![]()

P A R T 1

Rites of Popular Life in Oaxaca

The culture of poverty in Mexico is a provincial and locally oriented culture. Its members are only partially integrated into national institutions and are marginal people even when they live in the heart of a great city….

Some of the social and psychological characteristics include … a strong present time orientation with relatively little ability to defer gratification and plan for the future, a sense of resignation and fatalism based upon the realities of their difficult life situation, a belief in male superiority which reaches its crystallization in machismo or the cult of masculinity, a corresponding martyr complex among women, and, finally, a high tolerance for psychological pathology of all sorts.

—OSCAR LEWIS, The Children of Sánchez

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Anthropology in a Mexican City

Death is our destiny: from the moment we are born we carry with us how many years we will live, the moment we will die. This is the destiny of life and death. But being poor is not our destiny, since there are many people who ended up rich after being born in poverty. It’s your goal to work, make money, and take care of it; if you don’t know how to take care of it you will never be anything but poor.

—DOÑA LUISA, AGE FORTY-FIVE

STUDIES OF DISTINCT RURAL COMMUNITIES made up the bulk of early-twentieth-century ethnographies of Mexico, especially those produced by North American anthropologists.1 Then, in the 1960s, as urban growth exploded and various forms of popular culture began to be of interest to anthropologists and other theorists of culture, a number of researchers began to study distinct urban communities or subgroups. One developing branch of this new urban anthropology was concerned with seeking general models that could account for lifestyles of the urban poor. This focus on the urban poor was generated, in part, because anthropological interest in urban Mexico (and urban locales elsewhere in Latin America) first followed the paths of rural migration to urban centers. Initially, researchers regarded the vast peripheral “squatter settlements,” visible in urban regions across Latin America, as zones of transition between traditional rural village existence and “modern” urban life; in such spaces, it was argued, the poor lived out their marginal station in life. Notions of “adaptation” and “acculturation” were developed to describe a process of rapid life change and accommodation to urban norms. Most discussion of “adaptation” or “acculturation” assumed that, in a fairly short time, new migrants to urban spaces were swallowed up by urban life and the capitalist economy, that they found a steady place in the city, even if that place was near the bottom of the economic heap.2

In 1961, in his well-known study The Children of Sánchez, the anthropologist Oscar Lewis proposed one of the most influential and remarkably persistent early models for making sense of life in an urban squatter community, the concept of the “culture of poverty.”3 As he wrote about it, the notion of “the culture of poverty” moved from an examination of the poor objective material conditions shared by many inhabitants of a marginal urban neighborhood to a whole set of inferences about shared values, normative structures, and behavior considered to be “characteristic” of such a place. Thus, having vividly described the texture of everyday life for a handful of residents, Lewis arrived at a series of conclusions about the “culture” or “consciousness” of poor squatters’ lives and communities. On the basis of such a paradigm of assumed shared consciousness or “culture” of poverty, parallels were sometimes drawn between widely geographically separated communities; further, center–periphery or dependency models, used in the analysis of international political and economic relations, were applied, by analogy, to interclass relations within the same society. Thus, for many years, those neighborhoods that stood physically, politically, and economically at the margins of a city were believed, quite simply, to also embody a set of attitudes and lifeways that stood at the cultural margins of the urban mainstream.

One of several anthropological attempts to conceptualize an “ideal type” of squatter settlement, which could then be analyzed within a larger framework in order to more fully interpret patterns of social interaction in urban spaces, the “culture of poverty” model aligned rather neatly with other, equally appealing, idealizing theories about “folk society,” including the celebration of such “rural” or “peasant” values as egalitarianism, social cohesion, and the centrality of family relations.4 Such idealized communities were often imagined according to theories that diametrically opposed them, as remnants of some happy past, to the disorganizing, secularizing, divisive forces and influences of modernized and “fallen” urban society. Despite the great evidence of social, political, economic, and cultural change entailed by large-scale movements of people to the cities, most idealizing community-based theories of the mid-twentieth century had little room for change; the communities they discussed were therefore all too frequently taken to be internally homogenous and economically, culturally, and geographically circumscribed.5 Even when the subject of study was how members of particular marginal communities were assimilated into the social, economic, and cultural “core” of a given city, rural life and urban life were frequently understood as static, dualistic, oppositional categories: a person was in one or the other, and historical connections between the two zones—complex modes of exchange, dependence, exclusion, privilege, and movement—were often downplayed or overlooked.

