moroccans by the ruler Mulay Zaydan to France and the Netherlands on a mission to retrieve goods that had been stolen from Moroccan ships—or to demand compensation for them. During his three-year stay in these two countries, he observed and reflected on the nasara/Christians among whom he was staying, debated and argued, feasted and prayed, made friends and enemies. Much as he was inimical to “infidel” Europeans who, knowing little about Islam, did not hesitate to denounce it, he still sought engagement with Christian men and women, scholars and princes, and developed complex relations, even love, with them.

The history of Arab-European relations began with the advent of Islam and its expansion into North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula (A.D. 711), and, in the East, with the early Abbasid attempts to conquer Constantinople, and the final victory of the Ottomans over the Byzantine capital in 1453. By that year, Arab writers had become quite familiar with the Europeans, both as Crusaders and as geographical neighbors.2 From Istanbul, the Ottomans began pushing into Central and Western Europe until the failed attempt against Vienna in 1683; at the same time, the Western Mediterranean/the Maghrib became a theater of coastal invasions, piracies, and abductions—what Fernand Braudel called the “small wars” between Christendom and Dar al-Islam. In all these regions and times, the Arabs, the Berbers, the Turks, the Ottomans, and other Muslims as well as Eastern Christians came into contact with European Christians. Although warfare often dominated these contacts, there were various venues of interaction that were not confrontational, especially after frontiers stabilized and trade, diplomatic exchange, commerce, and political alliance flourished. Muslims recruited Christian mercenaries to fight in their wars, as Christian rulers had earlier relied on Muslim physicians and military personnel to help them in times of need. From Marrakesh to Alexandria and from Santa Cruz/Aghadir to Istanbul, Europeans settled and conducted business at the same time that Muslims adopted innovations and material culture from the Europeans whom they visited, kidnapped, or were kidnapped by, and, as in the case of Ahmad ibn Qasim, loved.

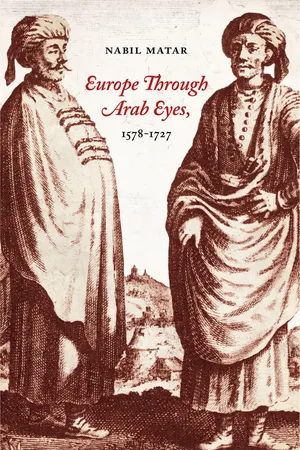

It is this familiarity between the two religious societies of Arabic-speaking Magharibi and Western Europeans that this book will explore—the Arabic image of the nasara of Europe between 1578 and 1727.3 The starting date for this study is the year that witnessed the victory of Wadi al-Makhazin/Alcazar (al-ghazwa al-ʿuzma/the Great Raid, as Moroccan historians remembered it) and the accession of Mulay Ahmad al-Mansur to the throne in Marrakesh. The Moroccan victory over the Portuguese-led crusade in 1578 marked the beginning of the Muslim reconquista of regions in North Africa formerly colonized by Europeans, a reconquista that continued for more than a century and succeeded in liberating most, but not all, of the Spanish, French, and British outposts. (Today, Spanish Ceuta and Melilla are reminders of the age of European empire.) The ending year is the date of the death of the Moroccan ruler Mulay Ismaʿil (and of George I and close to the death of the Ottoman sultan Ahmed III, in 1730). It concluded the rule of a powerful Magharibi leader whose influence was felt throughout the Western Mediterranean, both Christian and Muslim.

