![]()

CHAPTER 1

China’s Financial Markets: An Overview

Lee Branstetter

INTRODUCTION

This chapter provides an historical overview of the development of Chinese capital markets since the onset of the reform period. This important subject has attracted the attention of some of the best scholars working on China over the last 20 years. There is a vast literature for the reader to learn from and build upon. No attempt will be made here to be complete or comprehensive in covering even the major English-language contributions to this literature, much less the enormous volume of work published by mainland Chinese scholars in Chinese.

Instead, the goal is to provide the reader with a basic understanding of the key economic, regulatory, and market developments that have shaped the evolution of China’s financial markets up to the present. Whereas the other chapters in this volume focus to a significant extent on China’s financial future, one must begin with a clear understanding of the recent past. Given the space constraints, the coverage will necessarily be selective, focusing primarily on banks and equity markets.

In presenting this material, three main themes will be repeatedly emphasized. The first is the centrality of the state in the intermediation of capital in the Chinese economy, which has persisted to the present day.1 Chinese financial markets are dominated by banks, and the banking sector has been and continues to be dominated by state-owned banks, which, until very recently, have concentrated their lending on state-owned enterprises (SOEs). The equity markets have largely consisted of state-owned firms in which the state and its agents have retained a controlling, usually majority, interest. China’s dynamic non-state sector, especially its private firms, has been heavily discriminated against in the allocation of capital. Bond markets are dominated by issues of Chinese government bonds, and the right to issue fixed income securities has been tightly restricted.

This situation contrasts sharply with the general trajectory of Chinese economic reform since 1978.2 At the dawn of the reform period, the prices of nearly all goods and services were set administratively; by the mid-1990s, more than 94 percent of all prices were set by the market. Foreign trade in the late 1970s was highly restricted and monopolized by 12 state-owned trading companies; by the late 1990s, foreign-invested enterprises accounted for more than 55 percent of China’s imports and exports, and gross values of import and export flows were equivalent to 75 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). Industrial output was dominated by SOEs in 1978; this fraction has fallen substantially. Chinese labor “markets” were once characterized by lifetime employment, administratively set wages, strictly limited interfirm and geographic mobility, and a cradle-to-grave intrafirm welfare state. Today, Chinese labor markets function much more freely. China’s dynamic private firms can increasingly compete freely in the product market and the labor market—but access to capital, while it is improving, remains restricted. The increasing reliance on the market mechanism that is such a visible and striking feature of other aspects of modern Chinese economic life is much less evident in the financial sector.

The second related theme is that reform of Chinese financial markets has been inextricably bound up with the state’s efforts to reform and improve the efficiency of its SOEs, while retaining a large degree of ultimate control over them. When this goal proved elusive in the 1990s, the government accepted the need to downsize and privatize a large component of the SOE sector, but the state has consistently reaffirmed, at least rhetorically, its commitment to control the “commanding heights” of the economy by continuing to support (and direct) the largest and most important SOEs, including the most important components of the financial sector. From a Western perspective, the goal of retaining ultimate state control may conflict with the goal of pursuing maximum efficiency. This conflict may continue to limit the success of ongoing government efforts to improve the functioning of the country’s capital markets.

