eBook - ePub

Available until 27 Jan |Learn more

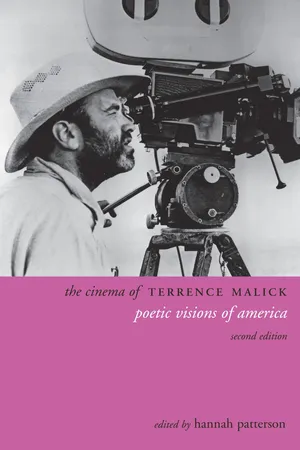

The Cinema of Terrence Malick

Poetic Visions of America

This book is available to read until 27th January, 2026

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 27 Jan |Learn more

About this book

With 2005's acclaimed and controversial The New World, one of cinema's most enigmatic filmmakers returned to the screen with only his fourth feature film in a career spanning thirty years. While Terrence Malick's work has always divided opinion, his poetic, transcendent filmic language has unquestionably redefined modern cinema, and with a new feature scheduled for 2008, contemporary cinema is finally catching up with his vision. This updated second edition of The Cinema of Terrence Malick: Poetic Visions of America charts the continuing growth of Malick's oeuvre, exploring identity, place, and existence in his films. Featuring two new original essays on his latest career landmark and extensive analysis of The Thin Red Line-Malick's haunting screen treatment of World War II-this is an essential study of a visionary poet of American cinema.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Cinema of Terrence Malick by Hannah Patterson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film Direction & Production. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

All Things Shining: The Struggle for Wholeness, Redemption and Transcendence in the Films of Terrence Malick

Ron Mottram

Why should we be in such desperate haste to succeed and in such desperate enterprise? If a man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer.

– Henry David Thoreau, Walden (1861)

Although this question is raised in one of the seminal works of nineteenth-century American thought and letters, it helps define the character and vision of Terrence Malick, who has avoided being swallowed up in the desperate enterprise of American commercial cinema and who has truly moved to the sound of a different drummer. That the result is the limited output of only four films over more than a quarter of a century simply reinforces the uniqueness of his vision and the seriousness of his purpose. The thoughtful consideration of philosophical, social and personal issues that is so evident in Malick’s films does not mesh well with the formulaic preoccupations of an industry largely devoted to profit and the fleeting value of glamour and fame.

In an age and culture dominated by the simplified lies of commercial and political speech, and the desire for diversion, Malick asks the kind of difficult questions that, in American intellectual history, link him to such writers as Henry David Thoreau, Walt Whitman, Herman Melville and James Agee. In a period in the history of the visual arts in which the image is often sacrificed to a shallow conceptualism, he restores the beauty and power of the image as a carrier of meaning. In so doing, he has revived one of the strengths of the silent cinema, linking it to a sophisticated use of sound in voice-over narration and music.

This essay will elucidate some of the formal characteristics of Malick’s films while linking his work to a number of the essential concerns and mythologies that have been central to American culture. Among these are the problem of the appearance of evil, the violation of nature in the world and in ourselves, the loss of paradise and the search for redemption, the barrenness of contemporary American life and the existence of violence as a reaction, the impingement of the urban and industrial on the pastoral, and the nature and meaning of war. It will explore the character of Malick’s imagery, narrative structures, voice-over narration, non-narrative events and images, and figure to landscape relationships.

Among the strategies that will be used in making this analysis will be that of a dual chronology. The films will be considered both in the order of their making (Badlands (1973), Days of Heaven (1978), The Thin Red Line (1998), The New World (2005)) and in order of the time period of their stories (The New World (1607–1616), Days of Heaven (early 1910s), The Thin Red Line (World War Two), Badlands (1950s)). The chronology of production dates will allow an analysis of his development as a filmmaker and the evolution of his style and formal strategies. The chronology of story time and setting will allow the films to be seen as a kind of American history that deals with issues such as the European imposition on and destruction of Native American culture, the passing of the pastoral myth, the questioning of belief in essential goodness and meaning, and the potential loss of meaning in the media-saturated environment of post-modern culture. As a body of work, considered from the vantage point of both chronologies, the films reveal an increasing difficulty in finding a human link to the natural world, personal and social ‘redemption’, peace and truth in a place and culture that was originally perceived by some of its founders to be a new Promised Land, and significance in a world in which the problem of evil has emerged in apocalyptic terms.

At the heart of all four films is an Edenic yearning to recapture a lost wholeness of being, an idyllic state of integration with the natural and good both within and without ourselves. Even Badlands, which on the surface seems bereft of acts or thoughts of goodness or wholeness, treats this yearning metaphorically and to a degree ironically. Holly’s father paints a billboard that renders a peaceful rural scene with an idealised family. In his own house he has created a shelter from the contemporary world, simple and nostalgic in its decoration. Even Kit’s murderous journey is a perverted struggle to find wholeness and a desperate attempt to define selfhood. In place of a real identity, he imitates James Dean. While Dean became an icon of alienated youth, Kit is only an image of an icon, trapped by his apparent nature and, from the perspective of the time of the film’s making, by a popular and violent culture recently emerged from the Vietnam War, unsure of its present and its future, and unable to understand its past.

