eBook - ePub

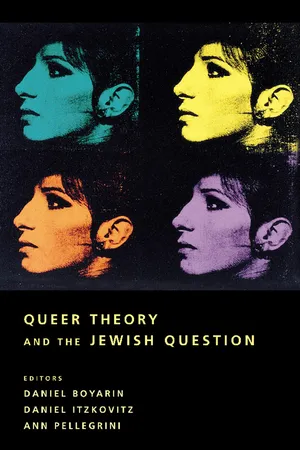

Queer Theory and the Jewish Question

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Queer Theory and the Jewish Question

About this book

The essays in this volume boldly map the historically resonant intersections between Jewishness and queerness, between homophobia and anti-Semitism, and between queer theory and theorizations of Jewishness. With important essays by such well-known figures in queer and gender studies as Judith Butler, Daniel Boyarin, Marjorie Garber, Michael Moon, and Eve Sedgwick, this book is not so much interested in revealing—outing—"queer Jews" as it is in exploring the complex social arrangements and processes through which modern Jewish and homosexual identities emerged as traces of each other during the last two hundred years.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Queer Theory and the Jewish Question by Daniel Boyarin,Daniel Itzkovitz,Ann Pellegrini, Daniel Boyarin, Daniel Itzkovitz, Ann Pellegrini in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Jewish Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Freud, Blüher, and the Secessio Inversa: Männerbünde, Homosexuality, and Freud’s Theory of Cultural Formation

In Totem and Taboo Sigmund Freud endeavored not only to reconstruct the origins of religion but also those of sociopolitical life. Out of threads of British colonial ethnography (Atkinson, Darwin, Lang, Robertson-Smith, Spencer and Gillen, Westermark) Freud manifestly wove together his narrative of the primal horde (Urhorde), the murder of the father by the band of brothers, and its consequences. Upon this evolutionary patchwork Totem and Taboo would read the Oedipus complex, Freud’s algorithm of individual development and desire within the nuclear family, into the origin of human culture.1

This essay argues that the warp and woof that structures Freud’s tapestry of human history is less the confluence of British imperialism and Austrian bourgeois social norms than the entanglement of the gendered, ethnic position of this son of Ostjuden living and writing in the metropole with a particular strand of argument that emerged out of the enthusiasm and Männerphantasien (male fantasies) surrounding Germany’s late nineteenth-century colonial adventures: Hans Blüher’s sexualizing of the ethnographer Heinrich Schurtz’s theories about the foundation and governance of the state by male associations.

Despite devastating critiques by anthropologists of his “just-so story,”2 Freud remained until the last stubbornly convinced of its truth.3 Yet, as the tale traversed his corpus from Totem and Taboo to Moses and Monotheism, Freud would continually tinker with the relationships within the band of brothers, especially with the role played by homosexuality. This essay argues that the changes in Freud’s depiction of homosexuality in his accounts of social origins—the increasingly sharp distinction between homosociality and homosexuality that ultimately culminated in the foreclosure of homosexuality from Freud’s narrative—may be connected with the antisemitic, Völkisch turn of Männerbund theories as well as the racialization of homosexual identities. In the wake of both Blüher’s writings and the loss of Germany’s overseas colonies some postwar German ideologues and ethnographers recolonized their tribal past with homogeneous communities led by cultic bands of male warriors, while others endeavored—far too successfully—to restore those idealized Männerbünde (male bands) in the present. Moreover, Blüher’s work facilitated the public dissemination of a racial typology of homosexualities: the opposition between the healthy inversion characteristic of manly Germanic men and the decadent homosexuality of effeminate Jews.

Overdetermined Origins

Freud’s work, like so many other psychical acts, was overdetermined.4 For Freud this story of beginnings was meant also to signify an end—and indeed ensured one. He wrote to his colleague Karl Abraham that his study would “cut us off cleanly from all Aryan religiousness” associated with the psychoanalytic movement, namely, C. G. Jung.5 It did. Further as some have noted, Freud’s account of the primal horde with its violent and jealous father, with its band of parricidal sons, with its guilt-motivated apotheosis of the paternal imago, may well be said to characterize the psychoanalytic movement.6 Others have taken a different biographical tack and posited Freud’s own ambivalent relationship to his father.7 Still others have also indicated that, rather than tracing the origin of social life, he was backdating the bourgeois family of his own day.8 In this last endeavor Freud joined with the vast majority of ethnographers and social thinkers who viewed kinship ties—and naturalized familial roles—as the crucial form of social organization of tribal societies (Naturvölker).9 They further considered the paternalistic family as both the culmination of those societies’ evolutionary development and the foundation of modern European (Kulturvölker) civil life.

Freud’s exercise in genealogical construction was, however, perhaps less the blind bourgeois tendency to universalize its historical norms10 than the no less unconscious attempt to legitimize both his own position as a postcolonial subject and the institution of socialization and identity formation—the family—that was under siege.11

Postcolonial as Prehistoric

From the time of Freud’s birth to the publication of Totem and Taboo the Jewish population of Vienna increased some twenty-eightfold, from around 6,000 to over 175,000. Waves of Jews from the impoverished provinces of Galicia as well as from Bohemia, Moravia, and Hungary streamed into the imperial capital. Generations who had experienced ghettoization, extensive civil, economic, and vocational restrictions, and a traditional Jewish lifestyle found themselves emancipated citizens with access to secular education (Bildung) as well as the liberal professions and with a Judaism redefined as a private religion rather than a way of life. Yet these assimilation-seeking former inhabitants of the Austro-Hungarian periphery also found themselves still largely engaged in commerce and finance, residing primarily in districts with large Jewish populations and subject to discrimination, prejudice, and antisemitic representations.12