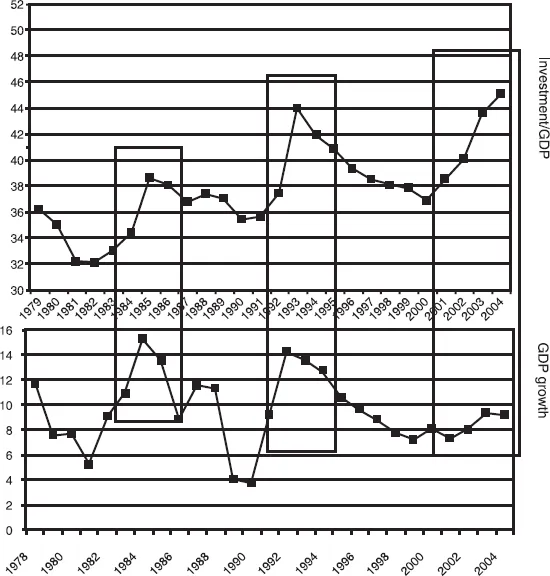

The third main theme is the context of macroeconomic instability in which Chinese financial markets have evolved.3 This can be illustrated by figure 1.1. The top graph shows the investment to GDP ratio since the early years of the reform period. The bottom graph shows real GDP growth according to the official statistics, which have been the subject of some criticism in recent years. Although real GDP growth has remained consistently positive throughout this period, the growth rate has experienced pronounced fluctuations that are closely related to rapid increases in investment relative to GDP.

Figure 1.1 China’s Investment-Driven Growth Cycles

Sources: Goldstein and Lardy (2004); National Bureau of Statistics.

China has already been through two investment-driven boom-and-bust cycles. The first, in the 1980s, was generated by an investment boom that led to serious macroeconomic imbalances, including rapid inflation, as well as the creation of excess capacity across a range of industrial sectors. The state had to sharply curtail bank lending, bringing investment back down to a sustainable level, but the result was a pronounced slowdown in macroeconomic growth. The second cycle came in the early 1990s. Deng Xiaoping’s endorsement of continued economic reform during his famous “journey to the South”4 touched off another investment boom even more dramatic than the one in the mid-1980s, financed principally by rapidly expanding bank loans. Once again, macroeconomic imbalances, including accelerating inflation, quickly became evident, and the authorities had to curtail bank lending, using a mix of sharp interest rate increases and administrative controls on the volume of lending. In the aftermath of this austerity regime, GDP growth slowed markedly and signs of excess capacity began to appear. Thomas Rawski (2001) has suggested that the combined effects of this slowdown, together with the onset of the Asian financial crisis in 1997, actually caused growth in the period from 1998 through 2000 to decline to considerably lower levels than the official GDP statistics suggest. Goldstein and Lardy (2004) estimate that roughly 40 percent of the loans extended during the early 1990s investment boom became nonperforming in the period of slower growth that followed.

The Chinese economy entered its third investment-driven boom in the early years of the current decade. Starting in 2002, bank lending and fixed asset investment began growing sharply relative to GDP. By 2004, the investment/GDP ratio had reached roughly 50 percent, an all-time high in recent decades.5 Despite a slowdown in fixed asset investment growth in 2004, the ratio of fixed asset investment to GDP for 2005 remained close to 50 percent.6 Over the past three years, real GDP growth has accelerated in response to the surge in investment, albeit to a lesser extent than in the past.7 As in earlier investment-driven booms, government officials have decried the creation of excess capacity, particularly in certain industrial sectors, and the authorities have imposed stringent limits on lending and investment. While there is no sign yet of any significant deceleration in real GDP growth, some concern has arisen that economic growth will decelerate over the next several years, as the overhang of excess investment is slowly absorbed.8

A number of market observers have pointed out, correctly, that the current investment boom has been financed, to a greater extent than in the past, by enterprises’ own retained earnings. Net external financing, most of it through bank loans, has only accounted for about 30 percent of enterprise investment in the current cycle, as opposed to 40–60 percent of investment in the investment boom of the 1990s. As a consequence, the inevitable slowdown may pose less of a risk to the banking system than the slowdown of the mid- to late 1990s.9 That being said, even proponents of this view concede that the current investment rate is likely to be unsustainably high, and enterprises that have overextended themselves may be unable to pay off their bank loans. This will probably trigger another substantial increase in the level of nonperforming loans (NPLs) in the banking system.10 A slowdown in corporate earnings and aggregate demand may complicate efforts to improve the functioning of the equity market. This macroeconomic context is critical as one considers the trajectory of financial reform over the next few years.

