![]()

There should be understanding before there is hope.

—Ra’anan Alexandrowicz

1

Collision Course

An Expanding Appetite for Resources Coupled with Population Growth on a Finite Planet

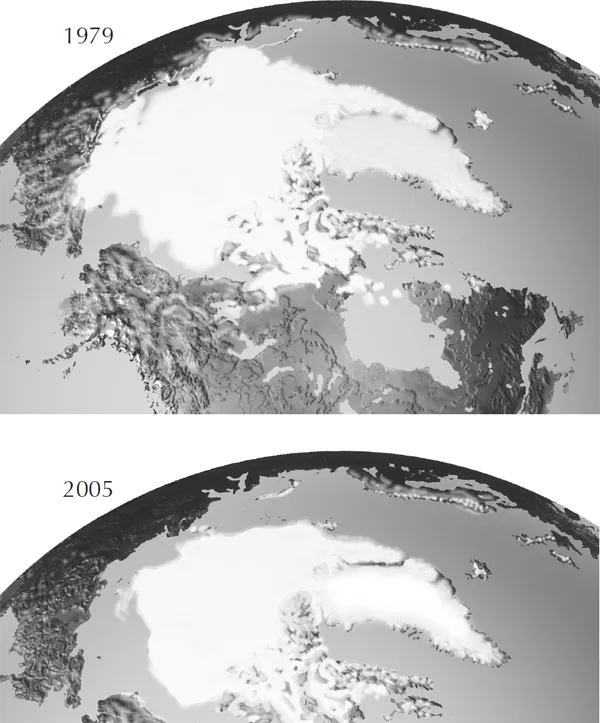

Power, wealth, and security are inextricably linked to what our Earth provides us and how we treat the planet that sustains us. In the sixteenth century, power and wealth revolved around trade, with the nations of Europe (the global superpowers of the day) racing to establish reliable and quick trade routes with India, China, and Japan. The search for the Northwest Passage to circumvent South America and sail directly to Asia began in the early sixteenth century and continued until the beginning of the twentieth, when, in 1906, Roald Amundsen, the famous Norwegian explorer, sailed a dangerous, iceberg-cluttered route from Norway to what is now Alaska. But that route was too hazardous and shallow to be used as a trade route, and it was not until the 1950s that a medium-size icebreaker navigated the Arctic Ocean north of Canada. In the past few years, our climate has warmed so much that now, during summer, the Arctic ice sheet melts and commercial vessels are finally able to traverse the Northwest Passage (figure 1.1). By the summer of 2007, the ice sheet had melted to about half the size it was 25 years earlier.

We can only imagine how history would have changed if the climate had been warm enough in the sixteenth century to allow free passage north from North America to India. Would Canada be more wealthy and powerful than the United States? Would Britain have focused even more attention on Canada? Would the French have been willing to offer the Louisiana Purchase? Today’s questions are similar: Given current trends, will polar bears go extinct if polar ice sheets continue to diminish? Will native Inuit (Eskimos) or other Arctic indigenous people maintain any semblance of their traditional ways? Will the balance of power among Earth’s nations shift in response to global climate change? Global climate has clear and strong effects on human affairs and the natural world.

FIGURE 1.1 The Arctic ice cap in (top) summer 1979 and (bottom) 2005. The ice cap along the lower left side (above Alaska) has retreated about 400 miles (650 km). (Images courtesy of NASA)

A fire from the burning remains of slashed rainforest so large it can be seen from space, sheets of ice the size of small countries breaking off Antarctica, fish in remote Arctic lakes too contaminated with toxic chemicals to be safely eaten, and precipitous declines of every major ocean fishery—these are just a few signs of the pervasive influence of humans on our world. Plastic waste from humans can be found in every ocean and on every beach on Earth.1 Global impacts of humans on their environment, such as the greenhouse effect and increases in ultraviolet radiation caused by ozone depletion, are reality.

I define “environment” in this book as physical, chemical, and biotic features that affect organisms, including humans, and determine their survival and the resources available to them. Humanity’s footprint (the sum of our environmental impact) has likely surpassed the capacity of Earth’s environment to sustain our actions, and our global impacts continue to increase.2

Bill McKibben, who has written extensively about environmental issues, has referred to pervasive human impacts as “the end of nature.”3 By this he means that wild nature, unaffected by man, no longer exists. Human influences extend to the most remote regions on Earth. Pesticides are found in animals in the open ocean and far north in the Arctic, areas far from human habitation. As we continue to alter global climate, no ecosystem will remain uninfluenced. Changes will be profound, long lasting, and pervasive.

