eBook - ePub

Available until 27 Jan |Learn more

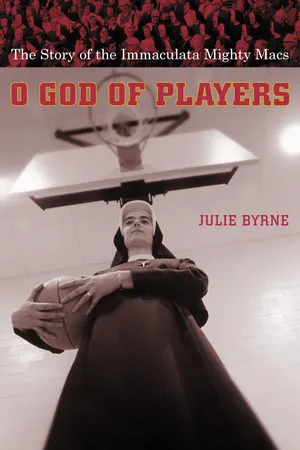

O God of Players

The Story of the Immaculata Mighty Macs

This book is available to read until 27th January, 2026

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 27 Jan |Learn more

About this book

Between 1972 and 1974, the Mighty Macs of Immaculata College—a small Catholic women's school outside Philadelphia—made history by winning the first three women's national college basketball championships ever played. A true Cinderella team, this unlikely fifteenth-seeded squad triumphed against enormous odds and four powerhouse state teams to secure the championship title and capture the imaginations of fans and sportswriters across the country. But while they were making a significant contribution to legitimizing women's sports in America, the Mighty Macs were also challenging the traditional roles and obligations that circumscribed their Catholic schoolgirl lives. In this vivid account of Immaculata basketball, Julie Byrne goes beyond the fame to explore these young women's unusual lives, their rare opportunities and pleasures, their religious culture, and the broader ideas of womanhood they inspired and helped redefine.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access O God of Players by Julie Byrne in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

ReligionCHAPTER 1

MAKING THE TEAM, MAKING IDENTITY

For the 1940 season, team tryouts were scheduled for a December afternoon shortly before the Christmas holidays. As late classes ended and stragglers hurried to the gymnasium in Villa Maria Hall’s basement, they were surprised to find more than fifty other girls—about a quarter of the entire student body—already bouncing heavy leather balls and practicing favorite shots. Only in its second season, the team attracted a multitude of Immaculatans enamored of basketball. Many of them came from local Catholic high school squads and wanted to keep playing. Some had missed making their high school teams and saw the fledgling college varsity as a second chance. Still others, Catholic girls from New Jersey, northern Pennsylvania, and other states, had never touched a basketball in their lives. But they found themselves trying out anyway, drawn by buzz and curiosity and hope.1

Most Immaculatans in the gym, however, had already decided there was something special and wonderful about basketball. Most had already spent countless hours honing their games. There were lots of fun things about the sport. You ran the court, goofed around with teammates, went on road trips, and played to crowds. But at tryouts girls were expressing a more fundamental desire: simply to make the team. To earn the right to be called a basketball player. To be a basketball player.

Sister Marita David “Toddy” Kirsch, who made the Immaculata team at 1944 tryouts, liked being a basketball player. “I was thrilled, to say the least,” she said. A strong wiry forward from Wayne, Pennsylvania, a few miles from Immaculata, Toddy was typical of Immaculata players who arrived on campus already deeply in love with the game. Basketball was her identity, the core of her being, the time of day she felt most fully herself. Fifty-four years later, Sister Marita David told me about her playing days as we sat in a seminar room of Immaculata’s Gabriele Library. A college librarian, she was still small and tough, and her blue eyes darted as she talked, as if looking for the open shooter. She told me she had had “eyes for basketball” ever since sixth grade, when her parents gave her a basketball for Christmas—instead of the football equipment she requested. “After that, I was gone,” she said. “Out. Wherever the basket was, that’s where I was.”

Then she said, “I mean as much as within reason, regarding other things I had to do at home.” Basketball was Toddy’s identity, but her identity was, of course, relative to parents, siblings, friends, and the wider community. As the middle child in a Catholic family of seven siblings, she helped her mother with childcare, cooking, and cleaning. Such chores were routinely expected of daughters, and Sister Marita David said she didn’t mind. But she did discover that basketball got her out of the house a little bit more. Furthermore, sports meant time with her father. The brothers did chores with their dad, but the girls’ hours with him consisted mostly of fun and games. Mr. Kirsch had played basketball and football at Villanova, and with him she and her siblings “did… most everything sportswise that you could do,” from basketball and ice-skating to tennis and baseball. “We always had a basket in the backyard so we did do that together, played H-O-R-S-E,” she remembered. “Dad would play with us.”

