- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Liquid Metal brings together 'seminal' essays that have opened up the study of science fiction to serious critical interrogation. Eight distinct sections cover such topics as the cyborg in science fiction; the science fiction city; time travel and the primal scene; science fiction fandom; and the 1950s invasion narratives. Important writings by Susan Sontag, Vivian Sobchack, Steve Neale, J.P. Telotte, Peter Biskind and Constance Penley are included.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Liquid Metal by Sean Redmond in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Film & VideoLIQUID METAL: THE CYBORG IN SCIENCE FICTION

| FIVE | LIQUID METAL: THE CYBORG IN SCIENCE FICTION |

In contemporary science fiction the cyborg is often one of the key signifiers of futuristic transformations driven by the melding of the machine with the human. The cyborg so often made of soft (human) tissue on the outside is at same time all hi-tech circuitry and computer chips on the inside. However, two distinct types of cyborg emerge in science fiction. The humanist cyborg is driven by the logic of the machine aesthetic and longs for the human emotion and human attachment that will add existential meaning to its fragile outer shell. He/she works with and for other humans, in democratic teams, with an important job to fulfil (as a science officer or engineer, for example). The humanist cyborg is constantly involved in situations that involve him watching and commenting on their colleagues as they fall in love, get angry, regret, and pass away. At key narrative moments they are called upon or challenged to act and react in the same way as their human compatriots. And while they seem incapable of this, fired as they are by objectivity and rationalist principles, and while they seem unable to bridge the emotional gap that is required of them, what is given away each time, through the use of a dramatic close-up that catches a forlorn glance, or an enigmatic reply, is a deeply hidden wish to be the same kind of human being. The humanist cyborg holds out for the hope (desire) of uniting and unifying the corporeal to the technological.

The pathological cyborg, by contrast, wants to melt away its human simulacra to symbolically rid the Earth (past, present and future) of what they rationalise to be is their fleshy, useless skin material and the flabby emotions that are tied to it. The pathological cyborg is programmed to be relentless in its pursuit of those who champion humanity and who stand in their path to greater, technological glory. They will stop at nothing, will undertake any and every heinous act to secure their will to power. The pathological cyborg wants nothing more than the complete genocide of the human race. The cyborg, nonetheless, always carries a weight of signification beyond its programmed impulses. Because the cyborg is part machine, part human, it necessarily comes to question the borders and boundaries of identity formation and the essential notion that there is a fixed and rooted trans-historical human condition. The cyborg is by definition a transgessive creation that plays out the power struggles over gender and sexuality, race and national identity, opening up potential spaces of resistance and opposition to masculine and feminine norms, and notions of otherness that circulate in ‘culture’ more widely. But, finally, the cyborg also stands as a form of cultural prophecy about the potential relationship between human and machine. On the one hand, the cyborg articulates the terror of letting too much technology into everyday life. On the other hand, the cyborg lives out the dream of corporeal and technological fusion where the gendered, sexualised and racialised body is left behind in a new (romantic) dawn of machine: human inter-dependence.

Donna Haraway’s feminist manifesto on the cyborg heralds its potential to transform identity from one being predicated on essentialised gender roles to one that swims in its own liminality. In what becomes a ‘post-gender world’, the cyborg is ‘about transgressed boundaries, potent fusions and dangerous possibilities which progressive people might explore as one part of needed political work’. Haraway marks out three key ways in which the borders of human identity have been breached in the late twentieth century: through human and animal fusion; human and machine fusion; and through the dissolution between the physical and the non-physical. In this cyborg world ‘people are not afraid of their joint kinship with animals and machines, not afraid of permanently partial identities and contradictory standpoints’.

Mary Anne Doane offers a critical account of the way the machine has been used in science fiction to re-confirm the essentialised relationship between women and ‘natural’ reproduction. Doane argues that because of a ‘revolution in the development of technologies of reproduction’ issues of conception, birth and the Oedipal scenario have been put into fundamental, cultural crisis. This crisis ‘debiologise[s] the maternal’ and, as a consequence, opens up the potential to destabilise the notion of Motherhood and the maternal. However, films such as Alien, Aliens and Blade Runner conservatively ‘strive to rework the connections between the maternal, history and representation in ways that will allow a taming of technologies of reproduction’ and a simultaneous re-centring of the link between the natural and the maternal.

