![]()

1

The Nature of the Problem

A NEW GLOBAL SYSTEM

The issue of sustainability has emerged from problems that have become apparent on a global scale; some are new material configurations and others have emerged as phenomenal now that there are the tools to address them. The view of our planet in its entirety from space has dealt a death blow to flat Earth societies. The British Broadcasting Company had the wit to have a dignitary of a British flat Earth society on its panel of experts commenting on the live coverage of the first Apollo moonshot. It appeared disconcerting to that dignitary, but he was spirited in the explanations and reservations he expressed. Far more important was the effect of the moonshot on everyone who saw it at the time. It was a very moving image: Here we are, all alone, but at least we are alone all together. The image of an earthrise from the Moon is now part of popular culture, a wallpaper motif for a teenager’s bedroom (fig. 1.1). The effect of that image and others like it on the global community has been enormous.

At the time of the first moonshot Allen was in Nigeria and saw a local artist’s tie-dyed images of the Apollo lander, depicted as the same size as the Moon. On a spindly staircase an astronaut, the size of the Man in the Moon, descended to the Moon’s surface, looking back at Earth. A view of Earth from space makes a more powerful statement than anything coming from the writings of environmental professionals. Without it, one might suspect that Earth Day would never have never been the event that it was, and Rachel Carson and her Silent Spring would be of only academic interest, instead of Carson herself being an iconic figure. Allen recently asked his ecology students to raise their hands if they had heard of Marston Bates; nobody moved, but half the class knew of Rachel Carson. Carson and Bates wrote in a very similar vein, but Bates wrote before the space program whereas Carson wrote during it. The moonshot showed us that Earth is our one shot, and that is it.

FIGURE 1.1

The Apollo photograph of the earthrise.

Photograph by NASA.

Our new ethic recognizes physical limits much more explicitly. The system it replaces, that of the Industrial Revolution, was buoyant in its confidence that the application of more power would solve any problem. When Allen first started using a word processor to keep in touch with his family, his father, Frank Allen, wrote back, revealing himself as a child of the Industrial Revolution. He congratulated his expatriate son on his new communication device, saying it was a fine “engine.” In German, the words for “electric motor” and “electronics” translate into English as strong current and weak current, respectively. Frank Allen apparently made no such distinction, for all machines were engines to him. Problems in the industrial age started at a modest size (fig. 1.2) and were attacked with the application of more size and more power. Industrial optimism, the notion that all important limits could be overcome, gave way to a greater realism. That more sober view recognizes that humans cannot predict the consequences of action on the global scale, at which modern problems reside.

Sustainability was not an issue in the nineteenth century, for in an expanding sphere of influence, Man was master of his destiny. There are still many holdovers of that view. A man of vision recently lost to us was Carl Sagan, the popularizer of physical science and a very good atmospheric physicist. Television tributes to him noted that his inspiration to become a scientist was the 1939 World’s Fair. Sagan’s vision is not ours. The 1939 World’s Fair was the hurrah of the industrial age. We see satellites orbiting Earth as crucial for modern problem solving, and they will continue to influence our lives, but “To boldly go where no man has gone before” is nothing that matters. Bigger spaceships going greater distances is the Industrial Revolution model of bigger machines applying more power to overcome human problems of larger scale. But space travel is not just a matter of building a bigger iron bridge across a wider Victorian estuary. The notion of space travel as a way to relieve human crowding on this planet comes from the naiveté of the industrial age. Planetary limits, something the Victorians never encountered, now press issues of sustainability into the public consciousness and onto the agenda for environmental scientists.

The industrial model for our planet, though clearly outmoded, is remarkably persistent. Environmental scientist and conservationist Hugh Iltis, the plant systematist who discovered perennial corn, informed an economist colleague that the nearest star was three and a half light years away. Somehow, a mere three and a half years seemed to reassure the economist as to the viability of space colonization. At 50,000 miles per hour, it would take more than a million years to get there. There is no prospect of colonizing other solar systems. There is nothing to be done about the hole in the ozone layer except to stop making chlorofluorocarbons and wait a century. If we can do nothing active to repair the hole in our own atmosphere, then other celestial bodies in our solar system cannot be made habitable by human manipulation of their entire atmospheres. For example, the Moon is too small even to hold an atmosphere, and planets much larger would crush human colonists. Without the surface of whole celestial bodies made Earth-like, colonization of space can have no direct effect on the sustainability of the human population. Sending a few astronauts off the planet cannot ease population pressure. Therefore, as a population, we are stuck on Earth. Our space exploration has had a significant effect on our views of ecological systems, but that is not the same thing as changing important material ecological flows here on Earth by removing human excess.

