![]()

PART 1

Pre-Qin Times

![]()

Tetrasyllabic Shi Poetry

The Book of Poetry (Shijing)

The Shijing (The Book of Poetry) is the fountainhead of Chinese poetry. The three hundred–odd poems that make up this anthology are the earliest extant Chinese verse. The edition used today was compiled by a certain Master Mao during the Han dynasty; thus it has become a convention to refer to the poems by their titles and their Mao numbers (1–305). The poems are divided into three sections (sometimes considered three subgenres), given here in their presumed chronological order: song (hymns, laudes [Mao nos. 266–305]), ya (elegantiae or odes, subdivided into greater and lesser ya [Mao nos. 235–265, 161–234]), and feng (airs [Mao nos. 1–160]). There are three subsections of hymns: those of the state of Lu (from the late Spring and Autumn era), those of the Zhou court (the earliest poems dating from the early Western Zhou), and the pieces imitating those of the preceding Shang dynasty (written in the late Western Zhou period). The greater elegantiae are concerned with the Zhou kingdom and its conquest of the Shang, and the lesser elegantiae are often connected to the various regional courts of the states under Zhou control. The airs, sometimes referred to as the “airs of the states” (guo feng), are broken into fifteen sections, thirteen ascribed to northern states or places and two purported to be collections of songs (referred to as nan [southern songs]) of the southern regions under Zhou rule. These poems treat a broad range of subjects and themes, from dynastic songs of cultural heroes to paeans of battles or warriors, court rituals or sacrifice, hunts and feasts. More than half the poems, most found in the “airs of the states” section, are love poems, long considered by most readers to be the most interesting texts. They are thus the primary focus of this chapter. Regardless of a poem’s subject, however, three basic modes of presentation have been identified by scholars: fu (exposition), bi (comparison), and xing (affective image). Although we have little evidence concerning the conditions of composition, it seems clear from the poems themselves that the hymns and elegantiae were probably composed at court, while the airs were originally folk songs that were standardized (in terms of prosody as well as content) for presentation at court.

These folk songs were composed in a social setting that predated Confucian mores. Thus liaisons between unmarried young men and women were not only allowed but encouraged (as the Zhou li [Zhou Ritual] tells us). This, in turn, resulted in many love affairs that ended in disappointment and despair, especially for the young women involved. Many of the airs are plaints apparently sung by these abandoned lovers.

Some of the prosody of these songs may have been the creation of these young men and women themselves, perhaps in part determined by popular tunes associated with certain affective images (xing); “on the mountains there is X,” for example, was usually employed in songs about separation. But the standards in this regard were no doubt established by the court musicians who helped shape these songs before they took their final form in the late sixth century B.C.E. It is possible that the three thousand poems Confucius was supposed to have examined before selecting the three hundred for this class were largely different versions of the same poems, distinguished by region or era.

The standards refined by the court musicians include a four-word line, the four-line stanza, various formulae, a general 2 + 2 rhythm, rhymes on even lines, and the use of various tropes, including metaphor, simile, synecdoche, puns, onomatopoeia, rhyming and reduplicative compounds, alliteration, and puns. Parallelism, especially in stock phrases such as “on the mountains there is X, / in the lowlands there is Y,” is common (for this particular pattern, see Mao nos. 38, 84, 115, 132, 172, and 204). Although there are no fixed syntactic rules, the pattern of topic + comment discerned by many in later Chinese verse is also evident in the Book of Poetry: “Tao yao” (The Peach Tree Tender [Mao no. 6]) begins, “The peach tree budding and tender,” and “Zai qu” (Driving the Carriage Horses) opens, “They drove on the carriage horses, clippedly clop.” Finally, it has been argued that there may originally have been some significance to the sequence of these three hundred–plus poems. Whether such significance existed or can be seen in the extant text is difficult to determine. Yet it is clear that reading one poem in the context of another, often contiguous text proves useful.

I present in this chapter examples from each of the three sections of the Book of Poetry. Although lines from these poems were employed early on by speakers to make a political point and this line of interpretation developed into an identification between the poems and early historical contexts, for the most part I will focus on literary interpretations.