CHINA’S BANKING SYSTEM

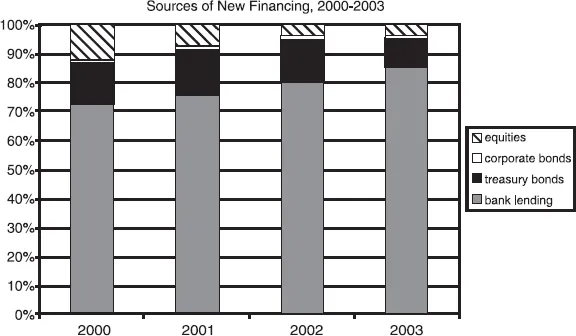

Chinese financial markets are dominated by banks to an extent that stands out even in Asia, with its history of bank-dominated financial markets. Chinese domestic equity and bond markets continue to play a relatively small role in the intermediation of financial capital to businesses in contemporary China. In 2003, lending by Chinese banks, as measured by total growth in loans outstanding, totaled 2.99 trillion renminbi (RMB). The total amount of funds raised on domestic capital markets, not including Chinese treasury debt or financial policy bonds, was less than 116 billion RMB—that is, less than 4 percent of the increase in loans outstanding. The sum of initial public offerings, secondary offerings, rights issues, and the sale of convertible bonds on domestic equity markets amounted to less than 82 billion RMB. Net funds raised by nonfinancial corporations through corporate bonds issuance was less than 34 billion RMB.11

Most other East Asian economies have traditionally had bank-dominated financial systems, but in many of those countries, the role of banks, at least in relative terms, has shrunk as domestic capital markets have developed and expanded. There is no sign of such a general trend in China, as can be seen in figure 1.2.12

For this reason, any discussion of Chinese financial markets, their history, and their evolution, will have to begin with a discussion of the banking system. I will begin by briefly reviewing the structural transformation of the Chinese banking system from a Soviet-style monobank on the eve of the reform period to the present.

Figure 1.2 Sources of New Funds

Source: People’s Bank of China.

FROM MONOBANK TO A BANKING SYSTEM—REFORMS OF THE 1980S

In the early years of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the private and quasi-private banks of the Republican era were either closed down or folded into state-owned financial institutions. By the dawn of the reform period, in 1978, China nominally possessed three separate state-owned banks, but in reality there was only one: the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), which simultaneously served as the chief lending institution and the nation’s central bank.13 The PBOC regulated the money supply, set interest rates, managed the PRC’s foreign exchange, and supervised the rest of the financial system. In addition, through a nationwide network of over 15,000 branches, subbranches, and offices, it controlled roughly 80 percent of all deposits and was the source of over 90 percent of all loans by financial institutions.14

The Bank of China (BOC) was effectively a subsidiary of the PBOC and specialized in handling foreign exchange transactions, working closely with the state-owned trading companies. The China Construction Bank (CCB), created by the PRC in 1954, operated as a branch of the Ministry of Finance, disbursing funds to approved investment projects that were part of the state economic plan; the funds came from the state budget. In reality, it was not a bank at all. There was a network of rural credit cooperatives, but their primary purpose was to mobilize rural savings—they did relatively little lending.15

In fact, the pre-reform banking system did relatively little lending in a modern economic sense. Household savings was very low relative to GDP. National savings were high but came primarily from the operating surplus of the state-owned industrial sector. This surplus was reinvested primarily through state budget allocations rather than lending per se. It is perhaps only a slight exaggeration to conclude that in the pre-reform era China lacked not only capital markets but also a banking system.16

Starting in 1979, the monobank began to evolve into a banking system with an increasingly complex and heterogeneous set of institutions. The Agricultural Bank of China (ABC) was reestablished with a mandate to focus on deposit and lending activity in rural areas, as part of the government’s broad strategy to improve the agricultural sector. In the same year, the State Council brought the Bank of China out from under the authority of the PBOC and expanded its business scope in order to support China’s rapidly expanding trade and foreign investment. Finally, the Construction Bank was elevated to similar status and allowed to take deposits and engage in lending activity rather than simply disbursing government funds.17

In 1983, the council decided to convert the PBOC into a central bank more on the lines of internationa...