- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Social Work Practice synthesizes the latest theories and research findings in social work and related fields and demonstrates how this information is used in working with clients. Because the interview is the medium in which much of social work practice takes place, learning the processes and skills to conduct a productive interview is a critical part of social work education.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I |  | CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORKS FOR SOCIAL WORK PRACTICE |

THE CONTEXT OF PRACTICE |  | 1 |

THE CONTEXT OF PRACTICE

Mastery of social work practice involves the integration of the knowledge and value base of the profession and a set of core interviewing skills with the “personal self” of the social worker. The behavior of the social worker in the social work interview represents an individual social worker’s unique expression of this combination of factors. It is difficult to imagine how effective service could be offered in the absence of social workers’ competence in using interviewing skills. It is through our interpersonal actions, the words we use, the attitudes and feelings we convey verbally and nonverbally that we may achieve whatever goals social workers and clients set for their work together. Hence interviewing skills can be seen as the primary tool of practice, and social workers need to know how to use them effectively.

But social work practice is more than technique. It is an integration of knowledge, values, and skill with a personal-professional self. The worker’s behavior reflects a set of values and ethical principles, a view of human and social functioning, an ideal about professional relationships, and specific perspectives on helping. Therefore, it is important to remember that the skills discussed in this book are only tools, and their usefulness depends on the rationale or intention underlying their use.

Values reflect the humanistic and altruistic philosophical base of the social work profession. Fundamental beliefs in human dignity, the worth of all people, mutual responsibility, self-determination, empowerment and antioppression, guide assessment and intervention (Reamer, 1999). Ethical codes of conduct and standards of practice specify how these values should be evident in a professional’s behavior. As the discipline has developed, some fundamental values and beliefs that have been expressed as practice principles have now received support from new theoretical developments and empirical findings. For example, social work has long valued the notion that a collaborative and strong professional relationship with the client is a crucial factor in bringing about change. Numerous practice models now embrace this concept and considerable empirical evidence also supports this long-held practice principle (Edwards and Richards, 2002; Norcross, 2002; Wampold, 2001). Social workers, guided by this knowledge, use interviewing skills purposefully to forge and maintain alliances between themselves and the people with whom they work.

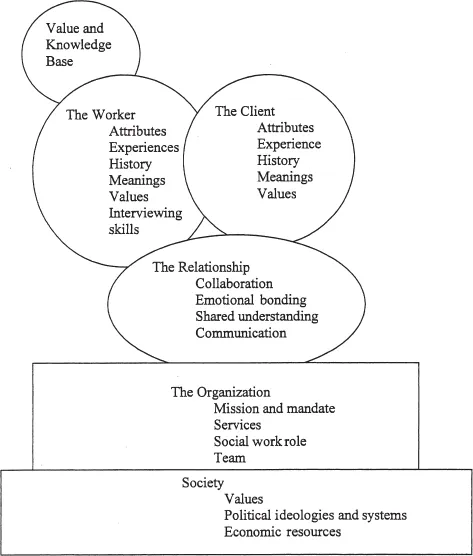

Conversely, knowledge and understanding of a practice situation remains solely an intellectual exercise unless evidenced in skillful communication with others. Analytic skills enable practitioners to assess situations and plan interventions so that practice is systematic and focused. However, it is through forming a working relationship or alliance with clients that a process occurs where, through dialogue and interaction, workers’ insights are offered. The interview is the medium of practice and the site in which intervention is largely delivered. Once again, it is the social worker’s skill in interviewing and her communication ability that affects whether professional knowledge will be received and experienced as helpful by the client. Figure 1.1 presents the elements that impinge on social work practice. These components or circumstances are relevant to understanding the process of helping and can also be referred to as the context of practice.

THE KNOWLEDGE BASE OF SOCIAL WORK

This text will present interviewing skills as the application of knowledge in practice and address how knowledge is assimilated for practice. In social work the knowledge base refers to many components; theory, models, wisdom, and specialized knowledge. Social work students are presented with a wide range of theoretical concepts that assist in understanding the human condition, social functioning, and dysfunction. These theories are ever expanding and reflect the explosion of knowledge over the past centuries. What is enduring is the profession’s interest in understanding the connections between the person and the situation. Theories therefore will include those that provide explanations of how societal structures may systematically oppress individuals and serve as barriers to social functioning, equitable participation in society, and the realization of their full human potential. Explanatory systems used are drawn from psychological and social theories. These systems provide concepts for understanding behavior with respect to growth, development, and individual and interpersonal functioning in cognitive, affective, and behavioral domains.

FIGURE 1.1 The Context of Practice

The knowledge base also includes practice models and their related intervention techniques. A model refers to a collection of beliefs about human functioning and what is needed to bring about change with clients who present particular problems and situations. For example, Perlman (1957) developed a problem-solving model for social work to help clients with personal and interpersonal issues. Models generally include techniques or actions that are extensions of the beliefs about the cause and nature of the problem and how to bring about change. Practice models are drawn from a wide range of sources including those developed in related fields concerned with well-being and mental health. Some models are empirically supported, having been studied in a systematic manner by researchers and found to produce positive outcomes for clients. Many models have not been subjected to rigorous testing, yet their proponents claim they are effective based solely on selected anecdotal support.