This period, 1578–1727, has been ignored by historians of Arabic and Islamic civilizations who have turned their attention either to the study of the medieval period, with its numerous geographical texts and travelogues about the lands of the Christians, or to the modern period, with its Middle Eastern nahda/Renaissance and its appropriation of European social and political ideas. While the medieval period resonated with Islamic power, the modern period rebounds with the devastating impact of European imperialism on the Arab and Muslim worlds. In both periods, there was an imbalance that resulted in stereotypes of otherness, and—chiefly from the Western legacy—a thriving and triumphant orientalism. In the early modern period, however,4 and in the Arab-Islamic West, there was less of a monolithic construction of otherness and more of a diversity of perspectives—an evolution of responses and reactions toward Christendom based on changes in geopolitical relations. The study of the early modern period is important because it redirects today’s East-West and colonized-colonizer discourse to the specificity of historical antecedents. By going behind the binaries created by European imperialism after the eighteenth century, historians gain access to an Arabic historiography that was both complex and not—not yet, at least—essentialized, a historiography that had been epistemologically molded by the ongoing engagements and encounters with the European nasara.

The “Arabic” that will be discussed in this book will be chiefly the Arab-Islamic West: Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia (the triple Maghrib), and Libya, although some attention will be paid to the Mashriq Levant too. The reason for the Magharibi emphasis is the distinctive culture that prevailed in that region, dictated by its geographic proximity to Europe and its changing demography after the arrival of hundreds of thousands of expelled European/Christianized Muslims, the Moriscos, throughout the sixteenth century, culminating in the exodus of 1609–1614. Even European writers of the time recognized the uniqueness of the “Western Mussulman” or “Western Moors.”5 Although all Muslim writers about Christendom were convinced that they possessed absolute religious truth and therefore were not dissimilar from each other in their sense of superiority to the Christians, the separation of Morocco from the Ottoman Empire and the Arabic linguistic continuity and cultural autonomy that persisted in the North African regencies produced a Magharibi interest in, and reaction to, Europe that was quite different from that of the rest of the Islamic world.6 It was in the Maghrib that a triangulation of encounters took place in the early modern period: Moroccan/Magharibi—Ottoman Turkish—Euro-Christian (Protestant British and Dutch, and Catholic French and Spanish, Italian and Maltese). It was the misfortune of the Islamic West that its study was completely subsumed under the Ottoman Empire in Fernand Braudel’s magisterial The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II. But Europe was more frequently encountered in the Islamic West, and quite differently, than in the Ottoman Levant.7 As the contrast between contemporary travelers to Christendom will show (chapter II)—one from the Mashriq and the other from the Maghrib—there were important cultural and ideological priorities that dictated the differences in perception and reaction.

A SURVEY OF THE LITERATURE

Historians of the medieval period have argued that Muslim Arabs and non-Arabs (but writing in Arabic) did not show interest in Latin Christendom as they did in the Far East, since no comprehensive surveys of medieval Christendom have survived as they have about China and India. In his seminal work, Al-ʿArab wa-l Barabira (1991), ʿAzīz al-ʿAzmeh explained that medieval Arabic travel and geographical authors treated the Europeans as barbarians of little interest: because Europeans were Christian, and since Muslims approached Christianity through the prism of the Qur’an, Muslims did not bother to study European society; in their view, that society was summed up in its theology, which was, according to the Qur’an, false and distorted. As a result, the Arabic interest turned toward the East, with its ancient civilizations and vast intellectual output, which, as of the eighth century, played a significant role in the formation of Arab civilization.8

