![]()

PART 1

BLACK

ROOMS AND RAGE

![]()

CHAPTER 1

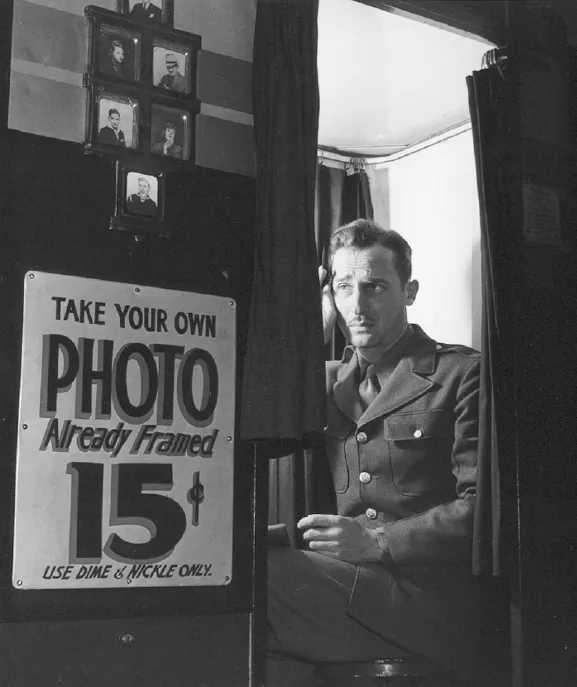

ALREADY FRAMED: ESTHER BUBLEY INVENTS NOIR

ROOMING HOUSES

There comes a moment in many film noirs when the bad girl emerges snarling with anger as she ensnares the dimwitted doomed guy. The appropriately named Ann Savage turns on hapless, guilty Tom Neal in Detour, her face transformed from forlorn innocence after he picks her up hitchhiking into vicious rage when she reveals to him that she recognizes his clothes and car as belonging to another man, the dead one Neal has dumped along the highway. Jane Greer, dressed like a nun, turns on Robert Mitchum in the final moment of Out of the Past after she kills her gangster lover Kirk Douglas, leaving Mitchum dead and framed for a number of murders. So too Barbara Stanwyck in Double Indemnity sneers at Fred McMurray when he starts getting cold feet about their plans to murder her husband. By the time she appears in The File on Thelma Jordan, Stanwyck can turn on her former pimp with such fury she blinds him with a cigarette lighter. Gloria Grahame laughs at Jack Palance when he slaps her face in Sudden Fear, reducing him to her sex toy after she threatens to alert his rich wife, Joan Crawford, that he is already married. Lizabeth Scott in Too Late for Tears reveals her greedy murderous desire for the cash hurled mistakenly into the convertible she and her husband drive. She viciously gets rid of one man after another until she lands in Mexico alone with the money. These scenes repeat themselves again and again as if it is not enough that the women’s morbid sexuality already marks them as bad. They must also mutate into animals. Simone Simon in Cat People literally turns into a seething black leopard stalking her competition, her husband’s assistant, and killing her psychiatrist after he kisses her. This early noir horror film sets the image of sexual allure as animality. Because it is literalized, we never see Simone Simon’s face transform; it is her body, which is never actually seen either. Instead, we hear the rustle of her paws amid the leaves, see the shadow of her form, discover the slashes of her claws. Good girl “Kansas” in Phantom Lady dresses up as a femme fatale to get drummer Elisha Cook Jr. to admit to seeing the elusive woman in the hat accompanying her boss. When she goes with him to the after hours jam session, she lures him with her orgasmic responses to his drum solo. The image of the woman turning into wild beast is a code for the impossible: to see the moment of female orgasm. Its terrifying ability to alter the woman’s face is perhaps what these moments of vituperation are really about. Rather than the laugh of the Medusa, we see her fury at men’s irrelevance.