Doran Larson examines the figure of the cyborg in relation to the way the American body politic functioned during the 1980s and 1990s. Looking at the two Terminator films, Larson argues that one can track a cultural shift in not only how technology is imagined in terms of democracy and notions of difference, but how the machine becomes ‘incorporated into the body politic’ by the appearance of T2 in 1991. This shift ‘reveals a popular surrender to the realisation that democracy in mass, capitalist society is inescapably technodemocracy: a body politic at best as cyborg, at worst on life-support systems’. Focusing on the Liquid Metal Man of T2, Larson argues ‘this figure epitomises – as no figure before morphing technology could have – the morphology of the oppositional logic in the body politic: it is the thing, now Indian, now Communist, which continually changes forms yet must survive if the body politic in democracy is to sustain its own morphology. And by presenting a threat that forces us to cling to the machine, we are forced back again … to rethink the Arnold from T1’.

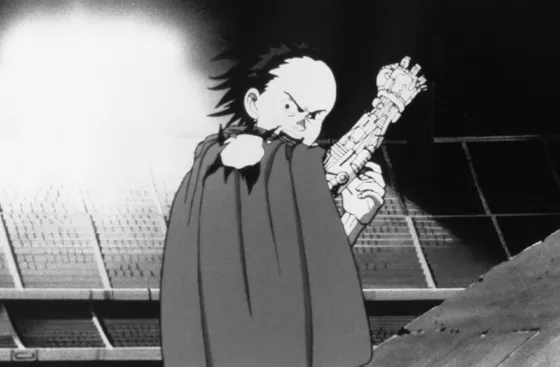

Susan J. Napier examines the ambivalent attitude to technology and the technological body in mecha (hard science fiction) anime – an ambivalence that she argues articulates deep-seated fears in Japanese society. According to Napier ‘while the imagery in mecha anime is strongly technological and is often specifically focused on the machinery of the armoured body, the narratives themselves often focus to a surprising extent on the human inside the machinery. It is this contrast between the vulnerable, emotionally complex and often youthful human being inside the ominously faceless body armour or power suit and the awesome power she/he wields vicariously that makes for the most important tension in many mecha dramas.’

| A Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s | |

| Donna J. Haraway |

An Ironic Dream of a Common Language for Women in the Integrated Circuit

This essay is an effort to build an ironic political myth faithful to feminism, socialism and materialism. Perhaps more faithful as blasphemy is faithful, than as reverent worship and identification. Blasphemy has always seemed to require taking things very seriously. I know no better stance to adopt from within the secular-religious, evangelical traditions of United States politics, including the politics of socialist feminism. Blasphemy protects one from the moral majority within, while still insisting on the need for community. Blasphemy is not apostasy. Irony is about contradictions that do not resolve into larger wholes, even dialectically, about the tension of holding incompatible things together because both or all are necessary and true. Irony is about humour and serious play. It is also a rhetorical strategy and a political method, one I would like to see more honoured within socialist-feminism. At the centre of my ironic faith, my blasphemy, is the image of the cyborg.

A cyborg is a cybernetic organism, a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction. Social reality is lived social relations, our most important political construction, a world-changing fiction. The international women’s movements have constructed ‘women’s experience’, as well as uncovered or discovered this crucial collective object. This experience is a fiction and fact of the most crucial, political kind. Liberation rests on the construction of the consciousness, the imag-inative apprehension, of oppression, and so of possibility. The cyborg is a matter of fiction and lived experience that changes what counts as women’s experience in the late twentieth century. This is a struggle over life and death, but the boundary between science fiction and social reality is an optical illusion.

Contemporary science fiction is full of cyborgs – creatures simultaneously animal and machine, who populate worlds ambiguously natural and crafted. Modern medicine is also full of cyborgs, of couplings between organism and machine, each conceived as coded devices, in an intimacy and with a power that was not generated in the history of sexuality. Cyborg ‘sex’ restores some of the lovely replicative baroque of ferns and invertebrates (such nice organic prophylactics against heterosexism). Cyborg replication is uncoupled from organic reproduction. Modern production seems like a dream of cyborg colonisation work, a dream that makes the nightmare of Taylorism seem idyllic. And modern war is a cyborg orgy, coded by C3I, command-control-communication-intelligence, an $84 billion item in 1984’s US defence budget. I am making an argument for the cyborg as a fiction mapping our social and bodily reality and as an imaginative resource suggesting some very fruitful couplings. Michael Foucault’s biopolitics is a flaccid premonition of cyborg politics, a very open field.