Basketball was a source of identification with her dad, and also with boys. If her father was at work, Toddy shot around or picked up games with siblings and friends. Usually, girls outside her family did not play. “The girls that were in my neighborhood didn’t seem to really want to get into the sports that much,” she remembered. Athletic interest marked a difference between Toddy and other, mostly Catholic neighborhood girls. “I don’t know for sure what some of them did when they were at home in the house, whether they just did house things,” Sister Marita David said. “There were some things that we could do together, but… I couldn’t find them to do any of the sports that I wanted to do, so I just went and did them.”

Basketball anchored her college experience, too. By that time, she said, it was the most important thing in her life. “There was no way I was not going to go out for the team,” she said. “I was going to give this a shot because I really wanted to do it.” Sister Marita David told me proudly that she “made the first team, the first year.” Looking forward all day to practices, she could barely contain her excitement before games. As a sophomore, Toddy helped the Mackies steal the Mythical City Championship from Temple. Eventually, the grade-schooler who had found she’d rather shoot hoops than play house discovered she liked playing basketball more than taking classes. To spare her parents wasted expense, Toddy dropped out after her sophomore year. But she remained a basketball player long after she stopped being a student, joining a team sponsored by her parish and coaching Catholic school teams. Even when she felt called to join the Immaculate Heart order, basketball stayed with her. Sister Marita David said she endured the grunt work of the novitiate by remembering excruciating hours devoted to dribbling, jumping, and shooting. “Well, if I can play basketball that hard, then I can scrub this floor,” she told herself. Proving herself to a new community, Sister Marita David thought of herself as a dedicated basketball player so she could become a faithful nun.2

Among Immaculatans assembled for basketball tryouts any given year, Toddy was not unusual in putting the game at the head of life. For most former players to whom I spoke, being a basketball player was not just another extracurricular pastime, not just another identity among many. It was a central activity by which, at least for a period in their lives, they identified to themselves and others who they were. Of course, Immaculata players were also Catholics, daughters, sisters, students, friends, and girlfriends, and they did not feel the need to separate out different strands of their composite identities. Certainly, most of them heard more at home about chores, more at church about God, and more at school about studies than about basketball. But in their own minds, they said, basketball had a way of pushing itself to top priority.

How did basketball get so important? Surely, some hopefuls had developed a taste for fame, fresh from high school games played in packed gyms. But most Immaculatans didn’t try out for glory. Through the sixties, women’s college basketball played second fiddle to the high school girls’, and only in the seventies did Immaculata’s teams command huge venues full of spectators. Some years, the Mackies barely pulled off a winning season. Some team members didn’t get much playing time. So making the team mostly involved going to practice day after day, stealing time from studies and social life, and getting to bed late. But Immaculata players didn’t seem to care. They just wanted to make the team. They just wanted to be basketball players.

If it wasn’t about fame and glory, then why? I asked former players that question and got many different explanations. That why goes to the heart of basketball’s pleasures for traditional Philadelphia Catholic girls. And as I tell their story, I pursue their answers—answers about class and community, spirituality and physicality. But before Immaculata players explained the whys, they took for granted that just being a team member was a pleasure in itself. It was a pleasurable identity. Basketball was fun, Marian Collins Mullahy ’54 said, “but, you know what, it was also my identity… Marian Collins played basketball.” It made them special with regard to fellow Catholics, other girls, and new possibilities. It marked them within the Philadelphia Catholic world, a subculture devoted to the girls’ game but also vigilant of overall gender formation. It got them affirmation from Catholics who supported girls’ basketball and negative attention from those who didn’t. Before any other reason, Immaculata team members liked the game because as basketball players they identified who they wanted to be—and who they did not want to be—as young Catholic women. For Immaculata hopefuls, making the team also meant making identity.3