Tarif Khalidi contested al-ʿAzmeh’s position by exploring the Muslim geographical, historical, and cultural views about Western Europe in the Classical Period.9 As far back as al-Masʿūdi (d. 956), the Baghdad-born traveler, Khalidi argued, there had been writings about the Greeks and the kings of the Franks, and about the scientific legacy of these peoples, although not about their political history or geography.10 Khalid Ziyadah returned to al-ʿAzmeh’s position, arguing that from the Crusades on, Western Europeans became more informed about Dar al-Islam than Muslims did about Christendom.11 Only a few medieval Muslims wandered into Western or Central Europe and wrote about it: al-Ghazal in the ninth century12 and Ibn Fadlan in the tenth13 are famous for having left behind descriptions of Denmark and eastern Russia, respectively. Ibn Khaldūn (d. 1406) wrote about the Greeks and the Latins, praising their civilizations, being the only medieval Muslim historiographer to use Latin sources in his exposition.14 Although he noted the growing power of the Christian nations of Europe, and the progress of their technologies and innovations, his information about those nations remained limited, because his travels, like those of his famous predecessor from Morocco, Ibn Battuta (d. 1369), had taken him eastward rather than northward (although earlier in his life he had gone to Spain, about which he wrote only a few lines).15 In Byzantium Viewed by the Arabs, Nadia Maria El Cheikh (2004) carefully showed the range of accurate and inaccurate images that the Arabs had of the rūm/Byzantine Christians from the first allusions in the Qur’an (ca. 610–632) to the fall of Constantinople in 1453. El Cheikh examined a wide range of sources from literature, history, theology, and travel writing, demonstrating how Arabs possessed both stereotypical and empirically derived information about the formidable adversary to their west. In ʿAlam al-Qurūn al-Wusta fī Aʿyun al-Muslimīn/The World of the Middle Ages in Muslim Eyes (2007), ʿAbdallah Ibrahīm dedicated the second unit of the book to the “North”/Europe, with selections from authors ranging from Abu al-Fida’ to al-Masʿūdi and from Ibn Rustah to al-Tartūshi, al-Ghazal, and Usamah ibn Munqidh.

ʿAzīz al-ʿAzmeh reentered the debate by turning scholarly attention to the Muslim West and arguing that when the Muslims were in cheek-by-jowl proximity with the Christians in the Iberian Peninsula (before 1492), their discourse about the Christian adversary was derived not from their actual contact with them but from poetical and literary stereotypes. The images were uniformly denigrating, ranging from descriptions of Christian men as descendants of drunkards and uncircumcised pig breeders to characterizations of Christian women as lascivious and voracious.16 While al-ʿAzmeh’s evidence is compelling, his thesis does not apply later: the fall of Granada in 1492 and the beginning of the final expulsion of the Moriscos from Spain in 1609 brought about a complete separation between the two sides of the Mediterranean during which time Magharibi writers neither emulated their stereotype-bound predecessors nor employed the intellectual paradigms and technological tools of “Occidentiosis” (to use Edward Said’s term). Instead, they relied on their actual experiences of engagement and encounter, producing information about the Europeans that was empirical and specific. As Bernard Lewis noted, “The main movement of refugees” in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries was from Europe to the Levant17 (and North Africa). Such movement inevitably facilitated the transfer of information about the Europeans to the Arabs and the Muslims.

In Trickster Traveler, Natalie Zemon Davis offered an insightful study of the life and writings of Hasan al-Wazzan/Leo Africanus and of Christian-Islamic relations in the late medieval Mediterranean. At the end of her introduction, Davis asked an important question: “Did the Mediterranean waters not only divide north from south, believer from infidel, but also link them through similar strategies of dissimulation, performance, translation, and the quest for peaceful enlightenment?”18 She then turned to answer the question by situating the writings of al-Wazzan in the context of earlier and contemporary Arabic and Italian literature and culture.19 As her study demonstrates, al-Wazzan presented in his famous account about North Africa a cautious view of Christians and Christendom, but one that was informed by tolerant breadth toward all the Jews and the Christians whom he met. Because the text was written in Italian, however, it did not have an impact on the Arabic-speaking region (its first translation into Arabic took place in the last quarter of the twentieth century). Western Arabic authors coming after al-Wazzan diverged from his breadth, because by the end of the sixteenth century the “infidels” had occupied far more regions in North Africa than al-Wazzan could have imagined possible. Just over half a century after al-Wazzan’s death, the Moroccan ambassador, al-Tamjruti, sailing the same route that al-Wazzan had, expressed antipathy to the Euro-Christians, “may God destroy them,” whose military and naval expansion had become aggressive and destructive (see translation #3).

Andrew C. Hess’s The Forgotten Frontier: A History of the 16th-Century Ibero-African Frontier (1978) confirmed that in the sixteenth century, the Mediterranean, which had been a location for intellectual and cultura...