![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE AUDIENCE MARKETPLACE

The audience marketplace is a vital component of the U.S. economy. In 2001 the investment-banking firm of Veronis, Suhler, and Associates estimated that the media industries had earned more than $190 billion over the previous year through the sale of their audiences to advertisers. Before I examine the dynamics of the audience marketplace, a review of the key participants in this marketplace, their primary activities, and their relationships to one another is in order. This overview will help place later discussions about the nature of the audience product and the effects of changes in the predictability, measurement, and valuation of the audience product in the proper institutional context.

COMPONENTS OF THE AUDIENCE MARKETPLACE

The audience marketplace is comprised of four primary participants. In the first category are the media organizations—which I define as any type of media content provider that derives revenue from the sale of audiences—that provide the content designed to attract audiences. Thus this category includes, among others, television and radio stations and networks, cable systems and networks, Web sites and Internet service providers (ISPs), as well as newspaper and magazine publishers. The United States has approximately 1,300 VHF and UHF commercial television stations, 11,200 commercial radio stations, 280 cable networks, 10,000 cable systems, 11,800 magazines, 1,400 daily newspapers, 8,000 foreign-language and nondaily newspapers, and thousands of Web sites that derive at least part of their revenue from the sale of audiences to advertisers (Compaine and Gomery 2000; FCC 2002b; National Cable 2002). Thus advertisers have a nearly overwhelming number of outlets by which to reach audiences.

These raw numbers do not, however, provide an accurate picture of the level of competition in the audience marketplace. Like all markets for goods and services, the audience market is differentiated according to geographic markets and product markets. From a geographic standpoint, some media organizations (such as broadcast and cable networks) provide advertisers with access to a nationwide audience. Other media organizations, such as an individual radio station or metropolitan newspaper, generally provide access to a much more local audience. Reflecting this market segmentation, Arbitron has organized its radio audience measurement reports according to 286 distinct radio markets within the United States. Similarly, Nielsen Media Research has delineated 210 distinct television markets within the United States. Local television or radio stations do not often compete for the same advertising dollars as the broadcast and cable networks. Thus it is important to recognize that the audience market is not only national (and increasingly global) but that smaller, geographically defined local audience markets number in the hundreds.

Markets are defined not only geographically but also in terms of product characteristics. From an advertiser’s standpoint one media outlet’s audience is not necessarily a reasonable substitute for another media outlet’s audience. Advertisers seek specific characteristics in the audiences that they try to reach: age, gender, income, and a host of other distinguishing factors (see chapter 4). Thus for most advertisers the audience for the Nickelodeon cable network (which targets children) is not likely to be an acceptable substitute for the audience for NBC’s Friends (which targets young adults).

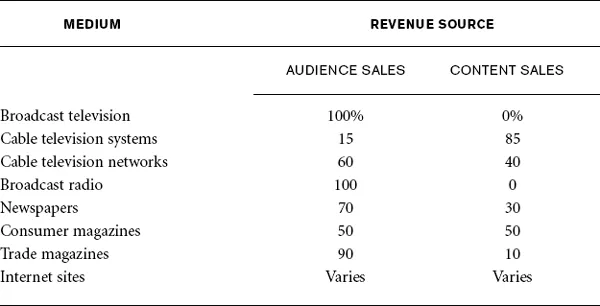

Media organizations differ in the extent to which their viability depends upon the sale of audiences to advertisers. In many instances they supplement revenue from the sale of audiences to advertisers with revenue from the sale of content to audiences. The revenue breakdowns for each major advertiser-supported medium appear in table 1.1. As the table shows, free over-the-air broadcast radio and television derive basically all their revenue from the sale of audiences to advertisers. In contrast, cable television systems rely heavily upon subscriber fees. Subscriber fees account for roughly 85 percent of cable systems’ revenues, with advertising revenues comprising only about 15 percent. Cable networks, on the other hand, derive, on average, 60 percent of their revenue from the sale of audiences to advertisers and 40 percent from the sale of their content to cable and direct broadcast satellite systems. Consumer and trade magazines operate under quite different economic models.1 Consumer magazines operate at a roughly 50–50 split between the sale of audiences and the sale of content. Trade magazines, on the other hand, derive roughly 90 percent of their revenues from the sale of audiences to advertisers. Newspapers receive roughly 70 percent of their revenues from the sale of audiences to advertisers and 30 percent from the sale of their content. In most cases the price that consumers pay for a daily newspaper does not even cover the costs of the paper and ink. These data provide an indication of how different media have taken different strategic paths in navigating the dual-product marketplace that characterizes the media industries.

TABLE 1.1 Revenue Breakdowns for Advertiser-Supported Media

Sources: National Cable 2002; Compaine and Gomery 2000; Veronis, Suhler, and Associates 2001.

