![]()

PART 1

![]()

Las Piedras no son mudas.

Ellas solamente

guardan el silencio.

—HUMBERTO AK’ABAL

1

THE FERAL FORESTS OF THE EASTERN PETÉN

DAVID G. CAMPBELL, ANABEL FORD, KAREN S. LOWELL, JAY WALKER, JEFFREY K. LAKE, CONSTANZA OCAMPO-RAEDER, ANDREW TOWNESMITH, AND MICHAEL BALICK

THE NEW DISCIPLINE of historical ecology recognizes that human culture and the environment mutually influence each other (Balée 1998), rather than following the conventional one-way paradigm in which humans are ever adapting to their environments. We examine the contemporary Maya forest of the eastern Petén from this realistic vantage point, suggesting that its species composition and phytosociology are human artifacts dating from the Late Classic period. Wiseman (1978) was the first to use the term man-made to describe the Maya forest. About the same time, Turner (1978) and Hammond (1978) wrote the epithet for the Maya swidden and milpa, suggesting instead a much more sophisticated and biologically diverse system of mixed farming and silviculture. In an evolving series of papers, Edwards (1986), Fedick (1996a, 1996b; Fedick and Ford 1990), Ford (1986, 1991, 1998; Ford and Wernecke 2002), and Gómez-Pompa (1987) suggested that the contemporary forests of the Yucatán Peninsula were largely anthropogenic due to the ancient Maya’s manipulation of its species composition. Moreover, Gómez-Pompa, Flores, and Sosa (1987) provided a modern-day mechanism to explain this transformation—the Yucatec Maya forest garden, known as the pet kot—and they described how it was created and managed. Very simply, the Maya actively selected certain species in their gardens and discouraged others. Moreover, the boundary of pet kot and forest was not distinct. Each was derived from the other. Maya folk ecology reveals an intimate knowledge of myriad forest utilities (Atran 1993), and the Yucatecan Mayan language itself is evocative of the forest as garden: kannan k’ aax, translated as “well-cared-for forest,” implies a human curatorial relationship to the forest.

We agree that the contemporary forests of the southeastern Petén—that is, eastern Guatemala and western Belize—are anthropogenic, the result of the active enrichment, encouragement, and culling of various woody plant species by the Maya and of disturbance by periodic fires, whether intentional or unintentional, that swept the area beginning with the introduction of silviculture and agriculture in the Preclassic period. In other words, the contemporary Maya forest may be one huge feral forest garden, the origins of which date back to at least 4000 BP (Pohl et al. 1996).

We explore this historical ecological concept, however, from a vantage point different from history and archaeology alone: by using the analytical methods of phytosociology. Toward this end, we pose and test three hypotheses: (1) the alpha diversities of these forests are low compared to the alpha diversities of areas of similar latitude and climate that have not been submitted to such pervasive disturbance; (2) the beta diversity among widely spaced samples of these forests is small (in other words, the forests of the eastern Petén have a uniform species composition); and (3) the oligarchies of these forests are composed principally of species that were—and are—of economic value to the Maya.

RESEARCH BACKGROUND

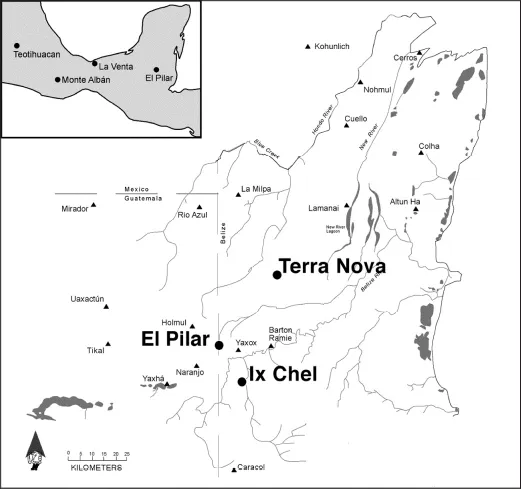

We conducted botanical inventories of three forest sites in distinct settings within 30 kilometers of each other, located in the Cayo District of western Belize (the extreme eastern Petén): El Pilar, Terra Nova, and Ix Chel (figure 1.1). All three sites were abandoned around 1000 BP and have not been recolonized or slashed and burned in any substantive way since. Our forest inventories were initially conducted in support of the Belize Ethnobotany Project (Balick 1991; Balick and Mendelsohn 1992; Balick et al. 2000), designed to provide data as to the diversity, quantity, and patterns of distribution of as many economically valuable plants as possible in Cayo District. For this reason, we chose the sites for their edaphic heterogeneity in terms of inclination, terrain, and drainage. El Pilar, the site of a major Classic period Maya city, is in the undulating, well-drained uplands on an escarpment north of the Belize River valley. Terra Nova is in the nearly level, poorly drained lowlands north of the Belize River and is the site of the world’s first ethnomedicinal plant reserve (Balick, Arvigo, and Romero 1994). Ix Chel is on a steep, rocky slope above the Macal River, the site of a medicinal plants trail (Arvigo 1992, 1994). The settlement densities of the Late Classic period on the sites reflect these patterns: El Pilar, Terra Nova, and Ix Chel represent a gradient of structure density during the Late Classic period of 200, 50, and 2 per square kilometer, respectively (Fedick and Ford 1990).

