eBook - ePub

Generalist Practice

A Task-Centered Approach

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Generalist Practice

A Task-Centered Approach

About this book

This essential text presents a "task-centered" methodology—a structured, short-term problem-solving approach—applicable across systems at five levels of practice: the individual, the family, the group, organizations, and communities. The second edition offers more information on systems theories and includes case studies and practice questions with each chapter, as well as checklists for each level of practice and exercises to help students monitor their understanding and skill development.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

INTRODUCTION: TASK-CENTERED AND GENERALIST PRACTICE

The hallmark of generalist practice is the ability to work with multiple systems including the individual, family, small group, organization, and community. The necessity for developing this capacity rests on five observations. First, the difficulties people confront are usually multidetermined. This means that there are multiple causes for problems. For example, a learning disability, a disorganized family, and an inadequate school system might all contribute to the problem of truancy. The effective resolution of the problem would require work with the child, the family, and the school. Second, systems of all sizes experience challenges and turn to social workers for help. Third, people and their social and physical environments are inextricably interconnected and, as a result, social workers must be prepared to work with client systems, their environments, and the interactions between them (Miley, O’Melia, and DuBois 2001). Fourth, it is often more efficient to include work with larger systems when the same problem is experienced by a number of people or families. Fifth, prevention and reform efforts usually require work with multiple systems.

The challenge is to acquire the skills necessary to work effectively with a variety of systems, problems, populations, and settings in a relatively short period of time. This challenge has been accentuated by the Council of Social Work Education (CSWE) which, by means of its acreditation standards, requires a generalist orientation to be taught at the undergraduate level and at the entry level of graduate programs (Sheafor and Landon 1987). We believe that mastering one practice approach, task-centered (TC), that has been applied across systems and with a large array of clients and problems produces competent generalist practitioners. TC has two additional advantages as the core approach for generalist practice. It has been rigorously tested and found effective, and it is an open framework, which means that it can accommodate interventions drawn from other approaches.

1.1.0 THE GENERALIST PERSPECTIVE

A useful description of the generalist worker is as follows: “The generalist social worker [has] the tools to work in various settings with a variety of client groups, addressing a range of personal and social problems and using skills to intervene at practice levels ranging from the individual to the community” (Schatz, Jenkins, and Sheafor 1990:219). Some definitional confusion pertains to the distinction between generalist practice and generic knowledge. Generic knowledge is that which is common to all social workers. For example, all social workers share knowledge about values and human behavior. Although we touch on issues that are part of our generic knowledge base, like values and human development, the topic of this book is generalist practice.

The roots of the generalist perspective have been traced to the inception of social work with the Charity Organization Society (COS) in the late 1800s (Sheafor and Landon 1987). The COS workers, as well as the settlement house workers who followed, were concerned not only with the plight of individuals but with the social conditions that produced those plights. In other words, both groups were concerned about the individual in the environment and the transactions between the two. Others (Schatz, Jenkins, and Sheafor 1990) trace the generalist perspective to the Milford Conferences, which occurred during the 1920s. By that time a number of specialized social services had evolved and the conferences were established to identify the generic elements within social casework. The need to identify generic content for the purpose of establishing a professional identity was made more urgent by the merger of several social work professions into the National Association of Social Workers in 1958.

Although these phenomena and others foreshadowed the development of a generalist orientation, it was not until the seventies that scholarly attempts to develop holistic practice approaches emerged. The first of them was Bartlett’s Common Base of Social Work Practice (1970). Volumes by Meyer (1970), Pincus and Minahan (1973), Goldstein (1973), Siporin (1975), Morales and Sheafor (1977), Germain and Gitterman (1980), and Hartman and Laird (1983) followed. These efforts were particularly notable for developing two themes. One is the common knowledge or skill necessary for a “goal oriented planned change process” (Pincus and Minahan 1973:xiii) across the traditional specializations (casework, group work, and community organization) or the various system levels. A second theme is the relationship between systems and their environments. Both the literature and the movement toward generalist practice continued into the 1980s culminating in the curriculum policy statements of CSWE.

