![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

What Is the Problem with Natural Resource Wealth?

Macartan Humphreys, Jeffrey D. Sachs, and Joseph E. Stiglitz

There is a curious phenomenon that social scientists call the “resource curse” (Auty 1993). Countries with large endowments of natural resources, such as oil and gas, often perform worse in terms of economic development and good governance than do countries with fewer resources. Paradoxically, despite the prospects of wealth and opportunity that accompany the discovery and extraction of oil and other natural resources, such endowments all too often impede rather than further balanced and sustainable development.

On the one hand, the lack of natural resources has not proven to be a fatal barrier to economic success. The star performers of the developing world—the Asian Tigers (Hong Kong, Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan)—all achieved booming export industries based on manufactured goods and rapid economic growth without large natural resource reserves. On the other hand, many natural resource–rich countries have struggled to generate self-sustaining economic takeoff and growth and have even succumbed to deep economic crises (Sachs and Warner 1995). In country after country, natural resources have helped to raise living standards while failing to produce self-sustaining growth. Controlling for structural attributes, resource-rich countries grew less rapidly than resource-poor countries during the last quarter of the twentieth century. Alongside these growth failures are strong associations between resource wealth and the likelihood of weak democratic development (Ross 2001), corruption (Sala-i-Martin and Subramanian 2003), and civil war (Humphreys 2005).

This generally bleak picture among resource-rich countries nonetheless masks a great degree of variation. Some natural resource–rich countries have performed far better than others in resource wealth management and long-term economic development. Some 30 years ago, Indonesia and Nigeria had comparable per capita incomes and heavy dependencies on oil sales. Yet today, Indonesia’s per capita income is four times that of Nigeria (Ross 2003). A similar discrepancy can be found among countries rich in diamonds and other nonrenewable minerals akin to oil and gas. For instance, in comparing the diamond-rich countries of Sierra Leone and Botswana, one sees that Botswana’s economy has grown at an average rate of 7 percent over the past 20 years while Sierra Leone has plunged into civil strife, its gross domestic product (GDP) per capita actually dropping 37 percent between 1971 and 1989 (World Bank Country Briefs).

The United Nation’s Human Development Index illustrates the high degree of variation in well-being across resource-rich countries (Human Development Report 2005). This measure summarizes information on income, health, and education across countries worldwide. Looking at this measure, we find that Norway, a major oil producer, ranks at the very top of the index. Other relatively high-ranking oil-producing countries include Brunei, Argentina, Qatar, United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, and Mexico. Yet, many oil-producing countries fall at the other extreme. Among the lowest ranked countries in the world are Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, The Republic of Congo, Yemen, Nigeria, and Angola. Chad comes in close to the bottom at 173 out of 177.

Variation in the effects of resource wealth on well-being can be found not only across countries but also within them. Even when resource-rich countries have done fairly well, they have often been plagued by rising inequality—they become rich countries with poor people. Approximately half the population of Venezuela—the Latin American economy with the most natural resources—lives in poverty; historically, the fruits of the country’s bounty accrued to a minority of the country’s elite (Weisbrot et al. 2006). This reality presents yet another paradox. At least in theory, natural resources can be taxed without creating disincentives for investment. Unlike in the case of mobile assets—such as capital, where high taxes can induce capital to exit a country—oil is a nonmovable commodity. Since tax proceeds from the sale of oil can be used to create a more egalitarian society, one could expect less, not more, inequality in resource-rich countries. In reality, however, this is rarely the case.

The perverse effects of natural resources on economic and political outcomes in developing states give rise to a wide array of difficult policy questions for governments of developing countries and for the international community. For instance, should Mexico privatize its state-run oil companies? Should the World Bank help finance the development of oil in Chad; if so, under what conditions? Should the international community have “allowed” Bolivia and Ecuador to mortgage future oil revenues to support deficit spending during the recessions they faced in the past decade? Should Azerbaijan use its oil revenues to finance a reduction in taxes or should it put the money into a stabilization fund? Should Nigeria offer preferential exploration rights to China rather than requiring open competitive bidding in all blocks? Should Sudan use the proceeds from oil sales to support oil-producing regions or spread the wealth more evenly across different regions?

