![]()

CHAPTER ONE

REFUGEE FLIGHT AND ISRAELI POLICIES TOWARD ABANDONED PROPERTY

In 1948, during the first Arab-Israeli war, 726,000 Palestinian Arabs—one-half of the entire Arab population of Palestine—fled or were driven out of their homes in Palestine by Zionist forces. In the process they left behind farmland, tools and animals, homes, factories, bank accounts, and personal property. Israel did not allow the mass repatriation of the refugees and quickly confiscated their property. In this lies the genesis of the refugee property issue.

In recent years much has been written about the massive exodus of Palestinians from their homes but it is beyond the scope of this study to revisit this issue to any detailed extent. The entire issue remains to some extent shrouded in controversy, particularly concerning the causes of the refugees’ flight. Did they voluntarily leave their homes out of fear of the fighting? Were they motivated by fear of Zionist atrocities, such as that at the village of Dayr Yasin outside Jerusalem in April 1948? Or were they expelled by Zionist forces in a campaign of ethnic cleansing? And if this was the case, was this part of a some wider Zionist plot to use the war as an opportunity to rid Palestine of as many of its Palestinian Arab inhabitants as possible, or was it done by local military commanders who wanted to remove potential enemy combatants from behind their lines? It appears that it was a combination of fear of battle, fear of atrocities, and deliberate expulsion that explains why some 726,000 members of an overwhelmingly settled, rural population attached to its homes and fields would abandon them.

Flight of the Refugees

There were distinct waves of Palestinians fleeing their homes, and the refugees can be divided into socioeconomic categories. The so-called “middle class refugees” from the towns and cities constituted the first wave of the refugee exodus, and fled as the fighting between Zionist military organizations and local Palestinians began to escalate shortly after the United Nations partition decision of November 29, 1947. More well-to-do Palestinians in towns either harboring mixed Jewish-Arab populations or that were immediately adjacent to Jewish communities began leaving their homes and property for the safety of surrounding Arab cities like Cairo and Beirut as early as December 1947. That month saw the first movement of urban dwellers from Haifa and Jaffa, followed by an exodus from the Qatamon district in western Jerusalem in January 1948. The sharp escalation of urban fighting in mixed towns by the spring of 1948 prompted further departures, especially following the capture of Haifa by Zionist forces on April 21–22, 1948.

Many of these Palestinian urban dwellers were quite wealthy. They left behind not only luxurious homes replete with expensive furniture and other consumer goods but also shops, warehouses, factories, machinery, and other commercial property. This was in addition to financial assets like bank accounts and valuables such as securities held in safe deposit boxes in banks. Others left behind large citrus groves. Not only were the trees and land temporarily abandoned but so too were irrigation pipes, water pumps, and other capital goods present on the land. None felt that their departure was anything more than a temporary move away from a war zone.

The other sector of the refugee population were the villagers from the countryside. The Hagana, the official militia of the Zionist movement in Palestine, and other Zionist forces began assaulting strategically located Arab locales that they felt constituted a threat to Jewish settlements and supply lines, just as Arab forces attacked Jewish settlements. But in many ways the greatest impetus for the refugee flight came when Zionist forces began to initiate a full-scale offensive in the spring of 1948 against Palestinian villages that lay outside of the area assigned to the so-called Arab state by the UN partition plan. As the fighting spread, Palestinian villagers began to leave an environment replete with mutual violence, atrocities against civilian populations, and fear. Like their urban counterparts, they left behind—temporarily they believed—their homes, farms, farm animals and equipment, and personal property. Generally not possessing bank accounts like their urban counterparts, some buried money in the ground for safekeeping.

By May 1, 1948, 100,000 persons had fled the civil war between Zionist and Palestinian fighters, the latter assisted by a force of foreign Arab volunteers called the Arab Liberation Army. They abandoned ninety villages in the process.1 The large-scale fighting between Israeli and Arab armies that began in mid-May 1948 and eventually lasted until armistice agreements were signed in 1949 created a total of 726,000 Palestinian refugees who fled into Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, the West Bank, and Gaza, as well as Egypt, Iraq, and beyond. Middle- and upper-class Palestinian urbanites moved in with relatives or rented new accommodations. The poor were relegated to refugee camps. The war also triggered the exodus of 30,000 Syrian, Lebanese, Egyptian, Jordanian, and Iraqi Arabs living in Palestine as well.2 In total, these persons left behind a massive amount of moveable and immoveable property, the scope and value of much of which could not be proven either with deeds or by other documents.

By the end of 1948, vast stretches of Palestinian farmland, towns, and villages lay vacant. By the spring of 1949, the untilled fields were covered with wildflowers.3 An American who traveled through Israel in 1951 described the sight of the abandoned towns and villages in this way:

As we went through Israel, the former Arab villages were a broken, distorted mass of mud bricks and falling walls. They were slowly going back into the earth where they came. In the cities, the Arab quarters were being demolished for new streets and modern shops . . . . These old buildings, already partially demolished by the war, were unsanitary and unsafe for habitation. They had to be torn down so that the incoming Jewish refugees would not live in them and so that modern sanitation, water mains, sewers and wide streets could replace them.4

Not all Palestinian refugees were content merely to mourn their lost homes and fields from their new refugee camps. Some began infiltrating through Israeli lines to retrieve property or till their overripe fields, risking being shot in the process, as hundreds were. In at least one case, they chose certain death over the mere risk of death: one distraught Haifa businessman who had left behind his home and business only to end up in a refugee camp in the Jordan Valley near Jericho took his two sons behind their tent quarters one day in November 1948, shot them, and then turned the gun on himself.5

Israeli authorities found themselves in possession of a major economic and demographic windfall in the form of the massive amount of refugee land at their disposal. Exactly how much land the refugees left behind has been the subject of numerous and contradictory studies over the years since 1948. One reason for the difficulties in determining the scope of the property is that British mandatory authorities never completed a thorough cadastral accounting of land in Palestine. Various individuals and official bodies that study the question of refugee property ran against this problem of inadequate sources for documentation. Compounding the difficulty, what records had been created by the British were scattered as a result of the fighting. This entire subject is discussed in great detail later in this study.

