![]()

![]()

1

Telling and Not Telling

SOME WRITERS about music video have claimed that videos work primarily as narratives, that they function like parts of movies or television shows. Others have wanted to say that music video is fundamentally antinarrative, a kind of postmodern pastiche that actually gains energy from defying narrative conventions.1 Both of these descriptions reflect technical and aesthetic features of music video that remain worthy of discussion, but they need to be placed in context with techniques drawn from other, particularly musical and visual, realms; we should consider music video’s narrative dimension in relation to its other modes, such as underscoring the music, highlighting the lyrics, and showcasing the star.

Music video presents a range all the way from extremely abstract videos emphasizing color and movement to those that convey a story. But most videos tend to be nonnarrative. An Aristotelian definition—characters with defined personality traits, goals, and a sense of agency encounter obstacles and are changed by them—describes only a small fraction of videos, perhaps one in fifty.2 Still fewer meet the criteria that David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson require in their Film Art: An Introduction: that all of the events we see and hear, plus those we infer or assume to have occurred, can be arranged according to their presumed causal relations, chronological order, duration, frequency, and spatial locations. Even if we have a sense of a music video’s story, we may not feel that we can reconstruct the tale in the manner that Bordwell and Thompson’s criteria demand.3

Music videos do not embody complete narratives or convey finely wrought stories for numerous reasons, some obvious and some less so. Most important, videos follow the song’s form, which tends to be cyclical and episodic rather than sequentially directed. More generally, videos mimic the concerns of pop music, which tend to be a consideration of a topic rather than an enactment of it. If the intent of a music-video image lies in drawing attention to the music—whether to provide commentary upon it or simply to sell it—it makes sense that the image ought not to carry a story or plot in the way that a film might. Otherwise, videomakers would run the risk of our becoming so engaged with the actions of the characters or concerned with impending events that we are pulled outside the realm of the video and become involved with other narrative possibilities. The song would recede into the background, like film music. Music-video image gains from holding back information, confronting the viewer with ambiguous or unclear depictions—if there is a story, it exists only in the dynamic relation between the song and the image as they unfold in time.4

This chapter divides into four sections. It begins with a sketch of the continuum from narrative to nonnarrative videos, tracing some of the familiar forms and providing descriptions of particular examples. Second, it considers why music videos most often do not embody narratives. The penultimate section offers models for understanding nonnarrative modes such as the “process” video, the catalog, and the use of techniques such as contagion. Finally, advice is given for parsing meaning in examples where the message is particularly elusive.

FROM NARRATIVE TO NONNARRATIVE

As a short form with few words, a music video must fulfill competing demands of showcasing the star, reflecting the lyrics, and underscoring the music. If a director wishes to insert a narrative within such confines, she must employ certain techniques and devices. This section examines several narratively oriented videos in order to extract these techniques and devices.

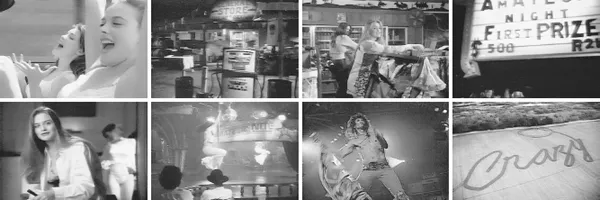

Aerosmith’s “Crazy” is a video that flaunts its narrativity, even if it only creates the appearance of a narrative rather than really delivering one.5 Endowed with some of the proper elements—a beginning and a middle (though not an end)—it has characters who possess volition and encounter obstacles. The video tracks the exploits of two teenage girls as they play hooky, shoplift, enter an amateur strip contest, spend the night in a seedy motel, and then drive off to pick up a hitchhiker and skinny-dip in a lake6 (fig. 1.1).

“Crazy” departs from convention by conveying its tale in the present tense; videos that tell stories most often situate them in the past, stringing together noncontiguous moments by interpolating images of the artist poised in the act of remembering. As in many music videos, the narrative elements are established in the opening images, well before the song begins: a “bad” Catholic girl kicks out a door, revealing her underwear as she escapes from school through a bathroom window. Thus, most of what happens during the video proper—the shoplifting and strip contest—does not represent narrative drive so much as a spinning out of material. Once the characters have committed their greatest transgression—the striptease—there is nowhere else to go. Although a trace of the premise lingers, the rest of the video veers toward a more episodic structure; here, not knowing what might happen, we are taken along for the ride. (At this point, the video begins to operate in a more familiar mode.) Although the supporting characters we encounter in the opening sequences (the gas station owner and his clerk) have some degree of agency and autonomy, characters that appear later (a k.d. lang look-alike and a handsome country bumpkin) are only mannequins—stock figures that elicit less of the viewer’s curiosity.