Such was also the trajectory followed by Sigmund Freud. Born in Freiberg, Moravia, he and his family moved to Vienna when he was three. They lived in the district of Leopoldstadt where the vast majority of Jews from the periphery of the Austro-Hungarian Empire had emigrated and where most of the lower-class Viennese Jews such as the Freuds resided; Leopoldstadt figured “the Jewish ghetto in the popular imagination.”13 Despite their tenuous financial situation, his parents ensured that young Sigmund acquired a bourgeois Bildung at gymnasium and university; he then pursued a bourgeois career path, and after marriage resided in a bourgeois district. Although he never denied—denial struck him as “not only undignified but outright foolish”14—and indeed frequently asserted that he was a Jew, Freud realized that he was not in control of the significance of that identification. For many gentiles—and not a few assimilated Jews—“Jew” conveyed the image of the Ostjude, the east European shtetl Jew.15 This identification was in part sustained because a cultural division of labor between Austro-Germans and Jews remained even though the types of employment in bourgeois Vienna had changed.16 Also contributing to this identification was the migration of Ostjuden in and through central Europe, especially after the pogroms of the last decades of the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth. Further, the identification was in part generated by a need to make distinctions. Such differentiation helped create, maintain, and confirm identities that could replace those eroded by the forces of modernization, secularization, and commodification. These identities were forged out of the “natural” differences of nation and race, sex and gender. For Freud’s German readers the space between the inhabitants of the colonizing metropole and those of the colonized periphery created, maintained, and confirmed those essential and hierarchical differences; however, when the colonized entered the metropole and acculturated, the ever precarious identities of the dominant population became more so. To counter the threat, the colonizers imagine the postcolonial subject is merely mimicking them; underlying differences remain and are forever betrayed.17 The Jews, for example, perform their difference; their purported disintegrative intellect and particularity correspond to the presumed disintegrative effect of their presence amid the would-be homogeneous and harmonious dominant culture of the metropole.

Thus throughout his adult life Freud endeavored to distance psychoanalysis from the label “Jewish science,” himself from the linguistic, cultural, and religious accoutrements of his more traditional forebears, and both from the antisemitic representations that littered public—and private—life.18 Like other black faces, Freud wore the white masks of Austro-German bourgeois sexual, gender, and familial identities19—identities that psychoanalytic discourse sustained as much as it provided the narratives and tools to subvert them. And like other postcolonial subjects he internalized the intertwined dominant antisemitic, misogynist, colonialist,20 and homophobic discourses that regularly and traumatically bombarded the Jews (and himself as a Jew) with the opposition between the virile masculine norm and hypervirile cum effeminate other. Freud then reinscribed these images as well as those norms in a hegemonic discourse (the science of psychoanalysis) that in part projected them upon those other Jews (not to be confused with Jewishness per se) as well as women, homosexuals, so-called primitives, the masses, and neurotics, and in part he transformed these representations into universal characteristics.21 Freud’s repudiation of traditional Jewry climaxed with his depiction of the savage Hebrews in Moses and Monotheism. This mass of ex-slaves was unable to renounce its instincts—unlike their later Jewish and bourgeois descendants—and as a consequence murdered their leader Moses.

Faulting the Feminizing Family

In discursively acting out his position within the dominant order, Freud sought to defend not only his place there but that order itself. As Freud was preparing his first major foray into societal origins, the bourgeois family was going largely unchallenged in ethnographic and historical discourses; however, its political significance was being contested throughout central Europe. The contradictory changes that this region experienced going into the prewar years of the twentieth century—industrialization, bureaucratization, urbanization, increasing commodification, women’s emancipation, the decline of liberalism amid the rise of mass politics, as well as the perception of demographic decline, feminization,22 syphilization, and enervation—led to a revolt of sons (and daughters) against the fathers23 and the old order. In c...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Series Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Strange Bedfellows: An Introduction

- Category Crises: The Way of the Cross and the Jewish Star

- Epistemology of the Closet

- Queers Are Like Jews, Aren’t They? Analogy and Alliance Politics

- Freud, Blüher, and the Secessio Inversa: Männerbünde, Homosexuality, and Freud’s Theory of Cultural Formation

- Jew Boys, Queer Boys: Rhetorics of Antisemitism and Homophobia in the Trial of Nathan “Babe” Leopold Jr. and Richard “Dickie” Loeb

- Viva la Diva Citizenship: Post-Zionism and Gay Rights

- Homophobia and the Postcoloniality of the “Jewish Science”

- Messianism, Machismo, and “Marranism”: The Case of Abraham Miguel Cardoso

- The Ghost of Queer Loves Past: Ansky’s “Dybbuk” and the Sexual Transformation of Ashkenaz

- Barbra’s “Funny Girl” Body

- Tragedy and Trash: Yiddish Theater and Queer Theater, Henry James, Charles Ludlam, Ethyl Eichelberger

- You Go, Figure; or, The Rape of a Trope in the “Prioress’s Tale”

- Dickens’s Queer “Jew” and Anglo-Christian Identity Politics: The Contradictions of Victorian Family Values

- Coming Out of the Jewish Closet with Marcel Proust

- Queer Margins: Cocteau, La Belle et la bête, and the Jewish Differend

- Reflections on Germany

- List of Contributors

- Index

- Series List