The chapters in this volume lay out a broad framework for thinking about these issues, a framework that seeks simultaneously to help countries avert the natural resource curse and address the myriad of serious questions on how a resource endowment should be managed. While an extensive literature on the resource curse exists, few books attempt to tackle this issue by drawing on both theory and practice, as well as on both economics and politics. In undertaking this task, we have asked leading economists, political scientists, and legal practitioners active in research and policy making on natural resource management to write down the key lessons they have learned on best practice for managing these resources. For concreteness, we asked them to focus especially on oil and gas, which makes for cleaner and more focused analyses throughout. While some features of oil and gas economics are specific to these industries, much of the logic and many of the proposals presented here can be applied also to other forms of natural resources. The result of their studies is a rich collection of analyses into the causes and patterns of the perverse effects of oil and gas and the identification of a series of steps that can be taken to break the patterns of the past.

But before we start exploring the solutions let us begin our study with an examination of the origins of the resource curse—why does oil and gas wealth often do more harm than good? The basic paradox calls for an explanation, one that will allow countries to do something to undo the resource curse. Fortunately, over the past decade, research by economists and political scientists has done much to enhance our understanding of the issues.

WHERE DOES THE RESOURCE CURSE COME FROM?

To understand the natural resource paradox we need first a sense of what makes natural resource wealth different from other types of wealth. Two key differences stand out. The first is that unlike other sources of wealth, natural resource wealth does not need to be produced. It simply needs to be extracted (even if there is often nothing simple about the extraction process). Since it is not a result of a production process, the generation of natural resource wealth can occur quite independently of other economic processes that take place in a country; it is, in a number of ways, “enclaved.”1 For example, it can take place without major linkages to other industrial sectors and it can take place without the participation of large segments of the domestic labor force. Natural resource extraction can thus also take place quite independently of other political processes; a government can often access natural resource wealth regardless of whether it commands the cooperation of its citizens or effectively controls institutions of state. The second major feature stems from the fact that many natural resources—oil and gas in particular—are nonrenewable. From an economic aspect, they are thus less like a source of income and more like an asset.

These two features—the detachment of the oil sector from domestic political and economic processes and the nonrenewable nature of natural resources—give rise to a large array of political and economic processes that produce adverse effects on an economy. One of the greatest risks concerns the emergence of what political scientists call “rent-seeking behavior.” Especially in the case of natural resources, a gap—commonly referred to as an economic rent—exists between the value of that resource and the costs of extracting it. In such cases, individuals, be they private sector actors or politicians, have incentives to use political mechanisms to capture these rents. Rampant opportunities for rent-seeking by corporations and collusion with government officials thereby compound the adverse economic and political consequences of natural resource wealth.

UNEQUAL EXPERTISE

The first problems arise even before monies from natural resource wealth make it into the country. Governments face considerable challenges in their dealings with international corporations, which have great interest and expertise in the sector and extraordinary resources on which to draw. Since oil and gas exploration is both capital and (increasingly) technologically intensive, extracting oil and gas typically requires cooperation between country governments and experienced international private sector actors. In many cases, this can produce the unusual situation in which the buyer—the international oil company—actually knows more about the value of the good being sold than the seller—the government of the resource-rich country. Companies can, in such instances, be in very strong bargaining positions relative to governments. The challenge for host countries is to find ways to contract with the international corporations in a manner that also gives them a fair deal. If, of course, there are large numbers of corporations that have the requisite knowledge, competition should be able to eliminate the rents associated with expertise, thereby allowing the resource-rich country to receive a larger fraction of the resource’s market value. But countries cannot always rely on the existence of such competition.

“DUTCH DISEASE”

Once a contract has been negotiated and the money begins to flow in, new problems arise. In the 1970s, the Netherlands discovered one of these problems. Following the discovery of natural gas in the North Sea, the Dutch found that their manufacturing sector suddenly started performing more poorly than anticipated.2 Resource-rich countries that similarly experience a decline in preexisting domestic sectors of the economy are now said to have caught the “Dutch disease” (Ebrahim-Zadeh 2003). The pattern of the “disease” is straightforward. A sudden rise in the value of natural resource exports produces an appreciation in the real exchange rate. This, in turn, makes exporting non-natural resource commodities more difficult and competing with imports across a wide range of commodities almost impossible (called the “spending effect”). Foreign exchange earned from the natural resource meanwhile may be used to purchase internationally traded goods, at the expense of domestic manufacturers of the goods. Simultaneously, domestic resources such as labor and materials are shifted to the natural resource sector (called the “resource pull effect”). Consequently, the price of these resources rises on the domestic market, thereby increasing the costs to producers in other sectors. All in all, extraction of natural resources sets in motion a dynamic that gives primacy to two domestic sectors—the natural resource sector and the nontradables sector, such as the construction industry—at the expense of more traditional export sectors. In the Dutch case, this was manufacturing; in developing countries, this tends to be agriculture. Such dynamics appear to occur widely, whether in the context of Australian gold booms in the nineteenth century, Colombian coffee in the 1970s, or the looting of Latin America’s gold and silver by sixteenth-century Spanish and Portuguese imperialists.

