eBook - ePub

Underground U.S.A.

Filmmaking Beyond the Hollywood Canon

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Underground U.S.A.

Filmmaking Beyond the Hollywood Canon

About this book

Whether defined by the carnivalesque excesses of Troma studios (The Toxic Avenger), the arthouse erotica of Radley Metzger and Doris Wishman, or the narrative experimentations of Abel Ferrara, Melvin Van Peebles, Jack Smith, or Harmony Korine, underground cinema has achieved an important position within American film culture. Often defined as "cult" and "exploitation" or "alternative" and "independent," the American underground retains separate strategies of production and exhibition from the cinematic mainstream, while its sexual and cinematic representations differ from the traditionally conservative structures of the Hollywood system. Underground U.S.A. offers a fascinating overview of this area of maverick moviemaking by considering the links between the experimental and exploitative traditions of the American underground.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Underground U.S.A. by Xavier Mendik,Steven Jay Schneider, Xavier Mendik, Steven Jay Schneider in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Film & VideoCHAPTER ONE

‘NO WORSE THAN YOU WERE BEFORE’: THEORY, ECONOMY AND POWER IN ABEL FERRARA’S ‘THE ADDICTION’

Abel Ferrara occupies an unusual niche within the American underground. Although the edge of his work has continually appealed to downtown underground audiences (he is something of a hero at San Francisco’s Roxy Theater, for example) he has also garnered more mainstream acceptance than the other underground filmmakers to whom he is frequently compared in the alternative press (Nick Zedd, Amos Poe et al.). For this reason, his work – or at least its reception – highlights many of the tensions surrounding the dividing line between avant-garde, underground film and the cinema derisively labelled ‘indiewood’ by downtown cinema fans.

The Addiction (1995) stands as something of an interesting anomaly in Ferrara’s oeuvre. A vampire film peppered with references to Nietzsche, Beckett, the My Lai massacre and Burroughs, the film seemed tailor-made to appeal to both an underground and a mainstream audience. But, as Xavier Mendik points out:

Mainstream critical reaction to The Addiction was at best mixed. Although writers such as Gavin Smith [Sight and Sound] praised the complex nature of the film’s construction and style, the narrative’s continual shift from scenes of excess ‘necking’ to narrations on Nietzsche frequently lead to claims that it was both pretentious and greatly distilled its reading of European philosophy.1

While the much tamer Wolf (Mike Nichols, 1994) was praised in the mainstream press for its implicit critique of corporate downsizing and capitalist greed, The Addiction’s explicit retooling of vampirism as another example of Burroughs’ junk pyramid did not elicit the critical commentary it deserved.

The film that should have cemented Ferrara’s status with both mainstream ‘independent’ and underground audiences, then, had the reverse effect of solidifying his status as a primarily underground director. The very things that made The Addiction a difficult viewing experience for mainstream critics endeared it to underground audiences. As Tom Charity notes:

This is one wild, weird, wired movie, the kind that really shouldn’t be seen before midnight.… Shot in b/w, with an effectively murky jungle/funk/rap score, this is the vampire movie we’ve been waiting for: a reactionary urban-horror flick that truly has the ailing pulse of the time. AIDS and drug addiction are points of reference, but they’re symptoms, not the cause.… Scary, funny, magnificently risible, this could be the most pretentious B-movie ever – and I mean that as a compliment.2

In this essay, I plan to discuss the significance of The Addiction’s success as an underground film and to analyse the way it retools vampirism as addiction, economy and power. As the subtitle indicates, I am particularly interested in the way the film uses theory to get its point across. Because of its ‘narrations on Nietzsche’, The Addiction belongs to a growing body of underground work which I have described elsewhere as ‘theoretical fictions’, the kind of fiction in which ‘theory becomes an intrinsic part of the “plot”, a mover and shaker in the fictional universe created by the author’.3

It is the prominent position of theory in The Addiction which made reviewers on opposing sides of the cultural divide label the film as ‘pretentious’ (a word that took on both derisive and celebratory nuances, depending on the user’s cultural point of reference). It is the prominent position within the film of a theoretical discourse that intellectuals critiqued (for greatly distilling a reading of European philosophy) which problematises some of the assumptions that academics tend to make about the cultural uses of theory itself. Like Charity, I think this is ‘one wild, weird, wired movie,’ the vampire movie underground audiences have been waiting for. I hope in this article to demonstrate why.