Social workers have also developed principles of practice through working with clients and conclusions drawn from their experiences. These principles may be referred to as practice wisdom and often reflect both a value stance and a pragmatic way of working. For example, “start where the client is” and “go at the pace of the client” are long-standing guidelines in social work that also reflect the value placed on working in a collaborative manner with the client.

Finally, since social workers often provide help by giving clients relevant information about a range of issues, they use specialized knowledge about conditions, resources, programs, and policies. One unique feature of the profession is that social work bridges the personal and the environmental. As frontline practitioners, social workers are in an excellent position to identify and document unmet environmental needs of groups of people. They are committed to advocate with and on behalf of at-risk populations for the development of necessary programs and services. Social workers therefore need to be highly knowledgeable about the specific conditions that clients present with, from housing, employment, and educational needs to those with special situations, for example, being diagnosed with a particular medical condition, living with violence in intimate relationships, or having experienced abuse in childhood. Box 1.1 provides a brief overview of what can be referred to as the knowledge base for social work practice.

THE SOCIAL WORKER

The personal and professional self of the worker has long been recognized as an important influence on practice and one that can powerfully affect client outcomes. Practitioners bring all their personal attributes and characteristics into their work. Many factors shape our personalities and our personalities in turn affect our work and comfort level in working with various clients. Personal issues related to the past and the present operate as active ingredients in the interpersonal encounter in practice. Social factors, internalized by individual social workers, are also pertinent. Social factors refer to social identity characteristics such as age, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, economic status, ability, often referred to generically as reflecting culture. Personal factors include unique personal histories in family and community and personality characteristics and styles. Social work students bring their individual personalities, social identity characteristics, experiences, and values to their studies in social work. Through academic courses and field education students develop into professional practitioners, having learned professional knowledge, values, and skills and integrated these components of practice into their personal self. They learn to identify their personal feelings, thoughts, reactions, and the meanings they give to events in their own life experiences. They learn how these factors may operate in their judgments and actions in practice with clients, in both helpful and unhelpful ways. An ongoing commitment of practitioners is to be mindful of the subtle feelings and thoughts that emerge when working with clients. A stance that values self-awareness helps us to learn more about ourselves, to develop more understanding and acceptance of our own internal experiences, and to ultimately be more able to work with a broader range of situations. Through self-awareness practitioners can remain genuine as well as intentional and purposeful in their actions in the interview, rather than reactive to situations they experience as anxiety provoking.

BOX 1.1. KNOWLEDGE FOR PRACTICE

Theories about human behavior in the social environment | Structures, society, physical, economic and political environment Power, privilege, and oppression Diversity Organizational development and functioning Individual development and functioning Family systems |

Practice models, procedures, techniques | Approaches to practice Focus on aspects of cognition, affect, and behavior Empirical support |

Practice wisdom | Values in action Practice principles |

Specialized knowledge | About populations, conditions, special circumstances, and needs |

Social workers’ behavior in interviews represents a complex combination of experiencing, knowing, thinking, and doing. The ability to use interviewing skills to achieve goals demonstrates successful mastery of these many factors. To reiterate an important point, possessing theoretical and empirical knowledge is not sufficient to help clients; nor is the ability to interview enough. Rather, it is how these components of knowledge and skill come together through the person of the worker that affects whether effective practice may result.

THE ORGANIZATION AND SOCIETY

An important contextual feature of social work arises from the fact that the majority of social work practice takes place in organizational contexts and is defined by the mission and mandate of the employing agency. Organizations in turn reflect the commitment and ability of a society, nation, or local community to care for the social and health needs of the population. Societies vary with respect to their beliefs and values about the appropriate role of the state in meeting universal basic human needs. Political ideologies and systems determine how economic resources will be distributed, the way in which all citizens will be supported, and the way in which disadvantaged groups will be assisted.

The mission of the organization defines what programs and services are offered and the roles for social workers. Social workers may find themselves in organizational contexts that dictate the approaches they will use. Driven by demands for quality and cost-effective services agencies are increasingly more focused on program evaluation. Accountability expectations demand that we review the effectiveness of our work and strive to discover and use the most helpful and efficient methods of helping. Practice research aims to demonstrate which programs, models, and processes lead to desired outcomes. As empirically validated approaches are articulated and adopted organizations are able to serve greater numbers of people. Unfortunately the field has been slow to engage in practice research. Instead new models are often adopted as a result of ideological shifts or attraction to charismatic proponents.

Increasingly, social work practice takes place in multidisciplinary teams. The function, role, and professional activities of the social worker are affected by the way in which the team members organize their work. Where the team is interdisciplinary in composition there may be more or less separation or overlap in roles. For example, social workers in the mental health field have increasingly experienced other professionals’ interest in psychosocial aspects of health and illness. In contrast, a social worker in an acute surgical unit is likely to have sole responsibility for these issues.