Humans are moving forward into a global environmental future with tremendous momentum. Momentum is what makes a runaway train so dangerous; even immediate application of the brakes does not stop the train for many miles. Our environmental momentum may have already overshot the capacity of Earth to support us. This environmental momentum occurs as a result of the magnitude of global processes and because humans are accelerating numerous global trends. Many trends, fundamentally driven by increases in global population and the amount and efficiency of resource use, are influenced by the enormity of this momentum. I try in this book to define the trajectory of the missile fired by the environmental catapult (where humanity is going), the momentum of our global environmental impact, and our ability to control the trajectory in the face of the tremendous momentum.

More than 6.5 billion people currently live on Earth. People use the energy equivalent of more than 33 billion U.S. tons (30 billion metric tons) of oil each year. The global economy (annual global domestic product) has reached more than $25 trillion. How many is 6.5 billion people, how much is 33 billion tons of oil, and how much is $25 trillion? If a particular special person is one in a million, there are currently over 6500 special people just like them in the world. Picture a stadium that holds 50,000 people. Two stadiums would hold 100,000 people; 20 would hold 1 million; 20,000 would hold 1 billion; and 130,000 would be needed to hold all the people on Earth. I have difficulty conceiving of 130,000 stadiums, let alone 130,000 stadiums with 50,000 people in each.

Assuming that a large stadium can hold a volume of 110 million cubic feet (3.1 million m3) of liquid, the approximate capacity of the Cleveland Browns’ football stadium, the volume of oil required to provide the equivalent of energy used by people on Earth each year would fill more than 11,000 such stadiums. Stacking 1 million $1 bills, each 0.0043 inch (0.1 mm) thick, would result in a stack 358 feet (109 m) tall. A stack of 25 trillion bills—the gross global product—would be 1.7 million miles (2.7 million km) high, 3.5 round trips from Earth to the moon. Picture 10,000 dots (figure 1.2). If six of these groupings (60,000) fill a page, 300 million dots—the current population of the United States—would fill a book of 500 pages, and the human population on Earth would be an encyclopedia over 10,000 pages long. It takes about 20 seconds to count 100 dots; it would take 41 years to count 6.5 billion dots, assuming no breaks for meals or sleep. Our brains are poorly equipped to deal with such large numbers.

Although knowledge of our global effects is in the public consciousness, it is at a superficial level. Scientists have just begun documenting global environmental problems, their causes, some of their implications, and what it may take to reverse them. Global environmental effects of human behavior have been studied for only the past several decades, so that the implications of these global effects for the future of humanity are not yet known.

Peter Vitousek, a professor at Stanford University, was named among America’s best scientists by Time and CNN in 2001. He and his colleagues published several articles documenting humanity’s global influences on how Earth’s ecosystems function.4 They found that we humans directly or indirectly use half of all products of photosynthesis on Earth, we now cause nitrogen and phosphorus to enter global biological systems at twice the natural rates, and we are altering our atmosphere for decades to come. Some of these papers have been cited more than 500 times in the scientific literature over the past ten years, which are very high rates of citation for scholarly works. The attention these papers received, and the research they stimulated, illustrate that environmental scientists have only recently started to pay close attention to global environmental impacts.

FIGURE 1.2 Image of 10,000 dots. If 6 of these fill a page, how long will a book with 6.5 billion be?

A recent massive effort to account for human effects on the global biosphere, the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, documents the human influences on the Earth that supports us.5 This effort involved a global assessment by 1360 authors from 95 countries. The assessment was reviewed by an in de pen dent review board of 80 experts guiding 850 reviewers. The group found that 15 of the 24 ways that Earth supports humanity are degraded: fisheries, wild foods, fuel wood, genetic resources, biochemicals, medicines, water supply, air quality, regional climate, erosion, water purification, pest regulation, pollination, natural hazard regulation, and spiritual, religious, and aesthetic values. We are entering the “overshoot century,” where we are exceeding the capacity of Earth to support humanity.

Over the past 300 years, humans have caused unprecedented changes in and on the land, oceans, and atmosphere. For the first time in history, humans are having multiple effects on the global environment that sustains us, and these effects are accelerating. Human behaviors causing these effects are deeply rooted and will be extraordinarily difficult to change. Past societies have destroyed their local environments, but members of our species, Homo sapiens, are having effects that far exceed those documented at any other time in human history. We are altering the entire Earth that supports our lives and doing so without complete understanding of the ultimate effects of such alteration. Close your eyes, step off the edge, and see what happens. Is it a low curb or a gaping chasm? Are we hurtling toward collision with a nearby brick wall, or will our momentum and trajectory end in a soft landing far in the future? Humanity is just reaching the point where we can begin to understand the repercussions of our actions. Understanding may allow realistic hope for the future.

