![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Origins of Crypto-Judaism on the Iberian Peninsula, 200 B.C.E.–1492

The roots of Jewish settlement penetrate deeply into the history of the Iberian Peninsula. While legend placed Jews in Spain as early as the sixth century B.C.E., after the destruction of the First Temple by Nebuchadnezzar, more solid accounts trace their residence on the peninsula to the Diaspora, which occurred during the time of the Roman Empire, beginning in the second century B.C.E. At this time, Jews, exiled from their ancestral homeland, found themselves scattered across the Mediterranean region, including the southern and eastern coasts of Spain, where they established bases from which they engaged in commerce within Phoenician and Syrian trading networks. Under the administration of the Romans, Spanish Jews enjoyed centuries of relative peace and toleration. After the conversion of the empire to Christianity, however, the situation of the Jews began to erode.1

Conflict between Jews and the nascent Christian community began to appear in the early fifth century, when the bishop of Mallorca embarked on a campaign to convert the prosperous Jewish settlement on the island of Menorca.2 Historian Jane S. Gerber wrote of the “inevitable” confrontation between the two faiths in Spain:

Christianity defined itself as the successor to its older (and, as is often said, rival) sibling in the divine drama. . . .

Church thinkers could not simply dismiss Judaism out of hand. Their most troubling challenge was the enigmatic perseverance of the Jewish people after the advent of Jesus had made their religion obsolete. . . .

A fateful rationale was devised from the doctrine of Christian supersession: the Jews would be preserved because their veneration of the Old Testament bore witness to the truth of Christianity. At the same time, they would be tolerated only minimally, so that their debased state itself would provide visible proof of their “rejection” by God.

The paradoxes of a doctrine that simultaneously advocated toleration and discrimination, preservation and persecution, conversion and persuasion, would plague Jews for centuries.3

Indeed, from the fifth through the seventeenth century, Jews and, later, crypto-Jews were to suffer greatly from this contradictory policy on the part of the Church, which would eventually come to define Judaism as la ley muerta de Moisés, or “the Dead Law of Moses.” Over time, Jews would develop strategies for survival, ranging from accommodation to flight to conversion.

EARLY CONFLICTS BETWEEN CHRISTIANS AND JEWS

In the mid-fifth century, the Iberian Peninsula was invaded by successive waves of Germanic bands, the last of which were the Visigoths, who succeeded in driving the others out of the land. The Visigoths practiced Christianity, but maintained significant doctrinal differences from the approximately 8 million Spanish Catholics who fell under their domination. As long as these tensions between Visigoths and Catholics remained in effect, the rulers found the Jews useful as mediators or allies, depending on the exigencies of the day.4

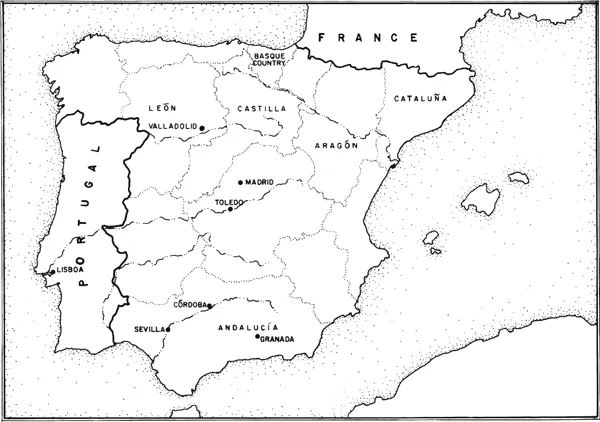

Under the Visigoths, patterns of economic life began to emerge among Spanish Jews that would change little for centuries to come. Concentrated for the most part in the towns in the regions of Cataluña and Andalucía, and in the city of Toledo, they held government and military positions; engaged in commerce, both domestic and foreign; and administered the estates of Christian nobles. Some Jews owned land, either farming it themselves or utilizing the services of slave labor. Relations between Jews and the ruling Visigoths were by no means harmonious, especially after their conversion to Catholicism at the end of the sixth century. Codes were enacted that severely restricted the opportunity for Jews to hold office, intermarry, and build synagogues. Increasingly through the sixth and seventh centuries, zealous Visigothic kings sought the conversion of Spanish Jews. Through a combination of positive and negative incentives, they were moderately, although by no means totally, successful in achieving their end. Those who retained their faith, like their descendants who were also forced to pursue their religious beliefs in a hostile environment, tended to observe such basic rituals as sanctification of the Sabbath and festivals, dietary laws, and circumcision.5

THE “GOLDEN AGE” OF SPANISH JEWRY UNDER MUSLIM RULE

With the invasion of the Iberian Peninsula by Muslims in 711, Spanish Jews received a reprieve from persecutions and attempts at forced conversions. While the Muslims by no means pursued a policy of total religious freedom, the general atmosphere was one of toleration of non-Muslim practices. Barriers to social and economic mobility, imposed earlier by the Visigoths, were by and large removed. Jewish communities in areas under Arab rule, and eventually in Christian areas as well, were allowed a large degree of autonomy in the administration of their own affairs.6

Moreover, Jewish influence manifested itself in the upper echelons of Muslim economy and society, with Jews serving as influential physicians, financial advisers, and ambassadors to the caliphs. Historians have referred to this period as the Golden Age of Spanish Jewry, represented by a fluorescence in almost every aspect of Jewish culture. The era was characterized by such government leaders as Hasdai ibn Shaprut (915–970), literary figures as Yehuda ha-Levi (1075–1141), and philosophers as Bahya ben Joseph ibn Pakuda (ca. 1050–ca. 1100) and, most celebrated of all, the theologian/philosopher Moshe ben Maimon, better known as Maimonides (1135–1204), who still stands as one of the most important spiritual writers in Jewish history.7