Globally, these shifts can have adverse effects on the economy through several channels. Any shift can be costly for an economy, as workers need to be retrained and find new jobs, and capital needs to be readjusted. Beyond this, the particular shifts induced by the Dutch disease may have other adverse consequences. If the manufacturing sector is a long-term source of growth—for example, through the generation of new technologies or improved human capacity—then the decline of this sector will have adverse growth consequences (Sachs and Warner 2001). Another channel is through income distribution—if returns to export sectors such as agriculture or manufacturing are more equitably distributed than returns to the natural resource sector, then this sectoral shift can lead to a rise in inequality. In any case, the Dutch disease spells trouble down the road—when activities in the natural resource sector eventually slow down, other sectors may find it very difficult to recover.

VOLATILITY

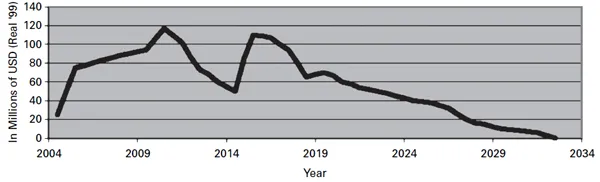

The Dutch disease problem arises because of the quantity of oil money coming in; other problems arise because of the timing of the earnings. Earnings from oil and gas production, if viewed as a source of income, are highly volatile. The volatility of income comes from three sources: the variation over time in rates of extraction, the variability in the timing of payments by corporations to states, and fluctuations in the value of the natural resource produced. As an example of the first two sources of variability consider figure 1.1, which shows one projection for Chad’s earnings from the sale of oil over the period 2004–2034. We see a sharp rise, followed by a rapid decline, a second rise, and a second decline. This pattern emerges from two distinct sources. The first is the variation over time in the rate of extraction. A typical pattern is to have a front-loading of extraction rates since production volumes tend to reach a peak within the first few years of production and then gradually descend until production stops. In practice, risks exist in Chad—as in Nigeria and elsewhere—that this volatility will be compounded further by interruptions that result from political instability in the country and in producing regions. The second major source of volatility derives from the nature of the agreement between the producing companies and the government. In the Chad case, the oil consortium was exempted from taxes on earning for the first years of production. Since taxes constitute a major source of government earnings, the eventual introduction of taxes should provide a major boost to Chad’s earnings.

Figure 1.1 Revenues to Chad, Base Case 917 MM BBLs, US$15.25/BBL.

Source: Based on estimates presented in the World Bank Inspection Panel (2000).

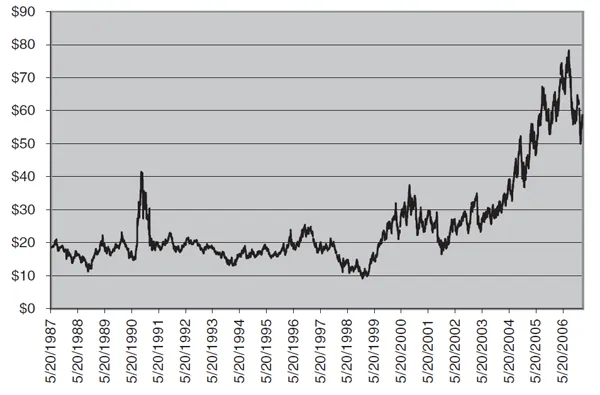

The third major source of volatility—not even accounted for in Figure 1.2—arises from the highly volatile nature of oil and gas prices. The figure presented by the World Bank is based on prices of $15.25 a barrel, a number that now appears hopelessly out of date. Figure 1.2 shows the price of oil over the past 20 years. Note that while there is a very clear upward trend over these years, the variation around this trend is very great with week on week changes of plus or minus 5 to 10 percent relatively common.

Figure 1.2 All Countries Spot Price FOB Weighted by Estimated Export Volume (Dollars per Barrel).

There are a number of difficulties with a highly volatile income source. Most obvious ...