![]()

PART 1

Rethinking Colonialism and Modernity

HISTORICAL AND THEORETICAL CASE STUDIES

![]()

[1]

A PERSPECTIVE ON STUDIES OF TAIWANESE POLITICAL HISTORY

Reconsidering the Postwar Japanese Historiography of Japanese Colonial Rule in Taiwan

WAKABAYASHI MASAHIRO

It is well known that in the 1980s, when Taiwan underwent significant political changes, Taiwanese history suddenly began to generate a great deal of domestic and international academic interest. Particularly in Taiwan considerable time and material resources have been invested in this field of study.

It is worth noting that prior to this, however, the Japanese colonial period received relatively little academic attention (Chang 1983:15–16). This was the result of both historical and political factors. Most historians of the subject have hurriedly explored merely the frequent shifts of political rulers and have come to the premature conclusion that Taiwanese history is but “the process of development of peoples of various ethnic origins coming from outside” (Wu 1994:229–230). Such historical evaluations of Taiwan actually privilege the viewpoint and the values not of the ruled but of the ruling class. Given this historiographical trend, we can say that Taiwanese history in the period of Japanese colonization has been “doubly exploited” (Wu 1994:230), in that “Taiwan” in the period of Japanese colonization was forced into a passive position and identified as merely a stage in the “Empire’s South Advance” (teikoku nanshin ). In the postwar period, Taiwan’s assigned passive position was taken for granted and depreciated as such in historical reviews. As a result, scholarly inquiry into this period was hindered. Studies on the history of Taiwan in the colonial period were undertaken primarily by Japanese academics in the postwar period. Although there sometimes are expressed in Japan’s mass media certain opinions that retrieve the past from the viewpoint of the colonizer, only a few such discourses exist, and these among academics. More common, however, are scholars who have tried hard to overcome such viewpoints and historical perspectives. These studies, however, are far from being proof that “Taiwanese history” has itself become a recognized academic subfield in history. This is because the previous scholarship constitutes, in practice, the study not of the modern history “of Taiwan itself,” but of “Japanese imperialism/colonialism in Taiwan”; that is, Taiwan in this period is only insofar as it is a part of the modern history of “Japan.” To be sure, studies regarding Japanese imperialism/colonialism in Taiwan are not without significance. Indeed, they form a necessary element in the designation of modern Taiwanese history as a legitimate field of study. However, the currently received approach cannot be considered a comprehensive history of modern Taiwan: several Taiwanese scholars have made these observations (Wu 1983:18; Ka 1983:25). What then is the study of modern Taiwanese history? What kind of relationship should operate between the history of modern Taiwan and the history of Japanese imperialism/colonialism in Taiwan?

I begin this paper with a critical revisit to my previous work and attempt to evaluate what analytic mode such a historical approach might have and to what extent a constructive relationship could be bridged between the two approaches mentioned above. The resource materials for the establishment of my working hypothesis are mainly my own works; thus, this paper has to be subtitled “reconsidering the postwar Japanese historiography of Japanese colonial rule in Taiwan.”

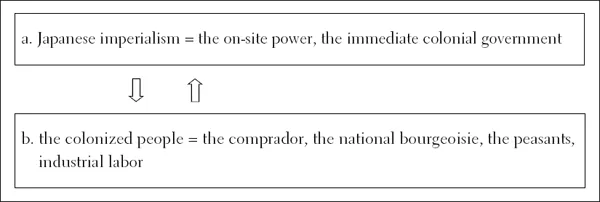

POLITICAL DYNAMISM IN THE TRANSFORMATION OF COLONIAL POLICIES: HARUYAMA MEITETSU’S “MODERN JAPANESE COLONIAL RULE AND HARA TAKASHI”