“Crazy” creates the semblance of a narrative through a clever technique: exploiting the fact that characters lack dialogue. The video alternates between the girls’ lip-sync performances and situations in which they cannot or do not speak. In the former case, the young women sing along as the song blasts over the car radio and mouth the lyrics while stripping in a karaoke talent show; in the latter case, when the girls shoplift, they pantomime to one another to prevent the old man who sits idly in front of the gas station from overhearing. Later in the production, when the two girls prepare for a show, they gaze at one another in mutual affection; here, in the throes of a homoerotic moment, they say nothing because words would be superfluous.

Most often in music video, performance footage of the band has the effect of blunting narrative drive. Here, however, the director, Marty Callner, is able to incorporate incidents involving the women and the band to further the story. The images of Aerosmith, shot so dark that the group is set off from everything else, carry almost no weight, and they almost escape our vision. At one level, when the band appears—as pauses between narrative moments—it becomes irrelevant, like an afterthought; yet at another level the band’s appearance carries deep psychological resonance. The band’s gestures match those of the girls. The lead singer, Steven Tyler, spits, and then so does one of the girls; he throws forward a microphone with attached ribbons, and the other girl tosses her handkerchief into the air. Tyler’s own daughter, Liv, plays the role of one of the rambunctious young women, and in some subtle way, a twinning effect is manifest, with the band imagery suggesting an anxiety lodged in the subconscious of both young woman and singer. For the father, there are thoughts about a child’s actions, as well as a desire to be young again himself, while the daughter dreams of the father who worries about her or of the band member for whom she wishes to become a groupie.7 That characters’ personalities and internal desires feel so palpable makes “Crazy” exceptional; the viewers are able to follow the trajectory of their aims. In most music videos, where music rather than personality is primary, the characters appear too sporadically for the viewer to get a sense of a throughline, or the figures in the frame seem pushed along by the musical flow.

FIGURE 1.1 (A–H) Aerosmith’s “Crazy.” Furthering the narrative through devices appropriate to music video: karaoke, radio singalongs, pantomime, match cuts, signage, quality of light, and the like.

“Crazy” is remarkable for conveying a plot by drawing not from techniques of television programs and film but rather from those of television commercials and movie trailers, both of which are carefully storyboarded. Such techniques work with temporal compression, including precisely choreographed movements of the figures in the frame, and the condensation of what might take three shots in a movie—establishing shot, middle, and close—into a single shot. The mise-en-scène of “Crazy” also borrows from the intertitles of silent film. Throughout the video, signs—the nightclub’s marquee and the gas station’s sundry store—help to show us where we are; to conclude, a tractor plows the word “crazy” onto a field. Other temporal cues reflect specific kinds of daylight: escaping from the schoolyard is linked to the afternoon; stripping in a seedy club to evening; sleeping in the motel to late evening; gazing out of the hotel doorway into the bright sunlight and the seedy hotel’s pool to late morning; picking up a hitchhiker and skinny-dipping to late afternoon. To advance the story, there is a reliance on shots of objects—cars, gas pumps, a photo booth, lipstick, a microphone—and a kind of overgesticulation, or ham acting, that would be out of place in most film genres.

The song does create an ambience that allows the image to diverge from the music and lyrics. Connections might be established between the title and the activities of the characters (the girls are rambunctious, therefore “crazy,” or the father is mad with grief) or between the song’s genre—the road ballad—and the video’s picaresque structure and emphasis on driving, but the narrative world of the video leaves the lyrics far behind. Without an incursion into psychoanalysis, it would be difficult to imagine the song being performed by or addressed to the characters. The effect of this treatment is to make the music seem superfluous: at certain moments of extreme narrative interest, the song as such becomes almost impossible to follow; any effort to concentrate on it in these moments founders, as it might if we were to force our attention onto the soundtrack of a movie during a crucial moment of revelation. Because music videos are not in business to turn our attention away from the song, “Crazy” remains an exception to current practice.8

Of other existing narrative videos to consider, only a handful are fully developed; they usually tell the story in the past tense, and most adopt tragic themes such as murder, adultery, or incest, as in Aerosmith’s “Janie’s Got a Gun,” R. Kelly’s “Down Low,” and Snoop Doggy Dogg’s “Murder Was the Case.” Questions of how the hero will vanquish the villain elicit the viewer’s curiosity, and therefore empathy and involvement—perhaps more than is useful for a music video. When, how far, and in what way the hero will fall can be more thinly sketched and therefore more appropriate to the genre. These videos work well because they are tragedies; they possess a hint of inevitability, as if the outcome were already embedded within the opening of the tape. Often, the hook line helps to focus our attention on the narrative trajectory, telling us what we already know will occur, and leading us inexorably to the main character’s unhappy fate. Accompanied by ominous visual imagery, the lyrics keep us moving forward. Another such example, “Bad Girl,” borrowed from the plot of the 1977 film Looking for Mr. Goodbar, is a video in which Madonna goes out with a number of stray men and is eventually murdered by one. The lyrics “bad girl” as well as iconic imagery let us predict the outcome as the singer passes through a series of tableaux: Madonna’s black dress, encased in dry cleaner’s plastic, looks like the body bag that she will eventually be wrapped in; her cat, who fails to recognize her, hisses like a wild animal, suggesting that she is already a ghost or a figure who bears a curse; and the singer walks through a doorway that looks like the entrance to Hades.