THE TROPE OF ADDICTION

The film begins with a philosophy lecture on the My Lai massacre – a series of atrocity slides with a voiceover explaining when the attack occurred, what happened in that place and the nature of US national reaction to the horror. As Kathleen (Lili Taylor) and her friend Jean (Edie Falco) leave the lecture, they discuss the central moral problem which the My Lai trial of Lt. Calley seems to illustrate. That is: how can you hold one man responsible for the crimes and guilt of an entire nation, and how do you separate what happened at My Lai from what happened during the rest of the Vietnam War? ‘What do you want me to say?’ Jean asks Kathleen. ‘The system’s not perfect.’ As Kathleen leaves her friend, she encounters a woman dressed in an evening gown (‘Casanova’, played by Annabella Sciorra), a real vamp who drags her into a subway station and bites her neck.

There is a certain grim logic in going from one kind of bloodlust (war crimes) to another (vampirism) here. And there is a way in which the hunger for blood – in all its manifestations – is disturbingly figured in the film as addiction. Throughout the movie, Kathleen keeps returning to images of atrocity – an exhibition of Holocaust photographs, documentary footage of a massacre on the evening news. In part, this continual return serves to remind us of the ethical questions posed at the beginning of the film. Who exactly is responsible for this constant replay of inhumane violence and brutality? To what extent are we all complicit in a world system which seems to need blood as much as vampires do? But, as the last question suggests, Kathleen’s continual return to a kind of ‘primal scene’ of historic atrocity also serves to link war crimes – crimes against humanity – to a trope of physical dependency and sickness, vampirism. ‘Our addiction is evil,’ Kathleen says at one point, meaning that our addiction is to evil, as well as being evil in and of itself. ‘The propensity for this evil lies in our weakness before it,’ she continues. ‘You reach a point where you are forced to face your own needs and the fact that you can’t terminate the situation settles on you with full force.’

If war crimes are linked to vampirism and addiction, blood itself is continually linked to junk. This is most clearly manifest in Kathleen’s emerging vampiric ‘hunger’, as the need for a ‘fix’ makes her physically ill and as the lines between the substances of blood and narcotics are continually blurred. Kathleen’s first ‘fix’ is literally that – a fix. Walking down the street, she sees a junkie with a needle still in his arm. She draws blood up into the syringe, and once home shoots this blood-drug mix into her vein. Later, she initiates her graduate advisor into vampirism by seducing him first with drugs. Inviting him to her apartment, she kisses him and then disappears into the kitchen to fix ‘drinks’. What she brings out, however, is a tray with two syringes, a candle and a spoon. ‘Dependency is a wonderful thing,’ she tells him. ‘It does more for the soul than any formulation of doctoral material. Indulge me.’ It is only later, after he has succumbed to one potentially addictive substance, that she takes a bite out of his neck and turns him into a vampire. And Peina (Christopher Walken), the vampire ‘guide’ Kathleen encounters in the street, continually conflates the language of blood with that of drugs. He mixes terms like ‘fasting’ with ‘shooting up’ to describe his attempts to control ‘the hunger’, and pointedly asks Kathleen if she has read William S. Burroughs’ Naked Lunch.

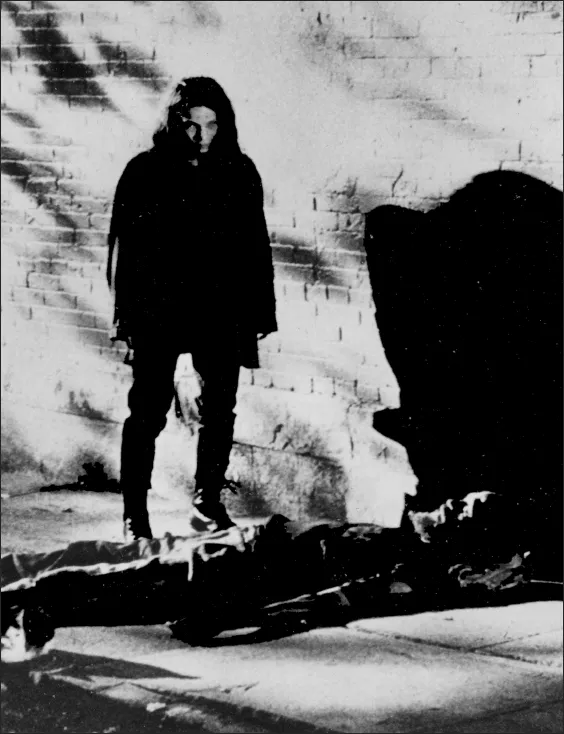

FIGURE 3 Kathleen gets a fix in The Addiction

The repeated commingling of blood and junk, as well as the direct reference to Naked Lunch, invites the viewer to ‘read’ vampirism in The Addiction as yet another example of Burroughs’ ‘Algebra of Need’. In the Preface to Naked Lunch, Burroughs draws a picture of what he terms the ‘junk pyramid’, in which the traffic in heroin – and here, blood – becomes the distilled model of the entire capitalist system. The idea is to ‘hook’ the consumer on a product that s/he does not initially need, in the secure knowledge that once hooked the buyer will return for ever-increasing doses. Burroughs writes:

