![]()

1. The Deer Camp

THE HUNT

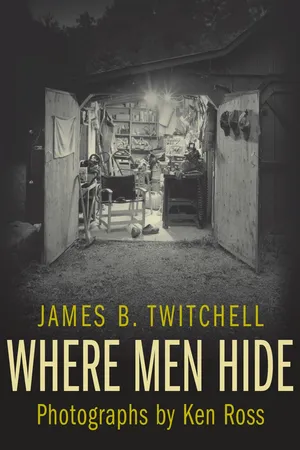

Deer camp, west view, Vermont

What you see before you is distinctly American. It is a hunting camp, more specifically a deer camp. The word that best describes it is ramshackle, a word that holds within itself a curious prediction. A ramshackle construction is something so poorly made that its imminent disintegration is embraced by the builder. In other words, he builds it in order to keep on repairing it.

Look carefully at the room and you can almost hear the stuff falling apart. Those drooping polyurethane lines carrying water to the shower will fall, the beer signs will need to be hammered back in place, and the bunks will soon separate. Part of the ritual of a deer camp is the “opening up” of it every season. The men of this camp (a woman has seen this sight only a handful of times) like it that way. This is a lair, a den that needs yearly tending.

In fact, its run-down, beat-up, jerry-built insubstantiality is what gives it substance. What gives it meaning, however, is the nearby tree, a deer tree, with rope hanging from a branch. Every deer camp has one; it is totemic. And one more factoid: all the men who use this camp could easily commute from home to these woods. They don’t come here to hunt. They come here and hunt.

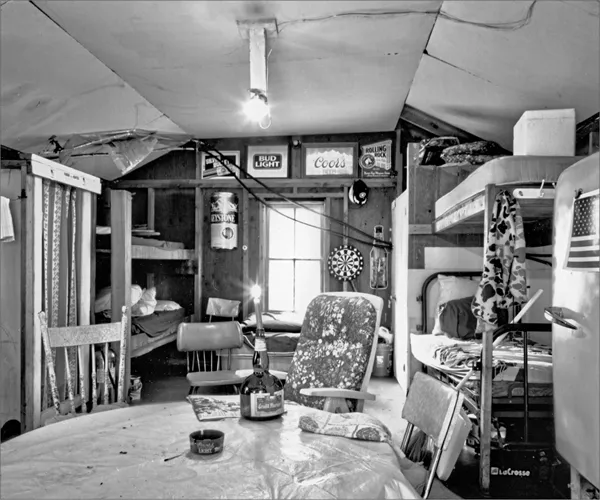

Deer camp, east view, Vermont

Almost every object you see here has a deep history shared by the men. Most camps have a collection of pictures, some of past events, some pornographic, either tacked up or in piles. The walls are plastered with memorabilia, the pots and pans are stashed in particular places, antlers may be hung over the door. A gun rack, a potbelly woodstove, a toilet with a number of problems, some hats on the wall, often a collection of rhapsodic poems and short stories about hunting, playing cards, and a cribbage board—all these items are part of the ritual of the yearly trip to deer camp.

Deer camp is also notable for what’s not here: television, phone (including cell phone, but some hunters use walkie-talkies), radio (but not weather radio), and usually women. Most deer camps I’ve seen have no electricity; instead, propane fuels the lights, stove, and refrigerator.

While you might think that this space exists elsewhere in the world, such is not the case. In almost all other countries—certainly in Europe—deer hunting is organized by social rank. In this country it is done by democracy. All hunters are equal and all are dishwashers, at least for a while. What we call a camp, Europeans call a lodge. The one thing a hunting lodge is not is ramshackle.

Two circumstances explain this strange hideout. The first is that the deer hunted in North America is the whitetail, while in most other places the quarry is red deer. The whitetail is shy, solitary, and easily spooked. He likes thickets and deep woods. Only when rutting does he congregate. Otherwise, he’s a loner. The red deer, however, is gregarious, moves in a herd like caribou, and prefers the open spaces. So if you want to hunt the whitetail you have to head for the hills. If you want the red deer you shoot from a stand as the animals are driven past you. The prize red deer is the stag with the most elaborate horn display. From his protected and often quite elegant station, the red deer hunter has a good idea before he shoots which stag will be his. Woe to the underling who shoots the wrong deer.

The other reason for this ramshackle hut is far more important. In most of the Western world, nature belongs to the rich. They own it and the animals that pass through it. The land for the rest of us is called just what it is—the commons. In fact, until the nineteenth century, sumptuary laws governed the taking of red deer from any land. Stags were part of what was called the king’s deer. Like coffee, the color purple, styles of fashionable clothing, particular fabrics, spices and sweeteners, stags were off limits to hoi polloi. Almost always the proffered reason was extravagance—these objects were sumptuous—but in truth the prohibition on hunting stags was a means of keeping class demarcations in place, of showing not just who owned what but who made the rules. Cross this line and you became a poacher. In North America, hunting land belongs to whoever bands together and stakes a claim. (Or at least it did.) The venison belongs to the hunter, not to the landowner.