This view of triumphant female rage—refusing to look pleasing, to be the soothing and demure helpmate—inevitably results in death. Both she and the man are doomed, but for a tiny instant her desire and its expression have trumped social conventions about femininity. We watch Jean Wallace in Joseph H. Lewis’s The Big Combo as her lover Richard Conte slowly goes down on her. The camera remains focused on her face as it fractures following her orgasm. By this time when the genre had entered its baroque period, with films as different as Robert Aldrich’s Kiss Me Deadly (1955) or Samuel Fuller’s The Naked Kiss (1963), the moments of female rage—when Lily Carver points her gun at Ralph Meeker’s Mike Hammer and begs “Kiss me, Mike” or when Kelly grabs the phone receiver and beats Grant to death after she discovers his pedophilia, repeating and mirroring the first scene where she beats her pimp with a leather handbag—had entered the realm of domestic sit-com camp. During the mid-1940s, however, these scenes still had the air of tragedy clinging to them because they revealed anxieties circulating within the culture about women’s wartime mobility and participation in heavy industry. Women’s seething rage could burst forth without logical antecedent; it’s somewhat confusing to the man why the femme fatale explodes at the moment she does. The plot motivation is never quite enough to account for it; only her unpredictable and invisible sexuality explains it. A mystery to the ordinary men attracted to these women, it is always transparent to the women who meet them; yet, knowing who they are, the women rarely condemn their demonic sisters. As Gloria Grahame insists in The Big Heat, “We’re sisters under our minks.”

This dangerous autonomy, visualized in the snarl that comes invariably at the moment when the female takes control of the man and the situation, indexes the changing position of women accelerated by the Second World War. Women had experienced a different kind of mobilization during the 1940s when many left poorly paying jobs as domestics or clerks in search of more lucrative employment in factories and in federal government offices. Many of these women ended up living in rooming houses full of other single women with whom they shared meals and chores and movie dates. Marjory Collins’s April 1943 shot of women massing a downtown block for an evening movie documents a female takeover of urban space, one that Giuliana Bruno revealed had occurred in Italy during the rise of fascism and throughout the war.1 Crowds of “Thursday night shoppers [stand] in a line outside a movie theatre” in Baltimore, Maryland, as neon flashes above them a huge exclamatory: NEW.2 Louis Faurer’s photograph of working women waiting for a bus on Broadway before a poster advertising a Barbara Stanwyck movie (clearly misdated as 1948, because the movie is the 1950 film No Man of Her Own) details how women could move through the city at night dressed much like the actress (in that film she assumes the identity of a dead woman she befriended on the train to San Francisco just before it wrecks). In 1948, the Kinsey Report had opened up discussions of Americans’ sex lives. As Andrea Fisher observes in her ground-breaking look at the women photographers working in the FSA/OWI, “[T]hese images from the 1940s … cast suspicion on their promise of a visual presence, their fascinations turn on an offering of sexuality.”3 That offering could be had, in part, because women could live alone, occupying single rooms. If the film noir femme fatale rarely possessed this kind of domestic isolation—she’s usually a kept woman—her snarl set her apart from proper domesticity. She didn’t need to work a job, like the women flocking to war work, but she was their sister nevertheless.

Photographer Esther Bubley was among the last members of the extraordinary crew of artists hired by Roy Stryker to document government programs aimed at ameliorating poverty during the Depression and, when the nation entered World War II, to record the efforts undertaken by citizens to support national defense. Hired as a negative cutter, Bubley stayed on after the Farm Security Administration had become the Office of War Information. Her large body of work focused on these uprooted working women. Bubley tracked the private lives of young women, such as her sister Enid, who lived in boarding houses or in a series of furnished apartments, as Esther and her other sister, Claire, did, while they worked government jobs. Her many photographs, intimate moments of privacy—daydreaming out a window, napping on a couch, thumbing a magazine, arranging personal objects on a dresser—offer a sense of stasis, of lives held in abeyance waiting alone for an uncertain future. In her most famous image, captioned, “Girl sitting alone in the Sea Grill, a bar and restaurant, waiting for a pickup,” Bubley anticipated the signature icons surrounding the femme fatale: a lone woman sits at the end of long booth, a glass of beer almost empty, smoking, framed by Venetian blinds. Behind them the night is black save for the neon letters above her; but a man’s head is visible outside the window behind her, peering at her back. She waits under surveillance, explaining: “I come in here pretty often, sometimes alone, mostly with another girl, we drink beer, and talk, and of course we keep our eyes open you’d be surprised at how often nice, lonesome, soldiers ask Sue, the waitress to introduce them to us.”4 Like Ella Raines in Phantom Lady, who sits night after night watching bartender Andrew Tombes Jr. until she finally follows him through the dark streets one night aggressively chasing him, not for companionship but for information, Bubley’s girl also “keeps her eyes open” for men. In her impassive availability, she signals her desire; yet hers is a figure in relative repose, arms crossed, not in defiance but resignation. For the young women in the rooming houses and bars of Washington, D.C., in 1943, nightlife is spent usually alone or in the company of other lonely women; they wait, but they are free. The sequence of pictures from the Sea Grill contains some of the most detailed captions written by Bubley. They constitute a pulp narrative about how to pick up soldiers. One image notes a “Girl and a soldier came into the Sea Grill separately, but are developing a beautiful friendship.”5 Another zooms in on “A slightly inebriated couple at the Sea Grill.”6 These women, as Bubley makes clear, are poised in a strange contradiction. Alone and mobile, they are free from family scrutiny and control; yet their availability is limited by the absence of men who have deserted this and other urban spaces for war.