Making the Team

It was because identity was at stake that basketball tryouts became an occasion of paramount importance. Of course, Immaculata basketball players had the chance to “make identity” only to a limited degree. The identity of young Catholic women, as with all social identity, was largely given. For the most part, young women who tried out for Immaculata basketball were traditional Catholic girls who conformed to the expectations of parents, teachers, and religious authorities. But basketball was a specialized activity. Though overwhelmingly endorsed in Catholic Philadelphia, it still fell outside the scope of given identity for Catholic girls. And while almost every parish and school eventually sponsored a girls’ basketball team, only a lucky few made the roster each season. As such, basketball opened possibilities for new relations with self and others—and for new, even if partial or temporary, identities within Catholicism. For Immaculatans, the chance to be basketball players offered an opportunity to fashion, in some small way, fresh senses of Catholic girlhood. And the fresh girlhood that basketball seemed to promise could be heady. For many Immaculata players, it was as if basketball became the yardstick by which they gauged themselves, as much as by traditional standards of family, school, and church. At tryouts, they gambled a chunk of self-esteem in hopes of measuring up. Whatever the substance of the new identities players imagined for themselves, they felt team membership could help give it to them.

At Immaculata, tryouts perennially drew more basketball devotees than coaches needed for two squads, varsity and junior varsity. To some extent, though, the popularity of the sport at Immaculata fluctuated with its success. In the late sixties, during the college’s only losing seasons, tryouts drew the fewest aspirants, just thirty or so girls out of a student body of nearly eight hundred. In those years, “anyone who went to practice… was on the team and got to play,” recalled Patricia LaRocco ’71. But in the fall of 1974, after three championships, over 350 girls—a little less than half the student body—showed up for the first practice, including dozens of national-caliber players from all parts of the country.4

Still, whether the hopefuls numbered thirty or three hundred, they all came to tryouts for the same reason—the chance to be part of the team. Years later, regardless of season records or personal accomplishments, some players said their happiest memory of basketball was “joy at being part of a wonderful group” or just simply “being part of the team.” For that reason, they said over and over, tryouts were gravely important. After playing high school ball, said Ann McSorley Lukens ’53, she “desperately wanted to be picked for the team.” If players worried about their chances, tryouts definitely merited prayer. “I prayed hard to make the varsity team,” recalled a player from the class of ’52. And when Margaret Klopfle Devinney ’62 tried out, she planted her own special cheering section in the bleachers. “I was an experienced player, but others were much better than I,” she wrote. “But I had fine friends who cheered very loudly whenever I did the least positive thing (especially when the coach was not paying particular attention to me)… so the coach was at least subconsciously influenced with the sound of my name shouted so often.” After tryouts, players waited with hearts pounding to hear who had made the cut. If their gamble had paid off, wracked nerves gave way to relief and happiness. Ann remembered feeling “elated that I was part of this group.”5

When a young woman made the Immaculata team, she had already decided that the kind of girl she wanted to be and the kinds of girls she wanted as friends played basketball. “You made friends,… almost for life,” said a class of 1945 player. “Because they were the same way as you—they understood, you know?” Often, friends had introduced them to the sport. A 1950s player made her high school basketball team after trying out on a girlfriend’s whim. “She said, ‘Come on, we’re both tall, let’s go,’” she remembered. Basketball and the friends who played it reinforced each other. When it was time to choose a college, players said, they often heard about Immaculata by word of mouth from former teammates and other hoop acquaintances. They would visit a friend who played at Immaculata, attend a basketball practice, and like what they saw. Margaret Mary “Meg” Kenny Kean ’58 enrolled at Immaculata because she was “so impressed with the team members.” Mary Frank McCormick ’50 chose Immaculata because former players on her parish team already went there.6