I have seen the exact manner in which the junk virus operates through fifteen years of addiction. The pyramid of junk, one level eating the level below (it is no accident that junk higher-ups are always fat and the addict in the street is always thin) right up to the top or tops since there are many junk pyramids feeding on the peoples of the world and all built on the basic principles of monopoly: 1) Never give anything away for nothing; 2) Never give more than you have to give (always catch the buyer hungry and always make him wait); 3) Always take everything back if you possibly can. The Pusher always gets it all back. The addict needs more and more junk to maintain a human form… buy off the Monkey.4

The analogy which Burroughs draws between addiction, capitalism, evil and power in Naked Lunch is drawn in The Addiction as well. Like many US urban universities, the university which Kathleen and Jean attend is located in the heart of what we euphemistically call the ‘inner city’ (the film was shot in and around New York University’s Washington Square, before it was ‘cleaned up’). An enclave of privilege, it is surrounded by streets that stand – as Robert Siegle points out – ‘as one of the most potent demystifiers of the illusions in which most of us live’.5 The economy here is based, it seems, on junk. The first time we see Kathleen walk down the street, young men approach her, hoping she will buy, and ‘I want to get high, so high’ plays on the soundtrack. It is in these mean streets that Kathleen is first accosted and then turned into a vampire, and it is to this neighbourhood – as well as to the University itself – that she continually returns, looking for blood.

The geographic construction of Ferrara’s New York is a junk pyramid, then, with the higher-up ‘pushers’ – those who push knowledge and a certain ideology – living off the addicts in the street. In case we do not get the economic/class point, Ferrara includes a doctoral dissertation defence party that plays like some vampiric reworking of May 1968, where the working class and student hordes rise up to attack the power elite. After successfully defending her doctoral thesis, Kathleen invites the faculty to a small gathering at her home. There, the loose coalition of vampire students, street people and one ‘re-formed’ graduate advisor, stage a blood bath – as they gorge themselves on professors and ‘unturned’ students. The class barriers between the University and the streets break down as soon as the underclass unmasks itself at Kathleen’s party, and begins drawing blood.

The subsequent vampire banquet is both a revolt and a final levelling of class structure. ‘The face of “evil”,’ Burroughs writes, ‘is the face of total need.’6 One of the disturbing things about this film is its insistence that reducing everyone to the ‘total need’ level of the addict on the street is a necessary precursor to meaningful sociopolitical, economic change. As Peina darkly tells Kathleen, the first step toward finding out what we really are is to learn ‘what Hunger is.’

THE WILL TO POWER

If blood/junk ‘is the mould of monopoly and possession’, as Burroughs asserts in Naked Lunch,7 it is also – as Allen Ginsberg testified at the Naked Lunch trial – ‘a model for… addiction to power or addiction to controlling other people by having power over them.’8 In The Addiction, Ferrara makes this explicit by substituting tropes of domination for the traditional vampiric trope of seduction. ‘It makes no difference what I do, whether I draw blood or not,’ Kathleen thinks as she gets ready for a vamp-date with her thesis advisor. ‘It’s the violence of my will against theirs.’ The fascistic nature of vampirism is hammered home early in the film with the pointed use of a sound bridge. In a key scene shortly after she has been bitten, Kathleen goes to an exhibit of Holocaust photographs at the University Museum with her friend Jean. A speech by Hitler plays in the background. In the next shot, Kathleen is slumped on the floor of her apartment – in a posture we have come to associate with her vampiric sickness. We still hear Hitler’s voice, echoing now, it seems, in her head. In the next shot, she is on the street, looking for blood.

