![]()

1. FOUR MEN

PAR·NAS·SUS (pär-năs‘əs) also Par·nas·sós (-nä-sôs‘): A mountain, about 2,458 m high, in central Greece north of the Gulf of Corinth. In ancient times it was sacred to Apollo, Dionysus, and the Muses. The Delphic Oracle was at the foot of the mountain. Metaphorically, the name “Parnassus” in literature typically refers to its distinction as the home of poetry, literature, and learning.

PARNASSUS IS a commonly accepted metaphor for the ultimate recognition of literary, musical, or intellectual achievement. Arrival on this exalted peak demonstrates that the process of canonization is complete. In the final analysis, the underlying theme in the following conversational quintet is an examination of the desire for canonization and the process whereby it is achieved. Among my four protagonists, solely Walter Benjamin—now considered to be one of the most important and influential philosophers and socioliterary critics of the twentieth century—ascended Parnassus posthumously. The other three had reached Parnassus while still alive. At the time of his suicide in 1940, only a limited circle of predominantly German intellectuals—among them Theodor Adorno, Hannah Arendt, Bertolt Brecht, and Gershom Scholem—considered Benjamin of Parnassian stature. The content and style of his writings was so complicated, even convoluted; the range of his interests so wide; and his publications so fragmented, that only a limited circle of contemporaries and especially recipients of his letters and reprints were able to absorb and appreciate the extraordinary depth and breadth of this powerful thinker. To paraphrase Hannah Arendt, “for fame the opinion of a few is not enough.” Only in the 1950s as his writings started to be collected and published under the editorship of Adorno, his wife Gretel, and of Scholem did Benjamin receive recognition in Europe. In America the pivotal event was the publication of the English translation in 1968 of Hannah Arendt’s collection of Benjamin’s most famous essays under the title Illuminations, at which time Walter Benjamin was already ensconced on Parnassus. But as Arendt states in her introduction to Illuminations, “Posthumous fame is too odd a thing to be blamed upon the blindness of the world or the corruption of a literary milieu.” Timing also has to be right and the post-Nazi, Marxist dialectics climate of the 1960s culminating in the student movements of 1968 was ideal.

There are certain rules and conditions that I have invented for the Parnassus where my four protagonists are finally meeting once more. Benjamin had asked his two friends, Adorno and Scholem, to meet him for an elucidation of some missing facts, because in my postmodern Parnassus everything that happened during a person’s lifetime and since arrival on Parnassus is known; in fact, Internet access or Amazon-type ordering of current books is also possible, but no e-mail contact with the outside world nor any new creative work. So what is Benjamin’s problem? Since he alone arrived posthumously on Parnassus, there is a gap in his autobiographical knowledge between his suicide in September 1940 and his arrival on Parnassus some two decades later. Could they help him fill that gap?

In the many hundreds of books and thousands of articles, the trio Benjamin, Adorno, and Scholem frequently occurs together. But what about the presence of the fourth, Arnold Schönberg? There is no evidence that either Benjamin or Scholem ever met the composer. In fact, not even Benjamin’s writing shows any affinity to or interest in Schönberg, although I now describe a hitherto unknown, distant, factual familial relationship. Adorno, on the other hand, had a lifelong connection with Schönberg. Still in his early twenties, after a precocious doctoral thesis in philosophy, Adorno went in 1925 to Vienna to study composition with Schönberg, although his actual teacher was Alban Berg. For years, they had a respectful yet contentious relationship,1 which underwent its severest test when Schönberg blamed Adorno for misrepresenting his persona when advising Thomas Mann for the development of the key figure, the twelve-tone composer Adrian Leverkühn, in his novel Dr. Faustus. Eventually, Schönberg forgave Mann, but not Adorno.

But that is not the reason why I have included Schönberg along with the trio. I needed him as an important foil as well as participant in chapters 2, 3, and 4, because the canonization process that reoccurs in all these chapters refers not only to persons but also to works of art, including music. Arnold Schönberg had invented a four-party chess game, coalition chess (Bündnisschach). The basic rules of the game are as follows. Two of the four players have twelve chess figures (yellow and black) at their disposal and are thus considered the two “big” powers, whereas the other two have only six figures (green and red), thus representing the “small” powers. After the first three moves, two “coalitions” ensue in that one of the small powers declares itself associated with one of the big ones. Thereafter the play continues until checkmate is reached.

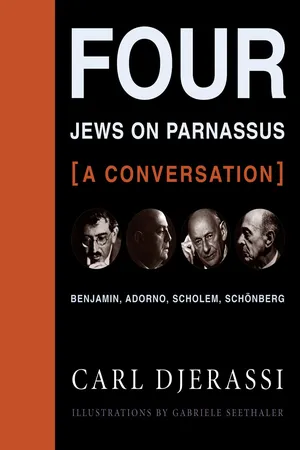

Since the conversational confrontations of my protagonists can almost be considered an array of social chess gambits involving both attack-defense as well as collaborative moves, Gabriele Seethaler has introduced visual alterations of Schönberg’s coalition chess as the leitmotiv for the five chapters—itself an attractive photorealistic gambit.

And now, meet my four characters, before we turn to their wives.

The sound of Max Bruch’s “Kol Nidrei”2 is heard for thirty to sixty seconds, starting with the full sound of the cello, as Arnold Schönberg and Theodor W. Adorno listen.

SCHÖNBERG: Stop! (The music stops abruptly.) Today is Yom Kippur … the Day of Atonement when Kol Nidre is played. But why always Max Bruch’s? At least up here, on Parnassus, let’s hear my version for a change. Without the cello sentimentality of the Bruch. Kol Nidre needs words … not just music!

1.1. Gabriele Seethaler, Walter Benjamin, Theodor W. Adorno, Gershom Scholem, and Arnold Schönberg on Parnassus Inserted Into Arnold Schönberg’s Coalition Chess.

(Schönberg’s Kol Nidre [Opus 39]3 is heard through the musical introduction and the start of ...