Trying out for the team as freshmen, players found some welcome familiarity in the scary new world of college. “We had known one another from playing locally in the area,” recalled Evie Adams Atkinson ’46. “So, we sort of felt as though we knew somebody. Even though we were in a strange college, there were other people that we knew. And we had a common bond.” From there, she said, the new teammates only got more tightly attached. They had played against each other, she said, “but it was different when you played together…. Oh, it was fun.” Many years later, Janet Young Eline ’74 also felt reassured to meet others like her in the gym. “At tryouts I met other players who were also captains or outstanding players at their high schools.”7

Throughout the years, Immaculatans remembered teammates as “special friends,” “best friends,” and “my best friends in the whole world.” Spending time together, enduring hard practices, pulling together to win, and sharing common interests, Immaculata basketball players built “unmatched” relationships. “You never thought, like, oh, another day at practice,” said Helen Frank Dunigan ’56. “You went because it was a great time, [you] had fun.” Those relationships extended off the court, too. Teammates grew to know each others’ families, interests, and love lives. These friendships were half the fun of the sport. “You’d relive the basketball game to begin with, if you played that night,” said Evie Adams Atkinson ’46. “Then, of course, you talk about studies and you talk about who you were dating and who was going to go to the prom. You know, it was not all basketball, nor was it all studies. It kind of all intermeshed.”8

If players did not have full-fledged friendships with each teammate, still the bonds of basketball could surpass many friendships, forged not only during long hours on the court but also in the “sense of importance of being a select few.” They were the ones who got to wear what their campus newspaper called “the coveted blue and white uniforms.” They got perks. “All the perks,” said Marian Collins Mullahy ’54. “You couldn’t beat ’em. First of all, you missed about half a day at school, so you didn’t even have to prepare for those classes…. It doesn’t sound like anything now, but at my time, it was extraordinary.” Out of class early, players took “pride” in walking with teammates and “wearing the I.C. jacket”—for most years, a thin blue satin coat with the white letters I and C intertwined on the front left. “People… had a lot of respect when you wore your jacket,” said a player who graduated in 1945. “We wore them everywhere we went.” Strolling together, wearing the gear, or just hanging out after practice, players felt a “sense of belonging” with this “wonderful group of girl athletes.” Altogether, team members felt they were “different” and liked it. What exactly was different? Maybe they got to run outdoors and skimp house duties, as Sister Marita David said. Maybe they were more dynamic or more confident than other girls, others suggested. “My friends that were on teams never stopped,” Marian said. “We liked who we were and what we were doing.” However they defined it, the team was a pleasure, a small collective of female élan, a tight crew whose pride competed with that of school, family, and church.9

Of course, tryouts meant that some made the team and some did not. The competitive preseason conferred on new team members not only the prize of being basketball players but also the affirmation of beating out other hopefuls. Immediately after tryouts, the game marked both commonality with new teammates and distinction from unluckier attendees. And throughout the season, the elite crew of Immaculata players also used basketball to identify with—or distinguish themselves from—others in their Catholic world. For them, the community’s significant categories included not only women and men, priests and parents, students and teachers but also—according to their take on basketball—fans and foes.

Girls’ Basketball Fans

The Catholic community’s basketball fans gathered from all...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Series Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Abbreviations

- Note on Notation

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Philadelphia Hoop and Catholic Fun

- Chapter 1. Making the Team,Making Identity

- Chapter 2. Practicing Basketball, Practicing Class

- Chapter 3. Bodies in Basketball

- Chapter 4. Praying for the Team

- Chapter 5. Ladies of the Court

- Chapter 6. Championships and Community

- Postscript: Immaculata Basketball and U.S. Religious History

- Appendix A: Immaculata College Basketball Survey

- Appendix B: Surveys, Interviews, Correspondence, and Unpublished Memoirs

- Notes

- References

- Index