Within each component of the media industry, many individual media outlets fall under the broad umbrella ownership of a few large, diversified media corporations (Bagdikian 1997; Compaine and Gomery 2000). Most of the largest media firms have expanded their reach across a variety of media technologies, suggesting that they realize certain economies by providing advertisers with access to audiences across a range of media types.2 Although the issue of the growth of media conglomerates is largely beyond the scope of this book, this phenomenon is relevant to the extent that, among the primary rationales for media firms’ efforts to expand their holdings is their desire to bring greater efficiencies to the sale of audiences to advertisers and to be able to offer advertisers what essentially amounts to one-stop shopping for all their audience needs.3 The merger of CBS and Viacom was deemed a particularly shrewd strategic maneuver in this regard. The combined holdings of CBS-Viacom range from the Nickelodeon cable channel, with its predominantly preteen audience, to MTV, with its teenage and young adult audience, to CBS, with its predominantly over-50 audience. CBS/Viacom is using this combination of media properties to provide what its executives have called “cradle-to-grave” marketing opportunities to advertisers.4

In the second key category of participants in the audience marketplace are the audience measurement organizations, which provide quantitative data on audience attention. Both advertisers and media organizations purchase these data, which function essentially as the coin of exchange in the audience marketplace. Although audience measurement typically is discussed within the context of analyzing individual segments of the media industry, the measurement of media audiences is a significant industry in its own right, with its own distinguishing characteristics, historical progression, and enduring controversies (Beville 1988; Buzzard 1990; P. Miller 1994). Although audience measurement originated internally among media organizations, third-party firms long have dominated the process because of the obvious potential for bias if audience transactions were based upon data supplied by the media organizations (Beville 1988). Thus it is important to regard audience measurement firms as a separate participant within the audience marketplace.

Across all the advertiser-supported media are a number of firms that provide either specialized or comprehensive data about the distribution of consumer attention to various content options. These data can range from standardized syndicated reports that provide a broad overview of how audiences are distributing themselves across the entire range of content options to highly specialized, commissioned studies of the audiences for individual media products (P. Miller 1994). One defining characteristic of the audience measurement industry is that, although a number of different firms provide statistical representations of media audiences, only one firm tends to dominate the distribution of comprehensive audience data for each media technology. Thus Arbitron is the primary source for radio audience data, Nielsen Media Research is the sole source for comprehensive television audience data, and the primary sources for detailed magazine audience measurement are Simmons and Mediamark Research, Inc., with general circulation data provided by the Audit Bureau of Circulations, which also provides circulation figures for the newspaper industry. The development of the Internet audience measurement industry is following historical precedent, in that two major competitors remain from the dozens of measurement firms that initially offered this service: comScore Media Metrix and Nielsen Net-Ratings. As Jim Spaeth, president of the Advertising Research Foundation, has noted, “There is a tendency toward monopolization in ratings services” (Thompson and Lake 2001:55).

The primary explanation for this phenomenon is that audience data function as the coin of exchange within the audience marketplace. Thus both the buyers and sellers of audiences subscribe to audience measurement services in order to be fully informed of the nature of the product that they are buying and selling. The introduction of a second measurement service essentially represents a second currency. New entrants in the field generally use measurement techniques or technologies that differ in either minor or significant ways from the incumbent’s. Such deviations are a natural and logical effort by firms to differentiate themselves from the competition. The measurement techniques and technologies of the new competitor may even be of a substantially higher quality than those used by the incumbent. In any case, these methodological differences inevitably result in audience data that differ significantly from the data provided by the incumbent. Thus buyers and sellers in the audience marketplace are faced with two different accounts of, for example, how many people watched last night’s episode of CSI or of how many people listened to the local classical music station. In such a situation participants in the audience marketplace naturally will seize upon those numbers that best reflect their best interests. When CBS is negotiating advertising rates, it is likely to rely upon the data from the service that shows a higher rating for CSI, while advertisers are likely to rely upon the service that shows a lower rating.

Thus the existence of competing measurement services substantially complicates the process of buying and selling audiences, as it introduces additional uncertainty into the nature of the product being bought and sold and introduces an additional negotiation factor. Marketplace participants generally see these additional complications as problematic because they slow down or discourage the process of buying and selling a product that is highly perishable.

Also important is that, with two competing currencies on the market, marketplace participants often must subscribe to both (Beville 1988). The obvious inefficiency here is that buyers and sellers of audiences are paying twice for depictions of the same product. The costs of this redundancy, combined with how the existence of multiple measurement systems complicates negotiation in the buying and selling of audiences, mean that both advertisers and media organizations tend to favor (or at least accept) the existence of a single audience measurement system for each medium. Thus competing measurement systems historically have found it difficult to establish and maintain a foothold against an entrenched incumbent (Beville 1988). For example, Arbitron (among others) attempted to compete with Nielsen in providing data about television audiences (see Buzzard 1990). In 1993, however, Arbitron abandoned its television operation because it had been unable to capture sufficient market share from Nielsen.

