![]()

CHAPTER 1

Foundations of the Universe

The more the universe seems comprehensible, the more it also seems pointless.

—STEVEN WEINBERG, The First Three Minutes (1993)

The universe was not pregnant with life nor the biosphere with man.

—JACQUES MONOD, Chance and Necessity (1971)

These two great scientists, Weinberg the physicist, Nobel Prize 1979, and Monod the biologist, Nobel Prize 1965, seem to speak in concert: there is no imperative for the universe to exist, nor is there one for the existence of life, including that of humans. Weinberg goes on to say, “But if there is no solace in the fruits of our research, there is at least some consolation in the research itself,” and Monod, writing about the transcendence of ideas and knowledge over ignorance, announces, “[Man’s] destiny is nowhere spelled out, nor is his duty. The kingdom above or the darkness below: it is for him to choose.”

These two men lay bare the stupefying yet exhilarating recognition that there is no design in the universe. At the same time, there is a great sense of freedom and responsibility that this thrusts upon us. There is a human imperative, but it does not originate outside of us; we have created this imperative ourselves. We must now complete our own destiny: our self-imposed search for the origin of the universe and that of life. These are the two deepest questions that science can ask and perhaps answer. Let us now start our quest, from the very beginning, and study the foundation upon which our understanding of the universe is built.

For thousands of years humans have gazed at the night sky, the Sun, the planets, the surface of Earth, the plants and animals, and themselves. They have tried to make sense of what they saw and constructed explanations to justify the existence of the natural world. Most of these explanations have not passed the test of time. Today a set of interlocking scientific theories exists that provide tentative answers to the origin of the universe and that of matter. These theories result from the melding of relativity and quantum physics into cosmology. But to understand the current model for the creation of the universe, one must first know what the universe contains and understand the physical theories that made this model, the Big Bang, possible.

WHAT IS IN THE UNIVERSE?

As Carl Sagan, the famous American astronomer and science popularizer once suggested, only the word billions can give us any idea of what the universe is all about. The cosmos is very large. Some wealthy people may own a few billion dollars, but even that number, as high as it may seem, is nothing in comparison to the number of stars in the known universe. In mathematical notation, 1 billion is 109, 1 followed by nine zeros. The universe contains 1011 (100 billion) galaxies, groups of stars, and each galaxy contains on average 1011 stars, for a grand total of 1022 stars. Therefore the estimated number of stars in the observable universe is 1013 times bigger than the number of one-dollar bills in a billionaire’s wallet. This means that if each dollar bill were equal to one single star, the cosmos would be 10,000 billion times richer than the richest tycoon. This number has to humble us.

The size of the observable universe is 1023 kilometers (the distance from Seattle to Miami is about 5 × 103 km), while its age is 12 to 15 billion years. In our corner of our galaxy, the Milky Way, interstellar distances are huge as well. Our nearest neighbor star, Proxima Centauri, is 5 × 1013 km away. Since it is impractical to use numbers with such large exponents, astronomers use light-years to express distances in the universe. In those units, Proxima Centauri is 4 light-years away from us. In other words, we now see this star as it was 4 years ago because it took that long for its light to reach Earth. To get a better idea of what this distance means, our star, the Sun, is only 8 light-minutes away from Earth. The large neighboring galaxy Andromeda is 2 million light-years away. It is so large, about as large as the Milky Way, that it is visible with the naked eye in the constellation of the same name, between Triangulum and Cassiopeia. By peering at the cosmos with our most powerful telescopes, we see the most distant galaxies as they were some 10 billion years ago, since it took about 10 billion years for their light to reach Earth. This means that we will observe them as they are today in 10 billion years from now, if anyone is left to make the observation.

As we consider our solar system, numbers become less impressive. Only nine planets orbit the Sun and humans have sent spacecraft to eight of them (Pluto has yet to be visited), with actual soft landings on two (Mars and Venus). We now believe that planets are probably common in the universe. In recent years, planets have been discovered in several dozens of nearby star systems. These planets have not yet been observed directly; rather, their presence has been inferred by measuring the wobble that their gravitational pull exerts on their star or by measuring the drop in their star’s brightness as they transit in front of it (literally partially eclipsing it). As for planets that harbor life, we know of only a single one.