Everything in Kit and Holly’s world is played out in a moral vacuum framed by Holly’s naïve narration and analysis of events. The only things that stand in contrast to their world are the bits of the natural that survive amid the detritus of industrialisation. Animals still live in the grass, the plains are still vast and empty, sunsets still light up the sky and birds still circle overhead, but what is their relation to the events and actions to which they bear witness? More than a simple opposition, Malick’s use of nature and natural beauty rises to the level of a powerful sign for a higher good. Although most evident in The Thin Red Line and The New World, this signification is also present in Badlands and Days of Heaven and reveals an aspiration to understand the essential contradiction of darkness and light and to transcend it. In this is also revealed a high seriousness of purpose that links Malick to both Melville’s exploration of the origin and meaning of evil and Thoreau’s transcendental vision of nature as a link to a deeper reality.

‘What’s this war in the heart of nature?’ asks Private Witt in the first narration of The Thin Red Line. ‘Why does nature vie with itself? The land contend with the sea? Is there an avenging power in nature? Not one power but two?’ As these words are being spoken, we see no images of war, just those of a peaceful nature and human community. The island paradise of the opening, however, is quickly replaced by the fear and horror of battle.

In each of the films, a character attempts to create and live in an idyllic world. In Badlands, Holly’s father seeks order and a past in his house; the Farmer in Days of Heaven lives in a pristine Victorian mansion in the middle of vast and fruitful wheat fields; and Private Witt is AWOL in a native village in which all appears to be harmonious. Surrounding these three idyllic refuges, however, are dangerous and violent modern worlds that call into question the possibility of redemption from evil and the achievement of a sense of the wholeness and integration of all things. Even more conflicted, Captain John Smith in The New World is torn between his life and past as an English soldier and adventurer and his love for Pocahontas and the world of the ‘Naturals’, a world that is progressively lost for both him and the Naturals themselves. Nevertheless, the images of light shining through leaves and glancing off water, of wind blowing through wheat and grass, and of deep blue skies and sunsets suspended over the land function as a bridge to another world and as a sign of its existence.

At the same time, Malick does not close his eyes to the problem of evil. ‘This great evil, where does it come from?’ Witt asks in The Thin Red Line. ‘How did it steal into the world? What seed, what root did it grow from? Who’s doin’ this? What’s killin’ us? Robbin’ us of life and light? Mockin’ us with the sight of what we might have known? Does our ruin benefit the earth? Does it help the grass to grow or the sun to shine? Is this darkness in you, too? Have you passed through this night?’

These questions and speculations are those of the viewers, too. The journeys are the viewers’ journeys, which are also a pathway that leads through night. For this reason, Malick’s and the characters’ stories are the viewers’ stories, even if the immediate events are unfamiliar and set in the past. And for this reason and because of their high seriousness and fundamental importance as questions, the issues raised resonate in a way that is the province of very few films.

Badlands begins with Holly, a lonely teenage girl sitting on her bed, who, in voice-over narration, succinctly defines her alienated relationship with her father. It immediately cuts to Kit, a young man working on a garbage truck. Between their initial meeting and their final parting, the relationship between these two isolated people is played out against a backdrop of the Dakota badlands, empty, beautiful and full of promise, while leading nowhere and dotted with remnants of civilisation and industrialisation. It is a landscape punctuated by brief idyllic moments and sudden violent acts. Above all, there is a perpetual sense of alienation and isolation of every character in the film, from each other, their environments, society and themselves. It is represented in a variety of ways: for Holly’s father in his solitary work painting the billboard and in the interior of his house, drenched in the past; for Holly in her self-professed lack of friends and in the number of times she is seen framed by elements of the film’s architecture, between parted curtains, in doorways, in windows and reflected in mirrors; for Kit in his moody pacing and staring, lack of ambition and concern, the number of times he is seen alone, and in his sudden and unprovoked acts of violence; and for Cato in his slow reactions and sedentary life in the small house set apart outside of town.

The emptiness of the characters’ lives, their emotionless reaction to death and violence, their overall detachment from events, and the casual indifference with which they face the future are matched by their physical surroundings. The general emptiness of the streets in towns, the expansive barren landscapes through which they travel, and the vacant roads, as if existing only for their use, act as metaphors for separation and for the absence of any structure for the nurturing or sustaining of a human community and its individual members.