By the late twentieth century, our time, a mythic time, we are all chimeras, theorised and fabricated hybrids of machine and organism; in short, we are cyborgs. The cyborg is our ontology; it gives us our politics. The cyborg is a condensed image of both imagination and material reality, the two joined centres structuring any possibility of historical transformation. In the traditions of ‘Western’ science and politics – the tradition of racist, male-dominant capitalism; the tradition of progress; the tradition of the appropriation of nature as resource for the productions of culture; the tradition of reproduction of the self from the reflections of the other – the relation between organism and machine has been a border war. The stakes in the border war have been the territories of production, reproduction and imagination. This essay is an argument for pleasure in the confusion of boundaries and for responsibility in their construction. It is also an effort to contribute to socialist-feminist culture and theory in a postmodernist, non-naturalist mode and in the utopian tradition of imagining a world without gender, which is perhaps a world without genesis, but maybe also a world without end.

The cyborg incarnation is outside salvation history. Nor does it mark time on an oedipal calendar, attempting to heal the terrible cleavages of gender in an oral symbiotic utopia or post-oedipal apocalypse. As Zoe Sofoulis argues in her unpublished manuscript on Jacques Lacan, Melanie Klein and nuclear culture, Lacklein, the most terrible and perhaps the most promising monsters in cyborg worlds are embodied in non-oedipal narratives with a different logic of repression, which we need to understand for our survival.

The cyborg is a creature in a post-gender world; it has no truck with bisexuality, pre-oedipal symbiosis, unalienated labour or other seductions to organic wholeness through a final appropriation of all the powers of the parts into a higher unity. In a sense, the cyborg has no origin story in the Western sense – a ‘final’ irony since the cyborg is also the awful apoclyptic telos of the ‘West’s’ escalating dominations of abstract individuation, an ultimate self united at last from all dependency, a man in space. An origin story in the ‘West-ern’, humanist sense depends on the myth of original unity, fullness, bliss and terror, represented by the phallic mother from whom all humans must separate, the task of individual development and of history, the twin potent myths inscribed most powerfully for us in psychoanalysis and Marxism. Hilary Klein has argued that both Marxism and psychoanalysis, in their concepts of labour and of individuation and gender formation, depend on the plot of original unity out of which difference must be produced and enlisted in a drama of escalating domination of woman/nature. The cyborg skips the step of original unity, of identification with nature in the Western sense. This is its illegitimate promise that might lead to subversion of its teleology as star wars.

The cyborg is resolutely committed to partiality, irony, intimacy and perversity. It is oppositional, utopian and completely without innocence. No longer structured by the polarity of public and private, the cyborg defines a technological polis based partly on a revolution of social relations in the oikos, the household. Nature and culture are reworked; the one can no longer be the resource for appropriation or incorporation by the other. The relationships for forming wholes from parts, including those of polarity and hierarchical domination, are at issue in the cyborg world. Unlike the hopes of Frankenstein’s monster, the cyborg does not expect its father to save it through a restoration of the garden; that is, through the fabrication of a heterosexual mate, through its completion in a finished whole, a city and cosmos. The cyborg does not dream of community on the model of the organic family, this time without the oedipal project. The cyborg would not recognise the Garden of Eden; it is not made of mud and cannot dream of returning to dust. Perhaps that is why I want to see if cyborgs can subvert the apocalypse of returning to nuclear dust in the manic compulsion to name the Enemy. Cyborgs are not reverent; they do not remember the cosmos. They are wary of holism, but needy for connection – they seem to have a natural feel for united front politics, but without the vanguard party. The main trouble with cyborgs, of course, is that they are the illegitimate offspring of militarism and patriarchal capitalism, not to mention state socialism. But illegitimate offspring are o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- One: The Wonder of Science Fiction

- Two: Science Fiction’s Disaster Imagination

- Three: Spatial Abyss: The Science Fiction City

- Four: The Origin of Species: Time Travel and the Primal Scene

- Five: Liquid Metal: The Cyborg in Science Fiction

- Six: Imitation of Life: Postmodern Science Fiction

- Seven: Poaching the Universe: Science Fiction Fandom

- Eight: Look to the Skies!: 1950s Science Fiction Invasion Narratives

- Index