These interpretations, although directed by commentators old and new and informed by parallel poems in the Book of Poetry, represent only one of a number of possible readings. Unlike early Greek verse genres, which were defined by musical accompaniment (lyric), subject matter (iambus), or meter (elegy), the “airs,” “elegantiae,” and “hymns” are labels that are less definitive. Even the origins of the poems in this anthology are still debated, with some scholars denying their oral provenance. Much has been left to the imagination of the modern reader of the Book of Poetry. Thus when we see a dance or a courtship rite in a particular poem—reflecting an ongoing folk tradition with similarities to that which produced “mountain songs” (shan ge) in later eras—other modern readers may prefer other readings. Such is part of the greatness of this collection.

Many of the texts, especially the love songs, need little interpretation. Yet through centuries of oral and written transmission of these three hundred songs, lines and even whole stanzas have been rearranged or lost. The situation admittedly is not as serious as with the Greek poetic fragments of the same period, where we find puzzling little snippets such as Archilochus’s (ca. 680–ca. 650 B.C.E.) fragment no. 107:

I hope that the Dog Star

will wither many of them

with his piercing rays.1

Who “many of them” refers to is unclear, but the clarity of the poet’s enmity for them allows this poem to resonate even with modern readers. Alkman’s (seventh century B.C.E.?) fragment no. 82 is similar:

The girls sank down,

helplessly,

like birds beneath

a hovering hawk.2

What is the context here? Although without more of the poem or a commentary it remains difficult to say, the sinister image of the hovering hawk and the vulnerability of young girls lying helpless appeal to us across time. Many of the poems collected in the Book of Poetry also lack contexts and have puzzled readers. One such song is “Zhu lin” (The Grove at Zhu [Mao no. 144]):3

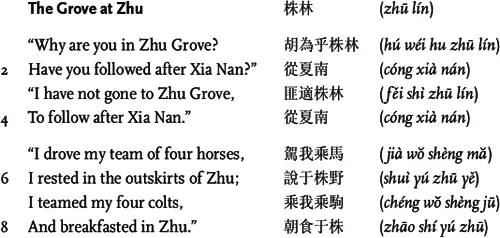

C1.1

[MSZJ 1.16b–17a]

As with the pieces by Archilochus and Alkman, the reader seeks a context for this song. Although the poem could be simply a love song about an anxious suitor, the references to the historical figure Xia Nan have caused most readers to identify the context of this poem with the affair between Duke Ling of Chen (r. 613–599 B.C.E.) and Xia Nan’s mother, as portrayed in the early Chinese historical text Zuo zhuan (Zuo Commentary on the “Spring and Autumn Annals”). There we learn that after continuing to see Xia Nan’s mother for some time, the duke insulted Xia Nan while they were drinking together. After the feast was finished, Xia Nan shot and killed Duke Ling with an arrow. The song was written, it is said, to satirize Duke Ling’s improper behavior. It is the duke who drove to Zhu. His impatience—he seems to have driven all night—as well as the erotic associations of the groves (where romantic liaisons were common), the racing colts, and even eating (breakfast) only heighten his impropriety even as he tries to excuse it. The demotic style and run-on lines of the final stanza, which allow the lines to be read quickly, suggest the duke’s urgency and his base nature.

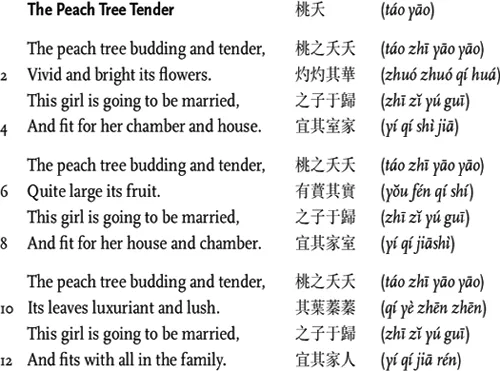

As fascinating as this kind of interpretation may be, most of the great poems of the Book of Poetry either provide their own historical background or need no contextualization, as we can see in “Tao yao” (The Peach Tree Tender [Mao no. 6]):

C1.2

[MSZJ 1.6b–7a]

This epithalamium is built around the comparison (bi) between the bride and the peach tree: she is also budding and tender, vivid and bright. The peach itself has associations in traditional China with female fertility, but here the emphasis is on the bride’s suitability for the husband and his entire family, with whom she is going to live. The flowers refer to her beautiful face, which will appeal to her husband in their bedchamber—thus the precedence given to chamber over house in the last line of the first stanza. In the second stanza, the implication is that her body will be capable of producing many sons, the main concern of her parents-in-law, who are represented synecdochically here by their house. By the third stanza, the emphasis has moved from the flowers and the fruit to the leaves of the peach tree, suggesting the passing of ...