Criticism of static center–periphery models began in earnest in the 1970s, and, more recently, better accounts of the complex interactions between “culture” and “capital,” including a good deal of concern with patterns of movement—of people, goods, money, and various cultural forms associated with the globalization of trade—have considerably complicated the sorts of claims that may be made by an anthropologist who studies “marginal” urban communities.6 Distinct forms or patterns of cultural expression and behavior may indeed be found in such communities (as they are found in every community), but where these forms and patterns have come from, and what they mean in the lives of participants and the history of the community, neither is singular nor can be simply stated, as I hope this chapter will show.

Recent ethnography on Mexico has pointed to the need to recognize modes of cultural creation that cannot readily be pinned to specific, readily identifiable social communities or collective groups, but are products of the interaction between profound structural changes—such as urbanization, globalization, and the transition to “modernity”—and processes of social diversification.7 In these terms, then, “popular culture” subsumes a process of identity creation that is shaped by relations of power. In this book, I use the term colonia popular to designate a particular kind of neighborhood, but it is not equivalent to the popular community in its full significance. I am concerned with the “popular community” as formulated from a habitus or an ethos—a cluster of images, values, and deeply felt associations—that is produced in the course of daily social interaction. The “popular community,” then, is a dimension of social life in certain Oaxacan neighborhoods but does not represent it in any complete, unified way. In popular religious settings, a “popular self” is constructed at the interface of social interaction, certain moral schemes that prioritize “traditional” collective social relations, and ritual performance.

AN INTRODUCTION TO OAXACA

I first visited Oaxaca on a holiday in 1987. Struck by the beautiful colonial façades, the tranquility of the place, and the sweep of low mountains hanging protectively over the city’s northern edge, I found Oaxaca a welcome relief after the constant cacophony of traffic and human noise—not to mention the bothersome and persistent pollution—of Mexico City. Oaxaca was my introduction to the southern region of Mexico; it gave me my first sense of several of the very different economic and social landscapes enclosed within the country’s borders. In Oaxaca, I saw people whom I thought looked authentically “Mexican”—that is, Indian. Their appearance corresponded to some inner dream of an other, authentically Latin American place. Through a lens distorted by my fantasy, I saw in them extreme formality, deference to authority, and fervent religious devotion. Like other tourists, I was excited by sights such as the mystic ruins at Monte Albán and Mitla; by the indigenous peasant villages that surrounded the city, each devoted to a separate kind of artisanal production; by the rich cuisine; and by the warmth of the people I met—truly here was the “otherness” of experience I had been seeking.

In the decade and a half since my first visit, Oaxaca has changed enormously. Ten years ago, I was oddly shocked by a video game parlor that had opened up by the zócalo (town square). Today, Internet cafés are more ubiquitous in the city than in many urban centers in Canada or the United States; whenever you like, you can sip a foamy cappuccino or a café latte while checking your e-mail. These establishments compete for space in the now high-rent city center, or centro, with everything from companies doing Web sites, to pizza places, pricey art galleries, sushi restaurants, and vegetarian juice bars. On the street, cellular phones are more common than bicycles; a film by Federico Fellini or Woody Allen, shown at an alternative cinema, might be interrupted by the annoying whine of someone’s pager. A special sightseeing tram now takes visitors (mostly Mexicans, since foreigners still demand some colorful dream of authenticity) past noteworthy sites in the city center. Since I began my fieldwork in the city, traffic lights have been installed at many intersections where traffic was previously almost nonexistent; an increasing number of beggars and mounting problems of air pollution, water supply, and sewage all reflect the aches and pains of zealous growth and urbanization.

The old blind man I first saw more than thirteen years ago still sings his plaintive and beautiful songs on the cobblestoned Andador Turístico (Tourist Walkway), which runs from the colonial zócalo to the busy roadway leading to Mexico City that skirts the northern edge of the centro; occasionally, you can still see burros tied up outside the beautiful church and former convent of Santo Domingo, and people from indigenous rural towns may be heard speaking their local languages as they traverse the streets, some selling flowers, tamales, alfalfa, chapulines (grasshoppers), or furniture. An unmistakable greenish glow still emanates from the earthquake-proof, thick-walled limestone buildings that line the zócalo and streets nearby, lending a unique and undeniably mystic ambience to the city. Sweethearts still fill the benches in city parks on late afternoons and weekends. But such picturesque snapshots, as though of a disappearing past, although prized by visitors, cannot really stand as representative images of the place Oaxaca has become.