Early in the film, Holly is seen looking out of her bedroom window at night watching two boys on a street corner. It is not clear what they are doing or saying to each other, but it is clear that Holly’s world is completely cut off from theirs, as she is cut off from her own childhood. This brief sequence is directly followed by one of Kit entering the almost deserted bus station to make a phonograph recording in a pay booth. While telling of their intended suicide, Kit is seen through the shattered glass of the booth, which is set in the middle of the space surrounded by darkness. The two sequences are the culminating images of the alienation of these two young people and set the stage for their flight.

Leaving Fort Dupree ends what can be thought of as the first idyllic section of the film, brought to finish by sudden violence. Two events precede this transition, the killing of Holly’s dog by her father, in punishment for her lying to him about Kit, and the launching of the red balloon that Kit had found in the garbage. The shooting of the dog presages the murderous acts to come, and the releasing of the balloon, at least from Holly’s point of view, the inevitable end of her relationship with Kit and of his ability to find redemption. As the balloon rises higher into a blue sky, Holly’s commentary invests the moment with meaning: ‘His heart was filled with longing as he watched it drift off. Something must have told him that we would never live these days of happiness again, that they were gone forever.’

Having lost ‘these days of happiness’, the romantic idyll gives way to Kit and Holly hiding out in the woods, where they build a tree house. In a sense they create a natural parallel to the artifice of the father’s house, their own separate world free from the demands of society. Yet, they are not really separate. They have rescued a romantic landscape painting, an Art Nouveau lamp, and a stereoscope and slides from the house and brought them into their wooded encampment; Holly still puts curlers in her hair; and they dance to Mickey and Silva’s song ‘Love is Strange’. As a sign of their adventure, Holly reads to Kit from Kon-Tiki, but the reality is that they continue to carry, as they will throughout the film, tokens of the world they have abandoned.

Like the earlier idyllic section, this one also ends in violence – the killing of the three men who have come looking for them. From now on their journey allows them only brief moments of respite: eating dinner with Cato; resting and re-supplying at the Rich Man’s house; and dancing to a Nat King Cole song in the light of the car’s headlamps. As they head for Canada, it becomes clear that the goal of the narrative is not to resolve the couple’s relationship or the issue of their crimes but to clarify the meaning of Kit’s actions and his growing celebrity in a world in which heroes no longer have to be good, they just have to be successful. In order to become heroes two decades earlier, Bonnie and Clyde had to link their crime to a battle against oppressive banks, which were foreclosing on poor people’s farms. Kit and Holly simply have to appeal to others’ desire to escape boredom and the ordinary and to lash out against the difficulty of making sense of things.

Their last two days together mark the climax of the story and a major turning point for Kit. While stopped for the night, Kit is seen with his back to the camera and with his rifle across his shoulders and his arms draped over it, looking like a crucified figure or a scarecrow in the middle of an empty field. It is sunset, and he appears to be staring at the horizon. The image suggests reflection and a conscious and transitional moment. It is followed the next day by their encounter with a train, the first appearance of the world outside theirs in some time, and the burial of a bucket containing artifacts and proofs of their existence. A brief and forced moment of kissing in the car just before the train first appears in the distance and dancing in the headlights that night mark the end of the relationship. The next day, she refuses to leave with him when the helicopter carrying lawmen arrives at the oil camp, and he takes off on his own.

Although Holly’s narration continues, Kit takes control of his own story. He discards Holly’s clothes and suitcase, and after a chase by the sheriff, he stages his capture by shooting out his own tyres, making a stone marker of the place of capture, and surrendering. No sooner do they have him in custody than the deputy remarks on how much Kit looks likes James Dean. In a way, the deputy becomes as taken with Kit’s self-constructed identity as was Holly. It is clear that Kit receives not only recognition in this sequence but also a strange kind of admiration and, from his own perspective, even sanctification. He has chosen to trade his life for a fleeting recognition of his existence, and in so doing he redeems himself in his own eyes. Had Kit lived in the late 1990s and had the film been made 20 years later, his status as a celebrity might have been confirmed in becoming a subject for reality television. As it is, the film stands as a commentary on the difficulty, if not the impossibility, of transcendence in the post-modern, post-Vietnam world.

In Days of Heaven, Malick returns to many of the ideas he explored in Badlands but on a more philosophical level and couched in imagery and events that are Biblical in nature. Like the earlier film, an act of violence initiates flight and a journey in search of a better life, which takes Bill, Abby and Linda to an idyllic natural environment that has the potential of becoming their Canaan. Like Abram and Sarai in the Old Testament, Bill and Abby pretend to be brother and sister, and the result of their subterfuge parallels that of the original story in the Book of Genesis. As God ‘plagued Pharaoh and his house with great plagues’ because he took Sarai into his house, thinking she was Abram’s sister instead of his wife (Genesis 12), the Farmer in Days of Heaven is also plagued, first by locusts which begin to destroy his wheat crop and then by fire as the result of his own violent response to the trick played on him.