In spite of many efforts, the generalist orientation has not been uniformly defined or developed. In fact, there is disagreement about whether it is a model for practice or a perspective for practice. Sheafor, Horejsi, and Horejsi (2000) define a perspective as a way of viewing or thinking about practice: “The generalist perspective focuses a worker’s attention on the importance of considering … various levels of intervention (51).” A model (or an approach) for practice is, in contrast, a set of procedures that tell the practitioner what to do. Models for practice are specific and often the result of research, whereas perspectives are general and testing their effect is very difficult, if not impossible. In spite of the definitional debate, a number of principles for generalist approaches have been articulated:

1. Incorporation of the generic foundation for social work and use of multilevel problem-solving methodology.

2. A multiple, theoretical orientation, including an ecological systems model that recognizes an interrelatedness of human problems, life situations, and social conditions.

3. A knowledge, value, and skill base that is transferable between and among diverse contexts, locations, and problems.

4. An open assessment unconstricted by any particular theoretical or interventive approach.

5. Selection of strategies or roles for intervention that are made on the basis of the problem, goals, and situation of attention and the size of the systems involved.

(Group for the Study of Generalist and Advanced Generalist, as cited in Schatz, Jenkins, and Sheafor 1990:223)

The relationship between these principles and TC will be described in the following section.

1.2.0 THE TASK-CENTERED APPROACH

TC was developed in the early 1970s by Reid and Epstein (1972). It falls within the category of approaches referred to as “problem solving.” Problem solving, as an approach to social work practice, was first articulated by Helen Harris Perlman (1957). TC has the following characteristics:

1. As noted, it is a problem-solving method of intervention.

2. It is highly structured, which means that the procedures for implementing the model are specific.

3. It focuses on solving problems as clients perceive them.

4. It is time-limited.

5. It is theoretically open and thus can be used with many theoretical orientations.

6. Change occurs through the use of tasks, which are activities designed to ameliorate the identified problems. Tasks can be developed from an array of practice approaches, as well as from problem-solving activities with clients.

7. It is present-oriented.

8. It is an empirical approach to practice in that it (a) was developed from research findings about practice; (b) was constructed with concepts that are researchable; (c) has been tested and found effective; and (d) contains within its procedures activities necessary to evaluate case outcomes.

9. It is appropriate for use with culturally diverse clients, as discussed in chapter 16.

Like the rationale for learning to be a generalist, the rationale for employing TC is based on several factors. First, it is in concert with many of the principles of generalist practice, including its problem-solving focus; openness to multiple theoretical orientations; and procedures that are transferable among a variety of systems, problems, populations, and settings. Second, TC has been tested and found effective with individuals and families. It is one of very few approaches to social work practice that can make this claim. Research findings will be detailed in the following chapters. Third, TC has been applied to work with all systems—individual, family, group, organization, and community. Fourth, it is relatively easy to incorporate interventions from other approaches into the TC framework. Examples of this will be provided in the following chapters. Finally, TC is consistent with the orientation that survey research has found to be most frequently used: “Thus, it appears that action-oriented and task-centered methods are increasingly being used to teach social work practice” (LeCroy and Goodwin 1988:47).

Although TC has many advantages, we are not suggesting it is a magic bullet (were there a magic bullet, social workers would not be needed). Indeed, in some cases, the desired goals will not be reached; in others, no progress may be made at all. Rather, our argument is that, in most cases, TC should be the approach of first choice. The rationale for this position rests on (1) the advantages described in the preceding paragraph; (2) the literature on dropouts; and (3) the relative ease of moving from TC to other approaches, rather than vice versa.

The literature on dropouts indicates that a substantial percentage of clients leave treatment prematurely, that the suspected cause in a number of these cases is the lack of congruence between worker and client with respect to the focus of treatment or target problem, and that the drop-out rate might be lower in time-limited modalities. Since TC mandates congruence on target problems and is time-limited, relying on it as the approach of first choice should enable us to engage more clients whom we might otherwise lose.

With respect to movement away from TC, our experience has been that, when TC has been insufficiently effective, clients are generally amenable to trying other, more complicated, and more time-consuming approaches. We think this occurs because they have experienced for themselves that a parsimonious and straightforward approach is not adequate.