The particularity of epithets like “bad girl” or, even better, of proper names can be emphasized so that the video’s figures take on greater dimensionality, as with the Dixie Chicks’ “Goodbye Earl,” in which the band members hunt down an abusive husband.9 Lyrics can serve the narrative, but in a partial, incomplete manner. The fit between words and other constituent parts of a video—a musical hook, close-ups, a particular object or person in the frame—range from close one-to-one connections to those that are elliptical or disjunctive, and these shift constantly. Although it is possible to separate the lyrics from the image and the music in a limited way, words are largely transformed by image and sound. Because their role varies—lyrics sometimes come to the fore and are sometimes buried deep in the texture—they have a kind of occult quality. Most productions direct our attention to so many different parameters that lyrics do not stand out as a single mode of continuity. For example, in Janet Jackson’s “Love Will Never Do (Without You),” a heterosexual romance is created out of almost nothing—Jackson, several men, a bed sheet, a gargantuan crescent, and a similarly gigantic wheel, all on a desert—and the flimsy plot is quickly derailed. The video opens with Jackson’s maypole dance around a lover, then men and Jackson give chase, suggesting a romance. Jackson’s lyrics and the characters’ shifting facial expressions, as well as a camera that presents different perspectives of the body, can encourage us to piece out a story about the lovers. When Jackson sings, “We’re always falling in and out of love” and “Others said it wouldn’t last,” with a perturbed, slightly weary expression crossing her face, she may be prompting the viewer to consider those off screen—family or friends—who might be too critical. The suggestion of a sexually satisfying relationship is conveyed by the words “like you do-do-do-do,” by the gestures of bending forward with hands on knees and shaking her hips. When she sings, “We’ve always worked it out somehow” and “Love will never do without you,” points a finger, and then the lovers embrace, we assume they have gone through their trials and solidified a union. But can we stake a claim on such an assumption? We have enough time to make a conjecture but not to settle on an interpretation before we move on to the next frame—the narrative structure has already turned in another direction. It becomes fragmentary and volatile: at the bridge and the final chorus, we start seeing more men in swimsuits diving from the sky in a celebratory spectacle.10 All of a sudden, we are really in the Weather Girls’ music video “It’s Raining Men.” To encourage repeated viewing, a video may need tantalizing imagery, or perhaps just additional imagery of another sort. Those who are sensitive to gay iconography will recognize that the imagery is more the director’s fantasy than the star’s.

Strangely, instances when the musician performs while illustrating the lyrics through gestures can encourage the viewer to participate in the narrative in ways that an enactment of the lyrics’ content through a staged scene cannot. (Such scenes—which take on the quality of tableaux—work poorly, in part, because they cannot match the temporal and spatial conditions under which the music was originally composed and recorded.) In his “Little Red Corvette,” Prince’s hands and face show off lyrics like “pocket full of condoms.” The viewer may begin to create a picture for the scene and want to see more of it. But Prince’s bass player is cute: soon one’s attention is diverted elsewhere.

Prodigy’s “Smack My Bitch Up” contains several narrative devices to add to our toolkit on how to construct a music-video narrative. The video creates the sense of a narrative, in part, by presenting the point of view of someone who remains behind the camera. As the camera continually tracks forward, a hand stretches before its lens. Without seeing the body that would ground our sense of this figure, we do not consider the figure’s past and future, aims and desires. The Prodigy song works like techno, bringing elements in and out of a relatively stable mix without establishing sharp sectional divisions. (As such, the videomaker does not need to wrestle with strongly contrasting song sections that might suggest changes of consciousness, activity, or mode of being.) The video’s director combines diagetic sound effects with the prerecorded audio track; these sound effects play against and echo material in the song proper, creating a dense soundscape that rests in neither the song’s world nor the real one. Depicting a single night out, the video unfolds from early evening to sometime at night. The advancing hour is shown through darkening skies and rooms, people who look more and more disheveled, images of clocks, an increasingly shaky camera, and copious ingestion of drugs and alcohol. The drug and alcohol consumption suggests unpredictable shifts in consciousness for which no account need be provided. Most videos that emphasize a story contain an enigmatic ending, and “Smack My Bitch Up” is no different. At the video’s close, a glimpse in a mirror reveals a woman who should be our sexually rapacious, physically abusive protagonist. Attentive viewing shows, however, that the hands before the camera alternate between male an...