FIGURE 1.2

Early industrial power: The earliest phase of the Industrial Revolution was modest and used water power. Here a spade mill has two water wheels (one for the bellows and the other for the hammer). The other structure is a reconstructed skutch mill for removing the soft parts of flax plants to make linen. Both buildings were moved to the Ulster Folk Museum for preservation.

Photographs by T. Allen.

Modern technology allows scientists to see problems that are larger in scale than ever before, and that same technology promises solutions to some of those problems. The Victorians were so confident that they could not foresee that their great-grandchildren would be heading into unimaginable problems. For Victorians, things were either too large to consider or small enough to be challenged with the iron technology of industry. Perhaps we are prepared to struggle because we can imagine things that Lyle, Darwin, and Spencer could not. Ecologists and natural resource managers are being asked to address new problems that are of much larger scale than a coal mine that must be connected to a railway or a canal to a distant source of steel (fig. 1.3). Humanity is cognizant of global problems that invite a human-contrived solution. Although we may not be as confident as were the Victorians, modern humanity appears willing to engage an altogether larger set of issues.

Darwinian evolution is the model that has had the greatest influence on both lay and professional scientists’ views of sustainability. Darwin was inspired by Lyle’s geology, which implied a long time line along which biota have changed. So before the twentieth century, scientists were aware of the long-term and wide spatial scale over which some biological and ecological change occurs. Even so, Lyle’s geology and Darwin’s evolution both take so much time to unfold that they are very abstract. Certainly humans could not plan or influence happenings over such a long time. Notice how Darwinian evolution is cast in terms of “survival of the fittest,” a Spencerian phrase, but one Darwin liked and quoted. The fittest are not those that are the most conditioned to play the most vigorously but those that fit the best into their environment. The prevailing paradigm of biology today is directly descended from Darwin’s, and it is one of genotype interacting with a controlling environment to produce a phenotype. In that paradigm, environment is context, and contexts are unchanging. Although earlier observers might have cogitated about civilizations falling in the face of global events (as many people still do), there was never any thought of doing anything about it. Prior conceptions of human sustainability were of things happening to living and human systems, mere actors inside an inexorably large context. For the Victorian scientist, life fits in; it does not generally control its environment. The Victorian era, and the modern holdover views from the industrial age, use the Darwinian model of a huge, unchangeable environment for the individual.

FIGURE 1.3

Industrial transportation. Now barely used for commercial transportation, the Lee Navigation Canal in east London flourished in Victorian times. (A) This granary and mill is typical of the industry that took advantage of canal transportation. (B–D) The scale of Victorian industrial technology remains human and now is viewed with some sentimentality.

Photographs by T. Allen.

Now we see things on a scale between the unimaginable size of Darwinian eons on one end and daily happenings on the other. The issue of sustainability was of no concern in the nineteenth century because there was no thought of running out of resources, and nothing was going to happen to change things much in the imaginable future (fig. 1.4). Now modern humans see the world as threatening change, but change that, through our best efforts, we might either blunt or ride. If our technology lets us see the world whole, then there is some thought that the same technology might allow humans to plan and influence even something as large as changing continents.

The present authors do not see a simple or permanent technological fix for sustainability, but we are not without hope. A technological fix smacks of an Industrial Revolution model. In fact, technology in itself is as much part of the problem as it is a solution. In this we do not refer only to big, smoky industry; we also see all technology as coming at a price, even green technology. The problem of sustainability is as much a matter of understanding social dynamics and human nature as it is an environmental crisis. The enemy we have seen is ourselves, and it is not just our polluting, consumer selves. The very act of solving environmental problems spends resources, and these resources are in themselves responsible for creating some other problem. It is not that we think solving environmental problems is a bad thing to do. But doing so always presents a dilemma at some level of analysis. The issue of sustainability turns on the nature of problem solving itself. So we begin here a strongly self-reflexive journey as we try to solve the larger problem of a society that engages in a self-defeating struggle. Overcoming immediate problems is part of a process that has brought other societies down, and there is no reason to suppose that modern society is involved in a different process. We are not sure that the indications we offer will work, but they are much better than doing what society does now. At worst, doing what we recommend anticipates retrenchment, so that it can be done with greater humanity. At best, we may have a solution that addresses the larger process, taking the self-defeat out of the struggle.