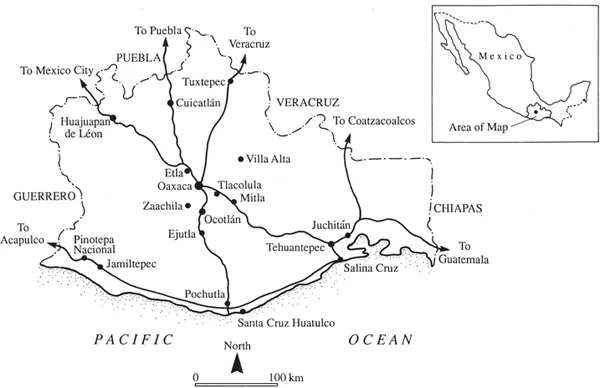

Oaxaca de Juárez (known simply as Oaxaca), the capital of the state of Oaxaca, is a city of some 250,000 people located approximately 180 miles south of Mexico City (figure 1.1). Both city and state are frequently characterized as spaces of pronounced cultural traditionalism, poverty, and a significant number of residents of indigenous background. The majority of the state’s 3.4 million inhabitants live in rural, indigenous settlements; there are 570 municipalities in the state of Oaxaca, in which sixteen distinct languages (excluding dialects) are spoken, which suggests a rather wide dispersal of political and administrative power in the state. Roughly 70 percent of the inhabitants of the state are of indigenous origin, giving Oaxaca the highest proportion of Indians in the country: about 18 percent of the nation’s total indigenous population.8 While the largest indigenous groups in the state are Zapotecs and Mixtecs, there are also Triquis, Chinantecs, Chontales, Mixes, Chatinos, Mazotecs, Chochos, Cuicatecs, Huaves, Zoques or Tacuates, Ixcatecs, Amuzgos, and Nahuas; there is also a small but significant Afro-Mexican population. This strong indigenous presence, and the paradoxical way it is used as the presentation of state identity, especially in tourism, is critical to understanding the texture of life in Oaxaca City; it has contributed to Oaxaca’s distinct cultural profile and to its political and economic marginalization relative to other Mexican states.

FIGURE 1.1 Mexico and the state of Oaxaca. (From Arthur Murphy and Alex Stepick, Social Inequality in Oaxaca: A History of Resistance and Change [Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991])

Being indigenous in Mexico is usually synonymous with being poor. Oaxaca is located in the southeastern belt of predominantly indigenous states, which include Chiapas, Guerrero, and Veracruz. Per capita incomes in Oaxaca are less than half the national average (Oaxaca has the second-lowest national per capita income, after Chiapas); state statistics are likewise comparably high for illiteracy, unemployment, death by curable disease, and lack of access to potable water, electricity, and well-maintained roads. Using these indexes, residents of 75 percent of Oaxaca’s 570 municipalities have been classified as existing in a condition of “high” or “very high” marginalization.9 In Oaxaca City, socioeconomic prospects for many residents are quite dim, despite the sanguine, energetic promises of slogans seen on political signs or billboards around the city: “Oaxaca: adelante!” (Oaxaca: forward!).

To complicate matters, rapid urbanization in the state has sharpened tensions and contradictions between urban (mestizo) and rural, peasant (indigenous) ways of life. In addition to widening the rift between rich and poor, government-propelled, neoliberal economic reforms and efforts to democratize the national political culture (partly responsible for the milestone victory of the Partido de Acción Nacional [PAN, National Action Party] over the dinosaur Partido Revolucionario Institucional [PRI, Party of the Institutional Revolution] in the presidential election of 2000) have been met by a blossoming of organizing from popular sectors, including a multifaceted indigenous movement that is fighting for indigenous autonomy. The effects of a regular out-migration of Oaxacans, especially to the United States, and the transformation of Oaxaca’s urban landscape to fulfill the increasing demands of international tourism, have accentuated the heterogeneity of the city’s population and urban culture. Indeed, Oaxaca may be seen to concentrate many of the contradictions and paradoxes of Mexico’s contemporary development in a globalizing world.

The boundaries of the city of Oaxaca have, over the course of the last several decades, expanded to include formerly rural towns. Although residents of many of these outlying colonias populares retain a number of ideas and practices common to rural indigenous communities, there is no doubt that the culture of Oaxacan urban neighborhoods, like colonias populares, consists of a mixture of the “new” and the “traditional.” While migrants from rural areas make an effort to adapt to city lifeways, they may also continue to sleep on reed mats, or petates; they may speak an indigenous language at home or consult a local healer, or curandero; they may use herbs when ill or when a doctor is beyond their means; they may keep and practice a number of popular or folkloric religious observances such as the death-related rituals I discuss in detail in this book. At the same time, as city dwellers, residents of the colonias populare...