The events in the Texas panhandle are foreshadowed in the apocalyptic descriptions of the end of the world that Bill’s young sister gives in her narration and which she says were prophesied by a friend named Ding Dong. On a larger scale this death and destruction models the immediate sufferings of the people she saw in Chicago: ‘We used to roam the streets; there was people suffering in pain and hunger; some people their tongues are hanging out of their mouth.’ In an attempt to flee this world of suffering, the trio run away from the streets of Chicago, from jobs in the steel mill, and from the consequences of Bill’s killing of the foreman. They travel with other migrant workers by freight train, seen at first in the distance crossing a bridge, much in the way the train appears crossing the plains in Badlands.

In the earlier film, the train signifies the existence of that permanent world beyond the immediate, temporary world that Kit and Holly construct in their flight. In the later film, it functions more as a link between the idyllic world of the wheat fields and the world outside, as does the airplane of the flying circus, the motorcycle that Bill rides on his return to the farm, and the car used for the honeymoon and later for escape after the Farmer is killed. The train carrying President Wilson on his whistle-stop tour also brings in the outer world and especially suggests the world war, which seems so far away. As idyllic as their lives appear to be, there is both trouble in paradise, seen in Bill’s and the Farmer’s mutual jealousies over Abby, and trouble in the world at large. The personal conflict and the international conflict are versions of the same problem, though different in scale. The national insignia on the planes of the flying circus and, especially, Abby’s leaving on the troop train at the end of the film signify the impossibility of escaping this interrelationship.

This interplay of elements and ideas is encoded in the structure of the film itself. The opening, including the credit sequence with its photographs, introduces the urban world of poverty and industrial work, the world of ‘people suffering in pain and hunger’. Nature is absent, the only water runs past a slagheap, fire is contained in a furnace, and the sky is darkened by factory smoke. In contrast, the wheat fields of the second section of the film present a world in which people seem to live in harmony with nature, the water is pure and cleansing, and the skies are defined in striking colours. Yet within this great natural beauty, human motives and passions pose the same danger of bringing suffering. The farm is also a world of exploitive work and war-induced profits in which power resides in wealth and the machine encroaches on the garden.

With the end of the harvest, the farm and its remaining inhabitants settle into an idyllic life in which play and leisure dominate, passions and deception slip into the background, and the cycle of the seasons brings nature to the forefront. Bill’s departure and apparent acceptance of the growing love of Abby for the Farmer removes for a time the remaining threat to this pastoral scene. However, like the return of planting and harvest, which culminates in the plague of locusts, Bill’s return reintroduces the seed of jealousy and conflict, which results in the conflagration of fire and the deaths of both Bill and the Farmer. In light of the Biblical connections of this narrative, the arrival of the locusts and the destruction they bring to the wheat suggests the possible existence of judgement and punishment for human actions or, at least, a joint appearance of evil in both the human and natural spheres.

Structurally, the fire which destroys the crop and the fire which destroys the house in Badlands serve a similar purpose, as do the killing of the Farmer and the killing of the father. The fires destroy worlds which can no longer exist and, in a sense, never existed in an ideal state, and the killings force the main characters to flee and result in death at the hands of the law. They also cause the main female characters to create new lives for themselves. The final sequence in the town reintroduces the world at large and elevates the primal conflicts in the characters’ lives to the wider scale of war. Although Linda’s world remains personal as she walks along the railroad tracks with her friend into an uncertain future, Abby boards a troop train and joins the country as it moves into even greater uncertainty of participation in the ‘war to end all wars’.

More than the first two films, The Thin Red Line transcends the immediate setting and action of the narrative to ask questions that penetrate to the heart of the Western mythos, such as the source and nature of evil, the existence of the spiritual, and the role and meaning of love. The existence of war as a great evil, especially on a world scale, raises the stakes of the discussion far beyond Kit’s murder spree and the interlaced jealousies and conflicts of Bill and the Farmer. The characters struggle with war itself more than they do with the Japanese enemy. Unlike most films about World War Two, The Thin Red Line is not concerned with the right or wrong of a cause but with the horror and meaning of the conflict for all involved. The war functions more like the great white whale in Melville’s Moby Dick, as a force that needs to be explained, than as a setting for the defence of political and cultural values or a theatre for personal courage.

The film begins with a metaphor. The island paradise, which serves as a hideaway and refuge for Witt, points to another world, one that Witt maintains a belief in despite the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction: Poetic Visions of America

- 1. All Things Shining: The Struggle for Wholeness, Redemption and Transcendence in the Films of Terrence Malick

- Through the Badlands into Days of Heaven: Malick’s Filmmaking in the 1970S

- Negotiating the Thin Red Line

- Discovering the New World

- Filmography

- Bibliography

- Index