Astronomers and cosmologists have calculated an age for the universe, about 12 to 15 billion years. This date of course implies that the universe had a beginning, now universally known as the Big Bang. Thus the universe has not existed for an eternity. Before exploring how the universe got started, however, it would be good to have a feel for what 12 to 15 billion years represent on a scale that we can understand. Carl Sagan cleverly organized this time span into what he called the cosmic calendar. In this calendar the age of the universe is compressed into one single year, starting January 1 and ending December 31 at midnight. Here is an excerpt of this calendar:

| January 1 | Big Bang |

| May 1 | Formation of our galaxy, the Milky Way |

| September 9 | Formation of the solar system |

| September 14 | Formation of Earth |

| September 25 | Origin of life on Earth |

| October 9 | Oldest known bacterial fossils were alive |

| November 12 | First complex eukaryotic cells appeared |

| December 1 | Earth’s atmosphere is fully oxygenated |

| December 16 | First worms |

| December 20 | First land plants |

| December 22 | First amphibians |

| December 24 | First dinosaurs |

| December 29 | First primates |

| December 31 | First humans (at 10:30 p.m.) |

| December 31 | Domestication of fire (at 11:46 p.m.) |

| December 31 | Invention of the alphabet (at 11:59:51 p.m.) |

| December 31 | Roman Empire (at 11:59:56 p.m.) |

| December 31 | Renaissance in Europe (at 11:59:59 p.m.) |

| December 31 | During the last second of the year, five centuries have elapsed and humans have engaged in space exploration. |

It is interesting to note that in the cosmic calendar, it took several months for our Milky Way galaxy to form. We will see in chapter 2 what happened during these “months.” Also, planet Earth formed nine and a half months into the year, but life appeared only two and a half weeks later. This is lightning fast on the cosmic scale. We will see in chapters 4 and 5 what may have happened during that time.

As mentioned, the Big Bang model is rooted in theoretical physics and, in particular, in the convergence of relativity and quantum mechanics. Let us now review these theories to understand how scientists have pieced together an intellectually satisfying account of the birth of the universe.

PHYSICS HOLDS ONE OF THE CLUES TO THE ORIGINS: RELATIVITY

The first quarter of the twentieth century witnessed two great discoveries in physics. In chronological order, they were the realization that mass and energy are equivalent and that matter can be understood both as waves and as particles. The first discovery was made by Albert Einstein (a German, then Swiss, then American citizen) as he was developing the theory of special relativity. The second discovery was made by several scientists who founded quantum mechanics. This new view of matter and energy later allowed cosmologists to put together a comprehensive model for the origin of matter as a direct consequence of the creation of the universe.

Albert Einstein’s famous equation E = mc2 (E is energy, m is mass, and c is the speed of light) derives directly from his and others’ requestioning of the laws of motion that Galileo and Newton formulated centuries ago. This equation shows that mass is a form of energy. It was Einstein who came up with the concept of mass and energy equivalence in his special relativity theory. The term relativity, as used here, deals with the measurement of physical phenomena taking place in frames of reference whose movements are relative to one another, at constant speeds. Frame of reference defines any location in space characterized by a set of coordinates (up, down, left, right, front, and back), while a physical phenomenon is anything that can be measured. For example, you could throw a ball forward (a measurable physical phenomenon) while sitting in a moving bus (one frame of reference) while your friend, standing still on the sidewalk (a second frame of reference), is watching you.1 For you the ball simply moves forward at a certain speed, but for your friend it also moves together with the bus. For her the ball moves faster than for you because the speed (or velocity) of the ball and the speed (or velocity) of the bus add up. If you throw the ball toward the back of the moving bus, the ball moves more slowly for your friend than for you because the velocity of the ball must be subtracted from that of the bus. This is what Galileo and Newton had already described and understood.

Einstein, however, took the position that light behaves differently from anything else that moves. For him the speed of light is the same in all nonaccelerating (that is, moving at constant velocities) frames of reference. In that view, no matter how fast a frame of reference is moving, the speed of light cannot be exceeded. For example, if you flash a laser pointer toward the front of a moving bus, that light, for your motionless friend on the sidewalk, will not move at its own speed (about 300,000 km/sec) plus that of the bus. For both you and your friend, light will move at exactly the same speed, about 300,000 km/sec. The same concept applies to a laser pointing toward the back of the bus. Again, for both you and your friend, light will move at the same speed, not more slowly for her, regardless of the speed of the bus. The constancy of the speed of light has dramatic consequences for physics, as I will next explain.