For these same reasons many analysts of the Internet industry saw the consolidation that has taken place in Internet audience measurement as inevitable (Thompson and Lake 2001). Ultimately, as the media researcher Erwin Ephron has noted, “This is not a business that lends itself to competition. You don’t want more than one currency” (Bachman 2000a:7). This sentiment—and the trade-offs that it entails—is reflected in an analysis of the consolidation of Internet audience measurement: “For customers, there could be a silver lining. . . . Having one fewer ratings company may not result in the most accurate figures, but it will at least reduce confusion” (Thompson and Lake 2001:55).

As this statement suggests, these periods of competition lead to data of higher quality (Beville 1988; Buzzard 1990), just as competition in any product market typically results in higher-quality products at lower prices. As Rubens (1984) shows, competition between Nielsen and Arbitron led to a rapid expansion in the number of markets in which they deployed set-top meters. Similarly, competition from Audits of Great Britain in the 1980s accelerated the deployment of people meters (Rubens 1984).

Thus the audience marketplace illustrates two countervailing forces. On the one hand, the desire for better quality in audience measurement persists, because better measurement means a higher-quality audience product (something generally desired by both advertisers and media organizations). On the other hand, the audience marketplace wants a single parsimonious currency, something achievable only when the provider of audience data is a monopoly.

The third key participant in the audience marketplace is the advertisers. Advertisers are the consumers of the audience product. I am using the term advertisers broadly here to encompass both the providers of products and services seeking an audience of consumers to purchase their offerings, as well as the advertising agencies, media planners, and media buyers who act on their behalf to create advertising messages and place them within various media products (see Silk and Berndt 1993, 1994).

Table 1.2 presents the ten largest advertisers in the United States in 2000, along with the total amount that they spent on advertising in that year. As this table shows, these top ten advertisers represent more than $22 billion worth of advertising. Given that annual media advertising revenues exceed roughly $150 billion, clearly no one advertiser has monopsony power in the market for audiences. Further reinforcing this point is that the top one hundred advertisers represented only 48.3 percent of total advertising expenditures in 2000 (Endicott 2001). Thus although concentration levels among the sellers of audiences are of long-standing concern (see Napoli 2001b; Stucke and Grunes 2001), historically, concentration levels among the buyers of audiences have been of comparatively little concern.5

TABLE 1.2 Ten Largest Advertisers in the United States (By Expenditures).

| CORPORATION | 2000 ADVERTISING EXPENDITURES |

| 1. General Motors Corp. | $3,934.80 |

| 2. Phillip Morris Cos. | $2,602.90 |

| 3. Procter & Gamble Co. | $2,363.50 |

| 4. Ford Motor Co. | $2,345.20 |

| 5. Pfizer | $2,265.30 |

| 6. PepsiCo | $2,100.70 |

| 7. DaimlerChrysler | $1,984.00 |

| 8. AOL Time Warner | $1,770.10 |

| 9. Walt Disney Co. | $1,757.50 |

| 10. Verizon Communications | $1,612.90 |

| Total: $22,736.90 |

Source: Endicott (2001:52).

Finally and perhaps most important are the consumers of advertised products and services, whose attention represents the foundation upon which the entire audience marketplace is based. I use the term consumers here as a reminder that the advertisers who drive the audience market are fundamentally concerned with reaching potential purchasers of the products and services that they have to offer. The central underlying assumption in the audience marketplace is that the audience product provides a meaningful representation of consumer attention to advertising messages. This attention should then influence consumers’ purchasing decisions (see M. Ehrlich and Fisher 1982).

Certainly, the use of the term consumers here, instead of audiences or potential audiences, reflects a fairly limited view of the processes by which individuals interact with media. As many analysts of media audiences have pointed out, being part of a media audience and consuming media products are complex sociocultural phenomena containing numerous layers of meaning and multiple points of analysis (Ang 1991; Butsch 2000; Chang 1987; Moores 1993; Webster 1998). Audience consumption of media content certainly can be analyzed at levels that run deeper than mere exposure to content and its integrated advertising messages, addressing issues such as audience appreciation or interpretation of media content (e.g., Danaher and Lawrie 1998; Gunter and Wober 1992; Lindlof 1988). Indeed, this analysis of the audience marketplace, and the role that consumers/audience members play in this marketplace, takes as a given the frequent criticism that media organizations, advertisers, and measurement firms operate with a limited conceptualization of what it means to be part of a media audience (e.g., Ang 1991; Mosco and Kaye 2000). Much of what we know, or want to know, about the nature of—and processes associated with—media audiences is of no immediate concern to these marketplace participants.

However, given that the focus here is on the role and function of audiences within the economics of media industries, the analytical perspective toward media audiences narrows considerably. Indeed, from a stric...