Hints of lesbian desire appear everywhere in Bubley’s images as the women curl up together to read or listen to the radio, but the overriding sense is of a deep malaise. All dressed up and nowhere to go, these women wait—for men. No wonder the films made immediately upon the war’s conclusion feature a new brutal kind of female sexual aggression. Phyllis Dietrichson in Double Indemnity doesn’t just await Walter Neff after he arrives at her bungalow door to sell her an insurance policy. She shows up later at his door, hair coiffed and perfumed in sweater and slacks, asking for a drink. Although she is housed in a tidy bungalow complete with step-daughter, husband, and maid, and the year of the film’s action is 1938—before the war had even started in Europe—thus seeming to have little in common with Bubley’s sisters and their roommates, she too appears poised for something to happen. As does her step-daughter, Lola, whom we find playing Chinese checkers a few nights later with Phyllis when Neff shows up to have Mr. Deitrichson sign the insurance policy, biding her time until she can go downtown to meet her boyfriend, Nino Zachetti. After her father’s death, Lola moves into her own apartment: “Four walls and you just sit and look at them,” as Neff characterizes it. Filmed in 1943, the movie locates these two women—the murderous stepmother and the grieving, alienated daughter—who live out a solitary female existence, dependent upon, yet divorced from, men.

Although the rooming houses Bubley was documenting seemed wholesome enough in 1943, the rooming house remains, in fiction, film, and art, a sinister place filled with wild women and brutal men. Cornell Woolrich’s novel (which became the Stanwyck film No Man of Her Own) I Married a Dead Man tracks Helen Georgesson as “she climbed the rooming-house stairs like a puppet dangling from slack strings. A light bracketed against the wall, drooping upside-down like a withered tulip in its bell-shaped shade of scalloped glass, cast a smoky yellow glow. A carpet-strip ground to the semblance of decayed vegetable-matter, all pattern, all color, long erased, adhered to the middle of the stairs, like a form of pollen or fungus encrustation.”7 This dreary space, home to the rejected, pregnant nineteen-year-old girl becomes an iconic zone of danger and defeat; Gloria Grahame, her face hideously scarred when her gangster lover scalds her with hot coffee, holes up in tough cop Glenn Ford’s room in Fritz Lang’s 1953 film, The Big Heat. In Robert Siodmak’s The Killers, Burt Lancaster (Swede) awaits his murderers in his small dark room with stoic calm; doublecrossed by a woman, he has simply given up the will to live. More recently, the Coen brothers made the hotel where Barton Fink suffered Hollywood writer’s block a central character in their parodic, moody film noir. Ed and Nancy Keinholz’s Pedicord Apt., an installation in the Weisman Art Museum in Minneapolis, reconstructs a seedy 1940s rooming house, letting us enter its claustrophobic hallway and eavesdrop on the domestic melodramas behind each grim door. Just those sorts of doors had been the actual inspiration for one of the greatest works of twentieth-century America fiction. Living in and managing the rundown hotel his family owned, Nathanael West watched its long-term residents who lived out a desperation during the Depression. They became the basis—along with a cache of real letters he was given—for his brilliant dissection of transience, Miss Lonelyhearts.

What distinguishes Bubley’s images of the rooming-house young women from Helen Georgesson or Miss Lonelyhearts, for that matter, is the way her camera has opened the doors finding behind each rather clean, well-lighted spaces often cluttered with friends, magazines, pictures from home, and drying ...