Geographically, Jewish settlement expanded throughout the Iberian Peninsula, initially to the major cities in Andalucía, Córdoba, Sevilla, and Granada, and eventually, through the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, to the more heavily populated Christian regions of Castilla, León, and Aragón. During the Muslim and early Christian periods, Jews tended to pursue urban trades—as artisans and shopkeepers—in addition to serving as tax farmers for Christian nobles. This latter function earned the enmity of their poorer, more rural Christian neighbors.8

CONVIVENCIA AND CONVERSION

The hostility directed against the Jews of Spain by the Christian populace, nurtured by generations of civil war and taxes, in many ways represented a continuation of the anti-Jewish sentiment from the time of Visigothic rule. The new phase began in the eighth century, with the inception of the reconquista, the attempt on the part of Christian leaders to reconquer the Iberian Peninsula from the Muslims. Over the course of the eight-hundred-year reconquista, this effort became more than just a campaign to defeat the Muslim armies, more than just an attempt to expand the realm of the monarchs of Spain. Rather, it became a veritable crusade against what the Christians regarded as the “infidel,” a term that was directed largely against the Muslims, but included the Jews as well.

Despite the hostilities that often plagued the period of the reconquista, which pitted Christians against Muslims, with Jews alternatively supporting one side or the other and serving as intermediaries between the two, there occurred long intervals of peaceful accommodation among the three ethnic groups, periods that historians have labeled the convivencia (time of coexistence). In the reconquered areas under the control of Christian rulers, Jews played roles similar to those they had under the Muslims, as municipal officials, merchants, financial advisers, tax collectors, and military officers.9

In the process of pursuing its conversion efforts through the thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth centuries, the Church utilized peaceful as well as violent means. The more idealistic members of the Church hierarchy sought to win Jewish converts through a prolonged series of debates, or disputations, which pitted theological scholars of both faiths against each other in an attempt to persuade Jews to convert or dissuade them from doing so. The Churchmen aimed their arguments at the Jewish population at large, rather than at the rabbis. They attempted to “instruct,” rather than debate, citing Talmudic as well as New Testament sources to prove the absolute truth of their position.10

But as the anti-Jewish sentiment that was sweeping through Europe filtered southward into Spain through the mid- and late fourteenth century, conversion efforts on the part of the Church turned increasingly violent. Jews were held responsible for a host of crimes, ranging from poisoning wells to using the blood of Christian children in Passover rites to causing the Black Death. Seizing the opportunity to capitalize on popular antagonism against the Jews, Father Ferrán Martínez in the late 1370s initiated a campaign designed to destroy the Jewish community in Sevilla. Violence broke out in Sevilla in the summer of 1391 and spread northward and eastward to Castilla and Aragón, forcing the residents of the juderías throughout Spain to either convert or face death. Approximately 100,000 Jews converted at the point of a sword. Another 100,000 refused to convert and were killed, while another 100,000 escaped.11

Whether forced or “gentle,” the conversion effort on the part of the Church achieved a high degree of success, especially among those wealthier and better educated members of the Jewish communities. How “Jewish” or “Christian” were the conversos? Most historians of the period believe that, generally, the transition from Judaism to Christianity was made without a great deal of inner spiritual conflict, for it represented a change of religion in name only. The bulk of conversos and their offspring did not take their new faith seriously. Many conversos continued to participate in the social, political, and religious affairs of their synagogues.

Yitzhak Baer articulated the strong ties of the conversos to their ancestral faith through the early to mid-fifteenth century:

Not only did actual converts (anusim) try with all their might to live as Jews, but even the children and grandchildren of apostates who had forsaken Judaism of their own free will and choice were now inclined to retrace their steps. The conversos secretly visited their Jewish brethren in order to join them in celebrating the Jewish festivals, attended the synagogues, listened to sermons, and discussed points of religion. They did no work on the Sabbath, observed the laws of mourning and the dietary laws, and fasted on Yom Kippur and even women observed the Fast of Esther. They had Jewish prayer books and engaged their own Hebrew teachers and ritual slaughterers. They sent oil to the synagogue for the lamps and were provided by their Jewish brethren with literature that lent them courage to hope for consolation and redemption in days to come.12

One of Baer’s students, Haim Beinart, who went on to distinguish himself as the dean of Iberian Jewish history, also recognized the strong devotion of a large number of conversos to Judaism:

Their very existence as Jews brought the conversos to regret their adherence to Christianity in a moment of weakness and their separation from the Jewish people. The many Inquisition files that have come down to us cover merely a fraction of the people investigated by the Inquisition. They testify to the desire of the conversos and their descendants, even after generations of living as Christians, to return to their people and their Jewish past. . . . The existence of the Inquisition over hundreds of years and its unrelenting effort to excise the conversos who had returned to Judaism are prime proof of the failure of the entire system in its war against Judaism.13

Maintaining a view diametrically opposed to the mainstream historiography, Benzion Netanyahu disputed the notion that a significant number of conversos continued to practice their ancestral Jewish faith in secret, especially in the generation following the pogroms of 1391. Rather, he asserted, the children of these conversos were “born and reared in the Catholic faith and lived according to Catholic law.” Moreover, he continued, with regard to those Jews who converted voluntarily through the mid-fifteenth century, “there was no reason to assume that a large number of [these] conversos lived secretly as Jews or lacked devotion to the Catholic faith.”14 Netanyahu rejected the validity of Inquisition records and other Christian sources that documented the alleged secret practices of Judaism on the part of New Christians. He confessed that he was

baffled by the great credence given by historians to those documents and to the claims made by the Inquisition on their basis. Little value, I thought could be attached to ev...