1.3.0 GENERALIST PRACTICE, THE TASK-CENTERED APPROACH, AND THE ECOSYSTEMS PERSPECTIVE

The development of generalist practitioners is obviously a highly desirable goal. The practical problem in accomplishing this goal is that an enormous amount of time would be required if students had to learn a unique approach to practice for each system and each situation. It is our hypothesis that educating students to use TC with systems ranging from the individual to the community will produce competent beginning-level generalists within a reasonable period of time. The openness of both TC and the generalist perspective also provide a sound base for incorporating other theories and intervention procedures as skill levels mature. In addition to the practical problem involved in educating generalist practitioners, there is a conceptual problem. This problem concerns helping practitioners to recognize the possibility and necessity of working with systems other than the most immediate ones—those that present themselves or those to which others refer us. A solution to this problem lies in the ecosystems perspective, which enables us to see people and problems in their environmental contexts and about which a large, robust literature exists. However, since the ecosystems perspective continues to evolve, there is no one description of it on which everyone agrees. Since space limits us here to only a brief description of this perspective, the reader is encouraged to consult additional sources (see, for example, Germain and Gitterman 1996; Kemp, Whittaker, and Tracy 1997; Meyer and Mattaini 1995; and Norlin and Chess 1997).

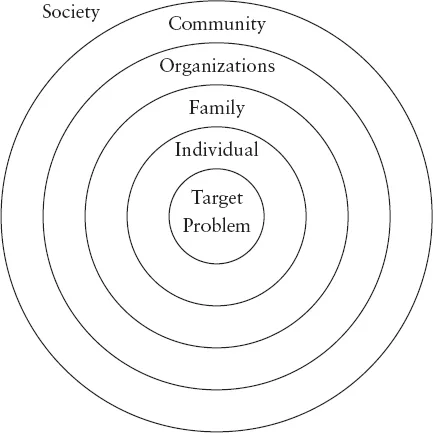

The ecosystems perspective is a collage of two bodies of theory: ecological theory and general systems theory. It is called a “perspective” because it provides a way of thinking about people and their environments rather than offering domain-specific content or a methodology for practice (Meyer 1983; Kemp, Whittaker, and Tracy 1997). Ecological theory has been borrowed from zoology, and the word ecology refers to the relationship between an animal and its environment. The fundamental proposition in this perspective is that human systems and environments are in constant interaction and in a continual process of adaptation and accommodation that is mutually influencing. For our purpose, the most useful concept from this perspective is the ecomap, one version of which is illustrated in Figure 1.1. Other important concepts are habitat (the physical and social environment), niche (the place the system occupies), goodness-of-fit (the extent to which there is a harmony between the system and the environment), stress (result of a misfit), and coping (strategies to ameliorate stress).

Systems theory combines ideas from a number of fields including information theory and biology. Like ecological theory, it stresses the importance of the relationship between people and their environments. For our purposes, its most salient contributions are the definition of a system and the concept of boundaries. A system is defined as a complex of elements that form an organized, interrelated whole. Two of the concepts that capture some of the organization of systems are hierarchy and subsystems. Using a family system as an example, it is apparent that the family members are the elements that, taken together, form the whole or the unit. Boundaries are evident because we can define who is part of the system and who is not. Families exhibit a clear hierarchy, with parents expected to have more power than children. It is also apparent that the work of the family is carried out by subsystems, such as the marital, parental, and sibling subsystems. The division of power and labor and the number of subsystems are more complex in larger systems like organizations. The concept of boundaries is used to examine the amount of information exchanged between systems or subsystems. When boundaries are rigid, little information is exchanged. When they are open, adequate amounts of information are exchanged. When they are porous, too much information is exchanged and one system can be overwhelmed by another. Other useful concepts include steady state and homeostasis (the tendency of systems to maintain a dynamic equilibrium and the mechanisms for doing so) and equiand multifinality (the relationship between means and ends).

The fundamental contribution of an ecosystems perspective to task-centered generalist practice is that it expands our ability to recognize the possibilities and necessity to work with a variety of systems. The ecomap in Figure 1.1 is derived from ecological theory and can be used to analyze human situations within this perspective. Typically, however, the individual, rather than the problem, is nested in the center of the concentric circles. We have placed the problem at the center, because it is the target of change in this approach to practice.

FIGURE 1 Systems and Target Problems

Examination of the various systems within the concentric circles enables us to consider how each contributes to the existence of the problem. The example of a child failing academically has already been used to illustrate this kind of examination. Consider another example: child abuse or neglect.

Individual: the child might be “hard-to-manage.”

Family: the parent(s) might be deficient in resources, problem-solving skills, or impulse control.

Organizat...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Authors and Contributors

- Preface

- 1. Introduction: Task-Centered and Generalist Practice

- Part One: Individuals

- Part Two: Families

- Part Three: Groups

- Part Four: Larger Systems

- Part Five: Diversity and Conclusions

- References

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Generalist Practice by Eleanor Reardon Tolson,William J. Reid,Charles D. Garvin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Research & Methodology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.