While vampirism is cinematically linked to a Nietzschean ‘will to power’, the vampiric attack itself is figured as existential drama. Most vampiric encounters in The Addiction begin with a pointed invocation of individual responsibility. ‘Look at me and tell me to go away,’ the vampire tells the victim. ‘Don’t ask, tell me.’ And when the victim – overcome and traumatised by the violence of the unexpected attack – asks the vampire to leave her (usually her) alone, the vampire is quick to assign blame. ‘What the hell were you thinking?’ Kathleen asks an anthropology student. ‘Why didn’t you tell me to get lost like you really meant it?’ When Kathleen herself is first bitten by Casanova, she is called a ‘fucking coward’ and ‘collaborator’.

The question of who bears responsibility for the vampiric attack mirrors the ethical questions surrounding the prosecution of Lt. Calley, raised in the opening scenes of the film. Only here it is not the entire nation that stands culpable for war crimes, but the victim herself – the ‘fucking coward’, the ‘collaborator’ – who is somehow responsible for her own victimisation. The fact that so many of these victims are women and that they are seemingly punished for being too polite, too nice, too passive, only adds to the discomfort that many viewers experience watching a movie which – in the words of J. Hoberman – ‘insists on blaming the victim.’9

Furthermore, there are the recurring shots of atrocity photos within the film itself – shots of the My Lai massacre, the Holocaust, Bosnia – which only serve to increase the ethical stakes of raising the responsibility question at all. Are these victims, too, responsible for what happened to them? Were they too nice, too passive in the face of American/German/Serb aggression? In the face of such horrific brutality, does it even make sense to ask who is responsible, who holds the moral high ground?

Yet the film consistently does invite us to ask the question. The ongoing philosophical quarrel in the film – raised repeatedly by different characters – is the old quarrel between determinism and existentialism, the old dilemma governing the kind of guilt we choose to embrace. Are we evil because of the evil we do, or do we do evil because we are, in the last analysis, evil? In the universe of the film, the constant presence of evil is the only issue on which all Western philosophers seem to agree. Before biting Jean, for example, Kathleen pointedly sets an impossible philosophical task: ‘Prove there’s no evil and you can go.’

What made so many critics and reviewers uncomfortable about watching this film, then, is precisely what was supposed to make them feel uncomfortable. The Addiction mounts what Avital Ronell has called a ‘narcoanalysis’ of society, that is, a mode of analysis in which ‘substance abuse’ and ‘addiction’ name ‘the structure that is philosophically and metaphysically at the basis of our culture.’10 ‘Addiction,’ Ronell writes, ‘has everything to do with the bad conscience of our era.’11 To get the point of Ferrara’s film, one need only add ‘vampirism’ to ‘addiction’ in the above quote.

THE STATUS OF THEOR...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Notes on Contributors

- Foreword: I.A.: I-Won't-Suck-The-Mainstream Art

- Introduction: Explorations Underground: American Film (Ad)ventures Beneath the Hollywood Radar

- Chapter 1. 'No Worse Than You Were Before': Theory, Economy and Power in Abel Ferrara's 'The Addiction'

- Chapter 2. Radley Metzger'S 'Elegant Arousal': Taste, Aesthetic Distinction and Sexploitation

- Chapter 3. Curtis Harrington and the Underground Roots of the Modern Horror Film

- Chapter 4. 'Special Effects' in the Cutting Room

- Chapter 5. Real(IST) Horror: From Execution Videos to Snuff Films

- Chapter 6. A Report on Bruce Conner's 'Report'

- Chapter 7. Voyeurism, Sadism and Transgression: Screen Notes and Observations on Warhol's 'Blow Job' and 'I, A Man'

- Chapter 8. 'You Bled My Mother, You Bled My Father, But You Won't Bleed Me': The Underground Trio of Melvin Van Peebles

- Chapter 9. Doris Wishman Meets the Avant-Garde

- Chapter 10. Full Throttle on the Highway to Hell: Mavericks, Machismo and Mayhem in the American Biker Movie

- Chapter 11. The Ideal Cinema of Harry Smith

- Chapter 12. What is the Neo-Underground and What Isn't: A First Consideration of Harmony Korine

- Chapter 13. Underground America 1999

- Chapter 14. Phantom Menace: Killer Fans, Consumer Activism and Digital Filmmakers

- Chapter 15. Film Co-Ops: Old Soldiers from the Sixties Still Standing in Battle Against Hollywood Commercialism

- Chapter 16. 'Gouts of Blood': The Colourful Underground Universe of Herschell Gordon Lewis

- Chapter 17. Theory of Xenomorphosis

- Chapter 18. Visions of New York: Films from the 1960s Underground

- Chapter 19. A Tasteless Art: Waters, Kaufman and the Pursuit of 'Pure' Gross-Out

- Notes

- Index

- Series List