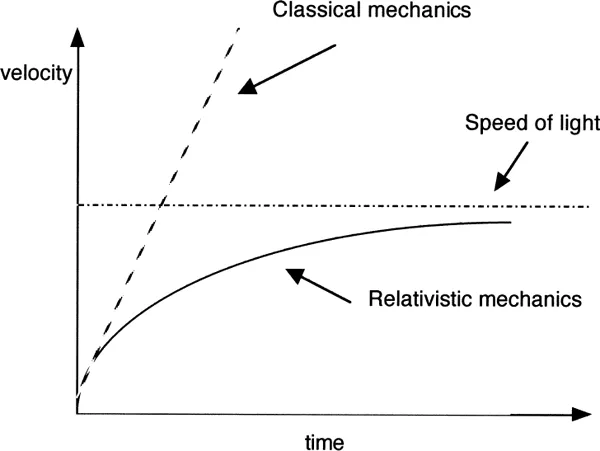

In classical (Newtonian) mechanics, by definition, a constant force acting on an object for an infinite period of time will impart on the object an infinite velocity. For example, an infinitely large fuel tank feeding a rocket engine burning for an infinite time would make a rocket go infinitely fast. Not so in relativistic mechanics; here an infinite velocity is impossible because nothing can go faster than light. Even at an infinite time, during which acceleration is occurring, the object will simply get closer and closer to the speed of light but will never reach it and certainly not exceed it (figure 1.1). This principle is not just a figment of Einstein’s imagination but has been verified experimentally many times. The speed of light in a vacuum is indeed constant, regardless of the velocities of reference frames. (It is, however, not the same in say, air and glass, but the principle of relativity applies under all conditions.)

FIGURE 1.1 A graph of velocity versus time, representing acceleration, in Newtonian mechanics and in relativistic mechanics. Relativistic and Newtonian mechanics predict the same values for acceleration at low velocities. At high velocities, relativistic mechanics predicts smaller and smaller values for acceleration, contrary to Newtonian mechanics.

Next, Einstein realized that time and space are intimately linked and that time is a fourth coordinate, adding to the familiar three dimensions of regular space. Thus in relativity, one speaks of space-time. We know that moving objects move because over time we do not see them exactly in the same position as before. But the speed of light is an intrinsic part of this process because our measurements imply that light moves from the objects to our eyes. Thus space-time becomes a relative quantity (just as positioning in space alone is) that differs in different frames of reference. This complicated reasoning led to the seemingly absurd conclusion of time dilation. According to Einstein’s calculations, a clock (the time-measuring device) in a moving frame of reference runs slower than a clock inside a motionless frame of reference. And this is exactly what happens! Time dilation has been measured by very accurate atomic clocks installed aboard artificial satellites and fast-moving airplanes. This effect is normally observable only at very high speeds because the equations contain a divisor proportional to the square of the speed of light, a very large quantity. Thus our everyday experiences preclude us from feeling time dilation because most of us do not move at speeds that exceed about 0.3 km/sec (about the speed of a jet), whereas the speed of light is 1 million times faster (see appendix 1).

Now, since space-time is relative (as time measurements show), what about mass? In Newtonian mechanics, mass is a constant that does not depend on the speed of the object possessing the mass. Going back to figure 1.1, we see that in relativistic mechanics, a constant force applied over time to an object will result in smaller and smaller velocity increments experienced by the object. Close to the speed of light, these increments become infinitely small. In Newtonian mechanics a body’s rate of change of velocity with time remains constant, which means that acceleration remains constant over time. However, in relativistic mechanics the velocity rate of change, the acceleration of a body, decreases with time and tends toward zero at infinite time. The body is thus seen as resisting acceleration.

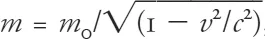

The ability of an object to resist velocity changes is called inertia. Mass, however, is a measure of inertia. For example, a massive rock requires a larger effort to move than a small rock because its inertia, its mass, is greater. Thus in special relativity, the mass of an object increases as its velocity increases, and it tends toward infinity as velocity approaches the speed of light, therefore precluding any object from reaching that speed! The speed of light cannot be reached because at that speed, the mass of the object would be infinite and the force needed to continue to move it also infinite. In special relativity the mass of an object is represented by

, where

m0 is the rest mass (the mass of the object when it is not moving),

v is the object’s velocity, and

c is the speed of light. As can be seen, the quantity

v2/

c2 appears in the equation, meaning that relativistic effects are negligible at low velocity but become important as

v approaches

c. Also, the equation shows that if

v =

c, the divisor equals zero and...