What Are the Biggest Problems on Earth and Their Root Causes?

A popular question when interviewing young people for achievement awards is: What are the biggest problems on Earth, and what will it take to solve these problems? This question implies a more personal question to the interviewee: What are you going to do to solve the world’s greatest problems? If all people seriously ask themselves this question, the world might end up a better place. After I had asked many students how they were going to solve Earth’s problems, it occurred to me that maybe I should ask myself the same question. This questioning led to thinking in the broadest and most general terms about the planet’s ability to support us.

My personal opinion is that the largest problems facing people on Earth are poverty (including the ability to feed humanity), the threat of nuclear war, the catastrophic spread of diseases from bioterrorism or human behaviors that encourage emergent diseases, and the effect of human pressures on Earth’s ability to sustain us. I do not know which of these problems is most important, but, clearly, poverty directly harms the most people right now. According to the World Health Organization in 2007, some 54 percent of the 10.8 million deaths per year of children under age five are directly or indirectly caused by severe malnutrition. Over 5 million children die each year, even though we have food to feed them. I do not have the expertise to offer insights into global poverty or the political nuance that fails to control hunger and that, so far, has controlled the danger of annihilation by biological or nuclear warfare and by epidemics of human diseases. As a biologist who studies the environment, I can most easily approach global environmental problems. This exploration took me into human behavior, particularly as influenced by biology.

“Save the Earth” is the slogan that most succinctly expresses environmental concern over global effects of humans, but does Earth truly need saving? As a scientist who studies freshwater and the plants and animals that live in it, I am astounded by the immense cumulative increase in evidence of human effects on our environment. Specialists are individually documenting negative impacts of humans on every ecological system on the planet. On land and in the sea, in remote areas and near large cities, on mountaintops and deep below Earth’s surface, the effects of human activities are becoming ever more pronounced. Each scientific meeting I attend and each research journal I read offers further proof of the collective negative effects of humans on our globe. Every human inhabitant on Earth has only a small impact, but the sum of 6.5 billion impacts is taking a serious toll on our world.

Appreciating trends that are occurring on a global scale is difficult because they are abstract, involve large geographic areas, require accounting with gigantic numbers, and are generally far removed from our everyday experience. Although basic understanding of the science of ecology is not strong among the general public, good introductory, nontechnical treatments exist.6 In addition, people living in North America and western Europe may not realize the degree of global degradation because in their countries many local environmental impacts have been minimized. A view biased by living in well-off countries allows technological optimists to claim that an increased standard of living leads to a healthier environment. The healthier environment myth evaporates when global accounting is used, but many traditional economists are partial to a worldview that discounts environmental costs. Negative costs of economic activities (called “externalities”) are difficult to assess. If you ignore externalities, and money is flowing into your pocket, things can look pretty good—in fact, much better than they actually are.

Unfortunately, environmental conditions are appalling in most developing countries because pollution controls are often not enacted or are poorly enforced in the face of poverty.7 Although the distinction between developed and developing countries is simplistic, in this book, I use the term “developed countries” to mean the United States and Canada and those in western Europe, along with Japan, Australia, and other countries with a relatively high standard of living. The least-developed or developing countries are in Africa, Asia (excluding Japan), Latin America, the Caribbean, and the regions of Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Two-thirds of the people on Earth live in developing countries, and about one-half of those live in extremely crowded and polluted cities.

People everywhere care about their environment. Gallup International surveyed 50,000 people from 60 countries for its Millennium Survey and found that health and family life were most important to respondents. A majority, 57 percent, think the current state of the environment is unsatisfactory. People in only five of 60 countries think their government is doing enough to protect the environment.8 Why do people say they care about the environment but continue to damage it and, potentially, their own health? In part, the disconnect between environmental concern and actual behavior could stem from the inability to comprehend environmental trends at such a large scale and the true implications of those trends.

The ultimate reasons for human-caused environmental damage on a global scale are the patterns and ecological impact of resource use and population growth. Resource use must be considered because it is not simply the number of people on Earth but the effect of each person that determines environmental momentum.9 Trends in human population growth and resource use at the global scale have a tremendous amount of momentum because of the sheer number of people involved and the size of the planetary ecosystem. The longer we wait to control the root causes of global environmental problems, the more momentum they gain and the less likely we are to be successful in protecting the Earth that supports us. Is it too late? If I thought so, there would be little point in writing this book.

Optimism, Pessimism, and Hope

How do we respond to environmental issues that are so large? Many people react strongly against “gloom and doom” environmentalists. Complete pessimism leaves no room for hope. The dichotomy in the environmental debate over global human effects has been well defined since the 1960s, when concern over the...