While the goal of whitetail hunting is the buck, the male of the species, exactly which buck is not up to the hunter to decide. In American hunting the trophy rack is more the result of hunting savvy and woodsmanship than of the minions who have flushed the prize past the stand. The American hunter has to go into the woods. Often he has to make camp in the woods. Plus, he often has to field-dress and drag his several hundred pounds of buck out of the woods. Not so for his European counterpart. So the American hunter is by the very nature of his activity rewarded by cooperation, fellowship, local knowledge, and shooting skill.

And that is at the heart of deer camp. Whereas hunting divides classes in Europe and separates the lower classes from nature (after all, it’s not theirs and if they trespass they will be prosecuted), American hunting unites classes and creates camaraderie. Hunting leads not to a confrontation with nature but a connection to nature, and not against men but among men. The bond among hunters has its etymology in the comradeship of war, literally the esprit de corps, and comes itself from the oldest kind of kinship, namely the banding together of hunters to make the kill. In so doing, the activity of deer camp is both a reiteration of ancient male bonding and a distinctly American version of man in nature. In fact, sociologists who have studied deer hunting have a specific term for this quasi-military mutation—rough camaraderie.

Much of the cultural meaning of American deer hunting comes from three sources, two fictional and one actual. The popular novels of James Fenimore Cooper introduced readers to the first great backwoods hero, Natty Bumppo, who epitomized the coming clash between individual and communal impulses. Bumppo, aka the Deerslayer, is a foil to Judge Temple, the personification of bourgeois-controlled society. The judge wants the rule of man’s law to prevail. The old hunter, on the other hand, lives in harmony with the land and heeds the law of nature. Needless to say, we know who carries the day—at least in fiction.

The next great figure entering the mythic deer camp is Teddy Roosevelt, decked out in custom-fitted deerskin togs sewn by New York tailors, carrying a Bowie knife from Tiffany slid into a silver scabbard, and hefting whatever new model of Winchester was delivered especially to him by the company. Never underestimate the influence of Teddy in the development of American manhood, for it was his rough-and-ready narrative that connected hunting with training for war, rough camaraderie, and bully-good fun. Deer camp for him was “the wine of life” and every mother’s son should have a swallow. T.R. never tired of explaining that he was deer hunting in upstate New York on September 14, 1901, when word came to him that McKinley had been shot. Only for reasons like this should a man leave deer camp.

This same strand of deer camp mythography was picked up at the middle of the century by the writer William Faulkner. When Faulkner was told he had won the Nobel Prize, his response carried in newspapers across the land: “I can’t get away. I’m going deer hunting.” Better sense and entreaties from his editor prevailed, and Faulkner did indeed attend the award ceremony. But on his return CBS News picked up the dialogue below and replayed it on the Omnibus show in December 1954:

“UNCLE IKE” ROBERTS: Where you been?

WILLIAM FAULKNER: Sweden.

UNCLE IKE: You got the prize I hear. That’s good. (Pause) Long time to deer season. Month or two anyway.

FAULKNER: We’ll get us the big one this year, you watch.

(quoted in Wegner, p. 47)

If you really want to appreciate Faulkner’s focus on deer hunting, however, you need only open almost any of his Yoknapatawpha County stories. When you read his hunting stories you understand the almost hallucinatory and certainly biological importance of the hunt. Look at Go Down, Moses (1942) or any of the stories collected in Big Woods in 1955 (“The Bear,” “The Old People,” “A Bear Hunt,” and “Race at Morning”), and you will see that the hunt, specifically the deer hunt, is the hub of a man’s life, with the spokes of history, family, friendship, honor, gender, and religion all joined at the camp. The hunt is a state of grace. You cannot separate the hunt from the hunters from the hunted. And so it is on the hunt that the young man comes into his own and celebrates his manhood in the communion of his camp mates.

There was something running in Sam Fathers’ veins which ran in the veins of the buck and they stood there against the tremendous trunk, the old man and the boy of twelve, and there was nothing but the dawn and then suddenly the buck was there, smoke-colored out of nothing, magnificent with speed, and Sam Fathers said, “Now. Shoot quick and shoot slow” and the gun leveled without hurry and crashed and he walked to the buck lying still intact and still in the shape of the magnificent speed and he bled it with his own knife and Sam Fathers dipped his hands in the hot blood and marked the face forever while he stood trying not to tremble, humbly and with pride too though the boy of twelve had been unable to phrase it then, “I slew you; my bearing must not shame your quitting life. My conduct forever must become your death.”