In primary social work settings teams can provide helpful education and supportive functions for their members. These teams provide consultation on specific clients as well as general continuing professional development for social workers. However in agencies reliant on managed care funding increasingly there is an emphasis on maximizing revenues and as a result there are fewer nonbillable activities such as supervision and consultation (Bocage, Homonoff, and Riley, 1995; Donner, 1996). Similarly, in organizations funded by local or national governments, reduced funding has led to less time devoted to team work. Workers may experience increased isolation and less opportunity for critical reflection on their practice, including the opportunity for developing increased self-awareness.

The social worker’s behavior in the interview reflects an amalgamation of many factors—knowledge, values, skills, personal and professional aspects of self—all within the organizational context of service. The way in which these factors find expression in the behaviors of social workers and the helping principles they choose is the result of a complicated cognitive and affective process where theory or concepts are used in some way, filtered through the individual social worker. This chapter will present a range of concepts that can help social workers analyze the links between interviewing skills, helping processes and principles, and the underlying rationale and issues that affect the way in which they are used.

While this text begins with a focus on the worker it is important to recognize that collaboration with the client is a primary feature of social work practice. Practitioners promote an interactive process that enables the client’s full participation. The client’s issues, circumstances, and reactions influence each step in the process. Practitioners must be flexible, able to provide leadership and a systematic, focused approach and at the same time able to work with the client in an inclusive and responsive manner.

HOW SOCIAL WORKERS USE KNOWLEDGE TO GUIDE THEIR INTERVIEWING BEHAVIOR

There is a prevailing view of professional competence as the application of rigorous specialized knowledge to problems presented to practitioners. In this perspective knowledge is developed and empirically tested in studies and produces principles, procedures, and techniques that can be applied to real-world problems. Social work practitioners can then search for and efficiently use the current best evidence about what works for a specific question. Referred to as evidence-based practice, this approach recommends that workers learn how to systematically and quickly find empirical literature and critically appraise studies and findings for their validity and usefulness to the situation presented by a current client (Gambrill, 1999, 2001a, 2001b; Gibbs, 2002). Social workers can then use the empirical knowledge to assess clients and design intervention plans. Thyer and colleagues (Thyer and Myers, 1998, 1999; Thyer and Wodarski, 1998) have argued that since researchers have demonstrated the effectiveness of specialized psychosocial treatments, ethical practice warrants the use of those models.

This view reflects the dominant positivist paradigm in contemporary health science professions and is both ethically and intellectually appealing. Certainly our confidence that we can offer helpful services is improved if we have a rigorous base to rely on. However, there are some practical and ideological issues that mediate unconditional adoption of this approach. Evidence-based practice is easily applicable to practice models that can be articulated, defined in treatment manuals, and tested through controlled experiments. In the mental health field this approach has yielded support for behavioral models but is less easily applied to models that are not as readily defined in operational terms. A further criticism is that evidence of effectiveness comes from studies that are conducted on samples that do not fully represent the population of clients served in everyday practice (Raw, 1998). Samples in many research studies use criteria that often exclude clients with multiple presenting problems and symptoms. In a naturalistic study of cross-cultural counseling, we found that many of the clients who approach the participating community agencies for assistance had a wide range of complex problems that included combinations of issues such as family conflict, social isolation and relationship problems, violence, depression, and need for employment (Tsang, Bogo, and George, 2003). Furthermore, outcomes reported in studies are for those clients who participate in the full program being tested and who comply with the approach. Generally, the studies do not investigate the clients who drop out. As a result the samples may represent a more motivated group of clients than those typically seen in social workers’ practice. Finally, evidence-based practice assumes the existence of a variety of useful studies upon which social workers can draw. In a recent review and assessment of the extent of research capable of informing practice interventions Rosen, Proctor, and Staudt (1999) found, of the articles published in a sample of leading social work journals, fewer than one in six were reports of research studies. Moreover, only 7 percent of these studies reported on practice interventions, whereas 36 percent of the studies contributed descriptive knowledge, and 49 percent contributed explanatory knowledge. The authors conclude that current social work research falls short of addressing the needs of practitioners for usable information about what works with whom, under what circumstances. While developing an empirically tested knowledge base is of great importance for all professions, it is however premature to conclude that in social work we have such information and that the challenge is only to find better ways of access.

Others have questioned whether sole reliance on empirical validation as a way of deciding how to intervene is appropriate or realistic for social workers (Witkin, 1998). Given the vast number of factors in individuals’ lives, in families, groups, and communities, it is impossible to completely predict outcome...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part 1: Conceptual Frameworks for Social Work Practice

- Part 2: The Process of Helping in Social Work Practice

- Part 3: Interviewing in Social Work Practice

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Social Work Practice by Marion Bogo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Research & Methodology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.