ECONOMICS, SOCIETY, AND ECOLOGY

Sustainability can be approached at several levels of generality. Our treatment hopes to be wide in its coverage. A narrow view of sustainability would stop at sustaining the biogeophysical system—the species, forests, and rivers. Certainly, without a viable biophysical component, wider views of sustainability cannot work. However, sustainability without a social justice component will not work either. Social justice addresses local considerations of individual sacrifice but in support of a larger system that offers real or perceived benefits for the individual. Along with all this, the whole system must be economically viable. Indeed, some instances of social injustice come from an inviable economy that consumes goodwill as it cuts corners or requires more work from citizens to make up the shortfall. Closing the loop, economic inadequacies take a toll on the biogeophysical systems as overcropping or pressing marginal ecological systems into service destroys soil and extirpates species. Across its widest purview, sustainability works with three major areas of discourse (fig. 1.5). At this highest level, there are economic, social justice, and biophysical components, all of which are crucial. Various scholars have considered biogeophysical, social justice, and economic sustainability. Some have even started to explore the interface between two of the three areas, as in the emerging fields of environmental economics (Carpenter, Ludwig, and Brock 1999; Carpenter, Brock, and Hanson 1999) and rural sociology (Wolf and Allen 1995). However, we are aware of nobody who has worked all facets of sustainability together, and certainly not with a general model that applies across a range of societies of different sizes and degrees of complexity.

FIGURE 1.4

A system despoiled. While Wordsworth wandered “lonely as a cloud” through the Lake District of England, he and the other Lakeland poets imagined that they were escaping the worst of the industrial blight on the country. They did not know that acid rain from Manchester was removing fish from the smaller lakes.

Photographs by T. Allen.

COMPREHENDING SUSTAINABILITY

We are accustomed to thinking of achieving sustainability by doing without—by consuming less and paying more for what we do consume. Regrettably, much of our national and international debate is phrased in such terms. The Kyoto agreement on greenhouse gases, for example, has been cast as a conflict between sustainability and growth. Depicted in this way, the actions needed to sustain the climate to which we are accustomed, for example, will always appear unfavorably. The public’s choice is a foregone conclusion. The immediacy of quarterly balance sheets (for businesses), unemployment levels (for politicians and those unemployed), or poverty (for much of the world) commands attention far more readily than the threat that someday things may go quite wrong. Journalists amplify the problem by their tendency to present all policy disputes as combat between opposing champions. Even when nearly all scientists agree on a matter, journalists will always find one who doesn’t (or perhaps not even a scientist), then present the dispute as a contest between arguments of equal merit. This distortion flows inevitably from allowing business and political leaders and journalists to define the terms of sustainability debate as consumption and employment versus sacrifice and unemployment.

We present here a more nuanced approach. We will show that sustainability is an active condition, not a passive consequence of doing less. One must work at being sustainable. It has costs and benefits and takes both knowledge and resources. Certainly our species cannot infinitely increase its consumption, but to concentrate narrowly on that alone is to miss much that is important. We focus in this book on the roles of hierarchy and complexity in sustaining ecological systems, human societies, and problem solving. We argue that being sustainable consists of such key approaches as the following:

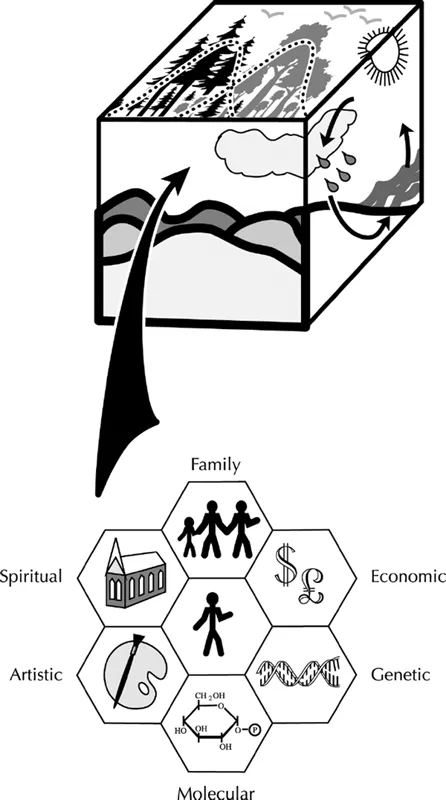

FIGURE 1.5

Humans in the ecological context. Inside the multifaceted ecological system, the humans are not just social creatures; they too are multifaceted, such that describing them in terms of just social justice and economics is a very austere description. In this book we mean to include all the facets of being as part of sustainability.

After Allen and Hoekstra (1994).

• Manage for productive systems rather than for their outputs.

• Manage systems by managing their contexts.

• Identify what dysfunctional systems lack and supply only that.

• Deploy ecological processes to subsidize management efforts, rather than conversely.

• Understand the problem of diminishing returns to problem solving.

We sketch in these pages an understanding of sustainability that is more fundamental than mere exhortations to do such things as use public transportation and take colder showers. Sustainability entails management of systems and their contexts that is intensive and heavily knowledge based. We will achieve sustainability when it becomes a transparent outcome of managing the contexts of production and consumpti...