I have addressed the necessity of having a research perspective on the political history of Japanese colonialism in a co-authored book, The Political Development of Japanese Colonialism, published in 1980 (Wakabayashi and Haruyama 1980). This perspective was fully developed in Haruyama’s article “Modern Japanese Colonial Rule and Hara Takashi [also known as Hara Kei]” therein. Here I would like to review Haruyama’s work in order to determine in what ways this perspective might be useful to the current study. Before we wrote The Political Development of Japanese Colonialism, studies of colonial politics focused mostly on individual cases of resistance or on the nationalist movement in history. Perhaps we can put the issue in bolder, if not too reductionist, terms: these previous studies adopted an analytic framework that, based on a theory of binary oppositions, pitted “Japanese imperialism” against “the colonized people.” This focus on opposition generated two noteworthy results. First, these studies equate Japanese imperialism with the on-site colonial authority (the colonial authority that encounters, first hand, the resistance and opposition of the colonized). Second, these studies, mostly based on Marx’s theory of class, have identified the colonized people with different class categories and have treated these classes’ interactions with the on-site colonial authority. In so doing, these studies amount to a history of oppression and resistance that, as diagrammed in figure 1.1 below, is based on an old analytic mode: the problem consciousness as it relates to studies of the political history of Japanese colonialism.

FIGURE 1.1 Old mode: The problem consciousness in studies of the political history of Japanese colonialism

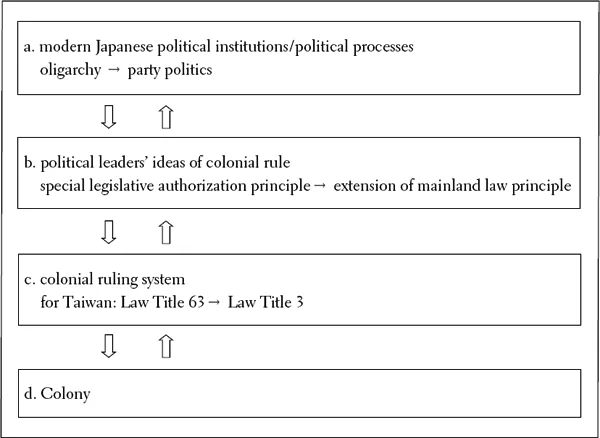

Haruyama has deviated from this old analytic mode. In previous studies based on the old mode, “although each individual colonial institution was mentioned respectively,” wrote Haruyama, “studies of the entire system of Japanese colonial rule are still lacking.” Thus, Haruyama continued, “this lack hinders our understanding of what political position the on-site colonial rule occupied within the entire Japanese state system,” and “it seems as though there is no relation between the development of Japan’s mainland political structure and its colonial rule” (Haruyama 1980:1). In order then to clarify the dynamic relations between the political history of Japan proper and the wider history of imperial Japan, Haruyama focused on a political leader, Hara Takashi, who played a significant role in the development both of mainland Japan’s political history and of imperial Japan’s colonial history. Haruyama’s resulting findings are diagrammed in figure 1.2.

A longtime leader of the political party Rikken Seiyukai (in existence since the late Meiji period), Hara Takashi transformed modern Japan’s political system from an oligarchy to a party-based democracy (see level a in fig. 1.2). He skillfully managed to play the politics of compromise and resistance with the existing oligarchy and helped install party-politics in the accepted political system. Through his efforts, Japan witnessed the successful establishment not only of the Imperial Diet (teikoku gikai ) as a state institution in which political parties functioned, but also of a party-based system that played a key role in the entire state system. In the midst of the Taisho period, Hara Takashi became prime minister of the first civil, party-organized cabinet in Japanese modern history. Immediately after he organized his Seiyukai cabinet, the First World War ended, and half a year later the March 1 Independence movement took place in Korea. Japan’s colonial ruling system experienced the profound effects of these events. FIGURE 1.2 New mode: The problem consciousness in studies of the political history of Japanese colonialism

In his article, Haruyama traced the development of Hara Takashi’s beliefs and political career and found that, long before becoming a politician, he had developed a model for Japanese colonial rule that was later to be called “the principle of the extension of mainland law” (naichienchoshugi ). Haruyama also discovered that Hara Takashi stood firmly by this idea when he engaged in debates over colonial policymaking within the Meiji government.1 On the difficulties surrounding the policy of the special authorization of colonial jurisdiction (the “Problem of Law Title 63,” rokusan mondai —that is, the controversy over the special legislative authority assigned to the governor-general of Taiwan), and on the problem concerning colonial administrative institutions (whether the military or the civil ...