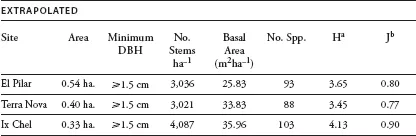

All woody stems (including lianas) greater than or equal to 1.5 centimeters DBH were sampled on each site (appendix 1.1). This criterion gave a far greater species number than the conventional 10 centimeters DBH threshold of inclusion (figure 1.3) used in the majority of phytosociological studies (Campbell 1989). We continued sampling until asymptote was approximated on a species-area curve, giving us a reasonable certainty that we had sampled most of the species in the area (figure 1.2). We measured the DBH of each stem, from which we calculated its basal area (for individuals with multiple stems or lianas, the sum of the basal areas), and the relative dominance for each taxon (table 1.3).

FIGURE 1.1 Three Maya forests.

We collected voucher specimens for each individual plant until we were confident of our ability to recognize discrete species (or morphocategories) in the field. Representative voucher specimens of every taxon were identified by comparing them with reference specimens in the herbarium of the New York Botanical Garden. For various reasons (such as damage or loss), we were unable to identify 4 percent of the plants to either species or morphocategory, so we classified these plants as “unknown.” We determined the Maya’s ethnobotanical uses of the species in our samples from the literature (for all linguistic subgroups of the Maya, not just the Yucateca Maya), as well as from interviews with contemporary Yucatecan Maya in Cayo District (appendix 1.2).

FIGURE 1.2 Species/area curves for three Maya forests.

FIGURE 1.3 The attenuation of information using the 10-centimeter DBH threshold of inclusion versus the 1.5-centimeter DBH threshold.

Since first being applied to the phytosociology of tropical forests (Peters et al. 1989), the word oligarchy has undergone various definitions (Campbell 1994; Pitman et al. 2001). In a general sense, it means that a small number of species usurp a disproportionate share of the resources—in terms of space and light, for example—while the majority of species scrap for the remainder. For this chapter, we define oligarchy as the subsets of 10 (and 20) species in each sample with the highest relative dominances. Having identified the species that comprised our oligarchies, we tested the hypothesis that the oligarchies were anthropogenic. The test involved: (1) determining whether the mean relative dominance of the oligarchic species was significantly higher than that of nonoligarchic species or than that of the forest as a whole and (2) whether the percentage utilization of the oligarchic species was significantly higher than that of the nonoligarchic species or than that of the forest as a whole.

ANALYSIS OF A FERAL FOREST

We identified 179 species in the three inventories of the El Pilar, Terra Nova, and Ix Chel forests. (They and the number and relative dominance of each are listed in appendix 1.1.) Table 1.1 summarizes the general parameters of the inventories: the area of the sample, the number of stems, basal area (extrapolated to one hectare), number of species, Shannon’s index of diversity, and Shannon’s index of equitability. The three sites showed a striking uniformity of species richness (93, 88, and 103 species, respectively) at approximate asymptote on the species/area curve. Each site also approached asymptote rapidly (figure 1.2), suggesting that a small sample—less than a hectare (and in the case of Ix Chel, a third of a hectare)—would be representative of the forest as a whole. Not surprisingly, therefore, the similarities (as measured by Sorenson’s index) among the various paired sites were also high, ranging from 0.46 to 0.61 for all species in the three forests (table 1.2).

Each site had a relatively low index of equitability (0.80, 0.77, and 0.90, respectively)—a hint of the presence of oligarchies described later, although the indices of similarity among the oligarchies of the three sites were more variable. Note that the oligarchy of Ix Chel appears to be the outlier among the three in terms of its species composition; we address this issue later in this chapter.

Among the 179 species found on the three sites, 76 (42 percent) were found to have been, or to be today, of economic value to the Maya (appendix 1.2). This value would appear to be low compared to the 80–90 percent utilization found in some other neotropical forests inhabited by Native Americans (Boom 1985); however, we did not count species that were used for no purpose other than “firewood” or “construction” in our analysis. When these species were added to our analyses, our sites had rates of utilization comparable to those of other neotropical forests.

TABLE 1.1 Summary of Three Maya Forests

a Shannon diversity index, (H) = – ΣPiInPi, where Pi = no. individuals of sp i/total no. individuals all spp. (Greig-Smith, 1983).

b Shannon equitability index, (J) = H(lnS)–1, where S = total no. spp. (Greig-Smith 1983).

TABLE 1.2 Indices of Similarity of Three Maya Forests

a H = 2a(2a + b + c) –1, where a = number of species common to both plots; b = number of species unique to area 1; c = number of species unique to area 2 (Greig-Smith 1983).

The species that composed the oligarchies (defined as both the top 10 and 20 species in terms of their relative dominances) of the three forests are listed in tables 1.3 through 1.5. Each of the three samples was highly oligarchic: the top 10 most dominant species in each forest usurped a minimum of 57 percent (and in the case of Terra Nova an astonishing 73 percent) of the forests’ footprint in terms of basal area. Species that are of economic importance to the Maya (appendix 1.2) are in boldface type in tables 1.3 through 1.5. Note that they comprise a majority of the species in the oligarchies, leading to the principal question of this chapter: Are the oligarchies anthropogenic? One way to address this question is cultural. At all three sites, the percentage utilization of the oligarchic species was significantly greater (P < 0.001) than that of the nonoligarchic species (table 1.6).

Another way to address this question is ecological and structural, by comparing the mean relative dominance of species of economic value to the Maya with those of no value (table 1.7). Again, at all three sites, the differences were statistically significant (ranging from P < 0.05 to P < 0.001). Moreover, a comparison of the mean relative dominance of those species not of utility to the Maya and the mean relative dominance of all of the species in each sample in every case proves not to be significant. These results imply that the oligarchy may indeed be the result of human selection. In other words, the species that have fared best in this forest over the past several thousand years have been those encouraged ...