(1942, p. 184)

While deer camp has a rich fictional and journalistic history, it has an equally fascinating actual history. Deer camps flourished after the Civil War as men banded together to harvest the deer crop. Venison was not a delicacy but a necessity, but the banding together probably had more to do with the bonhomie of warriors returning home than with the necessity of the tribal hunt. Usually the camps were just tents, often war surplus, surrounding a cook tent. Until the turn of the century, the most common method of killing was by jacking or shining light into the animal’s eyes—hardly a technique mandating a group effort. This was also called fire-hunting, since often the light was nothing more than embers carried in a pan. The hunter would carry the pan around a stream or lakeshore until he found the quarry with the archetypal “deer in the headlights” look. As weaponry became more sophisticated, jacking was considered unsporting, but, of course, it still continues today, especially in those places where deer hunting is not sport but survival.

The white-tailed deer is a surprisingly hardy species. While wolves, bison, and elk were hunted to extirpation in the 1800s and early 1900s, deer were able to move deeper into the woods. Even so, around the start of the twentieth century the federal government estimated that only 500,000 whitetails were left nationwide. With regulation (at first a limit of four deer per hunter!), they bounded back. There are now an estimated 28 million in the country, almost a million more than what most experts consider manageable. In many places, as their deep woods habitat has been removed, the whitetails have attained the level of neighborhood pest. You don’t need to go to deer camp; just open up your back door. In many municipalities, more deer end up on the car grille on the interstate than on the deer tree next to camp. Still, deer camp lingers on.

So what characterizes modern deer camp? First, of course, the site is forever set into the amber of our remembered past. This is a place for men to hide, yes, but it is also a place for men to open up to each other and to the natural world that we have pushed asunder. There is some variation between New England, Southern, and Midwest camps in terms of size, placement, and style, but the key to camp is the nature of the buck deer’s elusive habits and regal headgear.

Deer hunting is done in the autumn when the bucks are in rut and their antlers sprout. Antlers are projections of true bone that grow from pedicles, small stalk-like structures above and in front of a buck’s ears. As days become shorter in late summer, male hormone levels rise, causing antlers to stop growing and harden. The velvet then dries and sheds within a few days. Now the buck is ready and looking for the doe—just as the hunter is looking for the buck. Surprisingly, antlered bucks make up only a small percentage of a typical whitetail population. In early fall, less than 30 percent of the population consists of antlered bucks; after deer season, as little as 10 percent. Many of the bucks have been killed, and others have lost their antlers after the breeding season and will grow new ones, usually larger, the following year.

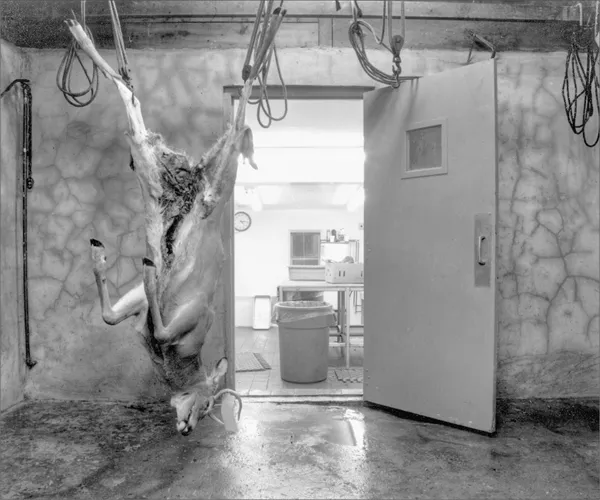

Deer and beer, New Jersey

Chick’s, New Jersey

Is there something primordial about men hunting the male deer at the very time when the buck is most masculine? You decide. If it helps you understand the deep structure, realize that one of the traditions shared by deer hunters across the land is that (as in the Faulkner passage quoted above), the young man’s first deer is memorialized by the rubbing of the deer’s blood across his face (baptism?). Should you want more dime-store psychoanalysis, try this: if the young hunter misses an easy shot or falls asleep on lookout (as is often the case because of the late-night bedtime), tradition has it that his shirttail is cut (castration?). The more egregious the miss, the greater is the amount of shirttail taken. Often this fabric is pinned to the wall of deer camp; sometimes it’s sent home to his wife or girlfriend.

The masculine nature of camp is reiterated in the names men give to their camps: Mad Dog, Neverhomeboys, Paradise, Lost Nation, Fort-Hort Resort, the Ruttin’ Buck Lodge and Resort. The food is hearty and full of what’s forbidden elsewhere—a cornucopia of carbs. Men tell jokes they’ve saved for months, or retell stories they’ve told for years. Here there are no food police telling you that sticky buns will ruin your waistline. No language police telling you to say “excuse me”; in fact, at deer camp escaping air more usually merits applause. No fashion police because all that nifty camo will be covered with fluorescent orange anyway. Manners are held in abeyance, jokes turn blue, there’s no shaving, bourbon appears before 5:00 p.m., cigar smoke turns the air to haze,...