Even determining the number of abandoned villages is problematic, in part because the definition of a “village” has varied from source to source. Not all locales from which the refugees came were recognized officially as settlements in the eyes of mandatory authorities, who therefore kept no information on them nor included them on survey maps. Because others were so small or only populated during part of the year they similarly never were considered “true” villages. Defining the term “abandoned” also has proven difficult. Some villages were abandoned totally, while only part of the population fled in others. Such imprecision also has bedeviled attempts to determine how many abandoned villages were razed later by the Israelis.

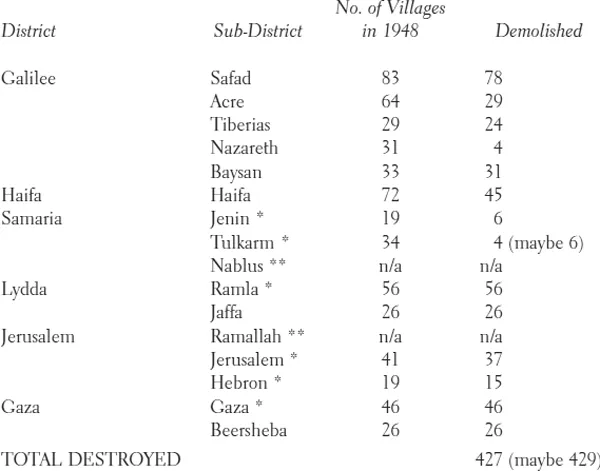

Over the decades several studies have attempted to quantify the number of villages abandoned by Palestinians in 1948. In some cases, researchers also have tried to determine how many of these villages later were destroyed. Most estimates mention between 360 and 429 destroyed villages. The Israeli government cited a figure of 360 abandoned villages to the U.S. State Department in 1949.6 A study from the 1960s by the Palestinian lawyer Sabri Jiryis claimed that 374 abandoned Palestinian communities were destroyed by the Israelis.7 Anti-Zionist Jewish activist Israel Shahak cited a figure of 385 destroyed villages in 1973.8 Recent studies by Israeli and Palestinian scholars also vary, with Israeli estimates once again somewhat lower. Israeli scholar Benny Morris’s detailed study of the question produced a figure of 369 abandoned localities.9 Palestinian geographer Ghazi Falah cited a figure of 418 “depopulated” villages,10 the same number as Palestinian scholar Walid Khalidi’s thorough study of the issue (Falah and Khalidi used some of the same sources, which helps account for the fact that they arrived at the same figure).11 Basheer Nijim and Bishara Muammar claim the highest number of “destroyed” villages: 427 and possibly 429.12

Nijim and Muammar’s work indicates the geographical spread of the destroyed villages they uncovered, and also notes which districts ended up as part of Israel, the West Bank, and/or Gaza (see table 1.1). A more detailed discussion of the various estimates for the scope of the refugees’ land appears later in this study.

The question of to what degree Jewish authorities deliberately expelled Palestinians is a hotly contested one.13 For many historians of the Arab-Israeli conflict, the issue comes down to whether Zionist authorities ordered the deliberate expulsion of the Palestinians according to a master plan of ethnic cleansing. It is beyond dispute that some expulsions occurred as it is that, even before the fighting began, various figures in the Zionist movement were actively investigating the idea of what they euphemistically called “transferring” the Palestinians out of the country. One such person was Yosef Weitz of the Jewish National Fund [Heb.: Keren Kayemet le-Yisra’el]. Weitz was born in Russia in 1890 and immigrated to Ottoman Palestine in 1908. He began working for the Jewish National Fund (JNF) in 1918. The JNF was established by the World Zionist Organization [Heb.: ha-Histadrut ha-Tsiyonit; later, ha-Histadrut ha-Tsiyonit ha-‘Olamit] in December 1901 to acquire land in Ottoman Syria for the establishment of a Jewish state. It acquired its first land in Palestine in 1904. In 1907, the JNF was incorporated in London as the Jewish National Fund, Ltd., although its offices were located on the continent and moved several times over the decades. Starting in 1932, Weitz had risen to serve as the director of the JNF’s Land Development Division. He was also involved in the establishment of the Histadrut, the all-encompassing Zionist labor federation.

TABLE 1.1 Palestinian Villages Destroyed in 1948, by Mandatory District

* = subdistricts that ended up both in Israel and the West Bank and/or Gaza

** = subdistricts that ended up in the West Bank only

Source: Basheer K. Nijim, ed., with Bishara Muammar, Toward the De-Arabization of Palestine/Israel 1945–1977. Published under the Auspices of The Jerusalem Fund for Education and Community Development (Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company, 1984).

By 1948, Weitz was one of the most knowledgeable Zionist land officials in the country. While he was not a leading political figure in the Zionist movement but rather a JNF bureaucrat, he had considerable access to such top officials and made his views known. He was indefatigable in his zeal for pursuing the ...